The Pol Β Variant Containing Exon Α Is Deficient in DNA Polymerase But

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

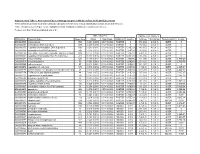

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

HSP90 Regulates DNA Repair Via the Interaction Between XRCC1 and DNA Polymerase &Beta

ARTICLE Received 30 Oct 2013 | Accepted 7 Oct 2014 | Published 26 Nov 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms6513 HSP90 regulates DNA repair via the interaction between XRCC1 and DNA polymerase b Qingming Fang1,2,w, Burcu Inanc3, Sandy Schamus2, Xiao-hong Wang2, Leizhen Wei2,4, Ashley R. Brown2, David Svilar1,2, Kelsey F. Sugrue2,w, Eva M. Goellner1,2,w, Xuemei Zeng5, Nathan A. Yates2,5,6, Li Lan2,4, Conchita Vens3,7 & Robert W. Sobol1,2,8,w Cellular DNA repair processes are crucial to maintain genome stability and integrity. In DNA base excision repair, a tight heterodimer complex formed by DNA polymerase b (Polb) and XRCC1 is thought to facilitate repair by recruiting Polb to DNA damage sites. Here we show that disruption of the complex does not impact DNA damage response or DNA repair. Instead, the heterodimer formation is required to prevent ubiquitylation and degradation of Polb. In contrast, the stability of the XRCC1 monomer is protected from CHIP-mediated ubiquitylation by interaction with the binding partner HSP90. In response to cellular pro- liferation and DNA damage, proteasome and HSP90-mediated regulation of Polb and XRCC1 alters the DNA repair complex architecture. We propose that protein stability, mediated by DNA repair protein complex formation, functions as a regulatory mechanism for DNA repair pathway choice in the context of cell cycle progression and genome surveillance. 1 Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA. 2 Hillman Cancer Center, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA. 3 The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Division of Biological Stress Response, Amsterdam 1006BE, The Netherlands. -

DNA Related Enzymes As Molecular Targets for Antiviral and Antitumor- Al Chemotherapy

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] Current Drug Targets, 2018, 19, 000-000 1 REVIEW ARTICLE DNA Related Enzymes as Molecular Targets for Antiviral and Antitumor- al Chemotherapy. A Natural Overview of the Current Perspectives Hugo A. Garro* and Carlos R. Pungitore INTEQUI-CONICET, Fac. Qca., Bioqca. y Fcia., Univ. Nac. de San Luis (U.N.S.L), Chacabuco y Pedernera, 5700 San Luis, Argentina Abstract: Background: The discovery of new chemotherapeutic agents still remains a continuous goal to achieve. DNA polymerases and topoisomerases act in nucleic acids metabolism modulating different processes like replication, mitosis, damage repair, DNA topology and transcription. It has been widely documented that Polymerases serve as molecular targets for antiviral and antitumoral chemotherapy. Furthermore, telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein with exacerbated activity in most of the tumor cell lines, becoming as an emergent target in Cancer treatment. A R T I C L E H I S T O R Y Methods: We undertook an exhaustive search of bibliographic databases for peer-reviewed research literature related to the last decade. The characteristics of screened bibliography describe structure ac- Received: February 05, 2018 Revised: April 17, 2018 tivity relationships and show the principal moieties involved. This work tries to summarize the inves- Accepted: April 19, 2018 tigation about natural and semi-synthetic products with natural origin with the faculty to inhibit key DOI: enzymes that play a crucial role in DNA metabolism. 10.2174/1389450119666180426103558 Results: Eighty-five data references were included in this review, showing natural products widely distributed throughout the plant kingdom and their bioactive properties such as tumor growing inhibi- tory effects, and anti-AIDS activity. -

DNA Polymerase Beta Overexpression Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Esophageal Cancer Patients

Article Preclinical Medicine September 2013 Vol.58 No.26: 32743279 doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5956-2 DNA polymerase beta overexpression correlates with poor prognosis in esophageal cancer patients ZHENG Hong1†, XUE Peng1†, LI Min2, ZHAO JiMin2, DONG ZiMing2* & ZHAO GuoQiang2* 1 Department of Pathophysiology, Medical College of Henan University, Kaifeng 475004, China; 2 School of Basic Medical Sciences, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China Received March 26, 2013; accepted May 17, 2013; published online July 17, 2013 Gene of DNA polymerase beta (pol) plays an important role in base excision repair, DNA replication and translesion synthesis. This study aims to investigate the expression and prognostic significance of DNA pol in esophageal cancer. DNA pol expres- sion was analyzed using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and immunohistochemical staining on tissue samples from a consecutive series of 114 esophageal squamous carcinoma patients who underwent resections between 2002 and 2006. Pol ex- pression was investigated on its correlation to clinico-pathological factors and survival. RT-qPCR results showed higher expres- sion of DNA pol mRNA in tumor tissue than in its matched adjacent non-tumor tissue sample, different expression of DNA pol mRNA was noticed with significance between tumors with and without lymph node metastasis. Immunohistochemistry staining results indicated the pol strong-positive rate was 44.73% (51/114) in tumor tissue samples and 0.00% in matched adjacent non-tumor tissue samples, with significant difference. Kaplan-Meier survival curves revealed that high expression of pol was associated with tumor metastasis and poor prognosis in esophageal cancer patients. Our data suggests that pol plays an important role in tumor progression and that high pol expression predicts an unfavorable prognosis in esophageal squamous carcinoma patients. -

Mitochondrial DNA Replication in Mammalian Cells: Overview of the Pathway

Essays in Biochemistry (2018) 62 287–296 https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20170100 Review Article Mitochondrial DNA replication in mammalian cells: overview of the pathway Maria Falkenberg Department of Medical Biochemistry and Cell Biology, University of Gothenburg, P.O. Box 440, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden Correspondence: Maria Falkenberg ([email protected]) Downloaded from http://portlandpress.com/essaysbiochem/article-pdf/62/3/287/486690/ebc-2017-0100c.pdf by guest on 05 October 2020 Mammalian mitochondria contain multiple copies of a circular, double-stranded DNA genome and a dedicated DNA replication machinery is required for its maintenance. Many disease-causing mutations affect mitochondrial replication factors and a detailed under- standing of the replication process may help to explain the pathogenic mechanisms under- lying a number of mitochondrial diseases. We here give a brief overview of DNA replication in mammalian mitochondria, describing our current understanding of this process and some unanswered questions remaining. Introduction MitochondrialDNA (mtDNA) is a double-stranded moleculeof16.6 kb (Figure 1, lower panel). The two strandsofmtDNA differ in their base composition, with one being rich in guanines, making it possible to separate a heavy (H)and a light (L) strand by density centrifugation in alkaline CsCl2 gradients [1]. The mtDNA contains one longer noncoding region (NCR) also referred to as the control region. Inthe NCR, there are promoters for polycistronic transcription, one for each mtDNA strand; the light strand promoter (LSP) and the heavy strand promoter (HSP). The NCRalso harbors the origin for H-strand DNA replication (OH). A second origin for L-strandDNA replication (OL)islocated outsidetheNCR, withinatRNAcluster approximately 11,000 bp downstream of OH. -

Epigenetic Mechanisms Involved in the Cellular Response to DNA Damage Processed by Base Excision Repair

Epigenetic mechanisms involved in the cellular response to DNA damage processed by Base Excision Repair Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Laura Gail Bennett November 2017 i Abstract Chromatin remodelling is required for access to occluded sequences of DNA by proteins involved in important biological processes, including DNA replication and transcription. There is an increasing amount of evidence for chromatin remodelling during DNA repair, although this has been mostly focused towards DNA double strand break and nucleotide excision repair. At this time there is little evidence for chromatin remodelling in base excision repair (BER). BER is a highly conserved DNA repair pathway which processes spontaneous endogenous DNA base damages generated by oxidative metabolism, but also those induced by exogenous agents (eg. ionising radiation), to maintain genome stability. The mechanism in which the BER repairs damaged bases has been extensively studied and the repair proteins involved are well known. However in terms of chromatin, BER is poorly understood. It is thought that chromatin remodelling occurs due to accumulating evidence indicating that certain BER enzymes are significantly less efficient at acting on sterically occluded sites and near the nucleosome dyad axis. At this time the mechanisms and enzymes involved to facilitate BER are unknown. Therefore, the study presented in this thesis aimed to identify specific histone modification enzymes and/or chromatin remodellers that are involved in the processing of DNA base damage during BER. A method to generate two mononucleosome substrates with a site specific synthetic AP site (tetrahydrofuran; THF) was used to measure recombinant AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) activity alone, and APE1 in HeLa whole cell extract (WCE) that contained chromatin modifiers. -

Oxidative Damage to Dna in Alzheimer's Disease

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Chemistry Chemistry 2013 OXIDATIVE DAMAGE TO DNA IN ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE Sony Soman University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Soman, Sony, "OXIDATIVE DAMAGE TO DNA IN ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--Chemistry. 28. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/chemistry_etds/28 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Chemistry at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Chemistry by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

DNA Repair and Mutagenesis in Vertebrate Mitochondria: Evidence for the Asymmetric DNA Strand Inheritance

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/842617; this version posted November 15, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. - 1 - DNA repair and mutagenesis in vertebrate mitochondria: evidence for the asymmetric DNA strand inheritance Bakhyt MATKARIMOV1 and Murat K. SAPARBAEV2,* 1 National laboratory Astana, Nazarbayev University, Astana 010000, Kazakhstan. 2 Groupe «Réparation de l'ADN», Equipe Labellisée par la Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer, CNRS UMR8200, Université Paris-Sud, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, F-94805 Villejuif Cedex, France. *Corresponding author. M.K.S.: phone: +33 1 42115404; Email: [email protected] A variety of endogenous and exogenous factors induce chemical and structural alterations to cellular DNA, as well as errors occurring throughout DNA synthesis. These DNA damages are cytotoxic, miscoding, or both, and are believed to be at the origin of cancer and other age related diseases. A human cell, in addition to nuclear DNA, contains thousands copies of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), a double-stranded, circular molecule of 16,569 bp. It was proposed that mtDNA is a critical target for reactive oxygen species (ROS), by-products of the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), generated in the organelle during aerobic respiration. Indeed, oxidative damage to mtDNA are more extensive and persistent as compared to that of nuclear DNA. Although, transversions are the hallmarks of mutations induced by ROS, paradoxically, the majority of mtDNA mutations that occurred during ageing and cancer are transitions. -

Massively Multitask Networks for Drug Discovery

Massively Multitask Networks for Drug Discovery Bharath Ramsundar*,y, ◦ [email protected] Steven Kearnes*,y [email protected] Patrick Riley◦ [email protected] Dale Webster◦ [email protected] David Konerding◦ [email protected] Vijay Pandey [email protected] (*Equal contribution, yStanford University, ◦Google Inc.) Abstract After a suitable target has been identified, the first step in the drug discovery process is “hit finding.” Given some Massively multitask neural architectures provide druggable target, pharmaceutical companies will screen a learning framework for drug discovery that millions of drug-like compounds in an effort to find a synthesizes information from many distinct bi- few attractive molecules for further optimization. These ological sources. To train these architectures at screens are often automated via robots, but are expensive scale, we gather large amounts of data from pub- to perform. Virtual screening attempts to replace or aug- lic sources to create a dataset of nearly 40 mil- ment the high-throughput screening process by the use of lion measurements across more than 200 bio- computational methods (Shoichet, 2004). Machine learn- logical targets. We investigate several aspects ing methods have frequently been applied to virtual screen- of the multitask framework by performing a se- ing by training supervised classifiers to predict interactions ries of empirical studies and obtain some in- between targets and small molecules. teresting results: (1) massively multitask net- works obtain predictive accuracies significantly There are a variety of challenges that must be overcome better than single-task methods, (2) the pre- to achieve effective virtual screening. Low hit rates in dictive power of multitask networks improves experimental screens (often only 1–2% of screened com- as additional tasks and data are added, (3) the pounds are active against a given target) result in im- total amount of data and the total number of balanced datasets that require special handling for effec- tasks both contribute significantly to multitask tive learning. -

Mutation in DNA Polymerase Beta Causes Spontaneous Chromosomal Instability and Inflammation-Associated Carcinogenesis in Mice

cancers Article Mutation in DNA Polymerase Beta Causes Spontaneous Chromosomal Instability and Inflammation-Associated Carcinogenesis in Mice 1, 1, 1 2 Shengyuan Zhao y, Alex W. Klattenhoff y, Megha Thakur , Manu Sebastian and Dawit Kidane 1,* 1 Division of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Pharmacy, Dell Pediatric Research Institute, The University of Texas at Austin, 1400 Barbara Jordan Blvd. R1800, Austin, TX 78723, USA 2 Department of Epigenetics and Molecular Carcinogenesis, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Science Park, Smithville, TX 78957, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +(512)-495-4720; Fax: +1-512-495-4945 These authors contributed equally. y Received: 14 June 2019; Accepted: 8 August 2019; Published: 13 August 2019 Abstract: DNA polymerase beta (Pol β) is a key enzyme in the base excision repair (BER) pathway. Pol β is mutated in approximately 40% of human tumors in small-scale studies. The 5´-deoxyribose-5-phosphate (dRP) lyase domain of Pol β is responsible for DNA end tailoring to remove the 5’ phosphate group. We previously reported that the dRP lyase activity of Pol β is critical to maintain DNA replication fork stability and prevent cellular transformation. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that the human gastric cancer associated variant of Pol β (L22P) has the ability to promote spontaneous chromosomal instability and carcinogenesis in mice. We constructed a Pol β L22P conditional knock-in mouse model and found that L22P enhances hyperproliferation and DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) in stomach cells. Moreover, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from L22P mice frequently induce abnormal numbers of chromosomes and centrosome amplification, leading to chromosome segregation errors. -

Small‐Molecule Inhibitors of Dna Polymerase Function

SMALL‐MOLECULE INHIBITORS OF DNA POLYMERASE FUNCTION DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des Akademischen Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Tobias Strittmatter aus Küssaberg‐Kadelburg an der Universität Konstanz Mathematisch‐Naturwissenschaftliche Sektion Fachbereich Chemie 2014 Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 05. Dezember 2014 Prüfungsvorsitz: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Müller 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Andreas Marx 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. Thomas U. Mayer Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-274434 „Meinen Eltern” Danksagung Die vorliegende Arbeit entstand in der Zeit von November 2009 bis August 2014 in der Arbeitsgruppe von Prof. Dr. Andreas Marx am Lehrstuhl für Organische und Zelluläre Chemie am Fachbereich Chemie der Universität Konstanz. Nach diesem Zeitraum geprägt von intensiver Forschungsarbeit liegt nun meine Dissertation vor und ein weiteres Kapitel meiner beruflichen Karriere kann nun erfolgreich abgeschlossen werden. Aus diesem Grund ist es jetzt auch an der Zeit, mich bei all denen zu bedanken, die mich während dieser spannenden Zeit begleitet, unterstützt und gefördert haben. Meinem Doktorvater Prof. Dr. Andreas Marx danke ich ganz herzlich für die Überlassung der sehr interessanten und interdisziplinären Themenstellung, sowie für das in mich gesetzte Vertrauen, welches mir viel Raum für die selbstständige Bearbeitung und kreative Gestaltung des Themas erlaubte. Ihm, wie auch den weiteren Mitgliedern meines „Thesis Committee“, Prof. Dr. Thomas Mayer und Herrn Prof. Dr. Michael Berthold, danke ich zudem für die anregenden wissenschaftlichen Diskussionen und die geleisteten Hilfestellungen. Prof. Dr. Thomas Mayer danke ich außerdem für die Übernahme des Zweitgutachtens und Herrn Prof. Dr. Gerhard Müller für die Übernahme des Prüfungsvorsitzes. -

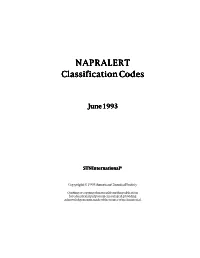

NAPRALERT Classification Codes

NAPRALERT Classification Codes June 1993 STN International® Copyright © 1993 American Chemical Society Quoting or copying of material from this publication for educational purposes is encouraged, providing acknowledgement is made of the source of such material. Classification Codes in NAPRALERT The NAPRALERT File contains classification codes that designate pharmacological activities. The code and a corresponding textual description are searchable in the /CC field. To be comprehensive, both the code and the text should be searched. Either may be posted, but not both. The following tables list the code and the text for the various categories. The first two digits of the code describe the categories. Each table lists the category described by codes. The last table (starting on page 56) lists the Classification Codes alphabetically. The text is followed by the code that also describes the category. General types of pharmacological activities may encompass several different categories of effect. You may want to search several classification codes, depending upon how general or specific you want the retrievals to be. By reading through the list, you may find several categories related to the information of interest to you. For example, if you are looking for information on diabetes, you might want to included both HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC and ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC and their codes in the search profile. Use the EXPAND command to verify search terms. => S HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17006/CC OR ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17007/CC 490 “HYPOGLYCEMIC”/CC 26131 “ACTIVITY”/CC 490 HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC ((“HYPOGLYCEMIC”(S)”ACTIVITY”)/CC) 6 17006/CC 776 “ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC”/CC 26131 “ACTIVITY”/CC 776 ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC ((“ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC”(S)”ACTIVITY”)/CC) 3 17007/CC L1 1038 HYPOGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17006/CC OR ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC ACTIVITY/CC OR 17007/CC 2 This search retrieves records with the searched classification codes such as the ones shown here.