The Network Analysis of Co ‑Voting Strategies of the KDU ‑ČSL Deputies 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus& 101 Introduction to Business Readings and Workbook Course Designer: Leslie Lum Academic Year 2010-2011 Funded by the Ga

Bus& 101 Introduction to Business Readings and Workbook Course Designer: Leslie Lum Academic Year 2010-2011 Revised 5/11 Funded by the Gates Foundation/State Board Open Course Initiative 5/28/2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Thirty Second Commercial 22 Resume 6 COMPANY ANALYSIS 24 DOING THE COMPANY ANALYSIS 25 Writing Self Assessment (Courtesy Robin Jeffers) 42 Company Selection 26 Company Research 29 Company Analysis- Marketing 37 Company Financial Analysis 38 Company Management Paper 39 Company Presentation 41 Links to sample student paper 42 Team Writing Assignment 47 Team Research Scavenger Assignment 49 MODULE 1: THE CONTEXT OF BUSINESS 51 Module 1 Goals 51 The Economy 52 GDP: One of the Great Inventions of the 20th Century 52 Economic Growth 55 World’s Economies 56 GDP per capita 66 Inflation 69 Business Cycles 74 Government and Policy 77 Fiscal Policy 77 Monetary Policy 79 Currency Risk 80 Economic Indicators 81 Individual Assignment – Calculating growth rates 85 Team Assignment - Economic Indicators 86 Team Assignment – Costco Case 91 Commanding Heights A Case Study of Bubbles 147 Module 1 Questions for Timed Writes 148 2 MODULE 2 - ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND LEGAL FORMS OF BUSINESS 149 Businesses and Entrepreneurship 150 Forms of Ownership 155 Choosing the Business Structure 158 Starting a Business – The Business Plan 159 Breakeven Analysis 167 Team Assignment – Forms of Business 171 Team Assignment – Entrepreneurship and Business Plan 173 Team Assignment Optional - Breakeven analysis of your business plan 174 Module 2 Questions -

November 2020

EPP Party Barometer November 2020 The Situation of the European People’s Party in the EU (as of: 23 November 2020) Dr Olaf Wientzek (Graphic template: Janine www.kas.de Höhle, HA Kommunikation, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung) Summary & latest developments (I) • In national polls, the EPP family are the strongest political family in 12 countries (including Fidesz); the Socialist political family in 6, the Liberals/Renew in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the Eurosceptic/national conservative ECR in 1. Added together, independent parties lead in Latvia. No polls/elections have taken place in France since the EP elections. • The picture is similar if we look at the strongest single party and not the largest party family: then the EPP is ahead in 12 countries (if you include the suspended Fidesz), the Socialists in 7, the Liberals in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the ECR in one land. • 10 (9 without Orbán) of the 27 Heads of State and Government in the European Council currently belong to the EPP family, 7 to the Liberals/Renew, 6 to the Social Democrats / Socialists, 1 to the Eurosceptic conservatives, and 2 are formally independent. The party of the Slovak head of government belongs to the EPP group but not (yet) to the EPP party; if you include him in the EPP family, there would be 11 (without Orbán 10). • In many countries, the lead is extremely narrow, or, depending on the polls, another party family is ahead (including Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Belgium, Poland). Summary & latest developments (II) • In Romania, the PNL (EPP) has a good starting position for the elections (Dec. -

Remembering Sudetenland: on the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing Timothy W

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2006 Remembering Sudetenland: On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing Timothy W. Waters Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Waters, Timothy W., "Remembering Sudetenland: On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing" (2006). Articles by Maurer Faculty. Paper 324. http://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/324 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Remembering Sudetenland: On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing TIMOTHY WILLIAM WATERS* I. To Begin: Something Uninteresting, and Something New ......... 64 II. A im s of the A rticle ................................................................. 66 1II. An Attempt at an Uncontroversial Historical Primer .............. 69 A. Czechoslovakia and Munich .......................................... 69 B. The Bene§ D ecrees ........................................................ 70 C. The Expulsions or Transfers .......................................... 73 D. The Potsdam Agreement .............................................. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Download Article

5 Comment & Analysis CE JISS 2008 Czech Presidential Elections: A Commentary Petr Just Again after fi ve years, the attention of the Czech public and politicians was focused on the Presidential elections, one of the most important milestones of 2008 in terms of Czech political developments. The outcome of the last elections in 2003 was a little surprising as the candidate of the Civic Democratic Party (ODS), Václav Klaus, represented the opposition party without the necessary majority in both houses of Parliament. Instead, the ruling coalition of the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), the Christian-Democratic Union – Czecho- slovak Peoples Party (KDU-ČSL), and the Union of Freedom – Democratic Union (US-DEU), accompanied by some independent and small party Senators was able – just mathematically – to elect its own candidate. However, a split in the major coalition party ČSSD, and support given to Klaus by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM), brought the Honorary Chairman of the ODS, Václav Klaus, to the Presidential offi ce. In February 2007, on the day of the forth anniversary of his fi rst elec- tion, Klaus announced that he would seek reelection in 2008. His party, the ODS, later formally approved his nomination and fi led his candidacy later in 2007. Klaus succeeded in his reelection attempt, but the way to defending the Presidency was long and complicated. In 2003 members of both houses of Parliament, who – according to the Constitution of the Czech Republic – elect the President at the Joint Session, had to meet three times before they elected the President, and each attempt took three rounds. -

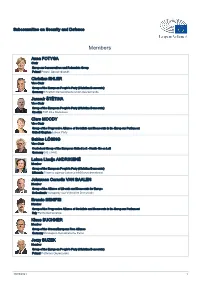

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

The Monkey Cage "Democracy Is the Art of Running the Circus from the Monkey Cage." -- H.L

11/5/13 The Czech paradox: Did the winner lose and the losers win? Sign In SUBSCRIBE: Home Delivery Digital Real Estate Rentals Cars Today's Paper Going Out Guide Find&Save Service Alley PostT V Politics Opinions Local Sports National World Business Tech Lifestyle Entertainment Jobs More The Monkey Cage "Democracy is the art of running the circus from the monkey cage." -- H.L. Mencken What's The Monkey Cage? Archives Follow : The Monkey Cage The Czech paradox: Did the winner lose and the losers win? BY TIM HAUGHTON, TEREZA NOVOTNA AND KEVIN DEEGAN-KRAUSE October 30 at 5:45 am More 3 Comments Also on The Monkey Cage Is the nonproliferation agenda stuck in the Cold War? Make-up artists prepare the Czech Social Democrat (CSSD) chairman Bohuslav Sobotka for his TV appearance after early parliamentary elections finished, in Prague, on Saturday, Oct. 26, 2013. (CTK, Michal Kamaryt/ Associated Press) [Joshua Tucker: Continuing our series of Election Reports, we are pleased to welcome the following post-election report on the Oct. 25-26 Czech parliamentary elections from political scientists Tim Haughton (University of Birmingham, UK), Tereza Novotna (Universite Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium) and Kevin Deegan-Krause, (Wayne State University), who blogs about East European politics at the excellent Pozorblog. Deegan-Krause's pre-election report is available here.] ***** Czech party politics used to be boring. The 2013 parliamentary election, however, highlights the transformation of the party system, the arrival of new entrants and the woes faced by the long-established parties. The Czech Social Democratic Party (CSSD) won the election, but the margin of victory was slender. -

Petr Nečas Zum Premierminister Ernannt

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. TSCHECHIEN DR. HUBERT GEHRING TOMISLAV DELINIC Mitte-Rechts-Koalition steht - MAREN HACHMEISTER Petr Nečas zum Premierminister 30. Juni 2010 ernannt www.kas.de MITTE-RECHTS-PARTEIEN EINIGEN SICH www.kas.de/tschechien Vorbereitung des Staatshaushaltes be- nächsten Jahr auf Steuermehreinnahmen schleunigt Verhandlungen von weiteren 30 Mrd. CZK (1,2 Mrd. €). Die Europäische Kommission bezeichnet Die Koalitionsverhandlungen der drei Mit- die tschechischen Sparmaßnahmen der te-Rechts-Parteien ODS, TOP 09 und VV Regierung Fischer unterdessen schon als wurden nach den tschechischen Parla- „ausreichend“, um die Haushaltsziele mentswahlen Ende Mai mit Hochdruck 2010 zu erreichen. Die Neuverschuldung vorangetrieben. Staatspräsident Václav wird voraussichtlich mit 5,7% des BIP Klaus ernannte Petr Nečas am 28. Juni noch über den 3% der EU- zum Premierminister. Am 29 Juni wurde Konvergenzkriterien liegen. schließlich auch die Regierung zusam- mengestellt. Dem Premierminister und Zunächst überschattete die Wahl des Par- ODS-Vorsitzenden Nečas gelang es so- lamentsvorsitzenden die neue Dreieinig- mit, die Koalitionsverhandlungen noch keit der Mitte-Rechts-Koalition – dem vor Beginn der Haushaltsverhandlungen Gewohnheitsrecht folgend beanspruchte am 07. Juli erfolgreich zu einem Ende zu nämlich die nach den Wahlen stimmen- bringen. stärkste Partei, die Sozialdemokraten (ČSSD), diesen Posten für sich. Sie konn- Koalitionsvereinbarung mit härtestem ten mit ihrem Kandidaten Lubomír Zaorá- Sparpaket der tschechischen Geschich- lek schließlich nur den stellvertretenden te Parlamentsvorsitz ergattern, da die künf- tige Koalition Miroslava Němcová (ODS) Die Koalitionsvereinbarung der Mitte- durchsetzte. Rechts-Koalition enthält sieben Kapitel. Nach den anfänglichen Forderungen der Auch die Frage der Ministerienverteilung Partei VV zur Kürzung des Verteidigungs- brachte harte Verhandlungen mit sich. -

Far from Stability: the Post-Election Landscape in Bulgaria Dariusz Kałan

No. 50 (503), 15 May 2013 © PISM Editors: Marcin Zaborowski (Editor-in-Chief) . Katarzyna Staniewska (Managing Editor) Jarosław Ćwiek-Karpowicz . Artur Gradziuk . Piotr Kościński Roderick Parkes . Marcin Terlikowski . Beata Wojna Far from Stability: The Post-Election Landscape in Bulgaria Dariusz Kałan Early parliamentary elections not only will not help restore political stability in Bulgaria but also could further deepen the chaos because of the high dispersion of votes and the expected difficulties with creating a coalition. For a country immersed in crisis, maintaining the post-election stalemate is particularly not beneficial because of the deteriorating economic situation and growing public pressure. Regardless of which party will return to power, one should not expect a significant improvement in Bulgaria’s image in the EU or a positive settlement of the most important issues, including the country’s rapid accession to the Schengen area. Although the winner of the early parliamentary elections of 12 May was the centre-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB, 30% of votes), for all four parties that exceeded the 4% electoral threshold, the results can be seen as satisfactory. GERB, the ruling party in 2009–2013, won for the second time in a row during unfavourable economic and social situations. The similar support for the Bulgarian Socialist Party (27%), which received more than 600,000 additional votes than in 2009, is because of the mobilisation of its permanent electorate and generational changes in the party. Also, for the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (11%), which represents the Turkish minority, and the nationalist Attack party (7%), the results are a confirmation of their stable positions on the political scene. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Political Conflict, Social Inequality and Electoral Cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-2018

World Inequality Lab – Working Paper N° 2020/25 Political conflict, social inequality and electoral cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-2018 Attila Lindner Filip Novokmet Thomas Piketty Tomasz Zawisza November 2020 Political conflict, social inequality and electoral cleavages in Central-Eastern Europe, 1990-20181 Attila Lindner, Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, Tomasz Zawisza Abstract This paper analyses the electoral cleavages in three Central European countries countries—the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland—since the fall of communism until today. In all three countries, the left has seen a prolonged decline in support. On the other hand, the “populist” parties increased their support and recently attained power in each country. We relate this to specific trajectories of post-communist transition. Former communist parties in Hungary and Poland transformed themselves into social- democratic parties. These parties' pro-market policies prevented them from establishing themselves predominantly among a lower-income electorate. Meanwhile, the liberal right in the Czech Republic and Poland became representative of both high-income and high-educated voters. This has opened up space for populist parties and influenced their character, assuming more ‘nativist’ outlook in Poland and Hungary and more ‘centrist’ in the Czech Republic. 1 We are grateful to Anna Becker for the outstanding research assistance, to Gábor Tóka for his help with obtaining survey data on Hungary and to Lukáš Linek for helping with obtaining the data of the 2017 Czech elections. We would also like to thank Ferenc Szűcs who provided invaluable insights. 1 1. Introduction The legacy of the communist regime and the rapid transition from a central planning economy to a market-based economy had a profound impact on the access to economic opportunities, challenged social identities and shaped party politics in all Central European countries. -

Czech Debate on the EU Membership Perspectives of Turkey and Ukraine

Czech debate on the EU membership perspectives of Turkey and Ukraine David Král EUROPEUM Institute for European Policy November 2005 Acknowledgement: This report was written as part of an international project, mapping the state of debate on the EU membership perspectives of Turkey and Ukraine in four Central European countries: Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary and Slovenia and undertaken jointly by EUROPEUM, Institute of Public Affairs (Warsaw), Centre for Policy Studies at CEU (Budapest) and Peace Institute (Ljubljana). Introduction The question of further EU enlargement is an issue that remained very much on the table even after the May 2004 “Big Bang” expansion of the Union. While in the ten countries that recently acceded all the efforts thus far have been focusing on the rules and conditions of entering the exclusive club, not much space in the public debate remained for discussing the issue as to what are the further steps in EU enlargement, which countries should be considered for joining and what are the stakes of the new member states, including the Czech Republic, in the whole process. This paper will look into examining the Czech attitudes towards the EU membership perspectives of two countries: Turkey and Ukraine. It will deal with the attitudes of the political representation, including the political parties, government and diplomatic service (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and other governmental stakeholders. Further, it will try to give an account of how the issue was treated in the media, especially in the major opinion shaping newspapers. Thirdly, it will try to assess what are the other stakeholders in the process, especially within the ranks of the civil society and how they are likely to shape the public debate.