Legislative Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

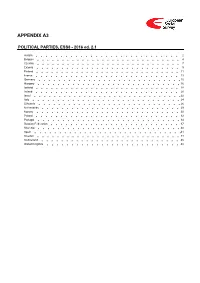

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Rise and Fall of the Icelandic Constitutional Reform Movement: the Interaction Between Social Movements and Party Politics

157 The Rise and Fall of the Icelandic Constitutional Reform Movement: The Interaction Between Social Movements and Party Politics SHIOTA Jun * Abstract This article traces the rise and fall of the Icelandic constitutional reform movement, which emerged following the financial crisis of 2008. The movement grew out of the popular protest that arose in face of the crisis. We draw on the political process approach to examine how the movement declined despite some remarkable initial progress, such as the championing of a participatory drafting process. We find that the movement had serious challenges in terms of social control, collective attribution, movement network, and political opportunities. The movement faced tough setbacks partly derived from the traditional rural-capital dynamics in Icelandic politics. Moreover, the linkage with institutional actors was weak although ratification by parliament is necessary for the implementation of a new constitution. The populistic movement frame motivated the participants in the beginning, however this was later impeded by the anti-foreign debt protests. The 2013 election was the final straw because the left-wing government, which supported the movement, was replaced by a right-wing government which was hostile to the new constitution. In conclusion, the paper finds that recognizing the dynamic interrelation between social movements and institutional politics is important if we are to understand today’s social changes. Keywords:Iceland, Constitutional reform movement, Political process approach, Party politics, Financial crisis * Ph.D student in Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies, Kobe University. Journal of International Cooperation Studies, Vol.27, No.1(2019.7) P157-塩田.indd 157 2019/07/04 18:38:25 158 国 際 協 力 論 集 第 27 巻 第 1 号 Introduction The financial crisis which unfolded in 2008 and the following austerity politics triggered massive social mobilization in many European countries. -

Analyzing Icelandic Support for EU Membership

It’s ot the Economy, Stupid? Analyzing Icelandic Support for EU Membership K. Amber Curtis Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder UCB 333 Boulder, CO 80309-0333 [email protected] Joseph Jupille Department of Political Science University of Colorado at Boulder UCB 333 Boulder, CO 80309-0333 ABSTRACT: What drives support for EU membership? We test the determinants of EU attitudes using original data from Iceland, whose recent woes have received wide attention. Given its crisis, we expect economic anxiety to drive public opinion. We find instead that economic unease is entirely mediated by assessments of the current government and that, despite the dire economic context, cultural concerns predominate. This suggests a potential disconnect between Icelandic elites’ desire for accession and the public will at large. Our results largely confirm prior findings on support for integration, further exposing the conditions under which individuals will evaluate EU membership favorably or negatively. They also highlight the utility of mediation analysis for identifying the mechanisms through which economic evaluations may operate and imply that economic indicators’ apparent insignificance in a host of other research areas may simply be a product of model misspecification. Paper prepared for presentation at the Annual Meeting of the European Union Studies Association, Boston, MA, Mar. 3-5, 2011. Jupille gratefully acknowledges financial support from National Science Foundation (NSF) Award #SES-1035102 (“RAPID: A Referendum on Debt: The Political Economy of Icesave”). What drives public support for European Union (EU) membership? Though this question would seem exhausted by decades of scholarship, we are particularly interested in two less commonly explored conditions: 1) public opinion in new candidate countries—as opposed to existing member states—and 2) individual attitudes in the context of economic duress. -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

The 2008 Icelandic Bank Collapse: Foreign Factors

The 2008 Icelandic Bank Collapse: Foreign Factors A Report for the Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs Centre for Political and Economic Research at the Social Science Research Institute University of Iceland Reykjavik 19 September 2018 1 Summary 1. An international financial crisis started in August 2007, greatly intensifying in 2008. 2. In early 2008, European central banks apparently reached a quiet consensus that the Icelandic banking sector was too big, that it threatened financial stability with its aggressive deposit collection and that it should not be rescued. An additional reason the Bank of England rejected a currency swap deal with the CBI was that it did not want a financial centre in Iceland. 3. While the US had protected and assisted Iceland in the Cold War, now she was no longer considered strategically important. In September, the US Fed refused a dollar swap deal to the CBI similar to what it had made with the three Scandinavian central banks. 4. Despite repeated warnings from the CBI, little was done to prepare for the possible failure of the banks, both because many hoped for the best and because public opinion in Iceland was strongly in favour of the banks and of businessmen controlling them. 5. Hedge funds were active in betting against the krona and the banks and probably also in spreading rumours about Iceland’s vulnerability. In late September 2008, when Glitnir Bank was in trouble, the government decided to inject capital into it. But Glitnir’s major shareholder, a media magnate, started a campaign against this trust-building measure, and a bank run started. -

The Iceland Experiment (2009-2013): a Participatory Approach to Constitutional Reform

The Iceland Experiment (2009-2013): A Participatory Approach to Constitutional Reform DPC Policy Note New Series # 02 B by Hannah Fillmore-Patrick C Sarajevo, August 2013 www.democratizationpolicy.org A report from Democratization Policy Council (DPC) guest author: Hannah Fillmore-Patrick * Editing: DPC Editorial Board Layout: Mirela Misković Sarajevo, August 2013 * Hannah Fillmore-Patrick has a B.A. in English Literature from Colby College in Waterville, Maine, USA, and is currently pursuing a M.L.A. in International Law at the American University in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Originally tackling issues of governance and authority in literary classics like Gulliver's Travels and The Tempest, she is now interested in the way modern civil societies improve their governments in times of crisis through grassroots campaigns like Iceland's thjodfundurs. [email protected] www.democratizationpolicy.org TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... I INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 ROOTS OF THE REVISION .............................................................................................................................. 1 The Financial Collapse ......................................................................................................... 1 The Kitchenware Revolution .............................................................................................. -

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Major Political Parties Coverage for Data Collection 2021 Country Major

Major political parties Coverage for data collection 2021 Country Major political parties EU Member States Christian Democratic and Flemish (Chrétiens-démocrates et flamands/Christen-Democratisch Belgium en Vlaams/Christlich-Demokratisch und Flämisch) Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste/Socialistische Partij/Sozialistische Partei) Forward (Vooruit) Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten) Reformist Movement (Mouvement Réformateur) New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie) Ecolo Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) Workers' Party of Belgium (Partij van de Arbeid van België) Green Party (Groen) Bulgaria Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (Grazhdani za evropeysko razvitie na Balgariya) Bulgarian Socialist Party (Bulgarska sotsialisticheska partiya) Movement for Rights and Freedoms (Dvizhenie za prava i svobodi) There is such people (Ima takav narod) Yes Bulgaria ! (Da Bulgaria!) Czech Republic Mayors and Independents STAN (Starostové a nezávislí) Czech Social Democratic Party (Ceská strana sociálne demokratická) ANO 2011 Okamura, SPD) Denmark Liberal Party (Venstre) Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne/Socialdemokratiet) Danish People's Party (Dansk Folkeparti) Unity List-Red Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) Danish Social Liberal Party (Radikale Venstre) Socialist People's Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti) Conservative People's Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) Germany Christian-Democratic Union of Germany (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands) Christian Social Union in Bavaria (Christlich-Soziale -

Redalyc.Icelandic and Spanish Citizens Before the Crisis: Size

Revista de Economía Mundial ISSN: 1576-0162 [email protected] Sociedad de Economía Mundial España Cabiedes Miragaya, Laura Icelandic And Spanish Citizens Before The Crisis: Size Matters... And Institutions Too Revista de Economía Mundial, núm. 43, 2016, pp. 205-234 Sociedad de Economía Mundial Madrid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=86647324010 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative ICELANDIC AND SPANISH CITIZENS BEFORE THE CRISIS: SIZE MATTERS… AND INSTITUTIONSISSN: 1576-0162TOO 205 ICELANDIC AND SPANISH CITIZENS BEFORE THE CRISIS: SIZE MATTERS… AND INSTITUTIONS TOO LOS CIUDADANOS ESPAÑOLES E ISLANDESES ANTE LA CRISIS: EL TAMAÑO IMPORTA… Y LAS INSTITUCIONES TAMBIÉN Laura Cabiedes Miragaya Universidad de Oviedo [email protected] Accésit del VIII Premio Jose Luís Sampedro ABSTRACT In this paper, a comparative analysis between the main political citizen at- titudes before the crisis in Iceland and Spain is carried out. After a brief review of political and economical antecendents, it was concluded that in Spain, as well as in Iceland, the key explanatory factors of the deep economic imbal- ances are located at the institutional sphere. The excesses are related in both cases to political clientelism and to diverse corruptions practices, in such a way that even the alarming signs that preceded “the official date” of the eco- nomic crisis, no convenient measures were adopted in time. In this context, the crisis has played a catalyst role, accelerating the demands aimed at achieving a better performance of the democratic system in both countries. -

Pirate Parties: the Social Movements of Electronic Democracy

JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS 49 PIRATE PARTIES: THE SOCIAL MOVEMENTS OF ELECTRONIC DEMOCRACY Dmytro KHUTKYY1 ………………………………………………………………………….………………………………… Contemporary technologies facilitate democratic participation in a digital form. And Pirate Parties claim to represent such an empowered electronic democracy. Thereby this study examines whether Pirate Parties are actually social movements practicing and promoting electronic democracy. For this aim, the research applies the ‘real utopias’ framework exploring desirable, viable, and achievable alternative social designs. In terms of methods, the inquiry is based on the analysis of expert interviews and political manifestos. The study revealed that Pirate Parties are genuine democratic initiatives, widely implementing principles and mechanisms of electronic democracy. Overall, the studied Pirate Parties foster member participation at all stages of policy making. Even though Pirate Parties have achieved low electoral results for public offices, their models of internal democratic organization and political ideas are proliferated by other parties. Key words: democracy; e-democracy; participatory democracy; political parties; social movements. 1 INTRODUCTION The modern digitization of public life presumes that democracy can be realized also by online participation in politics. Such electronic democracy can be defined as “the use of information and communication technologies and strategies by democratic actors (governments, elected officials, the media, political organizations, citizen/voters) within political and governance processes of local communities, nations and on the international stage” (Clift 2004). Moreover, Earl and Kimport (2011) argued that Internet allows easier and more cost-effective means for online communication, mobilization for offline protests, e-activism via e-participation instruments, and self-organizing for e-movements. Besides, given the global character of Internet, e-participation can transcend boundaries and evolve at large scale – at regional, national, and even supranational levels. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 5056 Category 2: Public Choice November 2014

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Gylfason, Thorvaldur Working Paper Constitution on Ice CESifo Working Paper, No. 5056 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Gylfason, Thorvaldur (2014) : Constitution on Ice, CESifo Working Paper, No. 5056, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/105112 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Constitution on Ice Thorvaldur Gylfason CESIFO WORKING PAPER NO. 5056 CATEGORY 2: PUBLIC CHOICE NOVEMBER 2014 An electronic version of the paper may be downloaded • from the SSRN website: www.SSRN.com • from the RePEc website: www.RePEc.org • from the CESifo website: www.CESifoT -group.org/wp T CESifo Working Paper No. -

Icelandic Law

Volume 56 Issue 1 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 56, 1951-1952 10-1-1951 Icelandic Law Lester B. Orfield Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation Lester B. Orfield, Icelandic Law, 56 DICK. L. REV. 42 (1951). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol56/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DICKINSON LAW REVIEW VOL. 56 ICELANDIC LAW By LESTER B. ORFIELD* Because of its connection with Norway from its first settlement in 874 up to 1814 and because of its connection with Denmark from 1380 to 1944 Iceland is of peculiar interest to all Scandinavians.' As Arnold J. Toynbee has so beautifully phrased it, "the finest flowering of an oversea Scandinavian polity was the republic of Iceland, founded on the apparently unpromising soil of an Arctic island, five hundred miles away from the nearest Scandinavian point d'appui in the Faroe Islands."2 The same author states that "it was in Iceland, and not in Norway, Sweden or Denmark, that the abortive Scandinavian Civilization achieved its greatest triumphs in literature and in politics.'' 3 Iceland is of no less interest to the United States. Many Icelanders have settled in the United States during the past century. Our troops were stationed in Ice- land during World War II and even a half a year before the United States entered the war.