Hege Dypedokk Johnsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jones, David Albert, the Soul of the Embryo

J The Soul of the Embryo: An enquiry into the status of the human embryo in the Christian tradition DAVID ALBERT JONES • , continuum A LONDON • NEW YORK Continuum The Tower Building 15 East 26th Street 11 York Road New York London, SE1 7NX NY 10010 www.continuumbooks.com C) David Jones 2004 Contents All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Abbreviations A catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. Foreword ISBN 0 8264 6296 0 Introduction 1 Moulded in the Earth The embryo in the Hebrew Scriptures: creation, Typeset by BookEns Ltd, Royston, Herts. providence, calling Printed and hound in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts. 2 Curdled Like Cheese Ancient embryology: Hippocrates and Aristotle 3 Discarded Children • Exposure, infanticide and abortion in ancient Greece and Rome 4 Grieving in Ramah Jewish attitudes to infanticide and abortion 5 Medicinal Penalties Early Christianity and abortion: Celtic/Anglo-Saxon penances, Greek/Latin canons 6 Soul Talk Soul as the principle of life, body and soul, the I would like to thank Fr Michael Hayes, Head of the School of Theology, spiritual soul Philosophy and History at St Mary's College for supporting an ethos of research 7 Whence the Soul? and scholarship within the School; Robin Baird-Smith of Continuum books for The Church Fathers on the origin of the soul: his great patience; and the Linacre Centre for Healthcare Ethics for the use of pre-existence, traducianism, creationism their excellent library. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Arsenokoités and Malakos: Meanings and Consequences by Dale B

Arsenokoités and Malakos: Meanings and Consequences by Dale B. Martin The New Testament provides little ammunition to those wishing to condemn modern homosexuality. Compared to the much more certain condemnations of anger, wealth (sometimes anything but poverty), adultery, or disobedience of wives and children, the few passages that might be taken as condemning homosexuality are meager. It is not surprising, therefore, that the interpretation of two mere words has commanded a disproportionate amount of attention. Both words, arsenokoités and malakos, occur in a vice list in 1 Cor. 6:9, and arsenokoités recurs in 1 Tim. 1:10. Although the translation of these two words has varied through the years, in the twentieth century they have often been taken to refer to people who engage in homosexual, or at least male homosexual, sex, and the conclusion sometimes then follows that the New Testament or Paul, condemns homosexual "activity." Usually the statement is accompanied by a shrugged-shoulder expression, as if to say, I'm not condemning homosexuality! I'm just reading the Bible. It's there in the text. Such protestations of objectivity, however, become untenable when examined closely. By analyzing ancient meanings of the terms, on the one hand, and historical changes in the translation of the terms on the other, we discover that interpretations of arsenokoités and malakos as condemning modern homosexuality have been driven more by ideological interests in marginalizing gay and lesbian people than by the general strictures of historical criticism. In the end, the goal of this chapter is not mere historical or philological accuracy. -

Performing Masculinities in the Greek Novel

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses Playing the man: Performing masculinities in the Greek novel. Jones, Meriel How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Meriel (2007) Playing the man: Performing masculinities in the Greek novel.. thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa42521 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ Playing the Man: Performing Masculinities in the Greek Novel Meriel Jones Submitted to the University o f Wales in fulfilment o f the requirements for the degree o f Doctor ofPhilosophy. Swansea University 2007 ProQuest Number: 10805270 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Bible, the Church, & Homosexuality

FAMILY RESEARCH COUNCIL lthough the leading Christian churches in the United States continue to view homosexual behavior as outside the realm of appropriate Christian conduct, revisionist scholars within their respective communions cont- inue a campaign to re-interpret or ignore biblical teaching regarding homosexuality. Exposing the faulty reasoning behind the gay hermeneutic, The Bible, The Church, and Homosexuality demonstrates how homosexuality is unambiguously found wanting by Scripture and tradition. TIMOTHY J. DAILEY is Senior Fellow in the Center for Marriage and Family Studies at the Family Research Council. His study is based upon his doctoral dissertation, completed at Marquette University. The , ChurchtheBible & Homosexuality EXPOSING THE ‘GAY’ THEOLOGY family research council tony perkins, president 801 g street nw BL04F01 washington, dc 20001 TIMOTHY J. DAILEY www.frc.org The , ChurchtheBible & Homosexuality EXPOSING THE ‘GAY’ THEOLOGY The Bible, the Church, and Homosexuality: Exposing the ‘Gay’ Theology by Timothy J. Dailey © 2004 by the Family Research Council All rights reserved. Scripture passages identified asNRSV are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture passages identified asNIV are taken from the Holy Bible: New International Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. The “NIV” and “New International Version” trademarks are registered in the United States Patent and Trademark Office by the International Bible Society. Family Research Council 801 G Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20001 Printed in the United States of America. -

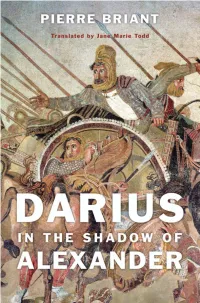

Darius in the Shadow of Alexander

Darius in the Shadow of Alexander DARIUS IN THE SHADOW OF ALEXANDER PIERRE BRIANT TRANSLATED BY JANE MARIE TODD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, EN GLAND 2015 Copyright © 2015 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First printing Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the French Ministry of Foreign Aff airs and the Cultural Ser vices of the French Embassy in the United States. First published as Darius dans l’ombre d’Alexandre by Pierre Briant World copyright © Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2003. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Briant, Pierre. [Darius dans l’ombre d’Alexandre. En glish] Darius in the shadow of Alexander / Pierre Briant ; translated by Jane Marie Todd. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 49309- 4 (alkaline paper) 1. Darius III, King of Persia— 330 B.C. 2. Iran— Kings and rulers— Biography. 3. Iran— History—To 640. 4. Alexander, the Great, 356 B.C.– 323 B.C. I. Title. DS284.7.B7513 2015 935'.705092—dc23 [B] 2014018170 Contents Ac know ledg ments vii Preface to the English- Language Edition ix Translator’s Note xvii Introduction: Between Remembering and Forgetting 1 I THE IMPOSSIBLE BIOGRAPHY 1. A Shadow among His Own 15 2. Darius Past and Present 65 II CONTRASTING PORTRAITS 3. “The Last Darius, the One Who Was Defeated by Alexander” 109 4. Arrian’s Darius 130 5. A Diff erent Darius or the Same One? 155 6. Darius between Greece and Rome 202 vi Contents III RELUCTANCE AND ENTHUSIASM 7. -

![[Individuality and Love in Plato]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5676/individuality-and-love-in-plato-4945676.webp)

[Individuality and Love in Plato]

Love and the Individual The Morality of Platonic Love and its Metaphysical Presuppositions by Hege Dypedokk Johnsen Thesis presented for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Supervised by Professor Øyvind Rabbås Department of Philosophy, Classics, History of Art and Ideas Faculty of Humanities UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2011 II Suppose you were molding gold into every shape there is, going on non-stop remolding one shape into the next. If someone then were to point at one of them and ask you, “What is it?”, your safest answer by far, with respect to the truth, would be to say “gold”, but never “triangle” or any of the other shapes that come to be in the gold, as though it is these, because they change even while you‟re making the statement. Timeaus, 50a–b “That,” he said, “is my speech about Love, Eryximachus. It is rather different from yours. As I begged you earlier, don‟t make comedy of it…” Symposium, 193d III IV Abstract What is it that we really love when we love an individual person, and to what extent are we egoistical in the search for happy love? Moreover, what/whom should we love, and for what reason? I approach the subject “Love and the Individual” by analyzing Gregory Vlastos‟ two main charges against Plato‟s theory of love: Firstly, that Plato‟s theory fails to give a satisfying account of love directed from one individual towards another individual; and secondly, that it is essentially egoistical. Throughout the thesis I underscore the points considered vulnerable to criticism, and highlight the phenomena subjected to insufficient treatment. -

And Theology Biblical Theology Bulletin: a Journal of Bible

Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology http://btb.sagepub.com No Kingdom of God for Softies? or, What Was Paul Really Saying? 1 Corinthians 6:9 10 in Context John H. Elliott Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology 2004; 34; 17 DOI: 10.1177/014610790403400103 The online version of this article can be found at: http://btb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/34/1/17 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Biblical Theology Bulletin Inc. Additional services and information for Biblical Theology Bulletin: A Journal of Bible and Theology can be found at: Email Alerts: http://btb.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://btb.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://btb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/34/1/17 Downloaded from http://btb.sagepub.com at AUGUSTANA COLLEGE LIBRARY on April 1, 2010 No Kingdom of God for Softies? or, What Was Paul Really Saying? 1 Corinthians 6:9-10 in Context John H. Ellioft Abstract The search for biblical texts on “homosexuals” and “homosexual ac!ivity” presents a particularly prickly problem of contextual reading and interpretation. It involves, among other things, a clash of ancient and modern sexual concepts, constructs, and frames of reference. Attempts at using allegedly relevant texts as moral guidelines today are subject to serious exegetical and hermeneutical constraints. ong the issues currently challenging the US. church ual” and “homosexual” “orientation,” and operative moral across the denominations, there is none producing as much heat guidelines. -

Greece: Ancient by Eugene Rice

Greece: Ancient by Eugene Rice Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The institution of pederasty (paiderastia) was a conspicuous feature of ancient Greek public and private life. The gods had boyfriends. Poseidon desired Pelops, seduced him, and took him to Olympus in a golden chariot. Radiant Apollo loved Hyacinthus, the youngest and handsomest son of a king of Sparta, and taught him archery, music, divination, and all the exercises of the wrestling ring. According to the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite: Wise Zeus abducted fair-haired Ganymede For his beauty, to be among the immortals And pour wine for the gods in the house of Zeus, A marvel to look upon, honoured by all the gods. The earliest documented instances of man-boy relationships date from the second half of the seventh century B.C.E. For nearly a millennium, texts and artifacts of varying Top: A bust of Sappho. quantity, interest, and weight confirm the ubiquity of pederasty in the Greek-speaking Center: A ceramic object world. Herodotus, the first great historian in the Western tradition, included depicting a scene of "copulating with boys" in a list of the "good things of life." pederastic seduction (ca 480 B.C.E.). The Structure of Early Greek Pederasty Above: A bust of Socrates. Photograph by Eric Gaba. The model of pederasty current in archaic and classical Greece paired a citizen of the polis (the Greek city-state), by definition a freeborn adult male, and a boy of equal origin, class, and status. -

YARBROUGH-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf (1.181Mb)

Copyright by Colin Warner Yarbrough 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Colin Warner Yarbrough Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Xenophon on Athens: Between Democracy and Oligarchy Committee: Paula Perlman, Supervisor Cristina Carusi Thomas Palaima Stephen White Paul Woodruff Xenophon on Athens: Between Democracy and Oligarchy by Colin Warner Yarbrough Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2018 Dedication For Bailee Acknowledgements It seems that this dissertation has presented me with one last difficulty, but at least I can say that this difficulty is a joyful one: trying to remember all those who deserve my thanks and gratitude for helping me bring it to completion. No project of this magnitude or emotional energy can be completed alone, and I have many, many people to thank. I want to start by offering thanks to my dissertation committee: Paula Perlman, Cristina Carusi, Thomas Palaima, Stephen White, and Paul Woodruff. Thank you for all your support along the way and for the time and careful attention that you dedicated to the final product. I want to offer a special thank you to my supervisor, Paula Perlman, for all that she has done to see this project through, sticking with me through what at times seemed a lost project, especially in these last few months as everything has come rather rapidly together. Your wisdom and instruction have shaped me into the scholar that I am today. -

The Passions of the Good Citizen Aldo Mosca

The passions of the good citizen Aldo Mosca The passions are forms in matter. Aristotle, De Anima. The passions are those things through which, by undergoing change, people come to differ in their judgments, and which are accompanied by distress and pleasure. Aristotle, On Rhetoric. Temper seems to pay some attention to reason, but to hear it imperfectly -- just as eager servants go darting off before hearing the end of what is said to them. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics. 1. If Plato was an idealist visionary, Aristotle was the philosopher of reality and commonsense. He developed a theory of the soul as a set of faculties of human beings made out of matter against Plato's conception of it as an immaterial substance trapped in the body, and argued for the good life of the sensible citizen against the ascetic ideal of the philosopher-ruler. He did not reject the ethical prescription of the control of the passions by the rational will, but saw them -- as long as they were kept within reasonable limits -- as acceptable and positive aspects of a fully realized individual, the active member of the political community. Aristotle is indeed one of the few philosophers who were friends of the passions. His celebrated view of man as a "political animal" was somewhat outdated, to be sure, and even a little hypocritical, when he advanced it. It was then around 340 b.c.e. and Aristotle, after studying at Plato's Academy for twenty years, and after a few more years of independent research especially in biology, had been summoned to the court of Philip, king of the Macedons, to supervise the education of his son, Alexander. -

Edhina Ekogidho – Names As Links the Encounter Between African and European Anthroponymic Systems Among the Ambo People in Namibia

minna saarelma-maunumaa Edhina Ekogidho – Names as Links The Encounter between African and European Anthroponymic Systems among the Ambo People in Namibia Studia Fennica Linguistica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Anna-Leena Siikala Rauno Endén Teppo Korhonen Pentti Leino Auli Viikari Kristiina Näyhö Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Minna Saarelma-Maunumaa Edhina Ekogidho – Names as Links The Encounter between African and European Anthroponymic Systems among the Ambo People in Namibia Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki Studia Fennica Linguistica 11 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2003 Minna Saarelma-Maunumaa and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2003 by the Finnish Literature Society. Cover Design: Timo Numminen EPUB Conversion: Tero Salmén ISBN 978-951-746-529-8 (Print) ISBN 978-952-222-816-1 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-222-820-8 (EPUB) ISSN 0085-6835 (Studia Fennica) ISSN 1235-1938 (Studia Fennica Linguistica) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.21435/sflin.11 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.