Panchayat Irrigation Management: a Case Study of Institutional Reforms Programme Over Teesta Command in West Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri District Disaster Management Authority Jalpaiguri O/o the District Magistrate, Jalpaiguri West Bengal Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Aim and Objectives of the District Disaster Management Plan............................................ 1 1.2 Authority for the DDMP: DM Act 2005 ............................................................................... 2 1.3 Evolution of the DDMP ........................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibility .................................................................................... 4 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework ............................................................................................. 5 1.6 Approval Mechanism of the Plan: Authority for implementation (State Level/ District Level orders) ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.7 Plan Review & Updation: Periodicity ................................................................................... 6 2 Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk Assessment ............................................................... 7 2.1 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Assessment ......................................................................... 7 2.2 Matrix of Seasonality of Hazard .......................................................................................... -

The Most Lasting Impact of the Imperial Rule in the Jalpaiguri District

164 CHAPTER 111 THE BRITISH COLONIAL AUTHORITY AND ITS PENETRATION IN THE CAPITAL MARKET IN THE NORTHERN PART OF BENGAL The most lasting impact of the imperial rule in the Jalpaiguri District especially in the Western Dooars was the commercialisation of agriculture, and this process of commercialisation made an impact not only on the economy of West Bengal but also on society as well. J.A. Milligan during his settlement operations in the Jalpaiguri District in 1906-1916 was not im.pressed about the state of agriculture in the Jalpaiguri region. He ascribed the backward state of agriculture to the primitive mentality of the cultivators and the use of backdated agricultural implements by the cultivators. Despite this allegation he gave a list of cash crops which were grown in the Western Duars. He stated, "In places excellent tobacco is grown, notably in Falakata tehsil and in Patgram; mustard grown a good deal in the Duars; sugarcane in Baikunthapur and Boda to a small extent very little in the Duars". J.F. Grunning explained the reason behind the cultivation of varieties of crops in the region due to variation in rainfall in the Jalpaiguri district. He said "The annual rainfall varies greatly in different parts of the district ranging from 70 inches in Debiganj in the Boda Pargana to 130 inches at Jalpaiguri in the regulation part of the district, while in the Western Duars, close to the hills, it exceeds 200 inches per annum. In these circumstances it is not possible to treat the district as a whole and give one account of agriculture which will apply to all parts of it".^ Due to changes in the global market regarding consumer commodity structure suitable commercialisation at crops appeared to be profitable to colonial economy than continuation of traditional agricultural activities. -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

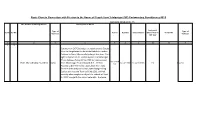

Route Chart in Connection with Election to the House of People from 3-Jalpaiguri (SC) Parlamentary Constituency-2019

Route Chart in Connection with Election to the House of People from 3-Jalpaiguri (SC) Parlamentary Constituency-2019 DISTANCE FROM DC/RC. TO No. & Name of Polling Station Description of Route Last point Type of Type of Sl. No AC No. Pucca Kuchha Total distance where Vehicle Sector No Vehicies Vehicies will stay 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 5 1 19 Starting from DCRC,Jalpaiguri proceed towards Gosala More to Rangdhamali to Balakoba Battale to Ambari Falakata to Gorar More via Sahudanghi Hut then . Turn right and proceeds to Eastern Bypass to Bhaktinagar P.S via Salugara Range Office, SMC dumping ground. 60x 2=120 19/01 Bhanu Bhakta Pry School Sumo From Bhaktinagar PS (Checkpost) N.H. -31 then 05 x 2=10Km 65 x 2=130 Km PS 1 Sumo Km Proceed to 8th Mile forest range office. Turn right forest Kuchha and proceed to Chamakdangi Polling Station and drop the Team at PS No 19/1 and Halt. next day after completion of poll the vehical will back to DCRC alongwith the same route with the team . Starting from DCRC,Jalpaiguri proceed towards Gosala More to Rangdhamali to Balakoba Battale to Ambari Falakata to Gorar More via Sahudanghi Hut then. Turn right and proceeds to Eastern Bypass to Bhaktinagar P.S via Salugara Range Office, SMC dumping ground. 19/02, 03, 04, 05 From Bhaktinagar PS (Checkpost) N.H. -31 and turn 52 x 2=104 2 19 Salugara High School Maxi taxi right then Proceed upto S.B.I. Salugara Branch near 0 52 x 2=104 Km PS Maxi taxi Km (1st, 2nd & 3rd, 4th Room) Salugara Bajar then turn Right and Proceed on Devi Choudharani road up to I.O.C. -

DDRC Jalpaiguri10092018

5 4 3 2 1 SL.NO MIYA MIYA AKBAR ALI DHRUBA DHRUBA DUTTA PAYAL KHATUN PAYAL ANIMA ANIMA ROY PAYAL ROY PAYAL Name of beneficiary CAMP NAME : DDRC JALPAIGURI DATE : 10.09.2018 : DATE JALPAIGURI DDRC : NAME CAMP ROY,BARAKAMAT,JALPAIGUR TOLL,JAIGAON,JALPQAIGURI- PARA,BARUBARI,BERUBARI,J ROY,BAHADUR,JALPAIGURI- C/O C/O SAPIKUL ALAM,PURBA PARA,JALPAIGURI-735102 JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI NAGAR,MOHANTA NAGAR,MOHANTA ALPAIGURI-735137 C/O C/O MIYA ABDUL DUTTA,MOHIT DUTTA,MOHIT C/O SHYAMAL C/O SHYAMAL C/O SANTOSH C/O SANTOSH LAL BAJAR C/O C/O BASI I-735305 735121 736182 Complete Address 14 14 48 65 11 Age M M F F F M/F GEN GEN OBC SC SC Caste 3500 3000 3000 3600 3000 Income HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING AID V AID V AID V AID V AID V Type of aid(given) 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 Date on Which (given) 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total Cost of aid,including Fabrication/Fitment charges 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Subsidy provided Travel cost paid to outstation beneficiary Board and lodging expenses paid Whether any surgical correction undertaken 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total of 10+11+12+13 No of days for which stayed Whether accomanied by escort YES YES YES YES YES Photo of beneficiary* 9002033171 9434228632 7076669744 9832340736 9932546247 Mobile No. or lan d line number with STD Code** C/O BABLU ROY,DHUPGURI,UTTAR HEARING 6 SIMA ROY 7 F SC 4000 10.09.2018 5680 100% 5680 YES 8512999121 KATHULIYA,JALPAIGURI- AID V 735210 C/O MADHUSUDAN APARNA CHAKRABORTY,ADARPARA HEARING 7 16 F GEN 2000 10.09.2018 5680 -

FOREST RESOURCE M TS PROBLEMS and PROSPECTS a STUDY of DARJEELING and Lalpaiguri DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL

FOREST RESOURCE M TS PROBLEMS AND PROSPECTS A STUDY OF DARJEELING AND lALPAIGURI DISTRICT, WEST BENGAL A Ph. D.Thesis a Submitted by SWAPAN KUMAR RAKSHIT, M.COM Department of Geography and Applied Geography North Bengal University District : Darjeeling West Bengal, India - 734430 2003 J 6 7 9 3 G I _■ l'iXI PREFACE Every country is blessed with many natural resource that human labour and intellect can exploit for it’s own benefits. Of all natural resource “Forest” is said to be one that is aknost renewable. Being most important renewable resource, the forests, as green gold, are performing a number of fiinctions includiag ecological, recreational and economic. Forests ia the sub-Himalayan North Bengal (Jalpaiguri and Daijeeling district*) are the source of many kiads of timber with varied technical properties, which serve the require ments of the buUding, industry and commimication as weU as an expanding range of indus tries in which wood forms the principal raw material. Forests in the study area are also the source of fire wood. This apart, forests perform a vital function in protecting the soU on sloping lands from accelerated erosion by water. In the catchment areas of rivers of the districts, they sei-ve to moderate floods and maintain stream flow. They influence the local climate and shelter wild life. Forests play a pivotal role m the overall development of the study area. This is, there fore, why forests have been given due attention for the development of this region. Sev eral forestry programme have been drawn by the state government in the area on system atic basis, consistent with the local requirements. -

Wildlife Annual Report 15-16

I N D E X Contents Page No. ŚĂƉƚĞƌϭ͗/ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƟŽŶƚŽƚŚĞ^ƚĂƚĞ ϭ͘Ϭϭ/ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƟŽŶƚŽƚŚĞ^ƚĂƚĞ 1 – 4 ϭ͘ϬϮ&ŽƌĞƐƚĂŶĚWƌŽƚĞĐƚĞĚƌĞĂƐŽĨtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 5 – 6 ŚĂƉƚĞƌϮ͗tŝůĚůŝĨĞŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶŝŶƚŚĞ^ƚĂƚĞ Ϯ͘ϬϭtŝůĚůŝĨĞŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĂŶĚDĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 7 – 11 Ϯ͘ϬϮEĂƟŽŶĂůWĂƌŬΘ^ĂŶĐƚƵĂƌŝĞƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 12 – 14 Ϯ͘ϬϯdŝŐĞƌZĞƐĞƌǀĞƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 14 Ϯ͘ϬϰůĞƉŚĂŶƚZĞƐĞƌǀĞƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 15 Ϯ͘Ϭϱ>ŽĐĂƟŽŶŽĨWƌŽƚĞĐƚĞĚƌĞĂƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 16 Ϯ͘Ϭϲ^ƚĂƚƵƐŽĨDĂŶĂŐĞŵĞŶƚWůĂŶͬdŝŐĞƌŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶWůĂŶ;dWͿƉƌĞƉĂƌĂƟŽŶ 17 ŚĂƉƚĞƌϯ͗džͲ^ŝƚƵŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶƌĞĂƐ ϯ͘ϬϭdžͲ^ŝƚƵŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶŽĨƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚǁŝůĚůŝĨĞƐƉĞĐŝĞƐ 19 – 21 ϯ͘ϬϮŽŽƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 21 – 22 ϯ͘Ϭϯ>ŽĐĂƟŽŶŽĨŽŽƐΘZĞƐĐƵĞĞŶƚƌĞƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 23 ϯ͘ϬϰZĞĐŽŐŶŝƟŽŶ^ƚĂƚƵƐŽĨZĞƐĐƵĞĞŶƚƌĞƐͬĞĞƌWĂƌŬͬŽŽƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 24 – 25 ϯ͘Ϭϱ/ŶƚƌŽĚƵĐƟŽŶƚŽŽŽƐ 25 – 30 ŚĂƉƚĞƌϰ͗ƐƟŵĂƟŽŶŽĨtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐ 31 – 38 ŚĂƉƚĞƌϱ͗,ƵŵĂŶͲtŝůĚůŝĨĞŽŶŇŝĐƚ͖DŝƟŐĂƟŽŶŽĨŽŶŇŝĐƚ ϰ͘Ϭϭ,ƵŵĂŶͲtŝůĚůŝĨĞŽŶŇŝĐƚƌĞĂƐŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 39 – 42 ϰ͘ϬϮ,ƵŵĂŶͲtŝůĚůŝĨĞŽŶŇŝĐƚ 42 – 43 ϰ͘ϬϯĞĂƚŚŽĨtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲŝŶtĞƐƚĞŶŐĂů 44 ϰ͘ϬϰĞĂƚŚŽĨtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐĐĂƵƐĞĚďLJdƌĂŝŶĂĐĐŝĚĞŶƚĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 44 ϰ͘ϬϱĞĂƚŚŽĨtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐĐĂƵƐĞĚďLJZŽĂĚĂĐĐŝĚĞŶƚĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 45 ϰ͘ϬϲĞĂƚŚŽĨĞůĞƉŚĂŶƚƐĐĂƵƐĞĚďLJĞůĞĐƚƌŽĐƵƟŽŶĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 45 – 47 ϰ͘ϬϳĞĂƚŚŽĨĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚĂůůĞƉŚĂŶƚƐĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 47 ϰ͘ϬϴWĞƌƐŽŶŬŝůůĞĚͬŝŶũƵƌĞĚďLJtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 47 – 48 [i] Contents Page No. ϰ͘Ϭϵ&ŽƌĞƐƚ^ƚĂī<ŝůůĞĚͬ/ŶũƵƌĞĚďLJtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 48 ϰ͘ϭϬ^ƚƌĂLJŝŶŐŽĨtŝůĚŶŝŵĂůƐĚƵƌŝŶŐϮϬϭϱͲϭϲ 49 – 56 ϰ͘ϭϭDŝƟŐĂƟŽŶŽĨŽŶŇŝĐƚ 56 – 58 ϰ͘ϭϮ^ƚĞƉƐƚĂŬĞŶƚŽƉƌĞǀĞŶƚĚĞĂƚŚŽĨǁŝůĚĂŶŝŵĂůƐŝŶĐůƵĚŝŶŐĞůĞƉŚĂŶƚĚƵĞƚŽƚƌĂŝŶĂĐĐŝĚĞŶƚ 58 – 62 ϰ͘ϭϯDĞĂƐƵƌĞƐƚĂŬĞŶĨŽƌƉƌŽƚĞĐƟŽŶŽĨŵŝŐƌĂƚŽƌLJĞůĞƉŚĂŶƚƐĂĐƌŽƐƐŝŶƚĞƌͲƐƚĂƚĞďŽƌĚĞƌƐ 63 ϰ͘ϭϰDĞĂƐƵƌĞƐƚĂŬĞŶƚŽƉƌĞǀĞŶƚ,ƵŵĂŶͲdŝŐĞƌĐŽŶŇŝĐƚ -

Paper Download

Culture survival for the indigenous communities with reference to North Bengal, Rajbanshi people and Koch Bihar under the British East India Company rule (1757-1857) Culture survival for the indigenous communities (With Special Reference to the Sub-Himalayan Folk People of North Bengal including the Rajbanshis) Ashok Das Gupta, Anthropology, University of North Bengal, India Short Abstract: This paper will focus on the aspect of culture survival of the local/indigenous/folk/marginalized peoples in this era of global market economy. Long Abstract: Common people are often considered as pre-state primitive groups believing only in self- reliance, autonomy, transnationality, migration and ancient trade routes. They seldom form their ancient urbanism, own civilization and Great Traditions. Or they may remain stable on their simple life with fulfillment of psychobiological needs. They are often considered as serious threat to the state instead and ignored by the mainstream. They also believe on identities, race and ethnicity, aboriginality, city state, nation state, microstate and republican confederacies. They could bear both hidden and open perspectives. They say that they are the aboriginals. States were in compromise with big trade houses to counter these outsiders, isolate them, condemn them, assimilate them and integrate them. Bringing them from pre-state to pro-state is actually a huge task and you have do deal with their production system, social system and mental construct as well. And till then these people love their ethnic identities and are in favour of their cultural survival that provide them a virtual safeguard and never allow them to forget about nature- human-supernature relationship: in one phrase the way of living. -

An Enquirv of Tribal Develo·Pment in the District of Jalpaiguri CHAPTER- IV

Chapter- 4 An enquirv of Tribal Develo·pment in the District of Jalpaiguri CHAPTER- IV An Enquiry of Tribal Development ~n the district of Jalpaiguri The district of J alpaiguri as an administrative unit which came into being on January 1869 by the amalgamation of the Western Duars district with the Ja1paiguri sub-division of Rangpur district '(Notification of December R, 1801~). The .Jalpaiguri sub-division has been formed in 1854 with: headquarters ar Sookanec and was called the Sookanee sub-division. The .· three Police Station Fakirganj (New J alpaiguri), Bacia and Sanyasikata (now Rajganj) comprising the sub-division were transferred to newly formed district of Jalpaiguri. At the commencement of 1869 the T~ana of Patgram was also separated from Rangpur and to Jalpaiguri on April 1870. Jalpaiguri is one of the richest district of West Bengal in respect of natural resources. It enjoys special features in geographical locations, demographic struct·ur-c, wit:h natural abundance of flora and fauna. Jalpaiguri has the boundary with Bangladesh in South, Bhutan in North, Assam in East and Bangladesh and Darjeeling in West. It is the second largest district of West Bengal in respect of Schedule Tribes population. The demographic feature in this clisr-rict has a very distinctive position. Out of the total population of 28,00,543 about SWYc~ belong to SC/ST communities. 10,35,971 persons belong tci SC communities and 5,89,225 persons belong ·to ST communities (.According to 1991 Census). However, 2001 Census report poiq.ted out that out of the total population of 34,011;73 about 52% belong to SC/ST communities. -

Location of Land Use Zones of Three Planning Areas Under Sjda for Guidance

LOCATION OF LAND USE ZONES OF THREE PLANNING AREAS UNDER SJDA FOR GUIDANCE. Broad Land Use Zones of Three Planning Areas:- 1. Siliguri Planning Area. 2. Jalpaiguri Planning Area. 3. Naxalbari Planning Area. Land Location Mouza/Sheet J.L. No. P.S. District Name of the Sub- Land Use uses Proposed use of No. Planning Zone and Planning Planning Proposed use Zone Sub-Planning Area Zone No. Area No. Block No. No. 1. SILIGURI PLANNING AREA Residential, Siliguri M. C. - Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/01/01 Commercial & Ward No. 2 & Sheet No. 2. Residential & Mixed 3. 01/01 Commercial Siliguri M. C. - Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/01/02 Residential Ward No. 2. Sheet No. 1 & 2. Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/02/01 Residential Ward No. 1. Sheet No. 2. Transportation & Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/02/02 Communication, Ward No. 1. Sheet No. 2. Siliguri Transportation and Residential 01 Communication, 01/02 Agricultural, Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling Municipality Residential and 01/02/03 Residential Ward No. 1. Sheet No. 2. Commercial Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/02/04 Residential Ward No. 1. Sheet No. 2. Residential & Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling 01/02/05 Commercial Ward No. 1. Sheet No. 2. Mixed use with Siliguri M. C. Mouza Siliguri 110 (88) Siliguri Darjeeling Industrial, Commercial, Ward No. 4. Sheet No. 3, Commercial, 01/03 01/03/01 Residential, 136, 14. -

15. DETAILS of SECTOR OFFICERS Sector No

15. DETAILS OF SECTOR OFFICERS Sector No. & Name of AC Name Designation Office Address Mobile No. No. 15-Dhupguri (SC) 1 Aniruddha Ghosh Choudhury EA Banarhat-I GP Banarhat-I GP Office , GP-Banarhat, PS-Banarhat 9434503661 15-Dhupguri (SC) 2 Surajit Barman JE (RI) Banarhat T.G. Pry. School, GP-Banarhat, PS-Banarhat 8250494395 15-Dhupguri (SC) 3 Apurba Kumar Dev RI BL&LRO Office, Dhupguri Totapara T.G. Pry. School, GP-Banarhat, PS-Banarhat 9832576798 15-Dhupguri (SC) 4 Saptarshi Maitra IMW Salbari-I GP Office, GP-Salbari-I, PS-Banarhat 7603091439 15-Dhupguri (SC) 5 Rahul Deb Barman SAE, Dhupguri Municipality Paschim Duramari New Primary School, GP-Salbari-I, PS-Banarhat 9733320469 15-Dhupguri (SC) 6 Rajesh Roy EA , Salbari-II GP Salbari-II GP Office, GP-Salbari-II, PS-Banarhat 8670397128 15-Dhupguri (SC) 7 Sukumar Basak SAE , Dhupguri Municipality Baniapara Chowrasta High School, GP-Salbari-II, PS-Banarhat 9832488843 15-Dhupguri (SC) 8 Utsav Lama RI, BL&LRO Dhupguri Jharaltagram-I GP Office, GP-Jharaltagram-I, PS-Dhupguri 7029931175 15-Dhupguri (SC) 9 Kamal Sarkar EA Binnaguri GP Basuardanga MSK, GP-Jharaltagram-I, PS-Dhupguri 9775768618 15-Dhupguri (SC) 10 Tapash Das SI of School Dhupguri Khattimari High School, GP- Jharaltagram-II, PS-Dhupguri 9547591289 15-Dhupguri (SC) 11 Ashis Lepcha AE, PWD Dhupguri Jharaltagram-II GP Office, GP- Jharaltagram-II, PS-Dhupguri 7076516108 15-Dhupguri (SC) 12 Biswajit Roy JE( R) Dhupguri Block Gadhearkuthi GP Office, GP-Gadhearkuthi, PS-Dhupguri 9933726626 15-Dhupguri (SC) 13 Dilip Barman JE(BP) Dhupguri Block, Gadhaerkuthi High School, GP-Gadhearkuthi, PS-Dhupguri 9434242083 15-Dhupguri (SC) 14 Prasenjit Bhattacharjee BL&LRO Dhupguri Pradhan Para S.C. -

List of Roads Maintained by Different Divisions in Alipurduar District

LIST OF ROADS MAINTAINED BY DIFFERENT DIVISIONS IN ALIPURDUAR DISTRICT DIVISION: ALIPURDUAR CONSTRUCTION DIVISION, PWD Sl. Name of the Road No. Length (in km) Category 1 Alipurduar Patlakhowa Road (Sonapur to Alipurduar) SH 17.60 2 Alipurduar Volka Road SH 21.25 3 Buxa Forest Road (0.00 kmp to 16.00 kmp) (Alipurduar to Rajabhatkhawa) SH 16.00 4 Buxa Forest Road (16.00 kmp to 25.50 km) MDR 9.50 5 Buxirhat Jorai Road (10.65 km to 17.80 km) MDR 7.15 6 Cross Road Within Town MDR 8.91 7 Kumargram Jorai Road MDR 25.00 TOTAL 105.41 DIVISION: ALIPURDUAR HIGHWAY DIVISION, P.W (Roads) Dtte. Sl. Name of the Road No. Length (in km) Category 1 Alipurduar Kumargram Road MDR 20.00 2 Buxa to Jayanti Road MDR 5.20 3 Dalgaon Gomtu (Bhutan) Road MDR 10.00 4 Dalgaon Lankapara Road MDR 18.00 5 Dhupguri Falakata Road (15.23 km to 21.70 km) MDR 6.47 6 Ethelbari to Khagenhat Road MDR 10.00 7 Falakata Madarihat Road SH 22.70 8 Ghargharia to Salbari Road VR 4.10 9 Hantapara to Totopara Road VR 7.00 10 Hatipota to Samuktala Road MDR 16.05 11 Jayanti Dhawla Road MDR 15.00 12 Kalchini to Jaygaon Road MDR 9.25 13 Kalchini to Paitkapara Road MDR 17.84 14 Link Road From Falakata P.S to Falakata Petrol Pump MDR 0.80 15 Madarihat to Hantapara Road MDR 7.00 16 Rajabhatkhawa Joygaon Road (upto Old Hasimara) SH 24.50 17 Silbari to Salkumarhat Road MDR 10.85 18 Sinchula Hill Road ODR 5.00 19 Sonapur More of NH-31 to Hasimara on NH-31 via Chilapata Forest MDR 25.40 20 Tapsikhata to Salbari Road MDR 3.60 21 Telipara to Tiamarighat Road MDR 13.84 22 Union Academy to Godamdabri Road(Via Hamiltonganj Bazar) MDR 2.50 TOTAL 255.10 1 LIST OF ROADS MAINTAINED BY DIFFERENT DIVISIONS IN COOCHBEHAR DISTRICT DIVISION: COOCHBEHAR DIVISION, PWD Sl.