Taoa/Best Advocacy Project Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNITED REPUBLIC of TANZANIA Tanzania Airports Authority

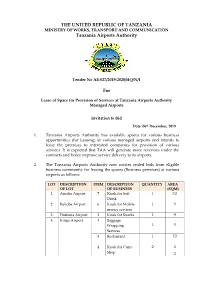

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA MINISTRY OF WORKS, TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATION Tanzania Airports Authority Tender No AE-027/2019-2020/HQ/N/1 For Lease of Space for Provision of Services at Tanzania Airports Authority Managed Airports Invitation to Bid Date: 06th December, 2019 1. Tanzania Airports Authority has available spaces for various business opportunities (for Leasing) at various managed airports and intends to lease the premises to interested companies for provision of various services. It is expected that TAA will generate more revenues under the contracts and hence improve service delivery to its airports. 2. The Tanzania Airports Authority now invites sealed bids from eligible business community for leasing the spaces (Business premises) at various airports as follows: LOT DESCRIPTION ITEM DESCRIPTION QUANTITY AREA OF LOT OF BUSINESS (SQM) 1. Arusha Airport 7 Kiosk for Soft 1 33 Drink 2. Bukoba Airport 6 Kiosk for Mobile 1 4 money services 3. Dodoma Airport 3 Kiosk for Snacks 1 4 4. Iringa Airport 1 Baggage Wrapping 1 4 Services 3 Restaurant 1 72 4 Kiosk for Curio 2 3 Shop 3 LOT DESCRIPTION ITEM DESCRIPTION QUANTITY AREA OF LOT OF BUSINESS (SQM) 5 Kiosk for Retail 1 3.5 shop 5. Kigoma Airport 1 Baggage Wrapping 1 4 Services 2 Restaurant 1 19.49 3 Kiosk for Retail 2 19.21 shop 4 Kiosk for Snacks 1 9 5 Kiosk for Curio 1 6.8 Shop 6. Kilwa Masoko 1 Restaurant 1 40 Airport 2 Kiosk for soft 1 9 drinks 7. Lake Manyara 2 Kiosk for Curio 10 84.179 Airport Shop 3 Kiosk for Soft 1 9 Drink 4 Kiosk for Ice 1 9 Cream and Beverage Outlet 5 Car Wash 1 49 6 Kiosk for Mobile 1 2 money services 8. -

ITINERARY for ROMANTIC EAST AFRICA SAFARI Tanzania & Zanzibar

ITINERARY FOR ROMANTIC EAST AFRICA SAFARI Tanzania & Zanzibar Let your imagination soar Journey overview Indulge in the drama of East Africa’s most beautiful landscapes, from the romance of classical safari to the wonder of breath-taking landscapes and the barefoot luxury of a private island. At Lake Manyara you will share a cosy tree house in the heart of a scenic landscape, where lions lounge in the forks of trees and pink flamingo wade near the lakeshore. Enjoy a taste of adventure combined with the ultimate luxury on the open plains of the Serengeti, where Persian carpets and fully sized beds are separated from the African night by only a thin sheet of canvas and the light of lanterns sparkles on silver and crystal as your private feast is served in the open air. Wrap yourself in the glamour and decadence of another era as you gaze out at endless misty views of the Ngorongoro Crater from beside a blazing fireplace. End your adventure with a moonlight walk on the white beaches of andBeyond Mnemba Island, serenaded by the whisper of the waves. HIGHLIGHTS OF THE ITINERARY: � Exceptional game viewing in the renowned Serengeti National Park � Viewing the abundance of birds in Lake Manyara National Park and the curious antics of tree-climbing lions � Explore Lake Manyara by bicycle � Peering over the edge of the world’s largest intact caldera in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area � Tucking into truly mouth-watering seafood feasts � Friendly encounters with soul-tickling personalities MAKE THE MOST OF YOUR ADVENTURE: � Glide high above the Serengeti on a Hot-air balloon safari � Walk in the first footsteps of our ancestors in the Cradle of Mankind at Olduvai Gorge � Dance in a Masaai Village and make new friends � No stay on Zanzibar is complete without spending a day or night in Stone Town. -

Register of IJS Locations V1.Xlsx

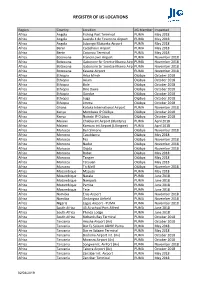

REGISTER OF IJS LOCATIONS Region Country Location JIG Member Inspected Africa Angola Fishing Port Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Luanda 4 de Fevereiro Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Angola Lubango Mukanka Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cadjehoun Airport PUMA May 2018 Africa Benin Cotonou Terminal PUMA May 2018 Africa Botswana Francistown Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Gaborone Sir Seretse Khama AirpoPUMA November 2018 Africa Botswana Kasane Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Ethiopia Arba Minch OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Axum OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Bole OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Dire Dawa OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Gondar OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jijiga OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ethiopia Jimma OiLibya October 2018 Africa Ghana Kotoka International Airport PUMA November 2018 Africa Kenya Mombasa IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Kenya Nairobi IP OiLibya OiLibya October 2018 Africa Malawi Chileka Int Airport (Blantyre) PUMA April 2018 Africa Malawi Kamuzu int.Airport (Lilongwe) PUMA April 2018 Africa Morocco Ben Slimane OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Casablanca OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Fez OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Nador OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Oujda OiLibya November 2018 Africa Morocco Rabat OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tangier OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tetouan OiLibya May 2018 Africa Morocco Tit Melil OiLibya November 2018 Africa Mozambique Maputo -

Download Factsheet

INCENTIVES & EVENTS FOR CORPORATE RETREATS AND RECEPTIONS Recognise and reward your team for their dedication to the job with a one-of-a-kind encounter. Blessed by bountiful natural treasures and steeped in a melting pot of civilisations, The Residence Zanzibar offers numerous leisure and sightseeing activities to strengthen bonds and foster relationships. These shared experiences, together with the days spent relaxing by the private pool, savouring the unique blend of cuisines, and enjoying the sensational spa treatments will linger in the mind of every guest, translating into year-long involvement and motivation. LEISURE & TEAM BUILDING ACTIVITIES With plenty to see and do in and around the resort, there's hardly a dull moment. Adventure and relaxation seekers alike can revel in the range of options that are within easy reach, while spouse programmes keep everyone blissfully pampered. Daytrips can also be organised to explore attractions surrounding the vicinity. ON-SITE FACILITIES Even after the meetings are over, there's plenty to do at The Residence Zanzibar. Conveniently situated within the resort confines are a spa developed with renowned British brand ila, as well as a host of recreational activities to suit all tastes. › Spa & Fitness › Bicycles › Cooking classes › Water Sports › Yoga › Dive Centre › Tennis › Volleyball OFF-SITE ACTIVITIES Should you need a breather from all that conferencing, venture out to discover the treasures that Zanzibar has to offer. Take your pick from a wide range of options with our tour partners, subject -

The United Republic of Tanzania Judiciary

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA JUDICIARY IN THE HIGH COURT OF TANZANIA (DISTRICT REGISTRY OF MBEYA) AT MBEYA MISC. LAND APPLICATION NO. 19 OF 2019 (From the District Land and Housing Tribunal for Kyela at Kyela in Land Appeal No. 03 of 2018. Originating from Katumbasongwe Ward Tribunal in Land Case No. 15 of 2017) STADE M W ASEBA.......................................................................................... APPLICANT VERSUS EDWARD MWAKATUNDU......................................................................... RESPONDENT RULING Date of Hearing: 27/11/2019 Date of Ruling : 14/02/2020 MONGELLA, J. The Applicant is seeking before this Court for extension of time within which to lodge his appeal out of time against the decision of the District Land and Housing Tribunal for Kyela in Land Appeal No. 03 of 2018. The application is brought under section 38(1) of the Land Disputes Courts Act, 2002. He is represented by Mr. Osward Talamba, learned counsel. In the affidavit sworn by the Applicant in support of his application as well in the submissions made by his Advocate, Mr. Talamba, the Applicant advanced two main reasons for seeking the extension of time. The. first Page 1 of 8 reason is that the Applicant fell sick and was receiving treatment in various hospitals between 24th June 2018 and 7th March 2019, something which prevented him from filing the appeal within time. To support his claim he presented medical documents. Mr. Talamba also cited the case of Richard Mgala & 9 Others v. Aikael Minja & 4 Others, Civil Application No. 160 of 2015 and argued that in this case sickness was accepted as a good reason to warrant extension of time. -

Global Volatility Steadies the Climb

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Global volatility steadies the climb Cirium Fleet Forecast’s latest outlook sees heady growth settling down to trend levels, with economic slowdown, rising oil prices and production rate challenges as factors Narrowbodies including A321neo will dominate deliveries over 2019-2038 Airbus DAN THISDELL & CHRIS SEYMOUR LONDON commercial jets and turboprops across most spiking above $100/barrel in mid-2014, the sectors has come down from a run of heady Brent Crude benchmark declined rapidly to a nybody who has been watching growth years, slowdown in this context should January 2016 low in the mid-$30s; the subse- the news for the past year cannot be read as a return to longer-term averages. In quent upturn peaked in the $80s a year ago. have missed some recurring head- other words, in commercial aviation, slow- Following a long dip during the second half Alines. In no particular order: US- down is still a long way from downturn. of 2018, oil has this year recovered to the China trade war, potential US-Iran hot war, And, Cirium observes, “a slowdown in high-$60s prevailing in July. US-Mexico trade tension, US-Europe trade growth rates should not be a surprise”. Eco- tension, interest rates rising, Chinese growth nomic indicators are showing “consistent de- RECESSION WORRIES stumbling, Europe facing populist backlash, cline” in all major regions, and the World What comes next is anybody’s guess, but it is longest economic recovery in history, US- Trade Organization’s global trade outlook is at worth noting that the sharp drop in prices that Canada commerce friction, bond and equity its weakest since 2010. -

The United Republic of Tanzania

TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY PUBLIC NOTICE THE TANZANIA CIVIL AVIATION (LICENSING OF AIR SERVICES) REGULATIONS, 2006 AND (GROUND HANDLING SERVICES) REGULATIONS, 2012 BOARD DECISIONS ON APPLICATIONS FOR AIR AND GROUND HANDLING SERVICES LICENCES At its 30th Ordinary Board Meeting held through a video conference on 10 June 2020, Tanzania Civil Aviation Authority’s Board of Directors considered, among other things, applications for air and ground handling services licences from companies/operators listed hereunder and reached the following decisions: A. APPLICANTS FOR AIR SERVICES LICENCES S/No. APPLICANT TYPE OF APPLICATION SERVICE (S) APPLIED FOR BOARD DECISION 1. M/S Warnercom (T) New application Scheduled air service for Approved for a period of Limited cargo on the following routes: one (1) year for domestic P. O. Box 78482 routes. International routes 1 S/No. APPLICANT TYPE OF APPLICATION SERVICE (S) APPLIED FOR BOARD DECISION Dar es salaam, Tanzania. a) Dar-Kilimanjaro-Dar; will be considered by the b) Dar-Mwanza-Dar; Authority on case-by-case c) Dar-Songwe-Dar; based on Bilateral Air d) Dar es Salaam-Doha Services Agreements (Qatar)-Dar es salaam; between Tanzania and e) Dar es Salaam-Sharjah respective countries upon (UAE)-Dar es salaam; f) Dar es Salaam-Hahaya requests. (Comoro) -Dar es Salaam; g) Dar es Salaam-Jeddah- Medina-Dar es Salaam; h) Dar es Salaam-Netherlands- Dar es Salaam; i) Dar es Salaam-Mumbai-Dar es Salaam; j) Dar es Salaam-Nairobi- Uganda-Dar es Salaam; k) Dar es Salaam- Johannesburg-Dar es Salaam; l) Dar es Salaam-Kigali-DRC- Dar es Salaam. -

World Bank Document

Zanzibar: A Pathway to Tourism for All Public Disclosure Authorized Integrated Strategic Action Plan July 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 List of Abbreviations CoL Commission of Labour DMA Department of Museums and Antiquities (Zanzibar) DNA Department of National Archives (Zanzibar) GDP gross domestic product GoZ government of Zanzibar IFC International Finance Corporation ILO International Labour Organization M&E monitoring and evaluation MoANRLF Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources, Livestock and Fisheries (Zanzibar) MoCICT Ministry of Construction, Industries, Communication and Transport (Zanzibar) MoEVT Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (Zanzibar) MoFP Ministry of Finance and Planning (Zanzibar) MoH Ministry of Health (Zanzibar) MoICTS Ministry of Information, Culture, Tourism and Sports (Zanzibar) MoLWEE Ministry of Lands, Water, Energy and Environment (Zanzibar) MoTIM Ministry of Trade, Industry and Marketing (Zanzibar) MRALGSD Ministry of State, Regional Administration, Local Government and Special Departments (Zanzibar) NACTE National Council for Technical Education (Tanzania) NGO nongovernmental organization PPP private-public partnership STCDA Stone Town Conservation and Development Authority SWM solid waste management TISAP tourism integrated strategic action plan TVET technical and vocational education and training UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation UWAMWIMA Zanzibar Vegetable Producers’ Association VTA Vocational -

Dodoma Aprili, 2019

JAMHURI YA MUUNGANO WA TANZANIA WIZARA YA UJENZI, UCHUKUZI NA MAWASILIANO HOTUBA YA WAZIRI WA UJENZI, UCHUKUZI NA MAWASILIANO MHESHIMIWA MHANDISI ISACK ALOYCE KAMWELWE (MB), AKIWASILISHA BUNGENI MPANGO NA MAKADIRIO YA MAPATO NA MATUMIZI YA FEDHA KWA MWAKA WA FEDHA 2019/2020 DODOMA APRILI, 2019 HOTUBA YA WAZIRI WA UJENZI, UCHUKUZI NA MAWASILIANO MHESHIMIWA MHANDISI ISACK ALOYCE KAMWELWE (MB), AKIWASILISHA BUNGENI MPANGO NA MAKADIRIO YA MAPATO NA MATUMIZI YA FEDHA KWA MWAKA WA FEDHA 2019/2020 A. UTANGULIZI 1. Mheshimiwa Spika, baada ya Mwenyekiti wa Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Miundombinu kuweka mezani Taarifa ya Utekelezaji wa Mpango na Bajeti ya Wizara, naomba sasa kutoa hoja kwamba Bunge lako Tukufu likubali kupokea na kujadili Taarifa ya Utekelezaji wa Mpango na Bajeti ya Wizara ya Ujenzi, Uchukuzi na Mawasiliano kwa mwaka wa fedha 2018/2019. Aidha, naomba Bunge lako Tukufu lijadili na kupitisha Mpango na Bajeti ya Wizara kwa mwaka wa fedha 2019/2020. 2. Mheshimiwa Spika, nianze kwa kumshukuru Mwenyezi Mungu kwa kutujalia uhai na kutuwezesha kukutana tena leo kujadili maendeleo ya shughuli zinazosimamiwa na sekta za Ujenzi, Uchukuzi na Mawasiliano. 3. Mheshimiwa Spika, nitumie fursa 1 hii kuwapongeza Mheshimiwa Dkt. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli, Rais wa Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania, Mheshimiwa Dkt. Alli Mohammed Shein, Rais wa Serikali ya Mapinduzi ya Zanzibar, Mheshimiwa Samia Suluhu Hassan, Makamu wa Rais wa Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania na Mheshimiwa Kassim Majaliwa Majaliwa (Mb.), Waziri Mkuu wa Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania kwa uongozi wao thabiti ambao umewezesha kutekelezwa kwa mafanikio makubwa Ilani ya Uchaguzi ya CCM ya mwaka 2015, ahadi za Viongozi pamoja na kutatua kero mbalimbali za wananchi. -

Arusha Airport Reviews

Arusha Airport Reviews Arusha Airport (IATA: ARK, ICAO: HTAR) is a small airport serving Arusha, Tanzania. The airport is currently undergoing an expansion which includes an extension of the current runway and new terminal buildings. The airport served 87,252 passengers in 2004. Arusha Airport’s operator is Tanzania Airports Authority (TAA) was founded in 1999 by an Act of Parliament. The Authority is responsible for the provision of airport services; airport management services; ground support; business planning; airport expansion within Tanzania; construction of airports and airport facilities; and whatever else in entailed in the sustenance of the aviation industry in Tanzania. The Authority operates under the purview of the Ministry of Infrastructure Development. Arusha airport airlines are Coastal Aviation, Precision Air, Regional Air, Tropical Air, and ZanAir. While destinations are the following Dar es Salaam, Kilimanjaro, Mafia Island, Manyara, Mikumi, Mwanza, Pemba Island, Ruaha, Selous, Serengeti, Seronera, Tanga, Tarangire, Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, Kilimanjaro, Manyara, Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam, Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam, Mombasa, Pemba Island, Zanzibar. Services: ATMs / Cash Machines – info not available Car Rentals – info not available Children’s Play Areas – info not available Currency Exchange – info not available Food / Restaurants – Yes (restaurants, bars and coffee shops) Information Desk – info not available Luggage Storage / Lockers – info not available Downloaded from www.airtport.reviews Showers – info not available Internet: info not available Airport opening hours: Open 24 hours Website: Arusha Airport Official Website Arusha Airport Map Arusha Airport Weather Forecast [yr url=”http://www.yr.no/place/Tanzania/Arusha/Arusha_Airport/” links=”0″ table=”1″ ] Downloaded from www.airtport.reviews. -

Ndutu Safari Lodge Fact Sheet

NDUTU SAFARI LODGE FACT SHEET Ndutu Safari Lodge is situated in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area in the southern Serengeti ecosystem. The Lodge nestles unobtrusively under a canopy of giant acacias looking towards a soda lake, Lake Ndutu. The Lodge offers a superb base in which to explore the range of habitats that lie within easy reach, this include swamps, woodlands, soda lakes and the world famous Serengeti short grass plains. Ndutu Safari Lodge has been a favorite with professional wildlife photographers and filmmakers for the past four decades, because it’s simply one of the best places to watch wildlife. Locate us on Google Maps Altitude: 1,646 meters/ 5,400 feet Location Coordinates: E 34.997 S 3.020 UTM: 36S 721925 9665979 Location Approximate distance Approximate drive time Seronera 80 km 2 hours Ngorongoro 90 km 2 hours Distances Karatu 142 km 3-5 hours Arusha 280 km 6-7 hours Manyara 165 km 4 hours Tarangire 235 km 6 hours Lobo 160 km 4-5 hours ● By Road – travelling times above ● By Air: approx. 50 minutes from Arusha Airport. During Dec – April there is a daily scheduled service. May – Nov a minimum of 2 pax required to land at Ndutu. ● Ndutu Airstrip is 1 km from Lodge. Transfer to and from the Lodge are complementary. Getting there ● Airlines: schedules and fares available from: Coastal Aviation: www.coastal.co.tz Air Excel: www.airexcelonline.com Regional Air: www.regionaltanzania.com ● ICAO code = HTND Airstrip ● 1200 m long x 25 m wide details ● Compacted clay, not paved, good drainage ● For details about arriving by private plane please contact: [email protected] Google Map NGORONGORO CONSERVATION AREA ● The Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, located 180 km (110 mi) West of Arusha, in the Crater Highlands area of Tanzania. -

Exhibitors Registered 2021 MASTER.Docx

Registered exhibitors at KARIBU-KILIFAIR 2022 Acacia Farm Lodge, Karatu T5 ITV-Independent Television, Dar es Salaam U58 Adventures Aloft, Arusha U18 Jambiani Villas, Paje T35 Africa Amini Life, Usa River U29 Josera Tanzania, Arusha U52 African Scenic Safaris, Moshi A2 Juakali Crafts / Ngaresero Mountain Lodge Z51 African View (T) Ltd, Arusha L10 Kakkoi Food, Arusha F4 Afromaxx, Uganda/Tanzania R5 KANANGA Trucks, Arusha / Nairobi A50 AG Energies Co. Ltd, Dar es Salaam UR32 Katani Limited, Tanga Z4 Air Excel, Arusha W18 Kendwa Rocks Hotel, Zanzibar P3 Air Tanzania Company, Dar es Salaam U5 Khan’s Barbeque, Arusha F12 AMREF-Flying Doctor, Arusha E2 Kibo Palace Hotel, Arusha B4 Ang’ata Camps & Safari, Arusha A14 Kilimanjaro SAR, Moshi UR22 Applied Technology, Arusha F15 Kilimanjaro Wonders Hotel, Moshi U21 Arusha Medivac Ltd, Arusha V20 Kili Villa Ltd, Arusha T18 Asilia lodges and Camps, Arusha W3 Kitamu Coffee, Arusha F3 Axel Janssens Signature Catering, Arusha T42 Kudu Lodge, Karatu C8 Baobab Beach & Spa, Kenya T6 Kudu Safaris (T) Ltd, Arusha K4 Beau Design, Arusha Z41 Kwanza Collection Company,Dar es Salaam Z8 Bella Ragazza, Dar es Salaam Z9 Lake Chahafi Resort, Uganda S1 Bluebay Hotels, Zanzibar T37 Lake Duluti Lodge Ltd, Arusha T33 Braca Tours and Travel Ltd, Uganda S5 Lavano Travel and Tours, Dar es Salaam P5 Build Mart, Arusha UR30 Lengai Safari Lodge, Karatu W4 Burudika Lodges & Camp, Arusha M1 Locking Solution, Arusha P30 Bush 2 City Adventure Ltd, Arusha P6 Lulu Kitololo Studio, Kenya Z45 Butiama Lodge, Mafia N1 Maasai BBQ, Moshi