Oswald: Return of the King

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Origins of Lordship

THE ANCIENT ORIGINS OF THE LORDSHIP OF BOWLAND Speculation on Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norse and Brythonic roots William Bowland The standard history of the lordship of Bowland begins with Domesday. Roger de Poitou, younger son of one of William the Conqueror’s closest associates, Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, is recorded in 1086 as tenant-in-chief of the thirteen manors of Bowland: Gretlintone (Grindleton, then caput manor), Slatebourne (Slaidburn), Neutone (Newton), Bradeforde (West Bradford), Widitun (Waddington), Radun (Radholme), Bogeuurde (Barge Ford), Mitune (Great Mitton), Esingtune (Lower Easington), Sotelie (Sawley?), Hamereton (Hammerton), Badresbi (Battersby/Dunnow), Baschelf (Bashall Eaves). William Rufus It was from these holdings that the Forest and Liberty of Bowland emerged sometime after 1087. Further lands were granted to Poitou by William Rufus, either to reward him for his role in defeating the army of Scots king Malcolm III in 1091-2 or possibly as a consequence of the confiscation of lands from Robert de Mowbray, Earl of Northumbria in 1095. 1 As a result, by the first decade of the twelfth century, the Forest and Liberty of Bowland, along with the adjacent fee of Blackburnshire and holdings in Hornby and Amounderness, had been brought together to form the basis of what became known as the Honor of Clitheroe. Over the next two centuries, the lordship of Bowland followed the same descent as the Honor, ultimately reverting to the Crown in 1399. This account is one familiar to students of Bowland history. However, research into the pattern of land holdings prior to the Norman Conquest is now beginning to uncover origins for the lordship that predate Poitou’s lordship by many centuries. -

An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2017 An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England Julie Polcrack Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Polcrack, Julie, "An Analysis of the Metal Finds from the Ninth-Century Metalworking Site at Bamburgh Castle in the Context of Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metalworking in Middle- and Late-Saxon England" (2017). Master's Theses. 1510. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/1510 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND by Julie Polcrack A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The Medieval Institute Western Michigan University August 2017 Thesis Committee: Jana Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Robert Berkhofer, Ph.D. Graeme Young, B.Sc. AN ANALYSIS OF THE METAL FINDS FROM THE NINTH-CENTURY METALWORKING SITE AT BAMBURGH CASTLE IN THE CONTEXT OF FERROUS AND NON-FERROUS METALWORKING IN MIDDLE- AND LATE-SAXON ENGLAND Julie Polcrack, M.A. -

Saint Jordan of Bristol: from the Catacombs of Rome to College

THE BRISTOL BRANCH OF THE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION LOCAL HISTORY PAMPHLETS SAINT JORDAN OF B�ISTOL: FROM THE CATACOMBS OF ROME Hon. General Editor: PETER HARRIS TO COLLEGE GREEN AT BRISTOL Assistant General Editor: NORMA KNIGHT Editorial Advisor: JOSEPH BETTEY THE CHAPEL OF ST JORDAN ON COLLEGE GREEN Intercessions at daily services in Bristol Cathedral conclude with the Saint Jordan of Bristol: from the Cataconibs of Rome to College Green at following act of commitment and memorial: Bristol is the one hundred and twentieth pamphlet in this series. We commit ourselves, one another and our whole life to Christ David Higgins was Head of the Department of Italian Studies at the our God ... remembering all who have gone before us in faith, and University of Bristol until retirement in 1995. His teaching and research in communion with Mary, the Apostles Peter and Paul, Augustine embraced the political, cultural and linguistic history of Italy in its and Jordan and all the Saints. Mediterranean and European contexts from the Late Roman Period to the Patron Saints of a city, as opposed to a country, are a matter of local Middle Ages, while his publications include Dante: The Divine Comedy choice and tradition - in England he or she is normally the patron saint (Oxford World's Classics 1993) as well as articles in archaeological journals of the city's Cathedral: St Paul (London), St Augustine (Canterbury), St Mary on the Roman and Anglo-Saxon periods of the Bristol area, and in this and St Ethelbert (Hereford); while St David of Wales and St Andrew of series The History of the Bristol Region in the Roman Period and The· Scotland gave their names to the cities in question. -

The Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Mercia and the Origins and Distribution of Common Fields*

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the origins and distribution of common fields* by Susan Oosthuizen Abstract: This paper aims to explore the hypothesis that the agricultural layouts and organisation that had de- veloped into common fields by the high middle ages may have had their origins in the ‘long’ eighth century, between about 670 and 840 AD. It begins by reiterating the distinction between medieval open and common fields, and the problems that inhibit current explanations for their period of origin and distribution. The distribution of common fields is reviewed and the coincidence with the kingdom of Mercia noted. Evidence pointing towards an earlier date for the origin of fields is reviewed. Current views of Mercia in the ‘long’ eighth century are discussed and it is shown that the kingdom had both the cultural and economic vitality to implement far-reaching landscape organisation. The proposition that early forms of these field systems may have originated in the ‘long’ eighth century is considered, and the paper concludes with suggestions for further research. Open and common fields (a specialised form of open field) endured in the English landscape for over a thousand years and their physical remains still survive in many places. A great deal is known and understood about their distribution and physical appearance, about their man- agement from their peak in the thirteenth century through the changes of the later medieval and early modern periods, and about how and when they disappeared. Their origins, however, present a continuing problem partly, at least, because of the difficulties in extrapolating in- formation about such beginnings from documentary sources and upstanding earthworks that record – or fossilise – mature or even late field systems. -

ND March 2020.Pdf

ELLAND All Saints , Charles Street, HX5 0LA A Parish of the Soci - ety under the care of the Bishop of Wakefield . Serving Tradition - alists in Calderdale. Sunday Mass 9.30am, Rosary/Benediction usually last Sunday, 5pm. Mass Tuesday, Friday & Saturday, parish directory 9.30am. Canon David Burrows SSC , 01422 373184, rectorofel - [email protected] BATH Bathwick Parishes , St.Mary’s (bottom of Bathwick Hill), BROMLEY St George's Church , Bickley Sunday - 8.00am www.ellandoccasionals.blogspot.co.uk St.John's (opposite the fire station) Sunday - 9.00am Sung Mass at Low Mass, 10.30am Sung Mass. Daily Mass - Tuesday 9.30am, St.John's, 10.30am at St.Mary's 6.00pm Evening Service - 1st, Wednesday 9.30am, Holy Hour, 10am Mass Friday 9.30am, Sat - FOLKESTONE Kent , St Peter on the East Cliff A Society 3rd &5th Sunday at St.Mary's and 2nd & 4th at St.John's. Con - urday 9.30am Mass & Rosary. Fr.Richard Norman 0208 295 6411. Parish under the episcopal care of the Bishop of Richborough . tact Fr.Peter Edwards 01225 460052 or www.bathwick - Parish website: www.stgeorgebickley.co.uk Sunday: 8am Low Mass, 10.30am Solemn Mass. Evensong 6pm parishes.org.uk (followed by Benediction 1st Sunday of month). Weekday Mass: BURGH-LE-MARSH Ss Peter & Paul , (near Skegness) PE24 daily 9am, Tues 7pm, Thur 12 noon. Contact Father Mark Haldon- BEXHILL on SEA St Augustine’s , Cooden Drive, TN39 3AZ 5DY A resolution parish in the care of the Bishop of Richborough . Jones 01303 680 441 http://stpetersfolk.church Saturday: Mass at 6pm (first Mass of Sunday)Sunday: Mass at Sunday Services: 9.30am Sung Mass (& Junior Church in term e-mail :[email protected] 8am, Parish Mass with Junior Church at1 0am. -

Gendered Networks and Communicability in Medieval

GENDERED NETWORKS AND COMMUNICABILITY IN MEDIEVAL HISTORICAL NARRATIVES APREPRINT S D Prado, S R Dahmen A L C Bazzan, Instituto de F´ısica Instituto de Informatica´ Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Porto Alegre, 91501-970, Brazil Porto Alegre, 91501-970, Brazil M MacCarron J Hillner Department of Digital Humanities Department of History University College Cork University of Sheffield Cork, T12 YN60, Ireland Sheffield, S3 7RA, UK February 5, 2020 ABSTRACT One of the defining representations of women from medieval times is in the role of peaceweaver, that is, a woman was expected to ’weave’ peace between warring men. The underlying assumption in scholarship on this topic is that female mediation lessens male violence. This stance can however be questioned since it may be the result of gender-based peace and diplomacy models that relegate women’s roles to that of conduits between men. By analysing the concept of communicability and relevance of certain nodes in complex networks we show how our sources afford women more complex and nuanced social roles. As a case study we consider a historical narrative, namely Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People, which is a history of Britain from the first to eighth centuries AD and was immensely popular all over Europe in the Middle Ages. Keywords Gendered Networks · Communicability · Node Relevance · Medieval History 1 Introduction In the last few years we have witnessed an explosion in the use of networks as a quantitative tool with which one may analyse and quantify interpersonal relationships in human societies [1, 2]. -

Constructing Early Anglo-Saxon Identity in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles

Chapter 7 Constructing Early Anglo-Saxon Identity in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles Courtnay Konshuh The chronicle compiled at King Alfred’s court after 891 was part of his educa- tional reform and was also part of an attempt to create a common national identity for the English. This can be seen in the contemporary annals (i.e. from 871 to 891), but the large body of annals drawn together from diverse sources for the preceding nine centuries shows this same focus. The earlier annals, while not necessarily compiled at the same time, were selected and manipu- lated with the same goals, and are organised thematically into annals which explore Britannia’s roots as a Roman colony, its development as a Christian nation, and the adventus of the Germanic tribes. Barbara Yorke has shown some of these accounts to be semi-historical or mythological, but they are jux- taposed with historically accurate descriptions. While the early annals have a different compilation context than those which document Alfred’s reign, they were nonetheless selected, organised and inflated in order to legitimise the line of Cerdic and bestow authority on Alfred as well as his descendants. In this, they follow the same model as later annals in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles.1 In light of recent research, it seems well established that the compilation of the “Common Stock” or “Alfredian Chronicle” (i.e. the annals to 891 common to most Anglo-Saxon Chronicles) was a courtly endeavour and that the exemplar for the earliest A-manuscript was a product of King Alfred’s scholarly circle.2 While Alfred’s personal involvement in this may not have been particularly large,3 the political thought of his circle of scholars can be detected throughout the annals. -

Saint Enflaeda, Abbess of Whitby

Eanflæd Eanflæd (19 April 626 – after 685, also known as En- King Penda of Mercia, the victor of Maserfield, dom- fleda) was a Kentish princess, queen of Northumbria[1] inated central Britain and Oswiu was in need of sup- and later, the abbess of an influential Christian monastery port. Marriage with Eanflæd would provide Kentish, in Whitby, England. She was the daughter of King Edwin and perhaps Frankish, support, and any children Oswiu of Northumbria and Æthelburg, who in turn was the and Eanflæd might have would have strong claims to daughter of King Æthelberht of Kent. In or shortly af- all of Northumbria.[7] The date of the marriage is not ter 642 Eanflæd became the second wife of King Oswiu recorded.[8] [1][2] of Northumbria. After Oswiu’s death in 670, she If Oswiu’s goal in marrying Eanflæd was the peaceful ac- retired to Whitby Abbey, which had been founded by ceptance of his rule in Deira, the plan was unsuccess- Hilda of Whitby. Eanflæd became the abbess around 680 ful. By 644 Oswine, Eanflæd’s paternal second cousin, and remained there until her death. The monastery had was ruling in Deira.[9] In 651 Oswine was killed by one strong association with members of the Northumbrian of Oswiu’s generals. To expiate the killing of his wife’s royal family and played an important role in the estab- kinsman, Oswiu founded Gilling Abbey at Gilling where lishment of Roman Christianity in England. prayers were said for both kings.[10] 1 Birth, baptism, exile 3 Children, patron of Wilfred, sup- Eanflæd’s mother had been raised as a Christian, but her porter of Rome father was raised as an Anglo-Saxon pagan and he re- mained uncommitted to the new religion when she was With varying degrees of certainty, Eanflæd’s children born on the evening before Easter in 626 at a royal res- with Oswiu are identified as Ecgfrith, Ælfwine, Osthryth, idence by the River Derwent. -

The Demo Version

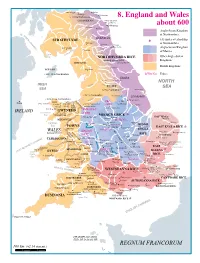

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c. -

Northumbria University Northumbria University CASE STUDY

Northumbria University STUDY CASE Northumbria University has two a million visitors each year and large city-based campuses in renowned for its buzzing nightlife. Newcastle and uses SafeZone Given the university’s city-centre locations, alerts are typically from as part of its integrated users worried about suspicious approach to help promote people or feeling threatened. and assure student and staff SafeZone enables the Northumbria safety within this busy urban security team to intervene more SafeZoneApp.com environment. quickly, to offer support, and to prevent incidents from escalating. “SafeZone allows us to SafeZone has also helped save lives Northumbria University is home to respond more quickly and by accelerating first-aid support to almost 32,000 students and staff and victims suffering from cardiac arrest, in many cases to prevent was the first university in Europe to stroke, severe choking or an extreme incidents from escalating. adopt SafeZone®. The service is now allergic reaction. used across all its Newcastle facilities, Northumbria’s commitment central London campus and a new to safety and security is recently announced Amsterdam site. also helping us to recruit SafeZone is an essential element in more overseas students Northumbria’s integrated approach to security that includes the university who are increasingly having its own dedicated crime being drawn towards prevention team and full-time Newcastle and our city- police officer. based campuses,” Newcastle is one of the UK’s liveliest JOHN ANDERSON cities, attracting over a quarter of Head of Security at Northumbria University, Newcastle SafeZone solution Benefits and outcomes Northumbria University has an active in their profile. -

An Analysis of Eddius Stephanus' Life of Wilfrid: the Struggle for Authority Over the English Church in the Late Seventh Century

Intro to the Early Middle Ages Fall 2000 Stefanie Weisman Prof. Kosto An Analysis of Eddius Stephanus' Life of Wilfrid: The Struggle for Authority Over the English Church In the Late Seventh Century In the year 664,1 a multitude of English bishops, abbots and priests -- as well as Oswiu and Alhfrith, the kings of Northumbria -- convened at the Abbey of Whitby.2 Their purpose, according to the monk Eddius Stephanus in his Life of Wilfrid, was to decide when Easter should be celebrated.3 At the time, there were two ways of calculating the date of this holiday. One method was sanctioned by the Apostolic See in Rome and used by clerics throughout Christendom.4 The churchmen of northern England, Ireland and Scotland, however, determined the date in a slightly different manner.5 Although the two methods produced dates that varied by no more than a day,6 this was enough to merit the gathering of this synod in Whitby. In Stephanus’ Life, King Oswiu asks the question that was at the heart of the matter for those assembled at the abbey: “which is greater in the Kingdom of Heaven, Columba or the apostle Peter?”7 The Irish saint Columba represented the Celtic tradition of Christianity and its rules, such as the unique way of calculating Easter, which had dominated the Church of northern England for several decades.8 Saint Peter, who was the first bishop of Rome, symbolized the distant Apostolic See and its laws and practices.9 Oswiu’s question, therefore, implies that the churchmen in Whitby had to make the following decision: would the English Church be subject to Rome and obey the tenets of the Pope, or would it remain relatively independent of the Holy See and follow the Celtic discipline? The synod resolved to celebrate Easter according to the Roman method.10 Their decision was based largely on the belief that the Messiah had granted primacy over all of Christendom to the Apostolic See. -

Counting Sleep? Critical Reflections on a UK National Sleep Strategy

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Meadows, Robert, Nettleton, Sarah, Hine, Christine and Ellis, Jason (2021) Counting sleep? Critical reflections on a UK national sleep strategy. Critical Public Health, 31 (4). pp. 494-499. ISSN 0958-1596 Published by: Taylor & Francis URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2020.1744525 <https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2020.1744525> This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/46010/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html This document may differ from the final, published version of the research and has been made available online in accordance with publisher policies. To read and/or cite from the published version of the research, please visit the publisher’s website (a subscription may be required.) Counting Sleep? Critical reflections on a UK national sleep strategy.