Revisit to Functional Classification of Towns in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Diary Birgunj ICD: Nepal's Largest Dry Port

Field Diary Birgunj ICD: Nepal’s Largest Dry Port Sugam Bajracharya Research Fellow, Nepal Economic Forum About the Field Visit In collaboration with CUTS International, Nepal Economic Forum (NEF) conducted a field survey under the study ‘Enabling a Political-Economy Discourse for Multimodal Connectivity in the BBIN Sub-region.’ As a result, a team of enumerators from NEF visited the Birgunj Inland Clearance Depot (ICD), the Birgunj Integrated Check Point (ICP), and the surrounding city of Birgunj in December 2020. The objective of the visit was to make a ground-level assessment of the current scenario of the developments in port infrastructure, trade logistics, and the surrounding infrastructure that might play a pivotal role in the multimodal connectivity of Nepal and the BBIN sub-region. The visit also intended to hold stakeholder consultations to get a view of challenges in daily trade operations. Connectivity to Birgunj ICD and ICP The Birgunj ICD is located in the Parsa district of Province 2. The nearest city, Birgunj, is at a distance of 8 km from the dry port, and the nearest Simara airport is 23.4 km away. The ICP is located right next to the ICD at the Nepal-India border. The city of Birgunj is about 140 km south of Kathmandu and takes about four and a half hours to reach via the Kulekhani-Hetauda route. However, large vehicles like buses and trucks are only allowed to travel the Kathmandu-Birgunj route via the Prithvi Highway, which is about 300 km and takes approximately 8-10 hours. Therefore, a 15-minute direct flight from the Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu to Simara Airport is the fastest option available to travel to Birgunj. -

Social Organization District Coordination Co-Ordination Committee Parsa

ORGANISATION PROFILE 2020 SODCC SOCIAL ORGANIZATION DISTRICT COORDINATION COMMITTEE, PARSA 1 | P a g e District Background Parsa district is situated in central development region of Terai. It is a part of Province No. 2 in Central Terai and is one of the seventy seven districts of Nepal. The district shares its boundary with Bara in the east, Chitwan in the west and Bihar (India) in the south and west. There are 10 rural municipalities, 3 municipalities, 1 metropolitan, 4 election regions and 8 province assembly election regions in Parsa district. The total area of this district is 1353 square kilometers. There are 15535 houses built. Parsa’s population counted over six hundred thousand people in 2011, 48% of whom women. There are 67,843 children under five in the district, 61,998 adolescent girls (10-19), 141,635 women of reproductive age (15 to 49), and 39,633 seniors (aged 60 and above). A large share (83%) of Parsa’s population is Hindu, 14% are Muslim, 2% Buddhist, and smaller shares of other religions’. The people of Parsa district are self- depend in agriculture. It means agriculture is the main occupation of the people of Parsa. 63% is the literacy rate of Parsa where 49% of women and 77% of Men can read and write. Introduction of SODCC Parsa Social Organization District Coordination Committee Parsa (SODCC Parsa) is reputed organization in District, which especially has been working for the cause of Children and women in 8 districts of Province 2. It has established in 1994 and registered in District Administration office Parsa and Social Welfare Council under the act of Government of Nepal in 2053 BS (AD1996). -

Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal

IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 Logistics Capacity Assessment Nepal Country Name Nepal Official Name Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Regional Bureau Bangkok, Thailand Assessment Assessment Date: From 16 October 2009 To: 6 November 2009 Name of the assessors Rich Moseanko – World Vision International John Jung – World Vision International Rajendra Kumar Lal – World Food Programme, Nepal Country Office Title/position Email contact At HQ: [email protected] 1/105 IA LCA – Nepal 2009 Version 1.05 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Country Profile....................................................................................................................................................................3 1.1. Introduction / Background.........................................................................................................................................5 1.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................6 1.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ......................................16 1.4. Customs Information...............................................................................................................................................18 2. Logistics Infrastructure .....................................................................................................................................................33 2.1. Port Assessment .....................................................................................................................................................33 -

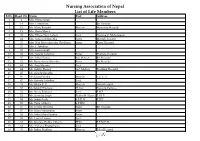

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Integrated Urban Development Project- Siddharthanagar Municipality

Draft Initial Environmental Examination September 2011 NEP: Integrated Urban Development Project- Siddharthanagar Municipality Prepared by the Government of Nepal, Ministry of Physical Planning and Works for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 5 August 2011) Currency unit – Nepalese rupee (NRs/NRe) NRs1.00 = $0.01391 $1.00 = NRs 71.874 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - community building organization CLC - City Level Committees CPHEEO - Central Public Health and Environmental Engineering Organization CTE - Consent to Establish CTO - Consent to Operate DSMC - Design Supervision Management Consultant EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EMP - Environmental Management Plan GRC - Grievance Redress Committee H&S - health and safety IEE - initial environmental examination IPCC - Investment Program Coordination Cell lpcd - liters per capita per day MFF - Multitranche Financing Facility MSW - municipal solid waste NEA - national-level Executing Agency NGO - nongovernmental organization NSC - National level Steering Committee O&M - operation and maintenance PMIU - Project Management and Implementation Unit PSP - private sector participation SEA - State-level Executing Agency SEIAA - State Environment Impact Assessment Authority SIPMIU - State-level Investment Program Management and Implementation Units SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TOR - terms of reference UD&PAD - Urban Development & Poverty Alleviation Department UDD - Urban Development Department ULB - urban local body WEIGHTS AND MEASURES dbA – decibels ha – hectare km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer l – liter m – meter m2 – square meter M3 – cubic meter MT – metric tons MTD – metric tons per day NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

A Connectivity-Driven Development Strategy for Nepal: from a Landlocked to a Land-Linked State

ADBI Working Paper Series A Connectivity-Driven Development Strategy for Nepal: From a Landlocked to a Land-Linked State Pradumna B. Rana and Binod Karmacharya No. 498 September 2014 Asian Development Bank Institute Pradumna B. Rana is an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Binod Karmacharya is an advisor at the South Asia Centre for Policy Studies (SACEPS), Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared for the ADB–ADBI study on “Connecting South Asia and East Asia.” The authors are grateful for the comments received at the Technical Workshop held on 6–7 November 2013. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. “$” refers to US dollars, unless otherwise stated. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Rana, P., and B. -

Short Listed Candidates for the Post

.*,ffix ryryffi-ffiffiWffir@fuffir. rySW{Jrue,€ f,rc, "*,*$,S* S&s#ery W€ryff$,,,SffWryf ryAeW Notice for the Short Listed Candidates applying in the post of "Trainee Assistantrr Details fot Exam: a. 246lestha,2076: Collection of Entrance Card (For Surrounding Candidates). b. 25nJestha, 2076: Collection of Entrance Card 8:00AM to 9:45AM in Exam Center (For Others). (Please carry Original Citizenship Certificate and l passport size photo). Written Test (Exam) : Date : 25'hJesth, 2076 Saurday (8ftJune, 2019). Time : 10:00 AM to 11:30 AM tVenue : Oxford Higher Secondary School, Sukhkhanagar, Butwal, Rupandehi. Paper Weightage : 100 Marks Composition Subjective Questions : 02 questions @ 10 marks = 20 marks Objective Questions : 40 questions @ 02 marks = B0 marks Contents 1,. General Banking Information - 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks 2. Basic Principles & Concept of Accounting - 10 objective questions @2marks = 20 marks 3. Quantitative Aptitude 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks 4. General ISowledge - 10 objective questions @ 2 marks = 20 marks (2 Subjective questions shall be from the fields as mentioned above). NOTE: ,/ I(ndly visit Bank's website for result and interview notice. For Futther Information, please visit : Ffuman Resource Department Shine Resunga Development Bank Limited, Central Office, Maitri Path, But'ural. enblrz- *rrc-tr fffir tarmrnfrur *ffi ffi{" ggffrus gevrcgemmrup w mes'g:iwme ffiAru${ frffi. S4tq t:e w r4r4.q klc S.No. Name of Applicant Address 7 Aakriti Neupane Sainamaina-03, M u reiva RuoanriEh] -

SASEC Road Improvement Project

Social Monitoring Report Semiannual Report (July-December 2018) January 2019 NEP: SASEC Road Improvement Project Prepared by Department of Roads, Project Directorate (ADB), for Ministry of Physical Infrastructure & Transport and the Asian Development Bank. This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. pGovernment of Nepal Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Transport DEPARTMENT OF ROADS Project Directorate (ADB) Bishalnagar, Kathmandu, Nepal CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR CONSTRUCTION SUPERVISION OF SASEC ROADS IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (SRIP) (ADB Loan No.: 3478-NEP) SEMI-ANNUAL REPORT NO. 3 (SOCIAL MONITORING) SASEC Roads Improvement Project Package 1: EWH- Narayanghat Butwal Road, Section I (64.425 Km) Package 2: EWH- Narayanghat Butwal Road, Section II (48.535 Km) Package 3: Bhairahawa – Lumbini - Taulihawa Road, (41.130 Km) (July - December) 2018 Submitted by M/S Korea Engineering Consultants Ltd. Corp.- MEH Consultant (P) Ltd., Kyong Dong Engineering Co. Ltd. JV In association with MULTI – Disciplinary Consultants (P) Ltd. & Seoul, Korea. SOIL Test (P) Ltd. SEMI-ANNUAL (SOCIAL MONITORING) REPORT 3 July - December 2018 Social Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report No. 3 (July - December 2018) NEP: Loan No. 3478 SASEC Road Improvement Project (SRIP) Prepared by: Department of Roads, Project Directorate (ADB), for Ministry of Physical Infrastructure & Transport and the Asian Development Bank. -

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 23-43 the GAZE JOURNAL of TOURISM and HOSPITALITY

The Gaze Journal of Tourism and Hospitality (2021) 12:1, 23-43 THE GAZE JOURNAL OF TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY Th e Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism: A Case Study of Lumbini, Nepal Bhim Bahadur Kunwar Lecturer, Lumbini Buddhist University, Lumbini [email protected] Article History Abstract Received 31 August 2020 Accepted 18 October 2020 Th is research aims to discover and present the impacts of COVID-19 in tourism in the context of Lumbini and its premises. As COVID-19 spread globally, it has created many challenges in health and security, daily lives, the national economy, and the global tourism industry. Th e COVID- 19 outbreak has been considered as the most challenging tragedy that occurred in the world aft er the 2nd world war. Keywords Th e World Health Organization (WHO) had listed Nepal also COVID-19, tourism, as a country with a high-risk zone of COVID-19.Th e travel Lumbini - Nepal, restriction and nationwide lock-down implemented by many insecurity, impacts countries including Nepal have resulted in a stranded traveler’s movement. As the consequences ticket reservation, fl ight services, transportation, hotel, and restaurants were closed and several job losses were registered in the tourism sector. Th e negative eff ects like fear, threat, frustration, and losing the confi dence of tourism entrepreneurs appeared. Th is has brought changes in the tourists’ behavior and their motivation to travel for the next few years. In Lumbini businesses like Corresponding Editor Ramesh Raj Kunwar lodges, hotels, restaurants, and travel offi ces were also severely [email protected] aff ected by the pandemic. -

Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (Muan) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN)

Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (MuAN) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden European Sverige Union "This document has been financed by the Swedish "This publication was produced with the financial support of International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of does not necessarily share the views expressed in this MuAN, NARMIN, ADCCN and UCLG and do not necessarily material. Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the reflect the views of the European Union'; author." Publication Date June 2020 Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal (MuAN) National Association of Rural Municipality in Nepal (NARMIN) Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden Sverige European Union Expert Services Dr. Dileep K. Adhikary Editing service for the publication was contributed by; Mr Kalanidhi Devkota, Executive Director, MuAN Mr Bimal Pokheral, Executive Director, NARMIN Mr Krishna Chandra Neupane, Executive Secretary General, ADCCN Layout Designed and Supported by Edgardo Bilsky, UCLG world Dinesh Shrestha, IT Officer, ADCCN Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... -

Kathmandu NEPAL Area

Development and Operation of Dry Ports in Nepal Sarad Bickram Rana, Executive Director, Nepal Intermodal Transport Development Board (NITDB) Kathmandu, Nepal 1 Presentation Overview • Key Information on trade and transit situation • Policy Guidelines • Institutional Arrangements • Related Act and Regulations • Expected Benefit • Some Major Problems • Summary 2 NEPAL Area : 147,181 Sq. Km. Population: 26.5 Mill. GDP Per capita : 700 $ Kathmandu 3 Foreign Trade Situation Status of Nepal as per Doing 177th out of 189 Business Report Export Cost per container US$ 2,400 Export Time 42 days Import cost per container US$ 2,295 Import Time 39 days Stream Share of Total Trade(2012/13) Export 11% Import 89% 100% India 66% Overseas 34 % 100% 4 Transit Provision Through Treaty of Transit between Nepal and India • Gateway Port (Out of major ports Kolkata Port is a designated port ) • 26 Border Crossing point • 1 rail head Through Rail-Service Agreement between Nepal and India • 1 rail based Through Nepal-China Agreement • 6 Border crossing point 5 Trade Corridors (Major) Yari Nechung Rasuwa Kimathanka Olangchungola Dryports/ Inland Clearance Depots under operations Dryport under construction Proposed for future construction 6 Transport Infrastructure (2013) Roads Local Roads (50,943 Km) Strategic Roads (11,636 Km) Railways Jayanagar (India) - Janakpur (Nepal) Raxaul (India) – Birgunj (Nepal) (51 KM) (5 KM) Airfields 48 Nos. (registered) Dryports Road based (3+1) Rail based(1) 7 Policies for Development of Dry ports • Eighth Five Year Plan (1992-97) -

Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Urbanization in Siddharthanagar, Nepal

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Economics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 7-24-2020 ASSESSING THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF URBANIZATION IN SIDDHARTHANAGAR, NEPAL Bishal Raj Khanal Universitty of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/econ_etds Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Khanal, Bishal Raj. "ASSESSING THE ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS OF URBANIZATION IN SIDDHARTHANAGAR, NEPAL." (2020). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/econ_etds/113 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Economics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Bishal Raj Khanal Candidate Economics Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Alok K Bohara , Chairperson Andrew Goodkind Sarah S Stith Jingjing Wang i Assessing the Environmental Impacts of Urbanization in Siddharthanagar Nepal BY Bishal Raj Khanal B.Arch., 2014 MLA, 2018 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts Economics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2020 ii Dedication To the unyielding researchers; and to everyone who is saving lives in the Corona pandemic. and to my wife, Prakriti and to my family and friends. iii Acknowledgment I am grateful to my Chair, Dr. Alok K. Bohara, who has been a continuous source of motivation to me. I am thankful to my committee Dr.