Clinical Audit: a Simple Guide for NHS Boards & Partners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Management Review

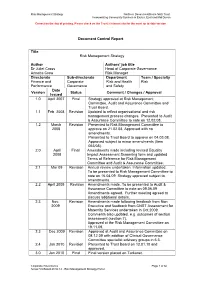

Risk Management Strategy Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust Incorporating Community Services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon Correct on the day of printing. Please check on the Trust’s internet site for the most up to date version Document Control Report Title Risk Management Strategy Author Authors’ job title Dr Juliet Cross Head of Corporate Governance Annette Crew Risk Manager Directorate Sub-directorate Department Team / Specialty Finance and Corporate Risk and Health Risk Performance Governance and Safety Date Version Status Comment / Changes / Approval Issued 1.0 April 2007 Final Strategy approved at Risk Management Committee, Audit and Assurance Committee and Trust Board. 1.1 Feb. 2008 Revision Updated to reflect organisational and risk management process changes. Presented to Audit & Assurance Committee to note on 12.02.08. 1.2 March Revision Presented to Risk Management Committee to 2008 approve on 21.02.08. Approved with no amendments. Presented to Trust Board to approve on 04.03.08. Approved subject to minor amendments (Item 053/08). 2.0 April Final Amendments made including revised Equality 2008 Impact Assessment Screening form and updated Terms of Reference for Risk Management Committee and Audit & Assurance Committee. 2.1 Mar 09 Revision Annual review undertaken. Information updated. To be presented to Risk Management Committee to note on 16.04.09. Strategy approved subject to amendments. 2.2 April 2009 Revision Amendments made. To be presented to Audit & Assurance Committee to note on 09.06.09 Amendments agreed. Further meeting agreed to discuss additional details. 2.3 Nov. Revision Amendments made following feedback from Non 2009 Executive and feedback from CNST Assessment for Maternity Services undertaken in Oct.2009. -

Clinical Audit/Quality Improvement Projects Guidance for Professional

Clinical Audit/Quality Improvement Projects Guidance For Professional Competence Scheme Prepared by Faculty of Public Health Medicine December 2012 1 KEY POINTS ON AUDIT FOR PUBLIC HEALTH . This document is produced by the Faculty of Public Health Medicine Ireland (FPHMI) to support and guide participants of the FPHMI Professional Competence Scheme (PCS) to achieve their requirement of completing one clinical audit / quality improvement project each year. This document is a guide for doctors practising public health medicine and who are either on the Specialist or General Division of the Register . All doctors must participate in professional competence . Each doctor must define his/her scope of practice . All doctors whose practice include both clinical and non‐clinical work should engage in both clinical audit and other quality improvement practices relevant to their scope of practice . Audit can be at individual, team, departmental or national level . Each doctor must actively engage in clinical audit / systematic quality improvement activity that relates directly to their practice. ‘The Medical Council’s Framework for Maintenance of Professional Competence Activities’ sets one clinical audit per year as the minimum target. The time spent on completing the audit is accounted for separately from other Continuing Professional Development (CPD) activities. It is estimated that the completion of one clinical audit will take approximately 12 hours of activity. The main challenges in undertaking audit in public health practice include o Lack of explicit criteria against which to measure audit o Timeframes for measuring outcomes which can be prolonged and thus process measures are more readily measured Can’t seem to format this box which is smaller than the text o Changing public health work programmes in Departments . -

Onsite Guide

A HIA 3 8T H A N N U A L C O N F E R E N C E ONSITE GUIDE SPONSORED BY Scan to download the AHIA Conference App www.ahia.org TABLE OF CONTENTS AHIA MISSION & VISION AHIA Mission and Vision . 3 & VISION AHIA MISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE Hotel Floor Plan & Site Map . 4-5 Welcome . 5 Schedule of Events by Day . 6-15 AHIA Board of Directors & Conference MISSION STATEMENT Planning Committee . 17 The Association of Healthcare Internal Auditors provides leadership Exhibit Hall Hours & Social Events Schedule . 18-19 and advocacy to advance the healthcare internal audit profession AHIA Conference Tracks . 20-21 globally by facilitating relevant education, resources, certification 2020 Save the Date . 21 and networking opportunities. Conference Schedule Sunday, September 15 . 22-30 VISION STATEMENT Monday, September 16 . 31-44 To be the premier association for healthcare internal auditing. Tuesday, September 17 . 45-59 Founded in 1981, the Association of Healthcare Internal Auditors Wednesday, September 18 . 61-67 (AHIA) is a network of experienced healthcare internal auditing Sponsors . 68-69 professionals who come together to share tools, knowledge and Exhibitor Hours & Drawing . .. 70 insight on how to assess and evaluate risk within a complex and dynamic healthcare environment. AHIA is an advocate for the Exhibitor Floor Plan . 71 profession, continuing to elevate and champion the strategic Exhibitor Listing . 72-82 importance of healthcare internal auditors with executive CPE Certification . 85 management and the Board. If you have a stake in healthcare governance, risk management and internal controls, AHIA is CHIAP™ Certificants . 86–88 your one-stop resource. -

Principles of Surgical Audit

Principles of I Surgical Audit How to Set Up a Prospective 1 Surgical Audit Andrew Sinclair and Ben Bridgewater Key points • Clinical audit can be prospective and/or • A clinical department benefits from a clear audit retrospective. plan. • Audit information can be obtained from • Clinical audit improves patient outcome. national, hospital, and surgeon-specific data. Much of the experience we draw on comes from cardiac Introduction surgery, where there is a long history of structured data collection, both in the United States and in the United Clinical audit is one of the “keystones” of clinical govern- Kingdom. This was initially driven by clinicians [1–3,5], ance. A surgical department that subjects itself to regu- but more recently has been influenced by politicians and lar and comprehensive audit should be able to provide the media [6,7]. Cardiac surgery is regarded as an easy data to current and prospective patients about the qual- specialty to audit in view of the high volume and pro- ity of the services it provides, as well as reassurance to portion of a single operation coronary artery bypass those who pay for and regulate health care. Well-organ- graft (CABG) in most surgeons practice set against a ized audit should also enable the clinicians providing small but significant hard measurement end point of services to continually improve the quality of care they mortality (which is typically approximately 2%). deliver. There are many similarities between audit and research, but historically audit has often been seen as the “poor relation.” For audit to be meaningful and useful, it Why conduct prospective audit? must, like research, be methodologically robust and have sufficient “power” to make useful observations; it would There are a number of reasons why clinicians might be easy to gain false reassurance about the quality of care decide to conduct a clinical audit as given in Table 1.1. -

Toolkit to Develop and Strengthen Medical Audit Systems

Toolkit to Develop and Strengthen Medical Audit Systems Practical Guide by Implementers for Implementers December 2017 2017 심사평 메뉴얼북 표지.indd 2 17. 11. 29. 오후 8:26 2017 심사평 메뉴얼북 표지.indd 3 17. 11. 29. 오후 8:26 Toolkit to Develop and Strengthen Medical Audit Systems Practical Guide by Implementers for Implementers December 2017 2017 심사평 메뉴얼북 내지 책.indb 1 17. 11. 29. 오후 8:39 THIS GUIDE WAS PRODUCED by the Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage (JLN), an innovative network of practitioners and policymakers from around the globe who engage in practitioner-to-practitioner learning and collaboratively develop practical tools to help countries work toward universal health coverage. For inquiries about this guide or other related JLN activities, please contact the JLN at [email protected]. This work was funded by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation and by the Government of South Korea. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations. Note: This is the first release of the Medical Audits Toolkit. The toolkit has been reviewed by the participants of JLN’s Medical Audits collaborative, under which the product was developed. Attempts have been made to have the toolkit reviewed by external experts, such as medical audit professionals. A more rigorous review by external experts, along with feedback from countries will be incorporated to make it a comprehensive guide for use by countries looking to strengthen their medical audit systems. Revised version(s) of the toolkit will be available at www.jointlearningnetwork.org. -

Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening

. Cultivating Accountability for health systems strengthening Series of Guides for Enhanced Governance of the Health Sector and Health Institutions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries JUNE 2014 Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 4 Introduction . 5 Purpose and Audience for the Guides . 6 Governing Practice—Cultivating Accountability . 8 Your Personal Accountability . 10 Accountability of Your Organization to its Stakeholders . 11 Internal Accountability in Your Organization . 12 Accountability of Health Providers and Health Workers . 13 Managing Performance . 14 Sharing Information . 15 Developing Social Accountability . 17 Using Technology to Support Accountability . 20 Smart Oversight . 21 Appendix: Transparency and Accountability Tools . .. 22 Accreditation . 22 Community Scorecard . 22 Citizen Report Cards . 23 Participatory Budgeting . 23 Independent Budget Analysis . 24 Public Expenditure Tracking Survey . 24 Social Audit .. 24 Citizen’s Charter . 24 Public Hearings . 24 E-Governance . 25 Community Radio . 25 Community-Based Monitoring of Primary Healthcare Providers in Uganda . 26 References and Resources . 27 Transparency . 27 Accountability . 27 Want To Learn More? . 28 Funding was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-11-00015. The contents are the responsibility of the Leadership, Management, and Governance Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 4 Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening Acknowledgements This work was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Leadership, Management, and Governance (LMG) Project . The LMG Project team thanks the staff of the USAID Office of Population and Reproductive Health, in particular, the LMG Project Agreement Officer’s Representative and her team for their constant encouragement and support . -

Clinical Audit: a Simplified Approach Mansoor Dilnawaz, Hina Mazhar, Zafar Iqbal Shaikh

Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists 2012; 22 (4):358-362. Review Article Clinical audit: A simplified approach Mansoor Dilnawaz, Hina Mazhar, Zafar Iqbal Shaikh Department of Dermatology, Military Hospital (MH), Rawalpindi Abstract A clinical audit measures practice against standards and performance. Unlike research which poses the question, “what is the right thing to do?” clinical audit asks are we doing the right thing in the right way? An approach for understanding a clinical audit is provided. A basic clinical audit example of a case note audit is presented. A simplified template to help the beginners is included. Key words Clinical audit. Introduction and steps of clinical audit We should determine what we are trying to measure and define gold standards. The next Audit is a key component of clinical stage is about setting the standards. Criteria are governance, which aims to ensure that the those aspects of care that we wish to examine. patients receive high standard and best quality Standards are the pre-stated or implicit levels care.1,2 It is important that health professionals of success that we wish to achieve. The are given protected and adequate time to standards are based on the local, national or perform clinical audit.4,5,6,7 Clinical audit runs international guidelines. They should be in a cycle and aims to bring about incremental relevant to our practice. A couple of example improvement in health care. Guidelines and of the sources includes National Institute of standards are set according to perceived Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the British importance and performance is then measured Association of Dermatologists (B.A.D) web against these standards.8,9,10 . -

Report on the Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory

THE ECONOMICS OF PATIENT SAFETY IN PRIMARY AND AMBULATORY CARE Flying blind The Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory Care Flying blind 1 │ This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. The Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory Care © OECD 2018 2 │ Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 3 Key messages .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. This report makes the economic case for safety in the primary and ambulatory care sector ........ 8 1.2. Safety -

Clinical Audit: a Comprehensive Review of the Literature

CENTRE FOR CLINICAL GOVERNANCE RESEARCH Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature The Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health The Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health undertakes strategic research, evaluations and research-based projects of national and international standing with a core interest to investigate health sector issues of policy, culture, systems, governance and leadership. Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature First produced 2009 by the Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052. © Travaglia J, Debono D, 2009 This report is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without the written permission of the copyright owners and the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Title: Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature 1. Literature review method. 2. I. Travaglia J, II. Debono, D. III. University of New South Wales. Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health. Centre for Clinical Governance Research, University of New South Wales, Sydney Australia http://clingov.med.unsw.edu.au Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health, UNSW 2009 i Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature Duration of project February to May 2009 Search period 1950 to May 2009 Key words searched Clinical Audit Databases searched Medline from 1950 Embase from 1980 CINAHL from 1982 Criteria applied Phrase Contact details Contact: Jo Travaglia Email: [email protected] Telephone: 02 9385 2594 Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health Faculty of Medicine University of New South Wales Sydney NSW 2052 Australia Centre for Clinical Governance Research in Health, UNSW 2009 ii Clinical audit: a comprehensive review of the literature CONTENTS 1. -

The Quality of GP Diagnosis and Referral Catherine Foot Chris Naylor Candace Imison

Research paper The quality of GP diagnosis Authors Catherine Foot and referral Chris Naylor Candace Imison An Inquiry into the Quality of General Practice in England The quality of GP diagnosis and referral Catherine Foot Chris Naylor Candace Imison This paper was commissioned by The King’s Fund to inform the Inquiry panel. The views expressed are those of the authors and not of the panel. Contents Executive summary 3 1 Introduction 7 Context 7 Methods 9 2 The quality of diagnosis in general practice in England 11 What is the role of general practice in diagnosis? 11 High-quality diagnosis in general practice – what does it look like? 13 The current quality of diagnosis in general practice 15 Approaches towards quality improvement 22 Key messages 25 3 The quality of referral in general practice in England 27 What is a GP referral? 27 High-quality referral – what does it look like? 27 The quality of current GP referral practices 32 Approaches towards quality improvement in referral 45 Key messages 48 4 Discussion and conclusions 50 Key findings 50 Recommendations for approaches to improvement 51 Potential quality measures 52 Conclusion 54 Appendices Appendix A: Effective interventions 55 Appendix B: Case study 57 Appendix C: Search terms used in literature review 62 References 63 2 The King’s Fund 2010 Executive summary This report forms part of the wider inquiry into the quality of general practice in England commissioned by The King’s Fund, and focuses specifically on the quality of diagnosis and referral. The report: ■ describes what ‘good’ looks like for diagnosis and referral within primary care ■ describes what is known about the current quality of referral and diagnosis in general practice ■ identifies evidence-based means of improving the quality of GP diagnosis and referral ■ considers the potential for quality measures of diagnosis and referral within primary care. -

Audit Example

West of Scotland Region Greater Glasgow Primary Care Trust Ideas for Audit A practical guide to audit and significant event analysis for general practitioners Paul Bowie Dr Alison Garvie Dr John McKay Associate Advisers NHS Education for Scotland Telephone: 0141 223 1463 E-mail: [email protected] Additional material and advice provided by: Drs Linsey Semple, Janice Oliver & Douglas Murphy [PILOT EDITION – NOVEMBER 2004] 1 CONTENTS Introduction Section ONE AUDIT METHOD The Audit Cycle Choosing an Audit Topic Undertaking and Reporting an Audit Project Methods of Data Collection Peer Assessment of Completed Audit Projects Sampling Section TWO SUGGESTED AUDIT TOPICS Core Chronic Disease Audits Workload & Administration Audits Miscellaneous Audits Section THREE SIGNIFICANT EVENT ANALYSIS The SEA Technique Writing a Significant Event Analysis Report SEA Case Studies Peer Assessment of SEA SEA Proforma APPENDICES Marking Schedule (Audit) Assessment Schedule (SEA) Published Sampling Paper & Chart 2 Introduction This booklet was produced in response to the many requests from health care practitioners and staff for a list of ideas for audit that can be easily applied in general practice. An extensive range of clinical and workload topics is covered and over 100 potential audits are described. A practical guide to basic audit method and the significant event analysis technique is also included. Additional guidance is provided on how to compile simple written reports on the completion of each activity. The language surrounding both approaches to quality improvement can be unnecessarily confusing and potentially off-putting. Hopefully we can shed some light by explaining the various terms used in a straightforward way whilst illustrating this with practical every day examples. -

Exploring Variation in the Use of Feedback from National Clinical

Alvarado et al. BMC Health Services Research (2020) 20:859 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05661-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Exploring variation in the use of feedback from national clinical audits: a realist investigation Natasha Alvarado1* , Lynn McVey1, Joanne Greenhalgh2, Dawn Dowding3, Mamas Mamas4, Chris Gale5, Patrick Doherty6 and Rebecca Randell7 Abstract Background: National Clinical Audits (NCAs) are a well-established quality improvement strategy used in healthcare settings. Significant resources, including clinicians’ time, are invested in participating in NCAs, yet there is variation in the extent to which the resulting feedback stimulates quality improvement. The aim of this study was to explore the reasons behind this variation. Methods: We used realist evaluation to interrogate how context shapes the mechanisms through which NCAs work (or not) to stimulate quality improvement. Fifty-four interviews were conducted with doctors, nurses, audit clerks and other staff working with NCAs across five healthcare providers in England. In line with realist principles we scrutinised the data to identify how and why providers responded to NCA feedback (mechanisms), the circumstances that supported or constrained provider responses (context), and what happened as a result of the interactions between mechanisms and context (outcomes). We summarised our findings as Context+Mechanism = Outcome configurations. Results: We identified five mechanisms that explained provider interactions with NCA feedback: reputation, professionalism, competition, incentives, and professional development. Professionalism and incentives underpinned most frequent interaction with feedback, providing opportunities to stimulate quality improvement. Feedback was used routinely in these ways where it was generated from data stored in local databases before upload to NCA suppliers.