Deliberative Trouble? Why Groups Go to Extremes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Group Support and Cognitive Dissonance 1 I'ma

Group support and cognitive dissonance 1 I‘m a Hypocrite, but so is Everyone Else: Group Support and the Reduction of Cognitive Dissonance Blake M. McKimmie, Deborah J. Terry, Michael A. Hogg School of Psychology, University of Queensland Antony S.R. Manstead, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam Running head: Group support and cognitive dissonance. Key words: cognitive dissonance, social identity, social support Contact: Blake McKimmie School of Psychology The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Phone: +61 7 3365-6406 Fax: +61 7 3365-4466 Group support and cognitive dissonance 2 [email protected] Abstract The impact of social support on dissonance arousal was investigated to determine whether subsequent attitude change is motivated by dissonance reduction needs. In addition, a social identity view of dissonance theory is proposed, augmenting current conceptualizations of dissonance theory by predicting when normative information will impact on dissonance arousal, and by indicating the availability of identity-related strategies of dissonance reduction. An experiment was conducted to induce feelings of hypocrisy under conditions of behavioral support or nonsupport. Group salience was either high or low, or individual identity was emphasized. As predicted, participants with no support from the salient ingroup exhibited the greatest need to reduce dissonance through attitude change and reduced levels of group identification. Results were interpreted in terms of self -

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated With

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated with the Bounded Confidence XY Model, Parameterized by Twitter Data Maksym Romenskyy Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK and Department of Mathematics, Uppsala University, Box 480, Uppsala 75106, Sweden Viktoria Spaiser School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Thomas Ihle Institute of Physics, University of Greifswald, Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 6, Greifswald 17489, Germany Vladimir Lobaskin School of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (Dated: July 26, 2018) Multiple countries have recently experienced extreme political polarization, which in some cases led to escalation of hate crime, violence and political instability. Beside the much discussed presi- dential elections in the United States and France, Britain’s Brexit vote and Turkish constitutional referendum, showed signs of extreme polarization. Among the countries affected, Ukraine faced some of the gravest consequences. In an attempt to understand the mechanisms of these phe- nomena, we here combine social media analysis with agent-based modeling of opinion dynamics, targeting Ukraine’s crisis of 2014. We use Twitter data to quantify changes in the opinion divide and parameterize an extended Bounded-Confidence XY Model, which provides a spatiotemporal description of the polarization dynamics. We demonstrate that the level of emotional intensity is a major driving force for polarization that can lead to a spontaneous onset of collective behavior at a certain degree of homophily and conformity. We find that the critical level of emotional intensity corresponds to a polarization transition, marked by a sudden increase in the degree of involvement and in the opinion bimodality. -

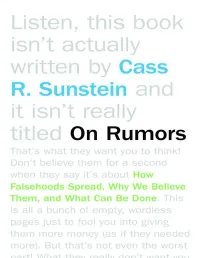

On Rumors Also by Cass R

On Rumors Also by Cass R. Sunstein Simpler: The Future of Government Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard Thaler) Worst-Case Scenarios Republic.com 2.0 Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge The Second Bill of Rights: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle Why Societies Need Dissent Risk and Reason: Safety, Law, and the Environment One Case at a Time Free Markets and Social Justice Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict Democracy and the Problem of Free Speech The Partial Constitution After the Rights Revolution On Rumors How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done Cass R. Sunstein With a new afterword by the author Princeton University Press • Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2014 by Cass R. Sunstein Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Originally published in North America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2009 First Princeton Edition 2014 ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-16250-8 LCCN 2013950544 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper. -

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration Marina Lindell (Åbo Akademi University), André Bächtiger (University of Stuttgart), Kimmo Grönlund (Åbo Akademi University), Kaisa Herne (University of Tampere), Maija Setälä (University of Turku) Abstract In the study of deliberation, a largely underexplored area is why some participants become more extreme, whereas some become more moderate. Opinion polarization is usually considered a suspicious outcome of deliberation, while moderation is seen as a desirable one. This article takes issue with this view. Results from a deliberative experiment on immigration show that polarizers and moderators were not different in their socio-economic, cognitive, or affective profiles. Moreover, both polarization and moderation can entail deliberatively desired pathways: in the experiment, both polarizers and moderators learned during deliberation, levels of empathy were fairly high on both sides, and group pressures barely mattered. Finally, the absence of a participant with an immigrant background in a group was associated with polarization in anti-immigrant direction, bolstering longstanding claims regarding the importance of presence in interaction (Philips 1995). Paper presented at the “13ème Congrès National Association Française de Science Politique (AFSP), Aix-en-Provence, June 22–24, 2015 1 Introduction Empirical studies of citizen deliberation suggest that participants often change opinions (and also quite radically; see, e.g., Fishkin, 2009). Luskin et al. (2002) claim that knowledge gain is an important mechanism of opinion change, whereas Sanders (2012) was unable to identify any robust predictor of opinion change in a recent study based on a pan-European deliberative poll (Europolis). A largely understudied area in this regard is why some participants polarize their opinions due to deliberation, and why others moderate them. -

Affective Polarization and Its Impact on College Campuses

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2020 Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses Sam Rosenblatt Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rosenblatt, Sam, "Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses" (2020). Honors Theses. 529. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/529 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN WE ALL JUST GET ALONG?: AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES by Sam Rosenblatt A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Political Science April 3, 2020 Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor: Chris Ellis _____________________________________ Department Chairperson: Scott Meinke Acknowledgements While the culmination of my honors thesis feels a bit anticlimactic as Bucknell has transitioned to remote education, I could not have accomplished this project without the help of the many faculty, friends, and family who supported me. To Professor Ellis, thank you for advising and guiding me throughout this process. Your advice was instrumental and I looked forward every week to discussing my progress and American politics with you. To Professor Meinke and Professor Stanciu, thank you for serving as additional readers. And especially to Professor Meinke for helping to spark my interest in politics during my freshman year. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

Gender Differences in Choice Shifts: a Study of Social Influence on Consumer Attitude Toward Food Irradiation Li-Jun Zhao Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 Gender differences in choice shifts: a study of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation Li-Jun Zhao Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Food Science Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Zhao, Li-Jun, "Gender differences in choice shifts: a tudys of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation" (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 16783. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/16783 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender differences in choice shifts: A study of social influence on consumer attitude toward food irradiation by Li-jun Zhao A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Sociology Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1991 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION ••• .1 Objectives. .2 CHAPTER I: LITERATURE REVIEW •••••.• .3 Theories of Choice Shifts ••••••• .3 Persuasive Arguments Theory ••••••• • ••••• 5 Social Comparison Theory •••• • ••••• 6 Self-Categorization Theory •• .8 Gender Differences in Choice Shifts. .9 Expectation states Theory •••••• • ••• 11 Gender Schema Theory ••••••••••. ...... 12 Gender Role strain ••••••••••••• . ....... 13 Other Correlates of Choice Shifts •• . ........ 14 Self-Esteem ••••••••••••••• .15 Self-Efficacy •••••••••••••••••• • •• 16 Locus of Control •••••••••••••••••••• . -

“We Are Coming for You Globalists!”

“We Are Coming For You Globalists!” Rhetorical Strategies of Online Conspiracy Communities in the USA ID: 1754351 SUPERVISOR: Dr. G.M. van Buuren NAME: Philipp Blaas SECOND READER: Prof. Dr. E. Bakker WORDS: 26.998 PROGRAM: MSc Crisis and Security Management DATE: June 8th, 2017 1 Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Theoretical Framework ................................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Defining Conspiracy ............................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Reality is Just a Matter of Perspective .................................................................................... 8 2.2.1. Social Constructivism ......................................................................................................... 9 2.2.2. Language versus Power in Political Discourse ................................................................. 10 2.3. The Threatening Other .......................................................................................................... 11 2.4. The Heroic ‘Us’ and the Evil ‘Them’ ................................................................................... 13 2.5. Rhetorical Strategies ............................................................................................................. 15 2.6. Populism: The Little Brother of Conspiracy -

A Tale of Two Paranoids: a Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 1 Number 2 Secrecy and Authoritarianism Article 3 February 2018 A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Andria Timmer Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Joseph Sery Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Sean Thomas Connable Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Jennifer Billinson Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Timmer, Andria; Joseph Sery; Sean Thomas Connable; and Jennifer Billinson. 2018. "A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán." Secrecy and Society 1(2). https://doi.org/10.31979/ 2377-6188.2018.010203 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Abstract Within the last decade, a rising tide of right-wing populism across the globe has inspired a renewed push toward nationalism. -

Bias and Affective Polarization

Bias and Affective Polarization Daniel F. Stone Bowdoin College September 2016∗ Abstract I propose a model of affective polarization (\that both Republicans and Democrats increasingly dislike, even loathe, their opponents," Iyengar et al, 2012). In the model, two agents repeatedly choose actions based on private interests, the social good, their own \character" (willingness to trade private for social gains) and beliefs about the other agent's character. Each agent could represent a political party, or the model could apply to other settings, such as spouses or business partners. Each agent Bayesian updates beliefs about the other's character, and dislikes the other more when its character is perceived as more self-serving. I characterize the dynamic and long-run effects of three biases: a prior bias against the other agent's character, the false consensus bias, and limited strategic thinking. Prior bias against the opponent remains constant or dissipates over time, and actions do not diverge. By contrast, the other two biases, which are not directly related to character, cause actions to become more extreme over time and repeatedly be \worse" than expected, causing affective polarization|even when both players are arbitrarily \good" (unselfish). For some parameter values, long-run affective polarization is unbounded, despite Bayesian updating. The results imply that affective polarization can be caused by cognitive bias, and that subtlety and unawareness of bias are key forces driving greater severity of this type of polarization. Keywords: affective polarization, partyism, polarization, disagreement, dislike, over-precision, unawareness, media bias JEL codes: D72; D83 ∗I thank Steven J. Miller, Dan Wood, Gaurav Sood, Dan Kahan, Roland B´enabou, Andrei Shleifer, and participants at seminars at the University of Western Ontario, Wake Forest University and Southern Methodist University, in particular Saltuk Ozerturk, Tim Salmon, Bo Chen, James Lake, Al Slivinski, Greg Pavlov, and Charles Zheng, for helpful comments and discussion. -

Cass Sunstein on Group Polarization and Cyber-Cascades

Cass Sunstein on Group Polarization and Cyber-Cascades An excerpt from “The Daily We”, which appeared in the Boston Review, Summer 2001 Specialization and Fragmentation In a system with public forums and general interest intermediaries, people will frequently come across materials that they would not have chosen in advance—and in a diverse society, this provides something like a common framework for social experience. A fragmented communications market will change things significantly. Consider some simple facts. If you take the ten most highly rated television programs for whites, and then take the ten most highly rated programs for African Americans, you will find little overlap between them. Indeed, more than half of the ten most highly rated programs for African Americans rank among the ten least popular programs for whites. With respect to race, similar divisions can be found on the Internet. Not surprisingly, many people tend to choose like-minded sites and like-minded discussion groups. Many of those with committed views on a topic—gun control, abortion, affirmative action—speak mostly with each other. It is exceedingly rare for a site with an identifiable point of view to provide links to sites with opposing views; but it is very common for such a site to provide links to like-minded sites. With a dramatic increase in options, and a greater power to customize, comes an increase in the range of actual choices. Those choices are likely, in many cases, to mean that people will try to find material that makes them feel comfortable, or that is created by and for people like themselves. -

Online Islamophobia After the Brussels Attacks on March 22Nd 2016

Master Thesis MSc in Sociology: track migration and ethnic studies Online Islamophobia after the Brussels attacks on March 22nd 2016. A critical discourse analysis of Facebook comments on news articles regarding the Brussels attacks by Het Laatste Nieuws and De Standaard Ezra Dupré (ID: 12759317) Supervisor: dr. L.M. Hernandez Aguilar Second reader: dr. M.A. van den Berg July 6th 2020 Abstract Online Islamophobia in the Flemish context is facing a research gap. Offline Flemish Islamophobia has been investigated previously. However a significant amount of reports on Belgian Islamophobic behaviour took place online. Social network platforms have become full- fledged social spheres where public discourse debates are encouraged. This thesis investigates the dominant narratives of Islamophobic comments on Flemish news articles posted on Facebook within a month after the Brussels bombing on March 22nd 2016. Because of the cultural and linguistic differences between the French speaking community and Flemish speaking community in Belgium, Islamophobia is bound to be affected by these differences. The comments are posted as a response to articles by the Flemish popular newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws and the Flemish quality newspaper De Standaard. In total 28 416 comments were analysed through Fairclough's critical discourse analysis with an additional focus on semiotic decisions made in the comments. The results indicate that dominant narratives of offline Islamophobic statements conform to online dominant narratives found in the Facebook comments. Dominant narratives supplementary to previously examined offline dominant narratives were detected such as “Muslims do not provide adequate upbringings for their children.” The main Islamophobic themes discussed in the comments cohere and overlap.