Qiaowu and the Overseas Chinese

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTH KOREA BETWEEN EAGLE and DRAGON Perceptual Ambivalence and Strategic Dilemma

SOUTH KOREA BETWEEN EAGLE AND DRAGON Perceptual Ambivalence and Strategic Dilemma Jae Ho Chung The decade of the 1990s began with the demise of the Soviet empire and the subsequent retreat of Russia from the center stage of Northeast Asia, leaving the United States in a search to adjust its policies in the region. The “rise of China,” escalating cross-strait tension since 1995, North Korea’s nuclear brinkmanship and missile challenges, latent irreden- tism, and the pivotal economic importance of Northeast Asia have all led the United States to re-emphasize its role and involvement in the region.1 This redefinition of the American mission has in turn led to the consolidation of the U.S.-Japan alliance, exemplified by the 1997 Defense Guideline revision, as well as to the establishment of trilateral consultative organizations such as the Trilateral Coordination and Oversight Group (TCOG) among the U.S., Japan, and South Korea. The increasingly proactive posture by the U.S. has, however, generated grave strategic concerns on the part of China and Russia, which have sought to circumscribe America’s hegemonic parameters in Asia both bilaterally and multilaterally (i.e., the formation of the “Shanghai Six” and the Boao Asia Forum, as well as China’s call for an Association of Southeast Asian Nations Jae Ho Chung is Associate Professor of International Relations, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea. The author wishes to thank Bruce J. Dickson and Wu Xinbo for their helpful comments on an earlier version. Asian Survey, 41:5, pp. 777–796. ISSN: 0004–4687 Ó 2001 by The Regents of the University of California. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

1 May 2016 U.S.-Japan-China Trilateral Report by Sheila Smith

May 2016 U.S.-Japan-China Trilateral Report By Sheila Smith June 2016 Introduction The Forum on Asia-Pacific Security (FAPS) of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy (NCAFP) hosted a one-and-a-half day Track 1.5 meeting in New York City on May 24-25, 2016, with participants from the United States, Japan and China. The participant list for the trilateral meeting appears in the appendix. This report is not so much an effort to summarize the rich discussion at the trilateral meetings, as it is an effort to analyze the complex and fragile nature of trilateral relations today and to offer suggestions to all three sides for improvement in their ties with each other. In contrast to our November 2015 report, which focused on the interactions between and among the bilateral relationships that comprise this trilateral, this meeting focused on the changing regional security balance and the tension between national strategies and regional institutions which might impede cooperation in resolving the growing tensions in the Asia-Pacific. I. Context Japan, China, and the United States once again found common purpose in the wake of North Korean nuclear and missile tests in early 2016. Pyongyang’s continued insistence on developing a nuclear arsenal resulted in a new United Nations Security Council resolution and stronger sanctions on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). China took some time to agree, prompting concerns yet again in Tokyo and Washington that Beijing was reluctant to punish Kim Jong Un for his belligerence. After Special Representative for Korean Peninsula Affairs Wu Dawei visited Pyongyang in early February,1 Beijing’s position solidified, however, and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Washington, DC three weeks later to meet U.S. -

Woman Warns Others After House Burgled

SOUTH ISLAND EDITION press.co.nz MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 2010 Retail $1.40 MPs want Break-in drives family from home travel perk scrapped Andrea Vance WHAT THEY GET MPs across the political Backbench MPs are paid $131,000 a year before allowances. spectrum are calling for their The Remuneration Authority sets the base rate of their wage private travel perks to be and the Speaker decides on other entitlements such as scrapped after the resignation travel and office expenses. They are entitled to: of cabinet minister Pansy ■ Domestic travel, but this is not restricted to work-related Wong. trips. The Remuneration Authority considers 5 per cent of this Prime Minister John Key as a benefit and so deducts $1500 from each MP’s salary. said yesterday there was ‘‘a ■ Domestic travel for spouses/partners – as long as they are time and a place’’ for looking not conducting business. As this is also a benefit, a further at the travel perks. $3400 comes out of each MP’s salary. Speaking from Japan ■ Four free flights a year between Wellington and their home where he is attending the base for children of MPs. It is unlimited for under fives. Apec summit he said: ‘‘It’s ■ Discounted international travel for MPs, as long as they are possible there may need to be not conducting private business. some change but today’s not ■ Discounted international travel for their spouses, who must the day to make those not be travelling on business. comments. ‘‘It’s tripped up a number of MPs and that’s very unfor- ing a free travel privilege as a not sure that will ever mollify tunate. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

Comparative Connections a Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations China-Korea Relations: Year of China-DPRK Friendship; North’s Rocket Fizzles Scott Snyder Asia Foundation/Pacific Forum CSIS See-won Byun, Asia Foundation Top-level diplomacy between Beijing and Pyongyang intensified this quarter in honor of China- DPRK Friendship Year and the 60th anniversary of diplomatic relations. Prior to the Lunar New Year holiday in mid-January, Kim Jong-il held his first public meeting since his reported illness with Chinese Communist Party International Liaison Department Head Wang Jiarui. In March, DPRK Prime Minister Kim Yong-il paid a return visit to Beijing. The Chinese have accompanied these commemorative meetings with active diplomatic interaction with the U.S., South Korea, and Japan focused on how to respond to North Korea’s launch of a multi-stage rocket. Thus, China finds itself under pressure to dissuade Pyongyang from destabilizing activity and ease regional tensions while retaining its 60-year friendship with the North. Meanwhile, South Korean concerns about China’s rise are no longer confined to issues of economic competitiveness; the Korea Institute for Defense Analysis has produced its first public assessment of the implications of China’s rising economic capabilities for South Korea’s long- term security policies. The response to North Korea’s rocket launch also highlights differences in the respective near-term positions of Seoul and Beijing. Following years of expanding bilateral trade and investment ties, the global financial crisis provides new challenges for Sino- ROK economic relations: how to manage the fallout from a potential decline in bilateral trade and the possibility that domestic burdens will spill over and create new strains in the relationship. -

China's Political Influence Activities Under Xi Jinping Professor

Magic Weapons: China's political influence activities under Xi Jinping Professor Anne-Marie Brady Global Fellow, Wilson Center, Washington, DC; Department of Political Science and International Relations University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand In September 2014 Xi Jinping gave a speech on the importance of united front work— political influence activities—calling it one of the CCP’s “magic weapons”. The Chinese government’s foreign influence activities have accelerated under Xi. China’s foreign influence activities have the potential to undermine the sovereignty and integrity of the political system of targeted states. Conference paper presented at the conference on “The corrosion of democracy under China’s global influence,” supported by the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, and hosted in Arlington, Virginia, USA, September 16-17, 2017. Key points: • CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping is leading an accelerated expansion of political influence activities worldwide. • The expansion of these activities is connected to both the CCP government’s domestic pressures and foreign agenda. • The paper creates a template of the policies and modes of China’s expanded foreign influence activities in the Xi era. • The paper uses this template to examine the extent to which one representative small state, New Zealand, is being targeted by China’s new influence agenda. Executive Summary In June 2017 the New York Times and The Economist featured stories on China's political influence in Australia. The New York Times headline asked "Are Australia's Politics too Easy to Corrupt?,"1 while The Economist sarcastically referred to China as the "Meddle Country."2 The two articles were reacting to an investigation by Fairfax Media and ABC into the extent of China's political interference in Australia,3 that built on internal enquiries into the same issue by ASIO and Australia's Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet in 2015 and 2016. -

Zhou Fengsuo Looks Back at Humanitarian China's Journey in 2019 in an Interview (Full Transcript)

Video link: https://youtu.be/tmaJzU0Fyxw Zhou Fengsuo looks back at Humanitarian China's journey in 2019 in an interview (full transcript) Host: This is the Chen Pokong Fengyun Show and I am special correspondent Wu Yun. Today, we’ve invited Mr Zhou Fengsuo, former student leader during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 and president of Humanitarian China. Welcome, Mr Zhou. We would like you to tell us about Humanitarian China’s work during 2019 and its future plans . Zhou Fengsuo: Thank you. It’s a privilege for me to have the opportunity to talk about our work during the past year and our future plans. During the past year, human rights in China continued to deteriorate, which brought us huge challenges. The need is great. The most important work Humanitarian China does is to assist prisoners of conscience in China; we provide humanitarian relief to over 100 people annually. This group now consists of a wide range of people, including groups we have been supporting such as human rights lawyers, former Democracy Party members and Tiananmen Square Massacre victims, and some new groups that have emerged this year, for instance, the Hong Kong protesters and those arrested over rights issues that had previously been regarded as relatively minor in China, for instance, labor rights, woman rights and equality. The CCP is becoming increasingly paranoid and treating everyone as an enemy, which results in many different groups being targeted. We do our best to provide humanitarian relief. Our most crucial task is to understand their situation and needs, and to promote international awareness of human rights violations. -

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared

Recent Articles from the China Journal of System Engineering Prepared by the University of Washington Quantum System Engineering (QSE) Group.1 Bibliography [1] Mu A-Hua, Zhou Shao-Lei, and Yu Xiao-Li. Research on fast self-adaptive genetic algorithm and its simulation. Journal of System Simulation, 16(1):122 – 5, 2004. [2] Guan Ai-Jie, Yu Da-Tai, Wang Yun-Ji, An Yue-Sheng, and Lan Rong-Qin. Simulation of recon-sat reconing process and evaluation of reconing effect. Journal of System Simulation, 16(10):2261 – 3, 2004. [3] Hao Ai-Min, Pang Guo-Feng, and Ji Yu-Chun. Study and implementation for fidelity of air roaming system above the virtual mount qomolangma. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):356 – 9, 2000. [4] Sui Ai-Na, Wu Wei, and Zhao Qin-Ping. The analysis of the theory and technology on virtual assembly and virtual prototype. Journal of System Simulation, 12(4):386 – 8, 2000. [5] Xu An, Fan Xiu-Min, Hong Xin, Cheng Jian, and Huang Wei-Dong. Research and development on interactive simulation system for astronauts walking in the outer space. Journal of System Simulation, 16(9):1953 – 6, Sept. 2004. [6] Zhang An and Zhang Yao-Zhong. Study on effectiveness top analysis of group air-to-ground aviation weapon system. Journal of System Simulation, 14(9):1225 – 8, Sept. 2002. [7] Zhang An, He Sheng-Qiang, and Lv Ming-Qiang. Modeling simulation of group air-to-ground attack-defense confrontation system. Journal of System Simulation, 16(6):1245 – 8, 2004. [8] Wu An-Bo, Wang Jian-Hua, Geng Ying-San, and Wang Xiao-Feng. -

The Politics of Presence: Political Representation and New Zealand’S Asian Members of Parliament

THE POLITICS OF PRESENCE: POLITICAL REPRESENTATION AND NEW ZEALAND’S ASIAN MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT By Seonah Choi A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science at Victoria University of Wellington 2014 2 Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................... 4 List of Tables ......................................................................................................................... 5 Definitions ............................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter I: Introduction .......................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II: Literature Review .............................................................................................. 11 2.1 Representative Democracy ........................................................................................ 11 2.2 Theories of Political Representation .......................................................................... 12 2.3 Theories of Minority Representation ......................................................................... 27 2.4 Formulating a Framework ........................................................................................ -

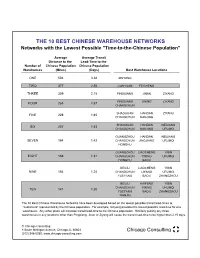

10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-To-The-Chinese Population"

THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Average Average Transit Distance to the Lead-Time to the Number of Chinese Population Chinese Population Warehouses (Miles) (Days) Best Warehouse Locations ONE 504 3.38 XINYANG TWO 377 2.55 LIANYUAN FEICHENG THREE 309 2.15 PINGXIANG JINAN ZIYANG PINGXIANG JINING ZIYANG FOUR 265 1.87 CHANGCHUN SHAOGUAN HANDAN ZIYANG FIVE 228 1.65 CHANGCHUN NANJING SHAOGUAN HANDAN NEIJIANG SIX 207 1.53 CHANGCHUN NANJING URUMQI GUANGZHOU HANDAN NEIJIANG SEVEN 184 1.42 CHANGCHUN JINGJIANG URUMQI HONGHU GUANGZHOU LIAOCHENG YIBIN EIGHT 168 1.31 CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI HONGHU BAOJI BEILIU LIAOCHENG YIBIN NINE 154 1.24 CHANGCHUN LIYANG URUMQI YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU BEILIU KAIFENG YIBIN CHANGCHUN YIXING URUMQI TEN 141 1.20 YUEYANG BAOJI ZHANGZHOU TIANJIN The 10 Best Chinese Warehouse Networks have been developed based on the lowest possible transit lead-times to "customers" represented by the Chinese population. For example, Xinyang provides the lowest possible lead-time for one warehouse. Any other place will increase transit lead-time to the Chinese population. Similarly putting any three warehouses in any locations other than Pingxiang, Jinan or Ziyang will cause the transit lead-time to be higher than 2.15 days. © Chicago Consulting 8 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, IL 60603 Chicago Consulting (312) 346-5080, www.chicago-consulting.com THE 10 BEST CHINESE WAREHOUSE NETWORKS Networks with the Lowest Possible "Time-to-the-Chinese Population" Best One City