Online Islamophobia After the Brussels Attacks on March 22Nd 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activity Report 2016

ACTIVITY REPORT 2016 ACTIVITY REPORT 2016 Review Investigations, Control of Special Intelligence Methods and Recommendations Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee Cambridge – Antwerp – Portland Th e Dutch and French language versions of this report are the offi cial versions. In case of confl ict between the Dutch and French language versions and the English language version, the meaning of the fi rst ones shall prevail. Activity Report 2016. Review Investigations, Control of Special Intelligence Methods and Recommendations Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee Belgian Standing Intelligence Agencies Review Committee Rue de Louvain 48, 1000 Brussels – Belgium + 32 (0)2 286 29 11 [email protected] www.comiteri.be © 2018 Intersentia Cambridge – Antwerp – Portland www.intersentia.com ISBN 978-1-78068-642-4 D/2018/7849/27 NUR 823 All rights reserved. Nothing from this report may be reproduced, stored in an automated database or made public in any way whatsoever without the express prior consent of the publishers, except as expressly required by law. CONTENTS List of abbreviations . vii Introduction . xi ACTIVITY REPORT 2016 Table of contents of the complete Activity Report . 3 Preface . 9 Review investigations . 11 Control of special intelligence methods . 85 Recommendations . 113 APPENDICES Extract of the Act of 18 July 1991 governing Review of the Police and Intelligence Services and the Coordination Unit for Th reat Assessment . 125 Extract of the Act of 30 November 1998 governing the Intelligence and Security Services . 143 v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BCC Belgian Criminal Code BCCP Belgian Code of Civil Procedure BICS Belgacom International Carrier Services BOJ Belgian Offi cial Journal CCB Centre for Cybersecurity Belgium (Centrum voor Cybersecurity België – Centre pour la cybersécurité Belgique) CCIRM Collection coordination and intelligence requirements management CHOD Chief of Defence C.O.C. -

Group Support and Cognitive Dissonance 1 I'ma

Group support and cognitive dissonance 1 I‘m a Hypocrite, but so is Everyone Else: Group Support and the Reduction of Cognitive Dissonance Blake M. McKimmie, Deborah J. Terry, Michael A. Hogg School of Psychology, University of Queensland Antony S.R. Manstead, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam Running head: Group support and cognitive dissonance. Key words: cognitive dissonance, social identity, social support Contact: Blake McKimmie School of Psychology The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Phone: +61 7 3365-6406 Fax: +61 7 3365-4466 Group support and cognitive dissonance 2 [email protected] Abstract The impact of social support on dissonance arousal was investigated to determine whether subsequent attitude change is motivated by dissonance reduction needs. In addition, a social identity view of dissonance theory is proposed, augmenting current conceptualizations of dissonance theory by predicting when normative information will impact on dissonance arousal, and by indicating the availability of identity-related strategies of dissonance reduction. An experiment was conducted to induce feelings of hypocrisy under conditions of behavioral support or nonsupport. Group salience was either high or low, or individual identity was emphasized. As predicted, participants with no support from the salient ingroup exhibited the greatest need to reduce dissonance through attitude change and reduced levels of group identification. Results were interpreted in terms of self -

Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq

Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq An Analysis of open-source intelligence and statistical data Linus Gustafsson Magnus Ranstorp Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq An analysis of open-source intelligence and statistical data Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq An analysis of open-source intelligence and statistical data Authors: Linus Gustafsson Magnus Ranstorp Swedish Defence University 2017 Swedish Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq: An analysis of open-source intelligence and statistical data Linus Gustafsson & Magnus Ranstorp © Swedish Defence University, Linus Gustafsson & Magnus Ranstorp 2017 No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. Swedish material law is applied to this book. The contents of the book has been reviewed and authorized by the Department of Security, Strategy and Leadership. Printed by: Arkitektkopia AB, Bromma 2017 ISBN 978-91-86137-64-9 For information regarding publications published by the Swedish Defence University, call +46 8 553 42 500, or visit our home page www.fhs.se/en/research/internet-bookstore/. Summary Summary The conflict in Syria and Iraq has resulted in an increase in the number of violent Islamist extremists in Sweden, and a significant increase of people from Sweden travelling to join terrorist groups abroad. Since 2012 it is estimated that about 300 people from Sweden have travelled to Syria and Iraq to join terrorist groups such as the Islamic State (IS) and, to a lesser extent, al-Qaeda affiliated groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra. Even though the foreign fighter issue has been on the political agenda for several years and received considerable media attention, very little is known about the Swedish contingent. -

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated With

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated with the Bounded Confidence XY Model, Parameterized by Twitter Data Maksym Romenskyy Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK and Department of Mathematics, Uppsala University, Box 480, Uppsala 75106, Sweden Viktoria Spaiser School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Thomas Ihle Institute of Physics, University of Greifswald, Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 6, Greifswald 17489, Germany Vladimir Lobaskin School of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (Dated: July 26, 2018) Multiple countries have recently experienced extreme political polarization, which in some cases led to escalation of hate crime, violence and political instability. Beside the much discussed presi- dential elections in the United States and France, Britain’s Brexit vote and Turkish constitutional referendum, showed signs of extreme polarization. Among the countries affected, Ukraine faced some of the gravest consequences. In an attempt to understand the mechanisms of these phe- nomena, we here combine social media analysis with agent-based modeling of opinion dynamics, targeting Ukraine’s crisis of 2014. We use Twitter data to quantify changes in the opinion divide and parameterize an extended Bounded-Confidence XY Model, which provides a spatiotemporal description of the polarization dynamics. We demonstrate that the level of emotional intensity is a major driving force for polarization that can lead to a spontaneous onset of collective behavior at a certain degree of homophily and conformity. We find that the critical level of emotional intensity corresponds to a polarization transition, marked by a sudden increase in the degree of involvement and in the opinion bimodality. -

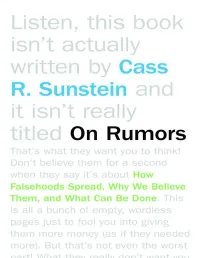

On Rumors Also by Cass R

On Rumors Also by Cass R. Sunstein Simpler: The Future of Government Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard Thaler) Worst-Case Scenarios Republic.com 2.0 Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge The Second Bill of Rights: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle Why Societies Need Dissent Risk and Reason: Safety, Law, and the Environment One Case at a Time Free Markets and Social Justice Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict Democracy and the Problem of Free Speech The Partial Constitution After the Rights Revolution On Rumors How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done Cass R. Sunstein With a new afterword by the author Princeton University Press • Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2014 by Cass R. Sunstein Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Originally published in North America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2009 First Princeton Edition 2014 ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-16250-8 LCCN 2013950544 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper. -

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration Marina Lindell (Åbo Akademi University), André Bächtiger (University of Stuttgart), Kimmo Grönlund (Åbo Akademi University), Kaisa Herne (University of Tampere), Maija Setälä (University of Turku) Abstract In the study of deliberation, a largely underexplored area is why some participants become more extreme, whereas some become more moderate. Opinion polarization is usually considered a suspicious outcome of deliberation, while moderation is seen as a desirable one. This article takes issue with this view. Results from a deliberative experiment on immigration show that polarizers and moderators were not different in their socio-economic, cognitive, or affective profiles. Moreover, both polarization and moderation can entail deliberatively desired pathways: in the experiment, both polarizers and moderators learned during deliberation, levels of empathy were fairly high on both sides, and group pressures barely mattered. Finally, the absence of a participant with an immigrant background in a group was associated with polarization in anti-immigrant direction, bolstering longstanding claims regarding the importance of presence in interaction (Philips 1995). Paper presented at the “13ème Congrès National Association Française de Science Politique (AFSP), Aix-en-Provence, June 22–24, 2015 1 Introduction Empirical studies of citizen deliberation suggest that participants often change opinions (and also quite radically; see, e.g., Fishkin, 2009). Luskin et al. (2002) claim that knowledge gain is an important mechanism of opinion change, whereas Sanders (2012) was unable to identify any robust predictor of opinion change in a recent study based on a pan-European deliberative poll (Europolis). A largely understudied area in this regard is why some participants polarize their opinions due to deliberation, and why others moderate them. -

APR 2016 Part C.Pdf

Page | 1 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – April 2016 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Page | 2 CBRNE-TERRORISM NEWSLETTER – April 2016 After Brussels, Europe's intelligence woes revealed Source:http://www.cnbc.com/2016/03/22/brussels-attack-why-europe-must-increase-terror- intelligence.html Mar 23 – Europe must improve the regional Rudd's comments are at the crux of a hot- sharing of intelligence to successfully button discourse about the encroachment on combat the rise of homegrown militants, civil liberties should governments ramp up policy experts told CNBC a day after deadly surveillance and detainment tactics in the explosions hit Brussels. global war on terror. Global terrorist organization ISIS claimed Rudd believes it's a necessary cost to bear. responsibility for Tuesday's attacks that killed "This is not a normal set of circumstances, at least 31 people, the latest episode in the we've got to give our men and women in group's campaign of large-scale violence on uniform and in the intelligence services the the international stage. powers necessary to deal with this. This is no Recent offensives in Paris and Jakarta indicate criticism of the Belgian government but a wake- ISIS is increasingly relying on local up call to all of us who wrestle with this fundamentalists, typically trained in ISIS debate." strongholds within the Middle East, to execute Others agree that European officials must suicide bombings and shootings in busy direct more investment to counter-terrorism, metropolitan areas. despite strained finances for most countries in "The key question here is closing the the region. intelligence gap," said Kevin Rudd, former The fact that the perpetrator of December's Prime Minister of Australia and president of the Paris attacks was caught in Belgium four Asia Society Policy Institute. -

In Der Berichterstattung Über Die Anschläge

EINE KONTRASTIVE BEGRIFFSANALYSE DES SPRACHGEBRAUCHS (DEUTSCH UND NIEDERLÄNDISCH) IN DER BERICHTERSTATTUNG ÜBER DIE ANSCHLÄGE VON BRÜSSEL MIXED METHODS STUDIE AUF BASIS EINES SELBST ERSTELLTEN KORPUS VON DEUTSCHEN UND FLÄMISCHEN ZEITUNGS- UND ZEITSCHRIFTARTIKELN Aantal woorden: 16.706 Lisa De Brabant Studentennummer: 01306076 Promotor: Prof. dr. Carola Strobl Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in het Vertalen Academiejaar: 2017 – 2018 Verklaring i.v.m. auteursrecht De auteur en de promotor(en) geven de toelating deze studie als geheel voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting de bron uitdrukkelijk te vermelden bij het aanhalen van gegevens uit deze studie. Het auteursrecht betreffende de gegevens vermeld in deze studie berust bij de promotor(en). Het auteursrecht beperkt zich tot de wijze waarop de auteur de problematiek van het onderwerp heeft benaderd en neergeschreven. De auteur respecteert daarbij het oorspronkelijke auteursrecht van de individueel geciteerde studies en eventueel bijhorende documentatie, zoals tabellen en figuren. DANKESWORT Diese Masterarbeit wäre nicht möglich gewesen ohne die Hilfe einiger wichtiger Personen, denen ich hier meinen Dank aussprechen möchte. In erster Linie möchte ich meiner Betreuerin Prof. dr. Carola Strobl herzlich für die wertvolle Hilfe und die unerschöpfliche Geduld danken, denn ohne sie hätte ich es einfach nicht schaffen können. Als ich über bestimmte Sachen zweifelte oder während des Prozesses auf Schwierigkeiten stieß, konnte ich sie immer einfach um Rat beten und mit einer schnellen Antwort rechnen. Auch die Termine im Laufe des Jahres habe ich als sehr angenehm und motivierend erfahren. -

Affective Polarization and Its Impact on College Campuses

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2020 Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses Sam Rosenblatt Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rosenblatt, Sam, "Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses" (2020). Honors Theses. 529. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/529 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN WE ALL JUST GET ALONG?: AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES by Sam Rosenblatt A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Political Science April 3, 2020 Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor: Chris Ellis _____________________________________ Department Chairperson: Scott Meinke Acknowledgements While the culmination of my honors thesis feels a bit anticlimactic as Bucknell has transitioned to remote education, I could not have accomplished this project without the help of the many faculty, friends, and family who supported me. To Professor Ellis, thank you for advising and guiding me throughout this process. Your advice was instrumental and I looked forward every week to discussing my progress and American politics with you. To Professor Meinke and Professor Stanciu, thank you for serving as additional readers. And especially to Professor Meinke for helping to spark my interest in politics during my freshman year. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

Gender Differences in Choice Shifts: a Study of Social Influence on Consumer Attitude Toward Food Irradiation Li-Jun Zhao Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 Gender differences in choice shifts: a study of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation Li-Jun Zhao Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Food Science Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Zhao, Li-Jun, "Gender differences in choice shifts: a tudys of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation" (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16783. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16783 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender differences in choice shifts: A study of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation by Li-jun Zhao A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Sociology Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1991 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ••• .1 Objectives. .2 CHAPTER I: LITERATURE REVIEW •••••.• .3 Theories of Choice Shifts ••••••• .3 Persuasive Arguments Theory ••••••• • ••••• 5 Social Comparison Theory •••• • ••••• 6 Self-Categorization Theory •• .8 Gender Differences in Choice Shifts. .9 Expectation states Theory •••••• • ••• 11 Gender Schema Theory ••••••••••. ...... 12 Gender Role strain ••••••••••••• . ....... 13 Other Correlates of Choice Shifts •• . ........ 14 Self-Esteem ••••••••••••••• .15 Self-Efficacy •••••••••••••••••• • •• 16 Locus of Control •••••••••••••••••••• . -

“We Are Coming for You Globalists!”

“We Are Coming For You Globalists!” Rhetorical Strategies of Online Conspiracy Communities in the USA ID: 1754351 SUPERVISOR: Dr. G.M. van Buuren NAME: Philipp Blaas SECOND READER: Prof. Dr. E. Bakker WORDS: 26.998 PROGRAM: MSc Crisis and Security Management DATE: June 8th, 2017 1 Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Defining Conspiracy ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Reality is Just a Matter of Perspective .................................................................................... 8 2.2.1. Social Constructivism ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2.2. Language versus Power in Political Discourse ................................................................. 10 2.3. The Threatening Other .......................................................................................................... 11 2.4. The Heroic ‘Us’ and the Evil ‘Them’ ................................................................................... 13 2.5. Rhetorical Strategies ............................................................................................................. 15 2.6. Populism: The Little Brother of Conspiracy