A Tale of Two Paranoids: a Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Accused of Pro-Roe Push Poll

MELVILLE CITY HEo RALD Volume 25 N 19 Melville City’s own INDEPENDENT newspaper li treet, remantle Saturday May 10, 2014 Leeming to Kardinya Edition - etterboed to eeming, ateman, ull ree, ardinya, h a www.fremantleherald.com/melvilles urdoh, urdoh niversity, illagee and inthrop *Fortnightly Email: [email protected] B ell tolls for etla d s by STEVE GRANT • Save Beeliar etlands members are reeling following speculation eeliar etlands says te bbott government is set to the arnett government should fund the construction of Roe 8 stop pushing oe until appeals by making it s first toll road against its environmental Teyre promising mass action to approval have been heard stop te proect Photo by Matthew heir all follows transport Dwyer minister ean alder onfirming he’s negotiating funding with the Find the Fake Ad & WIN a bbott government that would Chance for a Feast for 2 be tied to the highway slugging 42 Mews Rd, truies with ’s first toll road Fremantle (The Sunday Times, May 4, 2014). member andi hinna told the Herald her group was still trying For details, please see Competitions to digest the information, given premier olin arnett had said the Want good pay? Some easy, gentle long-planned etension through the exercise? Deliver the Herald to amsar-listed wetlands wouldn’t local letterboxes! It’s perfect for be built in this term of parliament all ages, from young teens to She says the announcement seniors looking to keep active. If maes a moery of government proesses, with appeals against you’re reliable we may just have the ’s environmental approval a round near you (we deliver of the road still to be heard. -

Telephone Calls and Text Messages in State Senate, District

STATE OF MAINE Commission Meeting 09/30/2020 COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENTAL ETHICS Agenda Item #5 AND ELECTION PRACTICES 135 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0135 To: Commission From: Michael Dunn, Esq., Political Committee Registrar Date: September 22, 2020 Re: Complaint against Public Opinion Research On September 15, 2020, the Commission received a complaint from the Lincoln County Democratic Committee (the “LCDC”) alleging that unknown persons acting under the name of Public Opinion Research have engaged in a “push poll” to influence the general election for State Senate, District #13. ETH 1-8. Voters have received phone calls from live callers asking questions that are likely designed to influence their vote and text messages linking to an online survey conducted through the SurveyMonkey.com containing similar questions. According to the LCDC, the organizers of the telephone campaign have violated three disclosure requirements in Maine Election Law: • the callers have not provided any “disclaimer statement” identifying who paid for the calls, • the calls do not meet special disclosure requirements applicable to push polls in Maine, and • no independent expenditure report has been filed relating to the calls, text messages, and online survey. The LCDC requests that the Commission initiate an investigation into these activities. The Commission staff has been unable to make contact with Public Opinion Research as part of our preliminary investigation. We cannot find an online presence for a polling or political consulting firm with that name. A “push poll” is a paid influence campaign conducted in the guise of a telephone survey. The telephone calls are designed to “push” the listener away from one candidate and towards another candidate. -

Group Support and Cognitive Dissonance 1 I'ma

Group support and cognitive dissonance 1 I‘m a Hypocrite, but so is Everyone Else: Group Support and the Reduction of Cognitive Dissonance Blake M. McKimmie, Deborah J. Terry, Michael A. Hogg School of Psychology, University of Queensland Antony S.R. Manstead, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam Running head: Group support and cognitive dissonance. Key words: cognitive dissonance, social identity, social support Contact: Blake McKimmie School of Psychology The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Phone: +61 7 3365-6406 Fax: +61 7 3365-4466 Group support and cognitive dissonance 2 [email protected] Abstract The impact of social support on dissonance arousal was investigated to determine whether subsequent attitude change is motivated by dissonance reduction needs. In addition, a social identity view of dissonance theory is proposed, augmenting current conceptualizations of dissonance theory by predicting when normative information will impact on dissonance arousal, and by indicating the availability of identity-related strategies of dissonance reduction. An experiment was conducted to induce feelings of hypocrisy under conditions of behavioral support or nonsupport. Group salience was either high or low, or individual identity was emphasized. As predicted, participants with no support from the salient ingroup exhibited the greatest need to reduce dissonance through attitude change and reduced levels of group identification. Results were interpreted in terms of self -

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated With

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated with the Bounded Confidence XY Model, Parameterized by Twitter Data Maksym Romenskyy Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK and Department of Mathematics, Uppsala University, Box 480, Uppsala 75106, Sweden Viktoria Spaiser School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Thomas Ihle Institute of Physics, University of Greifswald, Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 6, Greifswald 17489, Germany Vladimir Lobaskin School of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (Dated: July 26, 2018) Multiple countries have recently experienced extreme political polarization, which in some cases led to escalation of hate crime, violence and political instability. Beside the much discussed presi- dential elections in the United States and France, Britain’s Brexit vote and Turkish constitutional referendum, showed signs of extreme polarization. Among the countries affected, Ukraine faced some of the gravest consequences. In an attempt to understand the mechanisms of these phe- nomena, we here combine social media analysis with agent-based modeling of opinion dynamics, targeting Ukraine’s crisis of 2014. We use Twitter data to quantify changes in the opinion divide and parameterize an extended Bounded-Confidence XY Model, which provides a spatiotemporal description of the polarization dynamics. We demonstrate that the level of emotional intensity is a major driving force for polarization that can lead to a spontaneous onset of collective behavior at a certain degree of homophily and conformity. We find that the critical level of emotional intensity corresponds to a polarization transition, marked by a sudden increase in the degree of involvement and in the opinion bimodality. -

Ye Olde Publisher Vs. Mark Gerzon - Push Polls! Opinion Questions of the Day

• Letters: • L-Chastain chastizes Bag Ban People! • L-Ruemmler says Water District didn’t answer? • L-Luppens opine Eagle-Vail collapse imminent! • Avon & di Simone’s bag ban destroys freedom! Business Briefs – www.BusinessBriefs.net – Volume 10, Number 9 - July 27 thru Aug 30th, 2017 Distributed free online & to almost 900 locations in Vail, Beaver Creek & Eagle County, Colorado. 970-280-5555 . Injury Attorneys • Auto/Motorcycle • Ski/Snowboard • Dog Bites Rep. Diane Mitsch Bush • Other Injuries Free Consult broke a promise to serve! Percentage Fee Bloch & Chapleau 970.926.1700 Ye Olde Publisher vs. VailJustice.com Edwards/Denver Mark Gerzon - push polls! d, The Bad, The Ugly! The Goo • The Stupid: Most of the Avon Council - potted plants in street! • The Surprising: The amount of locals who don’t use VVMC! • The Defective Thinkers: Our elected Climate Change nutcases! • The Obfuscators: Dems afraid of illegal voting commission! lied to voters about ObamaCare! TraTcraec eT Tyyleer rA Agegnecy ncy • The Liars: Republicans who 97 Main9 7S Mtraeine Stt r•e eSt u! Situeit eW W-110066 ! •Ed wEadrwds,a CrOd s8,1 6C32O 81632 • They Don’t Care - 90% of Americans don’t care about Russia. 9P7h0o-n9e:2 967-04-932760-4 •37 0T !T Eymlaeirl:@ ttAylemrr@@Famamfam.c.coom m “We are proud to serve the Vail Valley providing the community with ““WWee arree prroudoud to servvee tthehe VVailail VValleyalley prroovvidingiding tthehe communittyy • Sad: The loss of Lew Meskiman, Ursula Fricker, Dick Blair! exwwitcitethhll eexxxcellentncellentt servi cseer avvicenicced pandro dpruroductoductcts ttsos mtoe meetet al lall y oyyouruourr ri insnsuurranceranceance needsneeds. -

Left-Wing Movements' Boom in Hungary

Left-wing movements’ boom in Hungary - Analysis of the situation of the Hungarian opposition - Tamás Boros – Arbeitspapier – Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Budapest Oktober 2012 Left-wing movements’ boom in Hungary - Analysis of the situation of the Hungarian opposition - Tamás Boros The Hungarian left-wing and liberal opposition faces an unprecedented situation: with the weakening of the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and the disappearance of its traditional coalition partner, the liberal Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ) in 2010, new parties and movements have started to rise in an effort to become inevitable politi- cal actors at the time of the next elections in 2014. The crucial question of the next two years is whether the Hungarian Socialist Party will be able to win the elections by itself, and, if not, whether an alliance of opposition movements can be created which will be able to defeat the current prime minister, Viktor Orbán. Between 1998 and 2010 a quasi two-party system characterised Hungary, where the Hungari- an Socialist Party and its liberal coalition partner faced off with the conservative Fidesz. The decision of the voters was as simple as choosing between the two sides – other parties, wheth- er brand new ones or ones with traditional ties, did not stand a reasonable chance of becoming a major political force in Hungary. By 2010, however, eight years spent in government had eroded the popularity of left-wing parties to such an extent that MSZP lost 60% of its former voters (1.4 million people) and SZDSZ all but disappeared from the political map of Hungary. -

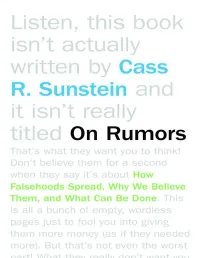

On Rumors Also by Cass R

On Rumors Also by Cass R. Sunstein Simpler: The Future of Government Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard Thaler) Worst-Case Scenarios Republic.com 2.0 Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge The Second Bill of Rights: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle Why Societies Need Dissent Risk and Reason: Safety, Law, and the Environment One Case at a Time Free Markets and Social Justice Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict Democracy and the Problem of Free Speech The Partial Constitution After the Rights Revolution On Rumors How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done Cass R. Sunstein With a new afterword by the author Princeton University Press • Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2014 by Cass R. Sunstein Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Originally published in North America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2009 First Princeton Edition 2014 ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-16250-8 LCCN 2013950544 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper. -

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration Marina Lindell (Åbo Akademi University), André Bächtiger (University of Stuttgart), Kimmo Grönlund (Åbo Akademi University), Kaisa Herne (University of Tampere), Maija Setälä (University of Turku) Abstract In the study of deliberation, a largely underexplored area is why some participants become more extreme, whereas some become more moderate. Opinion polarization is usually considered a suspicious outcome of deliberation, while moderation is seen as a desirable one. This article takes issue with this view. Results from a deliberative experiment on immigration show that polarizers and moderators were not different in their socio-economic, cognitive, or affective profiles. Moreover, both polarization and moderation can entail deliberatively desired pathways: in the experiment, both polarizers and moderators learned during deliberation, levels of empathy were fairly high on both sides, and group pressures barely mattered. Finally, the absence of a participant with an immigrant background in a group was associated with polarization in anti-immigrant direction, bolstering longstanding claims regarding the importance of presence in interaction (Philips 1995). Paper presented at the “13ème Congrès National Association Française de Science Politique (AFSP), Aix-en-Provence, June 22–24, 2015 1 Introduction Empirical studies of citizen deliberation suggest that participants often change opinions (and also quite radically; see, e.g., Fishkin, 2009). Luskin et al. (2002) claim that knowledge gain is an important mechanism of opinion change, whereas Sanders (2012) was unable to identify any robust predictor of opinion change in a recent study based on a pan-European deliberative poll (Europolis). A largely understudied area in this regard is why some participants polarize their opinions due to deliberation, and why others moderate them. -

Affective Polarization and Its Impact on College Campuses

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2020 Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses Sam Rosenblatt Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rosenblatt, Sam, "Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses" (2020). Honors Theses. 529. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/529 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN WE ALL JUST GET ALONG?: AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES by Sam Rosenblatt A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Political Science April 3, 2020 Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor: Chris Ellis _____________________________________ Department Chairperson: Scott Meinke Acknowledgements While the culmination of my honors thesis feels a bit anticlimactic as Bucknell has transitioned to remote education, I could not have accomplished this project without the help of the many faculty, friends, and family who supported me. To Professor Ellis, thank you for advising and guiding me throughout this process. Your advice was instrumental and I looked forward every week to discussing my progress and American politics with you. To Professor Meinke and Professor Stanciu, thank you for serving as additional readers. And especially to Professor Meinke for helping to spark my interest in politics during my freshman year. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

Actualities and Electronic Press Kits, 40, 85, 122 Advertising, Radio

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. Howard Index More Information Index actualities and electronic press kits, campaigns: candidate type, 145; 40, 85, 122 grassroots or social movement advertising, radio, television, and type, 144; implanted or Astroturf Web site, 88–94 type, 98, 145, 177; lobby group affinity networks, 85, 139, 144–147, type, 144. See also hypermedia 158 campaigns; issue campaigns; mass AFL-CIO, 6, 138 media campaigns; presidential Agora, GrassrootsActivist.org, 120 campaigns America Coming Together (ACT), 18 CandidateShopper, Voting.com, 113 American Association of Retired capo managers, 148 Persons (AARP), 137, 160 categorization: and identity, 37, 183, American Civil Liberties Union 188; as political negotiation, (ACLU), 137 133–134, 141; managed paradoxes, Amnesty International, 84, 85 86, 154, 157 astroturf or implanted campaign. chat and listservs, 112, 239 See campaigns ChoicePoint Technologies, 15 Astroturf Compiler Software, citizenship: historical context, 185; Astroturf-Lobby.org, 86 privatized, 189–190; shadow, Astroturf-Lobby.org, 83–100, 187–189; thin, 185–187 175–176 coding generals, 148 avatars, 116, 174 Columbia School. See Lazarsfeld, Paul; Merton, Robert Barber, Benjamin, 102, 149 conferences and conventions: Baudrillard, Jean, 67 Democratic and Republican blogging, 16, 121, 239 National Convention, 35, 72, 85, Bourdieu, Pierre, 69, 70, 212 166; and group identity, 34–36, 50 cookie, 239–240 campaign managers. See political C-SPAN, 65 consultants cultural frame, 67, 172, 205. See also campaign spending, 91, 146 media effects 261 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. -

The Year of Rearrangement

The Year of Rearrangement The Populist Right and the Far-Right in Contemporary Hungary The Year of Rearrangement The Populist Right and the Far-Right in Contemporary Hungary Authors: Attila Juhász Bulcsú Hunyadi Edited by: Eszter Galgóczi Attila Juhász Dániel Róna Patrik Szicherle Edit Zgut This study was prepared within the framework of the project “Strategies against the Far-Right”, in cooperation with the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung e.V., in 2017. Table of Contens The opinions expressed in the study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. Introduction ___________________________________________________________________ 7 Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________ 9 Political Environment __________________________________________________________ 12 Competing for Votes: The Voters of Fidesz and Jobbik ____________________________ 19 Socio-Demographic Composition ______________________________________________ 20 Political Preferences __________________________________________________________ 25 Election Chances ____________________________________________________________ 31 Competition on the Far End: The Extremist Rhetoric of Fidesz and Jobbiki __________32 Anti-Immigration Sentiments ___________________________________________________ 32 Anti-Semitism _______________________________________________________________ 41 Anti-Gypsyism ______________________________________________________________45 Homophobia ________________________________________________________________46