UNIVERSAL SCALE FORMS for GUITAR from INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC Robert Schneider

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Hindustani Name Chakra Sa C

The Indian Scale & Comparison with Western Staff Notations: The vowel 'a' is pronounced as 'a' in 'father', the vowel 'i' as 'ee' in 'feet', in the Sa-Ri-Ga Scale In this scale, a high note (swara) will be indicated by a dot over it and a note in the lower octave will be indicated by a dot under it. Hindustani Chakra Note Staff Symbol Carnatic Name Name MulAadhar Sa C - Natural Shadaj Shadaj (Base of spine) Shuddha Swadhishthan ri D - flat Komal ri Rishabh (Genitals) Chatushruti Ri D - Natural Shudhh Ri Rishabh Sadharana Manipur ga E - Flat Komal ga Gandhara (Navel & Solar Antara Plexus) Ga E - Natural Shudhh Ga Gandhara Shudhh Shudhh Anahat Ma F - Natural Madhyam Madhyam (Heart) Tivra ma F - Sharp Prati Madhyam Madhyam Vishudhh Pa G - Natural Panchama Panchama (Throat) Shuddha Ajna dha A - Flat Komal Dhaivat Dhaivata (Third eye) Chatushruti Shudhh Dha A - Natural Dhaivata Dhaivat ni B - Flat Kaisiki Nishada Komal Nishad Sahsaar Ni B - Natural Kakali Nishada Shudhh Nishad (Crown of head) Så C - Natural Shadaja Shadaj Property of www.SarodSitar.com Copyright © 2010 Not to be copied or shared without permission. Short description of Few Popular Raags :: Sanskrut (Sanskrit) pronunciation is Raag and NOT Raga (Alphabetical) Aroha Timing Name of Raag (Karnataki Details Avroha Resemblance) Mood Vadi, Samvadi (Main Swaras) It is a old raag obtained by the combination of two raags, Ahiri Sa ri Ga Ma Pa Ga Ma Dha ni Så Ahir Bhairav Morning & Bhairav. It belongs to the Bhairav Thaat. Its first part (poorvang) has the Bhairav ang and the second part has kafi or Så ni Dha Pa Ma Ga ri Sa (Chakravaka) serious, devotional harpriya ang. -

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian

Fusion Without Confusion Raga Basics Indian Rhythm Basics Solkattu, also known as konnakol is the art of performing percussion syllables vocally. It comes from the Carnatic music tradition of South India and is mostly used in conjunction with instrumental music and dance instruction, although it has been widely adopted throughout the world as a modern composition and performance tool. Similarly, the music of North India has its own system of rhythm vocalization that is based on Bols, which are the vocalization of specific sounds that correspond to specific sounds that are made on the drums of North India, most notably the Tabla drums. Like in the south, the bols are used in musical training, as well as composition and performance. In addition, solkattu sounds are often referred to as bols, and the practice of reciting bols in the north is sometimes referred to as solkattu, so the distinction between the two practices is blurred a bit. The exercises and compositions we will discuss contain bols that are found in both North and South India, however they come from the tradition of the North Indian tabla drums. Furthermore, the theoretical aspect of the compositions is distinctly from the Hindustani, (north Indian) tradition. Hence, for the purpose of this presentation, the use of the term Solkattu refers to the broader, more general practice of Indian rhythmic language. South Indian Percussion Mridangam Dolak Kanjira Gattam North Indian Percussion Tabla Baya (a.k.a. Tabla) Pakhawaj Indian Rhythm Terms Tal (also tala, taal, or taala) – The Indian system of rhythm. Tal literally means "clap". -

Hindustani Classic Music

HINDUSTANI CLASSIC MUSIC: Junior Grade or Prathamik : Syllabus : No theory exam in this grade Swarajnana Talajnana essential Ragajnana Practicals: 1. Beginning of swarabyasa - in three layas 2. 2 Swaramalikas 5 Lakshnageete Chotakyal Alap - 4 ragas Than - 4 Drupad - should be practiced 3. Bhajan - Vachana - Dasapadas 4. Theental, Dadara, Ektal (Dhruth), Chontal, Juptal, Kheruva Talu - Sam-Pet-Husi-Matras - should practice Tekav. 5. Swarajnana 6. Knowledge of the words - nada, shruthi, Aroha, Avaroha, Vadi - Samvedi, Komal - Theevra - Shuddha - Sasthak - Ganasamay - Thaat - Varjya. 7. Swaralipi - should be learnt. Senior Grade: (Madhyamik) Syllabus : Theory: 1. Paribhashika words 2. Sound & place of emergence of sound 3. The practice of different ragas out of “thaat” - based on Pandith Venkatamukhi Mela System 4. To practice ragalaskhanas of different ragas 5. Different Talas - 9 (Trital, Dadra, Jup, Kherva, Chantal, Tilawad, Roopak, Damar, Deepchandi) explanation of talas with Tekas. 6. Chotakhyal, Badakhyal, Bhajan, Tumari, Geethprakaras - Lakshanas. 7. Life history of Jayadev, Sarangdev, Surdas, Purandaradas, Tansen, Akkamahadevi, Sadarang, Kabeer, Meera, Haridas. 8. Knowledge of musical instrument Practicals: 1. Among 20 ragas - Chotakhyal in each 2. Badakhyal - for 10 ragas (Bhoopali, Yamani, Bheempalas, Bageshree, Malkonnse, Alhaiah Bilawal, Bahar, Kedar, Poorvi, Shankara. 3. Learn to sing one drupad in Tay, Dugun & Changun - one Damargeete. VIDHWAN PROFICIENCY Syllabus: Theory 1. Paribhashika Shabdas. 2. 7 types of Talas - their parts (angas) 3. Tabala bol - Tala Jnana, Vilambitha Ektal, Jumra, Adachontal, Savari, Panjabi, Tappa. 4. Raga lakshanas of Bhairav, Shuddha Sarang, Peelu, Multhani, Sindura, Adanna, Jogiya, Hamsadhwani, Gandamalhara, Ragashree, Darbari, Kannada, Basanthi, Ahirbhairav, Todi etc., Alap, Swaravisthara, Sama Prakruthi, Ragas criticism, Gana samay - should be known. -

Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men

Volume 64, Issue 1, 2020 Journal of Scientific Research Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. Evaluation of the Effects of Music Therapy Using Todi Raga of Hindustani Classical Music on Blood Pressure, Pulse Rate and Respiratory Rate of Healthy Elderly Men Samarpita Chatterjee (Mukherjee) 1, and Roan Mukherjee2* 1 Department of Hindustani Classical Music (Vocal), Sangit-Bhavana, Visva-Bharati (A Central University), Santiniketan, Birbhum-731235,West Bengal, India 2 Department of Human Physiology, Hazaribag College of Dental Sciences and Hospital, Demotand, Hazaribag 825301, Jharkhand, India. [email protected] Abstract Several studies have indicated that music therapy may affect I. INTRODUCTION cardiovascular health; in particular, it may bring positive changes Music may be regarded as the projection of ideas as well as in blood pressure levels and heart rate, thereby improving the emotions through significant sounds produced by an instrument, overall quality of life. Hence, to regulate blood pressure, music voices, or both by taking into consideration different elements of therapy may be regarded as a significant complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). The respiratory rate, if maintained melody, rhythm, and harmony. Music plays an important role in within the normal range, may promote good cardiac health. The everyone’s life. Music has the power to make one experience aim of the present study was to evaluate the changes in blood harmony, emotional ecstasy, spiritual uplifting, positive pressure, pulse rate and respiratory rate in healthy and disease-free behavioral changes, and absolute tranquility. The annoyance in males (age 50-60 years), at the completion of 30 days of music life may increase in lack of melody and harmony. -

Ragang Based Raga Identification System

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 16, Issue 3 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 83-85 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Ragang based Raga Identification system Awadhesh Pratap Singh Tomer Assistant Professor (Music-vocal), Department of Music Dr. H. S. G. Central University Sagar M.P. Gopal Sangeet Mahavidhyalaya Mahaveer Chowk Bina Distt. Sagar (M.P.) 470113 Abstract: The paper describes the importance of Ragang in the Raga classification system and its utility as being unique musical patterns; in raga identification. The idea behind the paper is to reinvestigate Ragang with a prospective to use it in digital classification and identification system. Previous works in this field are based on Swara sequence and patterns, Pakad and basic structure of Raga individually. To my best knowledge previous works doesn’t deal with the Ragang Patterns for identification and thus the paper approaches Raga identification with a Ragang (musical pattern group) base model. This work also reviews the Thaat-Raagang classification system. This describes scope in application for Automatic digital teaching of classical music by software program to analyze music (Classical vocal and instrumental). The Raag classification should be flawless and logically perfect for best ever results. Key words: Aadhar shadaj, Ati Komal Gandhar , Bahar, Bhairav, Dhanashri, Dhaivat, Gamak, Gandhar, Gitkarri, Graam, Jati Gayan, Kafi, Kanada, Kann, Komal Rishabh , Madhyam, Malhar, Meed, Nishad, Raga, Ragang, Ragini, Rishabh, Saarang, Saptak, Shruti, Shrutiantra, Swaras, Swar Prastar, Thaat, Tivra swar, UpRag, Vikrat Swar A Raga is a tonal frame work for composition and improvisation. It embodies a unique musical idea.(Balle and Joshi 2009, 1) Ragang is included in 10 point Raga classification of Saarang Dev, With Graam Raga, UpRaga and more. -

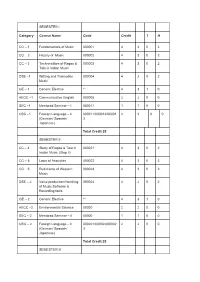

1 Fundamentals of Music 000001 4 3 0 2 CC

SEMESTER I Category Course Name Code Credit T H CC – 1 Fundamentals of Music 000001 4 3 0 2 CC – 2 History of Music 000002 4 3 0 2 CC – 3 Technicalities of Ragas & 000003 4 3 0 2 Tala in Indian Music DSE –1 Writing and Transcribe 000004 4 2 0 2 Music GE – 1 Generic Elective ** 4 3 1 0 AECC –1 Communicative English 000005 2 2 0 0 SEC –1 Mentored Seminar – I 000011 1 1 0 0 USC –1 Foreign Language – II 000011/000012/00001 2 2 0 0 (German/ Spanish/ 3 Japanese) Total Credit 25 SEMESTER II CC – 4 Study of Ragas & Tala in 000021 4 3 0 2 Indian Music (Step ii) CC – 5 Laws of Acoustics 000022 4 3 0 2 CC – 6 Rudiments of Western 000023 4 3 0 2 Music DSE – 2 Voice production/Handling 000024 4 2 0 2 of Music Software & Recording tools GE – 2 Generic Elective ** 4 3 1 0 AECC –2 Environmental Science 00000 2 2 0 0 SEC – 2 Mentored Seminar – II 00000 1 1 0 0 USC – 2 Foreign Language – II 000021/000022/00002 2 2 0 0 (German/ Spanish/ 3 Japanese) Total Credit 25 SEMESTER III CC – 7 Introduction to 000001 4 4 0 4 Contemporary Music CC – 8 Study of the Compositions 000002 5 3 0 2 of Tagore and other composers CC – 9 Audio and Sheet Music 000003 2 0 0 2 Discussion & Review CC – 10 Study on Theater Arts 000004 3 0 0 2 CC – 11 Study on Dance Arts 000005 3 4 0 4 DSE – 3 Film Music Appreciation & 000006 3 2 1 0 Review GE – 3 Generic Elective ** 4 3 1 0 SEC – 3 Mentored Seminar – III 000001 1 1 0 0 Total Credit 25 SEMESTER IV CC – 12 Demonstration of Ragas & 000011 4 3 1 0 Tala in Indian Music (Step iii) CC – 13 Mathematics of Music 000012 4 3 1 0 CC – 14 Overview -

The Thaat-Ragas of North Indian Classical Music: the Basic Atempt to Perform Dr

The Thaat-Ragas of North Indian Classical Music: The Basic Atempt to Perform Dr. Sujata Roy Manna ABSTRACT Indian classical music is divided into two streams, Hindustani music and Carnatic music. Though the rules and regulations of the Indian Shastras provide both bindings and liberties for the musicians, one can use one’s innovations while performing. As the Indian music requires to be learnt under the guidance of Master or Guru, scriptural guidelines are never sufficient for a learner. Keywords: Raga, Thaat, Music, Performing, Alapa. There are two streams of Classical music of India – the Ragas are to be performed with the basic help the North Indian i.e., Hindustani music and the of their Thaats. Hence, we may compare the Thaats South Indian i.e., Carnatic music. The vast area of with the skeleton of creature, whereas the body Indian Classical music consists upon the foremost can be compared with the Raga. The names of the criterion – the origin of the Ragas, named the 10 (ten) Thaats of North Indian Classical Music Thaats. In the Carnatic system, there are 10 system i.e., Hindustani music are as follows: Thaats. Let us look upon the origin of the 10 Thaats Sl. Thaats Ragas as well as their Thaat-ragas (i.e., the Ragas named 01. Vilabal Vilabal, Alhaiya–Vilaval, Bihag, according to their origin). The Indian Shastras Durga, Deshkar, Shankara etc. 02. Kalyan Yaman, Bhupali, Hameer, Kedar, throw light on the rules and regulations, the nature Kamod etc. of Ragas, process of performing these, and the 03. Khamaj Khamaj, Desh, Tilakkamod, Tilang, liberty and bindings of the Ragas while Jayjayanti / Jayjayvanti etc. -

প্রভাত সঙ্গীত Prabhat Samgiita

Intensive Training of Devotional Songs প্রভাত সঙ্গীত Prabhat Samgiita with Kirit Dave, Ashesh, and Jiivanii July 13 to 21, 2015 Espaço Anirvana, Pontal do Paraná – PR Prabhat Samgiita Tour Brazil 2015 July 10 to August 09 Porto Alegre – RS :: July 10 to 12 – workshop and recital – with Kirit Pontal do Sul – PR :: July 13 to 21 – Prabhat Samgiita intensive training – with Kirit, Ashesh and Jiivanii Pontal do Sul – PR :: July 22 and 23 –tabla training – with Ashesh Chapecó – SC :: July 22 and 23 – presentation on meditation – with Kirit Curitiba – PR :: July 24 – recital – with Kirit Ananda Kiirtana / Belmiro Braga – MG :: July 25 to 27 – workshops during and after retreat – with Kirit Brasília – DF :: July 31 to August 02 – workshop and recital – with Kirit Rio de Janeiro – RJ :: August 07 to 09 – workshop and recital – with Kirit ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Organizing Committee of 2015 Tour Coordinator: Mahesh Counselor: Kirit Local Organizers: Jyotiprakash e Parabhakti – Porto Alegre Tannistha – Pontal do Sul Ishthi e Ruchiira – Chapecó Vishvanath – Curitiba Vimala – Ananda Kiirtana Manorainjan e Dada Japeshvarananda – Brasília Nirmegha – Rio de Janeiro Volunteers of Intensive Training: Kirit – Teacher and Counselor Mahesh – Coordinator Ragamayii – Translator Jiivanii – PS teacher Tannistha and Ratna – Organizers Ashesh – Tabla player and trainer Front page art: Jiivanii 2 INDEX INTRODUCTION TO PRABHAT SAMGIIT .............................................................................. 4 PRONUNCIATION AND LANGUAGE SYNTAX ..................................................................... -

Raga (Melodic Mode) Raga This Article Is About Melodic Modes in Indian Music

FREE SAMPLES FREE VST RESOURCES EFFECTS BLOG VIRTUAL INSTRUMENTS Raga (Melodic Mode) Raga This article is about melodic modes in Indian music. For subgenre of reggae music, see Ragga. For similar terms, see Ragini (actress), Raga (disambiguation), and Ragam (disambiguation). A Raga performance at Collège des Bernardins, France Indian classical music Carnatic music · Hindustani music · Concepts Shruti · Svara · Alankara · Raga · Rasa · Tala · A Raga (IAST: rāga), Raag or Ragam, literally means "coloring, tingeing, dyeing".[1][2] The term also refers to a concept close to melodic mode in Indian classical music.[3] Raga is a remarkable and central feature of classical Indian music tradition, but has no direct translation to concepts in the classical European music tradition.[4][5] Each raga is an array of melodic structures with musical motifs, considered in the Indian tradition to have the ability to "color the mind" and affect the emotions of the audience.[1][2][5] A raga consists of at least five notes, and each raga provides the musician with a musical framework.[3][6][7] The specific notes within a raga can be reordered and improvised by the musician, but a specific raga is either ascending or descending. Each raga has an emotional significance and symbolic associations such as with season, time and mood.[3] The raga is considered a means in Indian musical tradition to evoke certain feelings in an audience. Hundreds of raga are recognized in the classical Indian tradition, of which about 30 are common.[3][7] Each raga, state Dorothea -

2. Ijhss-Exploring Symbolism of Ragas on Costume and Designing Contemporary Wear

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN(P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 7, Issue 5, Aug - Sep 2018; 11-26 © IASET EXPLORING SYMBOLISM OF RAGAS ON COSTUME AND DESIGNING CONTEMPORARY WEAR Vaishali Menon 1 & Kauvery Bai 2 1Research Scholar, Department of Textiles and Clothing, Bangalore, Karnataka, India 2Associate Professor, Department of Textiles and Clothing, Smt VHD Central Institute of Home Science, Bangalore, Karnataka, India ABSTRACT Indian classical music is one of the ancient art forms in the world. Apart from being deeply spiritual, it also offers a rich visual and cultural experience. Ragas are an integral part of Indian classical music which is a set of minimum 5 notes set in a certain progression with emphasis on certain notes, creating a specific mood or depicting certain emotions which are largely associated with the time and season in which they are sung, Character of the notes and dominant notes in a Raga. This study was undertaken to explore the symbolism of 6 principle ragas associated with 6 different seasons in nature. Symbolism was studied for Seasons, emotions, time and color associated with Raga Bhairav, Megh, Malkauns, Hindol, Shree, and Deepak. This symbolism was correlated with costumes to design contemporary garments, using Indian fabrics like Ikkat, Kalamkari, Ahimsa Silk, Chiffon, Batik etc. These were further analyzed by musicians, students and faculty in the fashion field. From this study, it was found that there is the association between the nature of Raga and mood created by the same. The creative process of designing a garment can be influenced by the sensory experience created by different ragas in Indian classical music which had an influence on color, texture, silhouette, and embellishment of the garment. -

Machine Learning Approaches for Mood Identification in Raga: Survey

International Journal of Innovations in Engineering and Technology (IJIET) Machine Learning Approaches for Mood Identification in Raga: Survey Priyanka Lokhande Department of Computer Engineering Maharashtra Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India Bhavana S. Tiple Department of Computer Engineering Maharashtra Institute of Technology, Pune, Maharashtra, India Abstract- Music is a “language of emotion”, which defines the emotion or feeling through music. Music directly connects to the soul and induces emotion in mind and brains. In Hindustani Classical Music raga plays very important role. It defines characteristics that differentiate ragas uniquely. Hindustani Classical Music also has nine different swaras that specifically define the emotion. In this paper we surveyed different techniques for raga identification and differentiate them according to their work and accuracy. We give the rasa - bhava relationship and raga-rasa mapping that defines the emotion related to raga. Keywords – Indian Classical Music, Emotion, Raga- Rasa relation, Classifiers. I. INTRODUCTION Indian classical music: One of an ancient tradition is Indian classical music that is an art form that is continuously growing. It has its roots in Sam Veda. Indian classical music is divided into two branches: Carnatic (South Indian Classical Music) and Hindustani (North Indian Classical Music). Carnatic music is sharp and involves many rhythmic and tonal complexities. Hindustani is mellifluous and meant to be entertainment and pleasure oriented music. Indian classical music and Western music vary from each other with respect to their notes, timings and different characteristics associated with raga. Swaras of Indian classical music are similar to the note of western classical music. There are many characteristics of Hindustani classical music. -

A Comparative Study of Carnatic and Hindustani Raga Systems by Neural Network Approach

International Journal of Neural Networks ISSN: 2249-2763 & E-ISSN: 2249-2771, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2012, pp.-35-38. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000238 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CARNATIC AND HINDUSTANI RAGA SYSTEMS BY NEURAL NETWORK APPROACH SRIMANI P.K.1 AND PARIMALA Y.G.2* 1Department of Computer Science and Maths, Bangalore-560 056, Karnataka, India. 2City Engineering College, VTU, Bangalore-560 062, Karnataka, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: October 25, 2012; Accepted: November 06, 2012 Abstract- A unique Neural network approach has been used in the present investigations and a comparative study of the raga systems of Carnatic (CCM) and Hindustani classical music (HCM). The paper concerns a detailed study of the melakartha-janya raga system of CCM, Thaat-raaga system of HCM and cognitive studies of the same based on Artificial Neural networks (ANN). For CCM, studies were confined to the 72 melakartha ragas. For HCM 101 ragas were considered. Relative frequencies of notes in the scales were used as inputs. 100% accuracy was obtained for the melakartha system of CCM for several network topologies while highest accuracy was about 80% in case of HCM. Several networks, namely MLP, PCA, GFF, LR, RBF, TLRN were analyzed and consolidate report was generated. Keywords- Carnatic classical music, Hindustani classical music, thaats, melakartha ragas, cognition. Citation: Srimani P.K. and Parimala Y.G. (2012) A Comparative Study of Carnatic and Hindustani Raga Systems by Neural Network Ap- proach. International Journal of Neural Networks, ISSN: 2249-2763 & E-ISSN: 2249-2771, Volume 2, Issue 1, pp.-35-38.