I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04

Tea - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 03-11-09 12:04 Tea From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tea is the agricultural product of the leaves, leaf buds, and internodes of the Camellia sinensis plant, prepared and cured by various methods. "Tea" also refers to the aromatic beverage prepared from the cured leaves by combination with hot or boiling water,[1] and is the common name for the Camellia sinensis plant itself. After water, tea is the most widely-consumed beverage in the world.[2] It has a cooling, slightly bitter, astringent flavour which many enjoy.[3] The four types of tea most commonly found on the market are black tea, oolong tea, green tea and white tea,[4] all of which can be made from the same bushes, processed differently, and in the case of fine white tea grown differently. Pu-erh tea, a post-fermented tea, is also often classified as amongst the most popular types of tea.[5] Green Tea leaves in a Chinese The term "herbal tea" usually refers to an infusion or tisane of gaiwan. leaves, flowers, fruit, herbs or other plant material that contains no Camellia sinensis.[6] The term "red tea" either refers to an infusion made from the South African rooibos plant, also containing no Camellia sinensis, or, in Chinese, Korean, Japanese and other East Asian languages, refers to black tea. Contents 1 Traditional Chinese Tea Cultivation and Technologies 2 Processing and classification A tea bush. 3 Blending and additives 4 Content 5 Origin and history 5.1 Origin myths 5.2 China 5.3 Japan 5.4 Korea 5.5 Taiwan 5.6 Thailand 5.7 Vietnam 5.8 Tea spreads to the world 5.9 United Kingdom Plantation workers picking tea in 5.10 United States of America Tanzania. -

Teahouses and the Tea Art: a Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie Master's Thesis in East Asian Culture and History (EAST4591 – 60 Credits – Autumn 2015) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 24 November, 2015 © LI Jie 2015 Teahouses and the Tea Art: A Study on the Current Trend of Tea Culture in China and the Changes in Tea Drinking Tradition LI Jie http://www.duo.uio.no Print: University Print Center, University of Oslo II Summary The subject of this thesis is tradition and the current trend of tea culture in China. In order to answer the following three questions “ whether the current tea culture phenomena can be called “tradition” or not; what are the changes in tea cultural tradition and what are the new features of the current trend of tea culture; what are the endogenous and exogenous factors which influenced the change in the tea drinking tradition”, I did literature research from ancient tea classics and historical documents to summarize the development history of Chinese tea culture, and used two month to do fieldwork on teahouses in Xi’an so that I could have a clear understanding on the current trend of tea culture. It is found that the current tea culture is inherited from tradition and changed with social development. Tea drinking traditions have become more and more popular with diverse forms. -

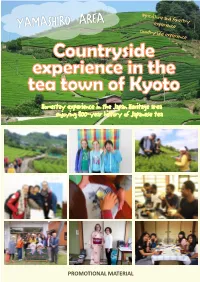

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT Contentsissue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark

GL BAL EA HUT Tea & Tao Magazine 國際茶亭 December 2018 紅 印 藍 印印 級 Masterpiece Era Puerh GLOBAL EA HUT ContentsIssue 83 / December 2018 Tea & Tao Magazine Blue藍印 Mark To conclude this amazing year, we will be explor- ing the Masterpiece Era of puerh tea, from 1949 to 1972. Like all history, understanding the eras Love is of puerh provides context for today’s puerh pro- duction. These are the cakes producers hope to changing the world create. And we are, in fact, going to drink a com- memorative cake as we learn! bowl by bowl Features特稿文章 37 A Brief History of Puerh Tea Yang Kai (楊凱) 03 43 Masterpiece Era: Red Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 53 Masterpiece Era: Blue Mark Chen Zhitong (陳智同) 37 31 Traditions傳統文章 03 Tea of the Month “Blue Mark,” 2000 Sheng Puerh, Yunnan, China 31 Gongfu Teapot Getting Started in Gongfu Tea By Shen Su (聖素) 53 61 TeaWayfarer Gordon Arkenberg, USA © 2018 by Global Tea Hut 藍 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be re- produced, stored in a retrieval system 印 or transmitted in any form or by any means: electronic, mechanical, pho- tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the copyright owner. n December,From the weather is much cooler in Taiwan.the We This is an excitingeditor issue for me. I have always wanted to are drinking Five Element blends, shou puerh and aged find a way to take us on a tour of the eras of puerh. Puerh sheng. Occasionally, we spice things up with an aged from before 1949 is known as the “Antique Era (號級茶時 oolong or a Cliff Tea. -

A Required Taste

Tea Classics A Required Taste Tea Culture Among 16th Century Literary Circles as Seen Through the Paintings of Wen Zhengming 一 個 茶人: Michelle Huang 必 修 Some of the authors we are translating in this issue are very 品 well known to Chinese scholars and laymen alike. And even 味 if these specific authors weren’t known to a Chinese reader, 文 they at least would have studied enough Chinese history to contextualize these works in the Ming Dynasty: its culture, 徵 art and politics. Also, we only got to read parts of Wen’s 明 “Superfluous Things,” those having to do with tea, so this -ar 的 ticle on his life and times by our local Chinese art historian, Michelle, who has contributed to many past issues of Global 畫 Tea Hut, can help us all to construct a bit of Ming China in our imaginations and thereby enrich our reading of the texts. en Zhengming 文徵明 tivity for literary figures since the dawn most other gentlemen to work on his W (1470–1559) was a of civilization, the booming economy art and tea-related research. He wrote a famous artist in the late and the increasing availability of pub- systematic commentary on an existing Ming Dynasty in Suzhou, which was lic transportation since the 15th centu- work, the Record of Tea by Cai Xiang a hot spot for literary figures. He came ry in China made it easier for people (1012–1067),3 which was titled Com- from a family of generations of officials to travel longer distances. -

Adapting to Climate Change: Challenges for Uji Tea Cultivation

International Journal Sustainable Future for Human Security FORESTRY AGRICULTURE J-SustaiN Vol.3, No.1 (2015) 32-36 http://www.j-sustain.com Adapting to Climate 1. Uji Tea Cultivation Although Uji Tea might not be a familiar name Japanese Change: Challenges for Uji green tea is very much popular as a high quality tea with Tea Cultivation health benefit properties among tea enthusiast. Even so what is commonly known about Japanese green tea would Fitrio Ashardionoa*, Monte Cassimb be matcha or sen-cha which are types of green tea, whereas information about the location of the tea growing region is a Ritsumeikan University, 2-150 Iwakura-cho, Ibaraki, Osaka not known. Uji Area is the oldest and most famous tea 567-8570, Japan growing region in Japan in which according to historical b Ritsumeikan Research Center for Sustainability Science, 56-1 archive tea cultivation in the area begins in 1191 AD [1]. Toji-in Kitamachi Kita-ku, Kyoto 603-8577, Japan Originally Uji Tea refers to tea products which are Received: January 27, 2015/ Accepted: April 24, 2015 cultivated within the borders of Uji Area, and it is well known for its extraordinary quality as it only caters to the Abstract nobility. Because of its resource consuming methods, traditionally the tea produced in Uji Area is only available in Rapid changes in the climatic conditions have becoming a low volume, therefore in order to comply with the more evident with increasing degree of its intensity and continuous high demand from consumers, the Kyoto Tea extremities. Direct effects of these changes are felt by Cooperative (京都府茶業組合) (2006) [2] defined Uji Tea as agriculture industries especially those which are utilizing tea products which are grown in four prefectures: Kyoto, terroir elements, environmental of a certain area and its Nara, Shiga and Mie; but processed inside Kyoto Prefecture human interaction such as the tea cultivation industry in Uji Area. -

Stamp Collection Event

STAMP COLLECTION EVENT park of the ① Collect 4 stamps or more ② Answer a simple questionnaire at booth S-1/S-2 ③ Participate in a lottery wheel to win prizes! lawn n the ot o refo ba alk W - 1 2・1 3・1 4 w ! ! W-3 t’s d friends Tokyo Le ily an Collect 4 stamps Eat F-2 Washoku Communicate Fukushima Feel Feel W-20 Shinjuku city r fam Broadcasting you or more to get prize Instant Photo Studio ith System Television, Inc w for participation ① ② ③ ④ Project: Connecting and Supporting Forests, Countryside, Rivers, and Sea Buy Enjoy Prize for participation Take a photo Do coloring Sat. Sun. “ Washoku” menu “Shinjuku no Mori” 10:00 -16:00 「Fudegaki」(fruit) 10/5 6 GTF REIWA 1,000 person a day Grand Green Tea Ceremony first-come Hosted By GTF Greater Tokyo Festival Committee first-served basis. Co-Hosted By Ministry of the Environment Nature Conservation Bureau / Ministry of the Environment Fukushima Regional Environmental Office / Japan Committee for UNDB / Shinjuku City / TOKYO FM / Tokyo Broadcasting System Television, Inc. / ⑤ ⑥ Tokyo Metropolitan Television Broadcasting Corp. W - 2 3・2 4 W-22 All Nippon Airways Ice Breaker SHIRASE Join Quiz Quiz Feel Stage Co., Ltd. Stage MC:Marie Takahashi Time Schedule 1 3 12 20 1 3 12 20 1 3 12 13 20 1 8 19 20 Collect 12 small stamps (Sat.) (Sun.) List of 10:30 5 10:30 6 performers to receive a special stamp 1 Opening Ceremony 11 Opening Ceremony , ⑦ ⑧ Hosts, Co-hosts, Makoto, DANCE KID S (Jazz Dance) at booth S-1 Maya Hayashi, Saki Nakajima, 10:45 BEYOOOOONS, BlueEarthProject 10:40 12 Opening Makoto Saki Nakajima -

Amagase Dam in Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture Attractiveness Boosting Project

MLIT Japan Infrastructure Tourism Attractiveness Boosting Project Transform the public infrastructures into new tourism resources Initiatives for Infrastructure Tourism in Japan In addition to Amagase Dam, the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport, and Tourism is making a progressive approach toward developing more attractive internal tours of infrastructure facilities and construction sites throughout Japan. For more information, please visit the Infrastructure Tourism Portal Website…Search by “infrastructure tourism” ■ Metropolitan Area Outer ■ Yanba Dam Gunma Underground Discharge Channel Saitama Amagase Suspension Bridge Amagase Dam in Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture (Under construction view) ©Byodoin Yanba Dam is the latest dam that started operation in April, 2020. Amphibious Three types of courses are available to see the interior of the gigantic buses, sightseeing boats, canoes, and SUP will be in service in the future. “Disaster Prevention Underground Temple.” (Contact) (Contact) Attractiveness Naganohara Town Hall: 0279-82-2244 Tour Reception at Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel: 048-747-0281 Boosting Project Ujikami Shrine ■ Akashi Kaikyo Bridge Hyogo ■ Yunishigawa Dam Amphibian Bus Tochigi m m is is ur ur to to e e ur ur ct ct ru ru st st fra fra in in by by for Touris to to tion m i o o da n J y y en ap K K m an m in in o c e K m m y R s s o i i r r t w u u o e o o t t T N w w o e e u n n r f f The Tale of Genji Museum i o o s ion ion m t t Photo by Honshu-Shikoku Bridge Expressway Company Limited za za f ali ali o it it r ev ev R R F u Experience a 360º panorama view of the world’s longest suspension bridge The open-air bus dives directly into the dam lake for sightseeing. -

It Was During the Kamakura Period That the Custom of Drinking Tea in Japan Was Popularized by Eisai, a Japanese Buddhist Monk

It was during the Kamakura period that the custom of drinking tea in Japan was popularized by Eisai, a Japanese Buddhist monk. Ever since then tea has been an integral part of Japanese culture and daily life, from traditional tea ceremonies to the millions of cups of sencha that are now consumed each day. There are lots of different types of tea and many different regions in Japan that grow it, however it is the region of Uji which is regarded by many to produce the best quality tea in the country, as well as having a very significant role in the history of Japanese tea. Earlier this year I was fortunate enough to be invited to a tea farm in Uji to learn more about the process of growing tea and the history of Ujicha (Uji tea). Uji itself is just south of Kyoto, just under 30 minutes by train on the Nara line. At Uji JR station I met up with the rest of my group, a Japanese English teacher and some Japanese students, we then jumped on a bus heading out into the countryside. About 10 miles later the bus dropped us at the side of the road, we were then picked up by a few cars that the owners of the tea farm had kindly driven out to bring us further up the narrow winding roads to the tea farm. We arrived at a small group of houses which was the base of the tea farm, after some introductions with the owner and employees we where then taken up a very steep winding track that led up the hill through the tall trees behind the houses. -

Tea-Picking Women in Imperial China

Beyond the Paradigm: Tea-Picking Women in Imperial China Lu, Weijing. Journal of Women's History, Volume 15, Number 4, Winter 2004, pp. 19-46 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/jowh.2004.0015 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jowh/summary/v015/15.4lu.html Access provided by Scarsdale High School (3 Apr 2013 11:11 GMT) 2004 WEIJING LU 19 BEYOND THE PARADIGM Tea-picking Women in Imperial China Weijing Lu This article explores the tension between women’s labor and tea-pick- ing through the Confucian norm of “womanly work.” Using local gaz- etteer and poetry as major sources, it examines the economic roles and the lives of women tea-pickers over the course of China’s imperial his- tory. It argues that women’s work in imperial China took on different meanings as ecological settings, economic resources, and social class shifted. The very commodity—tea—that these women produced also shaped portrayals of their labor, turning them into romantic objects and targets of gossip. But women tea-pickers also appeared as good women with moral dignity, suggesting the fundamental importance of industry and diligence as female virtues in imperial China. n imperial China, “men plow and women weave” (nangeng nüzhi) stood I as a canonical gender division of labor. Under this model, a man’s work place was in the fields: he cultivated the land and tended the crops, grow- ing food; a woman labored at home, where she sat at her spindle and loom, making cloth. -

The Manufacturing and Drinking Arts in the Song Dynasty. the Manufacturing and Drinking Arts in the Song Dynasty

The manufacturing and drinking arts in the Song dynasty. Shen Dongmei The Institute of History, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences 5 Jiannei Road, Beijin 100732, P.R. of China Summary Crumby-cake tea was the main form of tea production in the Song period, and it was steamed green tea. It had mainly six working procedures: plucking, picking, steaming, grinding, compressing, and baking. The various particular standards in each procedure formed the character of tea in the Song period, which was obviously different from tea in the Tang period. Corresponding to the shape of dust tea, the leading style of tea drinking in the Song period was called pointing tea, which had five steps, such as compressed tea grinding, sieving tea, optimizing the tea brewing, warming cup by fife, and pointing tea. Each of the five steps requires special utensils. It is only all the steps did its best can the tea infusion be fme. Fencha (tea game) and Doucha (tea competition) was the artistic, emulative form of pointing tea, all of which correlated to the leisurely and elegant lives of literati in Song China. In the course of tea culture history, pointing tea, the drinking art of the Song period, formed a connecting link between boiling tea of the Tang period and brewing tea of the Ming and Qing periods. Pointing tea 'was spread to Japan and other countries and areas from China in the Song period, making its particular contribution to the tea culture of the world. Keywords dust tea, manufacturing, drinking arts, the Song dynasty Under the joint affection of the change of tea manufacturing style and social spiritual value orientation, compared with the Tang dynasty, the tea art of the Song dynasty had made fairly development on some procedure of tea manufacturing, style of tea shape, art of pointing tea, tea utensils, the standard of appreciation etc., far more delicate than the later, which made the Song dynasty the special historic period with distinct style in Chinese tea culture history. -

Tea History the People’S Drink

Sources : http://english.teamuseum.cn/ViewContent8_en.aspx?contentId=372 http://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/chinese-tea/ http://www.china.org.cn/learning_chinese/Chinese_tea/2011-07/15/content_22999489.htm http://www.teavivre.com/info/the-history-of-chinese-tea-in-general/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_tea_in_China https://www.yoyochinese.com/blog/learn-mandarin-chinese-tea-culture-why-is-tea-so-popular-in-china http://www.china-travel-tour-guide.com/about-china/chinese-tea.shtml http://www.sacu.org/tea.html http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/matt-taibbi-on-the-tea-party-20100928 http://www.bl.uk/reshelp/findhelpregion/asia/china/guidesources/chinatrade/ http://www.dilmahtea.com/ceylon-tea/history-of-ceylon-tea http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/585115/tea https://tregothnan.co.uk/about/tea-plantation/a-brief-history-of-tea/ http://www.teavana.com/tea-info/history-of-tea http://wissotzky.ru/about-tea_history.aspx http://www.travelchinaguide.com/intro/cuisine_drink/tea/ http://www.twinings.co.uk/about-twinings/history-of-twinings https://qmhistoryoftea.wordpress.com http://inventors.about.com/od/tstartinventions/ss/tea.htm https://www.bigelowtea.com/Special-Pages/Customer-Service/FAQs/General,-Tea-Related/What-is-the-history-of-tea http://www.revolutiontea.com/history-of-tea.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tea_in_the_United_Kingdom http://www.huffingtonpost.com/lisa-mirza-grotts/the-history-and-etiquette_b_3751053.html http://britishfood.about.com/od/AfternoonTea/ss/Afternoon-Tea-Recipes.htm http://teainengland.com