Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE of BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320)

1 [The following essay was published in the Jewish Studies Quarterly 5 (1998) 318-28. The essay appears here substantially as published but with some additions indicated in this color .]. RABBINIC KNOWLEDGE OF BLACK AFRICA (Sifre Deut. 320) David M. Goldenberg While the biblical corpus contains references to the people and practices of black Africa (e.g. Isa 18:1-2), little such information is found in the rabbinic corpus. To a degree this may be due to the different genre of literature represented by the rabbinic texts. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that black Africa and its peoples would be entirely unknown to the Palestinian Rabbis of the early centuries. An indication of such knowledge is, I believe, found imbedded in a midrashic text of the third century. Deut 32:21 describes the punishment God has decided to inflict on Israel for her disloyalty to him: “I will incense them with a no-folk ( be-lo < >am ); I will vex them with a nation of fools ( be-goy nabal ).” A tannaitic commentary to the verse states: ואני אקניאם בלא עם : אל תהי קורא בלא עם אלא בלוי עם אלו הבאים מתוך האומות ומלכיות ומוציאים אותם מתוך בתיהם דבר אחר אלו הבאים מברבריא וממרטניא ומהלכים ערומים בשוק “And I will incense them with a be-lo < >am .” Do not read bl < >m, but blwy >m, this refers to those who come from among the nations and kingdoms and expel them [the Jews] from their homes. Another interpretation: This refers to those who come from barbaria and mr ãny <, who go about naked in the market place. -

Grids and Datumsâšrepublic of Sudan

REPUBLIC OF rchaeological excavation of sites on the Nile above Aswan has confirmed human “Ahabitation in the river valley during the Paleolithic period that spanned more than 60,000 years of Sudanese history. By the eighth millennium B.C., people of a Neolithic culture had settled into a sedentary way of life there in fortified mud-brick villages, where they supplemented hunting and fishing on the Nile with grain gathering and cattle herding. Contact with Egypt probably occurred at a formative stage in the culture’s development because of the steady movement of population along the Nile River. Skeletal remains suggest a blending of negroid and Mediterranean populations during the Neolithic period (eighth to third millenia B.C.) that has remained relatively stable until theDelivered present, by Ingenta despite gradual infiltrationIP: 192.168.39.211by other elements. On: Sat, 25 Sep 2021 12:42:54 Copyright: American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing Northern Sudan’s earliest historical record comes from Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream from the first cataract, called Cush, as “wretched.” For more than 2,000 years after the Old kingdom emerged at Karmah, near present-day Dunqulah. After Egyptian power revived during the New Kingdom (ca. Kingdom (ca. 2700-2180 B.C.), Egyptian political 1570-1100 B.C.), the pharaoh Ahmose I incorporated Cush and economic activities determined the course as an Egyptian province governed by a viceroy. Although of the central Nile region’s history. Even during Egypt’s administrative control of Cush extended only down to intermediate periods when Egyptian political power the fourth cataract, Egyptian sources list tributary districts in Cush waned, Egypt exerted a profound cultural reaching to the Red Sea and upstream to the confluence of the and religious influence on the Cushite people. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Late Antiquity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8tq0h18g Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Ruffini, Giovanni Publication Date 2018-04-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LATE ANTIQUITY اﻟﻌﺼﺮ اﻟﻘﺪﯾﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺎﺧﺮ Giovanni Ruffini EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford WOLFRAM GRAJETZKI Area Editor Time and History University College London JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Ruffini, 2018, Late Antiquity. UEE. Full Citation: Ruffini, Giovanni, 2018, Late Antiquity. In Wolfram Grajetzki and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002kd2bn 15615 Version 1, April 2018 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002kd2bn LATE ANTIQUITY اﻟﻌﺼﺮ اﻟﻘﺪﯾﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺎﺧﺮ Giovanni Ruffini Spätantike Antiquité tardive Late antique Egypt ran from the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian (284-305 CE) to the Arab conquest of Egypt (641 CE). During this period, Egypt was part of the eastern Roman Empire and was ruled from Constantinople from the founding of that city in the 320s CE. Culturally, Egypt’s elite were part of the wider Roman world, sharing in its classical education. However, several developments marked Egypt’s distinctiveness in this period. These developments included the flourishing of literature in Coptic, the final written form of the native language, and the creation and rapid growth of several forms of monastic Christianity. These developments accompanied the expansion of Christianity throughout the countryside and a parallel decline in the public role of native religious practices. -

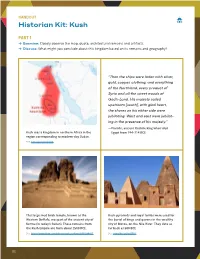

Historian Kit: Kush

HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush PART 1 → Examine: Closely observe the map, quote, architectural remains and artifacts. → Discuss: What might you conclude about this kingdom based on its remains and geography? “Then the ships were laden with silver, gold, copper, clothing, and everything of the Northland, every product of Syria and all the sweet woods of God’s-Land. His majesty sailed upstream [south], with glad heart, the shores on his either side were jubilating. West and east were jubilat- ing in the presence of his majesty.” — Piankhi, ancient Kushite king who ruled Kush was a kingdom in northern Africa in the Egypt from 744–714 BCE region corresponding to modern-day Sudan. See: http://bit.ly/2KbAl8G This large mud brick temple, known as the Kush pyramids and royal tombs were used for Western Deffufa, was part of the ancient city of the burial of kings and queens in the wealthy Kerma (in today’s Sudan). These remains from city of Meroe, on the Nile River. They date as the Kush Empire are from about 2500 BCE. far back as 500 BCE. See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/waltercallens/3486244425 See: http://bit.ly/3qhZDBl 22 HANDOUT Historian Kit: Kush (continued) This stone carving (1st century BCE) is from the temple of Amun in the ancient city of Naqa. It depicts a kandake (female leader) This piece of gold jewelry was found in the from Meroe. Named Amanishakheto, she tomb of Nubian King Amaninatakilebte stands between a god and goddess. (538–519 BC). See: http://bit.ly/3oGqWFi See: https://www.flickr.com/photos/menesje/47758289472 IMAGE SOURCES Lommes and National Geographic. -

Egyptian Traditional Temples in the Graeco-Roman Period

• جامعة املنيا- لكية الس ياحة والفنادق • قسم ا إلرشاد الس يايح- الفرقة الثالثة • مقرر: آ اثر مرص القدمية 5 )اجلزء اليوانين والروماين( • عنوان احملارضة: معبد الكبشة • آس تاذ املادة: د/ يرسي النشار •الربيد الالكرتوين لﻻس تفسارات: [email protected] The Temple of Kalabsha Location The ancient Egyptian temple of Kalabsha is the largest free-standing temple of Lower Egyptian Nubia located about 50 km south of Aswan and built of sandstone masonry. Date of construction While the temple was constructed in Augustus’s reign, it was never finished. The temple dates back to the Roman Emperor Augustus, 30 BC, but the colony of Talmis evidently dates back to at least the reign of Amenhotep II in 1427 - 1400 BC. Deity It was originally constructed over an earlier sanctuary of Amenhotep II. The temple was dedicated to the Nubian fertility and solar deity known as Mandulis. Mandulis was originally a Nubia deity also worshipped in Egypt. The name Mandulis is the Greek form of Merul or Melul, a non-Egyptian name. The centre of his cult was the temple of Kalabsha at Talmis. The worship of Mandulis was unknown in Egypt under the native Pharaohs. Architecture The design of the temple is classical for the Ptolemaic period, with pylon, courtyard, hypostyle hall and a three-room sanctuary. On the edge of the river is a cult terrace or quay, from which a paved causeway leads to the 34 m broad pylon, which is slightly at an angle to the axis of the temple. The pylon gateway gives entrance to an open court, which is surrounded by colonnades along three of its sides. -

Imperial Legitimacy in the Roman Empire of the Third Century: AD

Imperial Legitimacy in the Roman Empire of the Third Century: AD 193 – 337 by Matthew Kraig Shaw, B.Com., B.A. (Hons), M.Teach. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts University of Tasmania, July 2010 This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Matthew Shaw iii This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. This thesis does not contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: Matthew Shaw iv Abstract. Septimius Severus, according to Cassius Dio, told his sons to enrich the soldiers and look down on all other men (Cass. Dio 77.15.2). This recognised the perceived importance of the army in establishing and maintaining the legitimacy of an emperor. This thesis explores the role of the army in the legitimation of emperors. It also considers whether there were other groups, such as the Senate and people, which emperors needed to consider in order to establish and maintain their position as well as the methods they used to do so. Enriching the soldiers was not the only method used and not the only way an emperor could be successful. The rapid turn over of emperors after Septimius' death, however, suggests that legitimacy was proving difficult to maintain even though all emperors all tried to establish and maintain the legitimacy of their regime. -

Egypt Under Roman Rule: the Legacy of Ancient Egypt I ROBERT K

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY OF EGYPT VOLUME I Islamic Egypt, 640- I 5 I 7 EDITED BY CARL F. PETRY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE CONTENTS The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 IRP, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, CB2 2Ru, United Kingdom http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY roorr-42rr, USA http://www.cup.org ro Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3 r66, Australia © Cambridge University Press r998 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published r998 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge List of illustrations to chapter I 3 ix List of contributors x Typeset in Sabon 9.5/r2 pt [CE] Preface xm A cataloguerecord for this book is available from the British Library Note on transliteration xv Maps xvi ISBN o 5 2r 4 7r 3 7 o hardback r Egypt under Roman rule: the legacy of Ancient Egypt I ROBERT K. RITNER 2 Egypt on the eve of the Muslim conquest 34 WALTER E. KAEGI 3 Egypt as a province in the Islamic caliphate, 641-868 62 HUGH KENNEDY 4 Autonomous Egypt from Ibn Tuliin to Kafiir, 868-969 86 THIERRY BIANQUIS 5 The Isma'ili Da'wa and the Fatimid caliphate I20 PAUL E. WALKER 6 The Fatimid state, 969-rr7r IJ I PAULA A. -

The Empire Strikes: the Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C

The Empire Strikes: The Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C. – A.D. 68 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by David Schwei M.A., University of Cincinnati, December 2012 B.A., Emory University, May 2009 Committee Chairs: Peter van Minnen, Ph.D Barbara Burrell, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Coins permeated the Roman Empire, and they offer a unique perspective into the ability of the Roman state to implement its decisions in Italy and the provinces. This dissertation examines how this ability changed and grew over time, between 60 B.C. and A.D. 68, as seen through coin production. Earlier scholars assumed that the mint at Rome always produced coinage for the entire empire, or they have focused on a sudden change under Augustus. Recent advances in catalogs, documentation of coin hoards, and metallurgical analyses allow a fuller picture to be painted. This dissertation integrates the previously overlooked coinages of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt with the denarius of the Latin West. In order to measure the development of the Roman state’s infrastructural power, this dissertation combines the anthropological ideal types of hegemonic and territorial empires with the numismatic method of detecting coordinated activity at multiple mints. The Roman state exercised its power over various regions to different extents, and it used its power differently over time. During the Republic, the Roman state had low infrastructural minting capacity. -

Imperium Romanum - Scenarios © 2018 Decision Games

Imperium© 2018 DecisionRomanum Games - Scenarios 1 BX-U_ImperiumRom3-Scenarios_V4F.indd 1 10/10/18 10:38 AM # of Players No. Name Dates Period Max/Min/Opt. Page Number 1 The Gallic Revolt * Nov. 53 to Oct. 52 BC 1 2 4 2 Pompey vs. the Pirates * (1) Apr. to Oct. 67 BC 1 2 5 3 Marius vs. Sulla July 88 to Jan. 82 BC 1 4/3/3 6 4 The Great Mithridatic War June 75 to Oct. 72 BC 1 3 8 5 Crisis of the First Triumvirate Feb. 55 to Sep. 52 BC 1 6/4/5 10 6 Caesar vs. Pompey Nov. 50 to Aug. 48 BC 2 2 12 7 Caesar vs. the Sons of Pompey July 47 to May 45 BC 2 2 13 8 The Triumvirs vs. the Assassins Dec. 43 to Dec. 42 BC 2 2 15 9 Crisis of the Second Triumvirate Jan. 38 to Sep. 35 BC 2 5/3/4 16 10 Octavian vs. Antony & Cleopatra Apr. 32 to Aug. 30 BC 2 2 18 11 The Revolt of Herod Agrippa (1) AD March 45-?? 3 2 19 12 The Year of the Four Emperors AD Jan. 69 to Dec. 69 3 4/3/3 20 13 Trajan’s Conquest of Dacia * (1) AD Jan. 101 to Nov. 102 3 2 22 14 Trajan’s Parthian War (1) AD Jan. 115 to Aug. 117 3 2 23 15 Avidius Cassius vs. Pompeianus (1) AD June 175-?? 3 2 25 16 Septimius Severus vs. Pescennius Niger vs. AD Apr. 193 to Feb. -

Ancient Egypt in Africa

i ENCOUNTERS WITH ANCIENT EGYPT Bodjfou$Fhzqu jo$Bgsjdb Institute of Archaeology ii Ancient Egypt in Africa Ujumft$jo$uif$tfsjft Ancient Egypt in Africa Edited by David O’Connor and Andrew Reid Ancient Perspectives on Egypt Edited by Roger Matthews and Cornelia Roemer Consuming Ancient Egypt Edited by Sally MacDonald and Michael Rice Imhotep Today: Egyptianizing architecture Edited by Jean-Marcel Humbert and Clifford Price Mysterious Lands Edited by David O’Connor and Stephen Quirke ‘Never had the like occurred’: Egypt’s view of its past Edited by John Tait Views of Ancient Egypt since Napoleon Bonaparte: imperialism, colonialism and modern appropriations Edited by David Jeffreys The Wisdom of Egypt: changing visions through the ages Edited by Peter Ucko and Timothy Champion iii ENCOUNTERS WITH ANCIENT EGYPT Bodjfou$Fhzqu jo$Bgsjdb Edited by David O’Connor and Andrew Reid Institute of Archaeology iv Ancient Egypt in Africa First published in Great Britain 2003 by UCL Press, an imprint of Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom Telephone: + 44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: + 44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: www.uclpress.com Published in the United States by Cavendish Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services, 5824 NE Hassalo Street, Portland, Oregon 97213-3644, USA Published in Australia by Cavendish Publishing (Australia) Pty Ltd 45 Beach Street, Coogee, NSW 2034, Australia Telephone: + 61 (2)9664 0909 Facsimile: + 61 (2)9664 5420 © Institute of Archaeology, University College London 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of Cavendish Publishing Limited, or as expressly permitted by law, or under the terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. -

Lecture Transcript: the Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe By

Lecture Transcript: The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe by Solange Ashby Sunday, August 30, 2020 Louise Bertini: Hello, everyone, and good afternoon or good evening, depending on where you are joining us from, and thank you for joining our August member-only lecture with Dr. Solange Ashby titled "The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe." I'm Dr. Louise Bertini, and I'm the Executive Director of the American Research Center in Egypt. First, some brief updates from ARCE: Our next podcast episode will be released on September 4th, featuring Dr. Nozomu Kawai of Kanazawa University titled "Tutankhamun's Court." This episode will discuss the political situation during the reign of King Tutankhamun and highlight influential officials in his court. It will also discuss the building program during his reign and the possible motives behind it. As for upcoming events, our next public lecture will be on September 13th and is titled "The Karaites in Egypt: The Preservation of Egyptian Jewish Heritage." This lecture will feature a panel of speakers including Jonathan Cohen, Ambassador of the United States of America to the Arab Republic of Egypt, Magda Haroun, head of the Egyptian Jewish Community, Dr. Yoram Meital, professor of Middle East Studies at Ben-Gurion University, as well as myself, representing ARCE, to discuss the efforts in the preservation of the historic Bassatine Cemetery in Cairo. Our next member-only lecture will be on September 20th with Dr. Jose Galan of the Spanish National Research Council in Madrid titled "A Middle Kingdom Funerary Garden in Thebes." You can find out more about our member-only and public lectures series schedule on our website, arce.org.