Clinical Governance in Primary Care; Principles, Prerequisites and Barriers: a Systematic Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Management Review

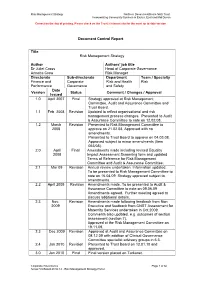

Risk Management Strategy Northern Devon Healthcare NHS Trust Incorporating Community Services in Exeter, East and Mid Devon Correct on the day of printing. Please check on the Trust’s internet site for the most up to date version Document Control Report Title Risk Management Strategy Author Authors’ job title Dr Juliet Cross Head of Corporate Governance Annette Crew Risk Manager Directorate Sub-directorate Department Team / Specialty Finance and Corporate Risk and Health Risk Performance Governance and Safety Date Version Status Comment / Changes / Approval Issued 1.0 April 2007 Final Strategy approved at Risk Management Committee, Audit and Assurance Committee and Trust Board. 1.1 Feb. 2008 Revision Updated to reflect organisational and risk management process changes. Presented to Audit & Assurance Committee to note on 12.02.08. 1.2 March Revision Presented to Risk Management Committee to 2008 approve on 21.02.08. Approved with no amendments. Presented to Trust Board to approve on 04.03.08. Approved subject to minor amendments (Item 053/08). 2.0 April Final Amendments made including revised Equality 2008 Impact Assessment Screening form and updated Terms of Reference for Risk Management Committee and Audit & Assurance Committee. 2.1 Mar 09 Revision Annual review undertaken. Information updated. To be presented to Risk Management Committee to note on 16.04.09. Strategy approved subject to amendments. 2.2 April 2009 Revision Amendments made. To be presented to Audit & Assurance Committee to note on 09.06.09 Amendments agreed. Further meeting agreed to discuss additional details. 2.3 Nov. Revision Amendments made following feedback from Non 2009 Executive and feedback from CNST Assessment for Maternity Services undertaken in Oct.2009. -

Clinical Audit: a Simple Guide for NHS Boards & Partners

Clinical audit: A simple guide for NHS Boards & partners Authors: Dr. John Bullivant, Director, Good Governance Institute (GGI) Good Governance Andrew Corbett-Nolan, Institute Chair, Institute of Healthcare Management (IHM) Contents Executive summary Executive summary 3 Whilst this guide is specifically about clinical audit, much of what • Delivers a return on investment. is described here is relevant to the way in which NHS Boards can • Improvements are implemented and sustained. 1. Clinical audit: Ten simple rules for NHS Boards 5 monitor clinical quality as a whole within the context of clinical or integrated governance. A PCT has specific responsibilities in relation to clinical audit that 2. Foreword 7 should be managed through the Professional Executive Clinical audit has been endorsed by the Department of Health in Committee (PEC) or an equivalent committee. 3. Clinical audit as part of the modern healthcare system 9 successive strategic documents as a significant way in which the quality of clinical care can be measured and improved. Originally, Boards should use clinical audit to confirm that current practice 4. Definitions and types of clinical quality review 11 clinical audit was developed as a process by which clinicians compares favourably with evidence of good practice and to reviewed their own practice. However, clinical audit is now 5. The importance and relationship of clinical audit to clinical ensure that where this is not the case that changes are made recognised as an effective mechanism for improving the quality that improve the delivery of care. governance, NHS Boards and their partner organisations 15 of care patients receive as a whole. -

Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening

. Cultivating Accountability for health systems strengthening Series of Guides for Enhanced Governance of the Health Sector and Health Institutions in Low- and Middle-Income Countries JUNE 2014 Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements . 4 Introduction . 5 Purpose and Audience for the Guides . 6 Governing Practice—Cultivating Accountability . 8 Your Personal Accountability . 10 Accountability of Your Organization to its Stakeholders . 11 Internal Accountability in Your Organization . 12 Accountability of Health Providers and Health Workers . 13 Managing Performance . 14 Sharing Information . 15 Developing Social Accountability . 17 Using Technology to Support Accountability . 20 Smart Oversight . 21 Appendix: Transparency and Accountability Tools . .. 22 Accreditation . 22 Community Scorecard . 22 Citizen Report Cards . 23 Participatory Budgeting . 23 Independent Budget Analysis . 24 Public Expenditure Tracking Survey . 24 Social Audit .. 24 Citizen’s Charter . 24 Public Hearings . 24 E-Governance . 25 Community Radio . 25 Community-Based Monitoring of Primary Healthcare Providers in Uganda . 26 References and Resources . 27 Transparency . 27 Accountability . 27 Want To Learn More? . 28 Funding was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-11-00015. The contents are the responsibility of the Leadership, Management, and Governance Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 4 Cultivating Accountability for Health Systems Strengthening Acknowledgements This work was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the Leadership, Management, and Governance (LMG) Project . The LMG Project team thanks the staff of the USAID Office of Population and Reproductive Health, in particular, the LMG Project Agreement Officer’s Representative and her team for their constant encouragement and support . -

Report on the Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory

THE ECONOMICS OF PATIENT SAFETY IN PRIMARY AND AMBULATORY CARE Flying blind The Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory Care Flying blind 1 │ This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. The Economics of Patient Safety in Primary and Ambulatory Care © OECD 2018 2 │ Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 3 Key messages .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. This report makes the economic case for safety in the primary and ambulatory care sector ........ 8 1.2. Safety -

The Quality of GP Diagnosis and Referral Catherine Foot Chris Naylor Candace Imison

Research paper The quality of GP diagnosis Authors Catherine Foot and referral Chris Naylor Candace Imison An Inquiry into the Quality of General Practice in England The quality of GP diagnosis and referral Catherine Foot Chris Naylor Candace Imison This paper was commissioned by The King’s Fund to inform the Inquiry panel. The views expressed are those of the authors and not of the panel. Contents Executive summary 3 1 Introduction 7 Context 7 Methods 9 2 The quality of diagnosis in general practice in England 11 What is the role of general practice in diagnosis? 11 High-quality diagnosis in general practice – what does it look like? 13 The current quality of diagnosis in general practice 15 Approaches towards quality improvement 22 Key messages 25 3 The quality of referral in general practice in England 27 What is a GP referral? 27 High-quality referral – what does it look like? 27 The quality of current GP referral practices 32 Approaches towards quality improvement in referral 45 Key messages 48 4 Discussion and conclusions 50 Key findings 50 Recommendations for approaches to improvement 51 Potential quality measures 52 Conclusion 54 Appendices Appendix A: Effective interventions 55 Appendix B: Case study 57 Appendix C: Search terms used in literature review 62 References 63 2 The King’s Fund 2010 Executive summary This report forms part of the wider inquiry into the quality of general practice in England commissioned by The King’s Fund, and focuses specifically on the quality of diagnosis and referral. The report: ■ describes what ‘good’ looks like for diagnosis and referral within primary care ■ describes what is known about the current quality of referral and diagnosis in general practice ■ identifies evidence-based means of improving the quality of GP diagnosis and referral ■ considers the potential for quality measures of diagnosis and referral within primary care. -

Audit Example

West of Scotland Region Greater Glasgow Primary Care Trust Ideas for Audit A practical guide to audit and significant event analysis for general practitioners Paul Bowie Dr Alison Garvie Dr John McKay Associate Advisers NHS Education for Scotland Telephone: 0141 223 1463 E-mail: [email protected] Additional material and advice provided by: Drs Linsey Semple, Janice Oliver & Douglas Murphy [PILOT EDITION – NOVEMBER 2004] 1 CONTENTS Introduction Section ONE AUDIT METHOD The Audit Cycle Choosing an Audit Topic Undertaking and Reporting an Audit Project Methods of Data Collection Peer Assessment of Completed Audit Projects Sampling Section TWO SUGGESTED AUDIT TOPICS Core Chronic Disease Audits Workload & Administration Audits Miscellaneous Audits Section THREE SIGNIFICANT EVENT ANALYSIS The SEA Technique Writing a Significant Event Analysis Report SEA Case Studies Peer Assessment of SEA SEA Proforma APPENDICES Marking Schedule (Audit) Assessment Schedule (SEA) Published Sampling Paper & Chart 2 Introduction This booklet was produced in response to the many requests from health care practitioners and staff for a list of ideas for audit that can be easily applied in general practice. An extensive range of clinical and workload topics is covered and over 100 potential audits are described. A practical guide to basic audit method and the significant event analysis technique is also included. Additional guidance is provided on how to compile simple written reports on the completion of each activity. The language surrounding both approaches to quality improvement can be unnecessarily confusing and potentially off-putting. Hopefully we can shed some light by explaining the various terms used in a straightforward way whilst illustrating this with practical every day examples. -

Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit

Principles for Best Practice in Clinical Audit Radcliffe Medical Press Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd 18 Marcham Road Abingdon Oxon OX14 1AA United Kingdom www.radcliffe-oxford.com The Radcliffe Medical Press electronic catalogue and online ordering facility. Direct sales to anywhere in the world. # 2002 National Institute for Clinical Excellence All rights reserved.This material may be freely reproduced for educational and not for profit purposes within the NHS.No reproduction by or for commercial organisations is permitted without the express written permission of NICE. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 85775 976 1 Typeset by Aarontype Ltd, Easton, Bristol Printed and bound by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall Contents Contributing authors iv Acknowledgements v Foreword vi Clinical audit in the NHS: a statement from the National viii Institute for Clinical Excellence Introduction: using the method, creating the environment 1 Stage One: preparing for audit 9 Stage Two: selecting criteria 21 Stage Three: measuring level of performance 33 Stage Four: making improvements 47 Stage Five: sustaining improvement 59 Appendix I: glossary 69 Appendix II: online resources for clinical audit 73 Appendix III: national audit projects sponsored by the 93 National Institute for Clinical Excellence Appendix IV: further reading 97 Appendix V: key points and key notes 101 Appendix VI: checklists 105 Appendix VII: approach to examining clinical audit during a clinical -

National Evaluation of the Department of Health's Integrated Care Pilots

National Evaluation of the Department of Health’s Integrated Care Pilots Appendices RAND Europe, Ernst & Young LLP Prepared for the Department of Health March 2012 List of Appendices Appendix A: Study protocol Appendix B: Quantitative methods Appendix C: Patient-service user questionnaire Appendix D: Staff questionnaire Appendix E: Template for collecting data from sites Appendix F: Summary of local metrics Appendix G: Site overviews Appendix H: Detailed results of patient and staff survey Appendix I: Costs reported by sites Integrated Care Pilots evaluation: final report Appendix A: Study protocol 1 International Journal of Integrated Care – ISSN 1568-4156 Volume 10, 27 September 2010 URL:http://www.ijic.org URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100969 Publisher: Igitur, Utrecht Publishing & Archiving Services Copyright: Research and Theory Evaluation of UK Integrated Care Pilots: research protocol Tom Ling, Director, Evaluation and Audit, RAND Europe, Westbrook Centre, Westbrook Centre, Milton Road, Cambridge CB4 1YG, UK Martin Bardsley, Head of Research, Nuffield Trust, 59 New Cavendish Street, London W1G 7LP, UK John Adams, Senior Statistician, RAND Health, 1776 Main Street, Santa Monica, CA 90401-3208, USA Richard Lewis, Partner, Ernst and Young LLP, 1 More London Place, London SE1 2AF, UK Martin Roland, Professor of Health Services Research, Institute of Public Health, Forvie Site, Robinson Way, Cambridge CB2 0SR, UK Correspondence to: Martin Roland, Professor of Health Services Research, Institute of Public Health, Forvie Site, Robinson Way, Cambridge CB2 0SR, UK, Phone: +44 1223 330329, Fax: +44 1223 762515, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Background: In response to concerns that the needs of the aging population for well-integrated care were increasing, the English National Health Service (NHS) appointed 16 Integrated Care Pilots following a national competition. -

Significant Event Audit at Rainbows Children's Hospice

Signi cant Event Audit at Rainbows Children’s Hospice - a new way to review incidents Anne-Marie Murkett, Lead Nurse and Tracy Ruthven, Director, Clinical Audit Support Centre What are the benefits of SEA? Types of incidents Rainbows review Rainbows constantly evaluate the SEA What is Signi cant Event Audit (SEA)? process in the organisation, a selection of Near miss incidents the feedback is provided: A process in which individual episodes (when there Medication incidents “We all got the opportunity to have a group has been a signifi cant occurrence either benefi cial Deprivation of Liberty issues meeting to be able to put all points across” or deleterious) are analysed in a systematic way to Tissue viability issues ascertain what can be learnt about the overall quality Managing challenging situations (Staff) of care, and to indicate changes that might lead to Compassionate extubation and MDT working “Well organised and respectful meeting” future improvements (Professor Mike Pringle, 1997) Celebrating best care in exceptional circumstances (External provider) Whistle blowing “To hear both sides of the argument and the SEA process is a good way to review incidents” (Parent) Signi cant Event Audit at Rainbows Children’s Hospice – a case study Step 1 Awareness and prioritisation of a signi cant event Young person was admitted for end of life care. A syringe Step 2 Step 7 driver was inserted to manage her pain. Her pain was up and Information gathering Report, share and review down as noted by her pain score in the days leading up to her death. In order to manage her pain advised to give regular This stage took place as soon as possible after the Rainbows share learning from their incidents across the breakthrough doses of Midazolam and Diamorphine. -

Making Clinical Governance Work for You

Making Clinical Governance Work for You Ruth Chambers Gill Wakley Radcliffe Medical Press Making Clinical Governance Work for You Ruth Chambers and Gill Wakley Forewords by David Haslam and Alison Norman Radcliffe Medical Press ©2000 Ruth Chambers and Gill Wakley Illustrations ©2000 Martin Davies Radcliffe Medical Press Ltd 18 Marcham Road, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 1AA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright owner. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 85775 413 1 Typeset by Advance Typesetting Ltd, Oxfordshire Printed and bound by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall Contents Forewords v Preface vii About the authors ix List of abbreviations x Part One Introduction 1 1 What is clinical governance and how does it fit with professional and service development? 3 2 How to do it: identify your service development needs and your associated learning needs 7 3 Use a range of methods to identify your service development and learning needs 11 4 Where do you want to be and how do you get there? 19 5 Setting priorities for developing clinical governance 23 6 You have identified your learning needs – now what? 27 7 Baseline review 29 Part Two The 14 themes of clinical governance 31 Module 1 Establishing and sustaining a learning culture 33 Module 2 Managing -

Leeds Thesis Template

Using significant event analysis and individual audit and feedback to develop strategies to improve recognition and referral of lung and colorectal cancer at an individual general practice level Daniel Joseph Jones PhD in Medical Sciences The University of Hull and the University of York Hull York Medical School February 2019 - ii - Abstract Introduction: The lifetime risk of developing cancer is 50%. Whilst cancer survival rates are increasing, data suggests UK survival is lower than comparable countries. There is a growing evidence base to suggest cancer survival is linked at least in part, to the early recognition and referral of symptoms in primary care. The role of primary care is vital with 85% of cancers diagnosed following presentation to primary care. Significant event analyses (SEAs) are an effective tool to learn detailed lessons about the primary care interval and SEA research completed so far highlights the importance of safety netting. Method: The research within the thesis was informed by two theories of behaviour change, the Behaviour Change Wheel and Normalisation Process Theory. The methods were split in to three distinct sections. Firstly, a scoping review of safety netting was undertaken. Secondly, the recognition and referral of lung and colorectal cancer symptoms in primary care was investigated using SEAs. Finally, the SEA data generated was used in an audit and feedback intervention to develop a series of action plans. Findings: The definition and content of safety netting was developed. SEAs demonstrated the importance of safety netting in improving the primary care interval, but also highlighted the role of investigations, patient factors and comorbidities. -

Clinical Governance and Continuous Quality Improvement in the Veterinary Profession: a Mixed-Method Study

Clinical governance and continuous Quality Improvement in the veterinary profession: A mixed-method study Tom Ling MA PhD 1 Ashley Doorly 2* Chris Gush BSc MSc2 Lucy Hocking BSc MSc1 1 RAND Europe, Westbrook Centre/Milton Rd, Cambridge, CB4 1YG 2 RCVS Knowledge, Belgravia House, 62–64 Horseferry Road, London, SW1P 2AF * Corresponding Author ([email protected]) ISSN: 2396-9776 Published: 12 May 2021 in: The Veterinary Evidence journal Vol 6, Issue 2 DOI: 10.18849/VE.V6I2.383 Reviewed by: Jo Ireland (BVMS Cert AVP(EM) MRCVS PhD) and Tim Mair (BVSc PhD DEIM DESTS DipECEIM AssocECVDI MRCVS) ABSTRACT 96% of the veterinary profession agrees that Quality Improvement (QI) improves veterinary care. While clinical governance is an RCVS professional requirement, over the last year only 60% spent up to 3 days on the Quality Improvement activities which allow clinical governance to take place. 11% spent no time on it at all. A lack of time, know-how and organisational support were among the barriers preventing its adoption in practice. Rather than being an individual reaction to a problem, Quality Improvement is a formal approach to embedding a set of recognised practices, including clinical audit, significant event audit, guidelines and protocols, benchmarking and checklists. This framework should be applied within a just culture where errors are redefined as learning opportunities, and precedence is given to communication, team-work and team- morale, patient safety, and distributed leadership. Addressing this gap will require evolution – rather than a revolution. Persistent packages, given enough time and addressing the whole flow of the patient journey, trump one-off ‘heroic’ and narrowly-focused interventions.