The Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Modern Art Painting Sculpture Architecture Photography

HISTORY OF MODERN ART PAINTING SCULPTURE ARCHITECTURE PHOTOGRAPHY SEVENTH EDITION LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd i 14/09/2012 15:49 LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd ii 14/09/2012 15:49 HISTORY OF MODERN ART PAINTING SCULPTURE ARCHITECTURE PHOTOGRAPHY SEVENTH EDITION H.H. ARNASON ELIZABETH C. MANSFIELD National Humanities Center Boston Columbus Indianapolis New York San Francisco Upper Saddle River Amsterdam Cape Town Dubai London Madrid Milan Munich Paris Montréal Toronto Delhi Mexico City São Paulo Sydney Hong Kong Seoul Singapore Taipei Tokyo LK024_P0001EDarmason_HoMA_FM_Combined.indd iii 14/09/2012 15:49 Editorial Director: Craig Campanella This book was designed and produced by Editor-in-Chief: Sarah Touborg Laurence King Publishing Ltd, London Senior Sponsoring Editor: Helen Ronan www.laurenceking.com Editorial Assistant: Victoria Engros Production Manager: Simon Walsh Vice President, Director of Marketing: Brandy Dawson Page Design: Robin Farrow Executive Marketing Manager: Kate Mitchell Photo Researcher: Emma Brown Editorial Project Manager: David Nitti Copy Editor: Lis Ingles Production Liaison: Barbara Cappuccio Managing Editor: Melissa Feimer Senior Operations Supervisor: Mary Fischer Operations Specialist: Diane Peirano Senior Digital Media Editor: David Alick Media Project Manager: Rich Barnes Cover photo: Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, 1912 (detail). Oil on canvas, 58 ϫ 35” (147.3 ϫ 88.9 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art. page 2: Georges Seurat, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884–86 (detail). 1 1 Oil on canvas, 6’ 9 ∕2” ϫ 10’ 1 ∕4” (2.1 ϫ 3.1 m). The Art Institute of Chicago. Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on the appropriate page within text or in the picture credits on pages 809–16. -

Pablo Picasso, One of the Most He Was Gradually Assimilated Into Their Dynamic and Influential Artists of Our Stimulating Intellectual Community

A Guide for Teachers National Gallery of Art,Washington PICASSO The Early Ye a r s 1892–1906 Teachers’ Guide This teachers’ guide investigates three National G a l l e ry of A rt paintings included in the exhibition P i c a s s o :The Early Ye a rs, 1 8 9 2 – 1 9 0 6.This guide is written for teachers of middle and high school stu- d e n t s . It includes background info r m a t i o n , d i s c u s s i o n questions and suggested activities.A dditional info r m a- tion is available on the National Gallery ’s web site at h t t p : / / w w w. n g a . gov. Prepared by the Department of Teacher & School Programs and produced by the D e p a rtment of Education Publ i c a t i o n s , Education Division, National Gallery of A rt . ©1997 Board of Tru s t e e s , National Gallery of A rt ,Wa s h i n g t o n . Images in this guide are ©1997 Estate of Pa blo Picasso / A rtists Rights Society (ARS), New Yo rk PICASSO:The EarlyYears, 1892–1906 Pablo Picasso, one of the most he was gradually assimilated into their dynamic and influential artists of our stimulating intellectual community. century, achieved success in drawing, Although Picasso benefited greatly printmaking, sculpture, and ceramics from the artistic atmosphere in Paris as well as in painting. He experiment- and his circle of friends, he was often ed with a number of different artistic lonely, unhappy, and terribly poor. -

The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5786 Chapter 3: The Most Important Works of Art of the Twentieth Century Introduction Quality in art is not just a matter of private experience. There is a consensus of taste. Clement Greenberg1 Important works of art embody important innovations. The most important works of art are those that announce very important innovations. There is considerable interest in identifying the most important artists, and their most important works, not only among those who study art professionally, but also among a wider public. The distinguished art historian Meyer Schapiro recognized that this is due in large part to the market value of works of art: “The great interest in painting and sculpture (versus poetry) arises precisely from its unique character as art that produces expensive, rare, and speculative commodities.”2 Schapiro’s insight suggests one means of identifying the most important artists, through analysis of prices at public sales.3 This strategy is less useful in identifying the most important individual works of art, however, for these rarely, if ever, come to market. An alternative is to survey the judgments of art experts. One way to do this is by analyzing textbooks. -

Recycled Cubist Sculpture

Recycled Cubist Sculpture Grade: 5th Medium: Cardboard, paint, mixed media Learning Objective: Students will: • Become familiar with art vocabulary • Observe Cubist art • Build a sturdy sculpture • Use detail to create interest • Use good craftsmanship Author: Cynthia Moring Elements of Art Form: a 3-dimensional figure that exists in space instead of flat on paper. This lesson uses geometric forms, instead of natural or organic. Shape: is two-dimensional (flat), limited to height and width. A two-dimensional (flat) area enclosed by a line. This lesson uses geometric shapes: symmetrical, straight edged. Texture: actual texture is how something feels when touched; visual texture (also called simulated texture) is how something appears to feel. Principles of Design Asymmetrical balance: a form or shape in which neither side is the same as the other but they still make a whole, with equally important sides. Contrast: A technique that shows differences in the elements of visual arts in an artwork. In this lesson it is heart against the complimentary-colored background. Focal Point: the part of an artwork that is emphasized in some way and attracts the eye and attention of the viewer; also called the center of interest. Movement: How the artist makes the viewer’s eye move around the composition. Unity: the connecting of parts of a work of art, creating a feeling of peace and a sense of completeness. All parts should work together. Not enough unity is chaotic to the viewer, while too much unity is boring. Additional Vocabulary Abstract: an artwork that uses color, line, shape or form to create a composition which may or may not have any visual reference to the world. -

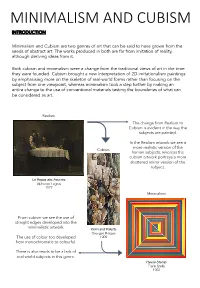

Minimalism and Cubism Introduction

MINIMALISM AND CUBISM INTRODUCTION Minimalism and Cubism are two genres of art that can be said to have grown from the seeds of abstract art. The works produced in both are far from imitation of reality, although deriving ideas from it. Both cubism and minimalism were a change from the traditional views of art in the time they were founded. Cubism brought a new interpretation of 2D imitationalism paintings by emphasising more on the skeleton of real-world forms rather than focusing on the subject from one viewpoint, whereas minimalism took a step further by making an entire change to the use of conventional materials testing the boundaries of what can be considered as art. Realism The change from Realism to Cubism is evident in the way the subjects are painted. In the Realism artwork we see a more realistic version of the Cubism human subjects, whereas the cubism artwork portrays a more shattered mirror version of the subject. Le Repas des Pauvres Alphonse Legros 1877 Minimalism From cubism we see the use of straight edges developed into the minimalistic artwork. Violin and Palette Georges Braque The use of colour too developed 1909 from monochromatic to colourful. There is also tends to be a lack of real world subjects in this genre. Hyena Stomp Frank Stella 1962 CUBISM It began in the early 1900s after Picasso’s creation of “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” in 1907. The genre mainly consisted of paintings that followed a monochromatic palette to keep the viewer’s focus on the structure of the subject in the work In contrast to the growing movements at the time such as fauvism, expressionism, etc. -

Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1968 Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914 Carl W. Brodin Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons Recommended Citation Brodin, Carl W., "Effects of Cubism on American Painting Since 1914" (1968). All Master's Theses. 811. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/811 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECTS OF CUBISM ON AMERICAN PAINTING SINCE 1914 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington State College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Carl W. Brodin August, 1968 . ,0.1 -y;J \':fjcl'i> APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY ________________________________ Edward C. Haines, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN _________________________________ Louis A. Kollmeyer _________________________________ Alexander H. Howard, Jr. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION OF TERMS USED 1 The Problem 1 Scope of the problem 1 Limitations of the study . 2 Importance of the study 2 Definition of Terms . 3 Analysis, analytical 3 Sensational . 3 Synthetic, synthesis 3 II. SEARCH OF THE LITERATURE 4 III. PROCEDURE OF THE STUDY 6 IV. TREATMENT OF SELECTED WRITINGS AND ILLUSTRATIONS • 7 V. ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS OF THE STUDY 37 VI. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER STUDY 43 BIBLIOGRAPHY • 44 APPENDIX 46 CHAPTER I THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION OF TERMS USED The writer assumes that Cubism has had a significant effect on American Art. -

Cubism Was One of the First Truly Modern Movements to Emerge in Art

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Cubism was one of the first truly modern movements to emerge in art. It evolved during a period of heroic and rapid innovation between Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. The movement has been described as having two stages: 'Analytic' Cubism, in which forms seem to be 'analyzed' and fragmented; and 'Synthetic' Cubism, in which newspaper and other foreign materials such as chair caning and wood veneer, are collaged to the surface of the canvas as 'synthetic' signs for depicted objects. The style was significantly developed by Fernand Léger and Juan Gris, but it attracted a host of adherents, both in Paris and abroad, and it would go on to influence the Abstract Expressionists, particularly Willem de Kooning. Key Points • Analytic Cubism staged modern art's most radical break with traditional models of representation. It abandoned perspective, which artists had used to order space since the Renaissance. And it turned away from the realistic modeling of figures and towards a system of representing bodies in space that employed small, tilted planes, set in a shallow space. Over time, Picasso and Braque also moved towards open form - they pierced the bodies of their figures, let the space flow through them, and blended background into foreground. Some historians have argued that its innovations represent a response to the changing experience of space, movement, and time in the modern world. • Synthetic Cubism proved equally important and influential for later artists. Instead of relying on depicted shapes and forms to represent objects, Picasso and Braque began to explore the use of foreign objects as abstract signs. -

Cubism and Australian Art and Its Accompanying Book of the Same Title Explore the Impact of Cubism on Australian Artists from the 1920S to the Present Day

HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Melinda Harper Untitled 2000 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased through the National Gallery of Victoria Foundation by Robert Gould, Benefactor, 2004 This Education Resource has been produced by Heide Museum of Modern Art to provide information to support education institution visits to the exhibition Cubism & Australian Art and as such is intended for their use only. Reproduction and communication is permitted for educational purposes only. No part of this education resource may be stored in a retrieval system, communicated or transmitted in any form or by any means. HEIDE EDUCATION RESOURCE Heide Education is committed to providing a stimulating and dynamic range of quality programs for learners and educators at all levels to complement that changing exhibition schedule. Programs range from introductory tours to intensive forums with artists and other arts professionals. Designed to broaden and enrich curriculum requirements, programs include immersive experiences and interactions with art in addition to hands-on creative artmaking workshops which respond to the local environs. Through inspiring programs and downloadable support resources our aim is to foster deeper appreciation, stimulate curiosity and provoke creative thinking. Heide offers intensive and inspiring professional development opportunities for educators, trainee teachers and senior students. Relevant links to VELS and the VCE are incorporated into each program with lectures, floor talks and workshops by educators, historians and critics. Exclusive professional development sessions to build the capacity and capability of your team can be planned for your staff and potentially include exhibition viewings, guest speakers, catering, and use of the Sidney Myer Education Centre. If you would like us to arrange a PD just for your group please contact the Education Coordinator to discuss your individual requirements. -

Pablo Picasso

PABLO PICASSO The Father of Cubism OBJECTIVES ➢ identify facial proportions of both a frontal and a profile view. ➢ learn to create a portrait by both observing and measuring. ➢ investigate facial proportions and contour line drawing. ➢ Cubism will be introduced and the role of Picasso in its development. ➢ understand the expression involved in Cubism and the creative procedures involved in creating a piece of Cubist art. ➢ create a multi-media portrait using their newfound knowledge of Picasso. VOCABULARY Proportion Portrait Observation Frontal Profile Feature Symmetry Measurement Picasso Cubism Arrangement Negative Space Expression Abstract MATERIALS 18 x 24" white paper Mirror Portfolio cover Erasers Crayons Masking Tape Pencils Colored Pencils Watercolor Paints Sharpie Markers Tempera Paint Markers Rulers Introduction Born in Malaga, Spain on October 25, 1881, Pablo Picasso is considered by many art historians to be the greatest artist of the 20th century. He invented forms of graphic and sculptural expression that gave new definition to the modern art movement. Picasso in his studio Early Years At around the age of 10 he made his first paintings, and his natural genius became evident immediately. When he was 15 he took the entrance examinations at Barcelona's School of Fine Arts. These exams usually lasted for an entire month. Young Pablo completed them in a single day. Autoportrait (1899-1900), Charcoal on paper, Museum Picasso Blue Period At around 1901, Picasso entered what is known as his "blue period". His blue period lasted until 1904. These works are powerful expressions of human misery, featuring blind figures, beggars, and alcoholics. 1999 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Bridgeman Art Library, London/New York Rose Period 1905 and 1906 is known as Picasso's "Rose Period". -

The Sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz

The sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz Author Hope, Henry R. (Henry Radford), 1905- 1989 Date 1954 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by Simon & Schuster Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2913 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art The Sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz 96 pages; 100 plates $3.00 The Sculpture of Jacques Lipchitz BY HENRY R. HOPE No other sculptor of Lipchitz' generation can show such multifarious variety of style or so great a range of feeling. His art matured under the stimulus, and within the discipline, of cubism whose sculptural potentialities he brilliantly ex plored for over ten years. Since the thirties, his work has shown a vigor and eloquence which allies him with the tradition of Bernini and Rodin. Central to Lipchitz' evolution as an artist is the transition from the impersonal collective style of cubism to an art more personal in accent and theme. This transition is studied in detail by Mr. Hope, who gives special attention to his transparents, the revolutionary, small, open- form bronzes, cast in the difficult "lost wax" technique which marked the turning point in his own art and were to have widespread influence. In this first monograph on the artist in English, one hundred plates illustrate all periods of his career, including each of his major large-scale sculptures. Related drawings supplement the sculpture, and many small terracotta sketches document the original inspiration for several master works. -

Imogen Racz Volume 1

HENRI LAURENS AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE IMOGEN RACZ NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 099 19778 0 -' ,Nesis L6 VOLUME 1 Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD. The University of Newcastle. 2000. Abstract This dissertation examines the development of Henri Laurens' artistic work from 1915 to his death in 1954. It is divided into four sections: from 1915 to 1922, 1924 to 1929, 1930 to 1939 and 1939 to 1954. There are several threads that run through the dissertation. Where relevant, the influence of poetry on his work is discussed. His work is also analyzed in relation to that of the Parisian avant-garde. The first section discusses his early Cubist work. Initially it reflected the cosmopolitan influences in Paris. With the continuation of the war, his work showed the influence both of Leonce Rosenberg's 'school' of Cubism and the literary subject of contemporary Paris. The second section considers Laurens' work in relation to the expanding art market. Laurens gained a number of public commissions as well as many ones for private clients. Being site specific, all the works were different. The different needs of architectural sculpture as opposed to studio sculpture are discussed, as is his use of materials. Although the situation was not easy for avant-garde sculptors, Laurens became well respected through exposure in magazines and exhibitions. The third section considers Laurens in relation to the depression and the changing political scene. Like many of the avant-garde, he had left wing tendencies, which found form in various projects, including producing a sculpture for the Ecole Karl Marx at Villejuif. -

• Continually Reinvented His Art & Changed the Art World Forever He

As we said last week, along with Matisse one of most important innovators of 20th century art, but many would argue that Picasso was the most important artist of the 20th century. He was a painter first, put also created sculpture, ceramics, drawing, prints He said, "Paintings... tiles... sculptures... back to painting. The combination is good ‐ like salad.“ Kept a visual diary Continually reinvented his art & changed the art world forever He was strong-willed, independent, egotistical, high energy – the original bad boy! And no biography of Picasso would be complete without talking his passion for women and his relationships – a true macho man We’ll start with a brief bio video 1 http://www.biography.com/people/pablo‐picasso‐9440021/videos/pablo‐picasso‐mini‐ biography‐2189594028 2 The Picador, 1890 Painted when he was just 9 Hinted at artistic genius Pablo Ruiz Picasso was born in 1881 in Málaga, Spain to José Ruiz Blasco and María Picasso López His baptized name was Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Martyr Patricio Clito Ruíz y Picasso He took his mother’s maiden name of Picasso His father was an artist, a drawing teacher, and curator of an art museum By age of 4, Picasso could draw very well and was showing signs of early artistic genius This was a painting he did when he was just 9 years old 3 First Communion, 1896, oil on canvas, Museo Picasso, Barcelona 1895 the family moved to Barcelona. His father was teaching in Barcelona at Fine Arts Academy.