The Most Lasting Impact of the Imperial Rule in the Jalpaiguri District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri

District Disaster Management Plan 2020-21 Jalpaiguri District Disaster Management Authority Jalpaiguri O/o the District Magistrate, Jalpaiguri West Bengal Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Aim and Objectives of the District Disaster Management Plan............................................ 1 1.2 Authority for the DDMP: DM Act 2005 ............................................................................... 2 1.3 Evolution of the DDMP ........................................................................................................ 3 1.4 Stakeholders and their responsibility .................................................................................... 4 1.5 How to use DDMP Framework ............................................................................................. 5 1.6 Approval Mechanism of the Plan: Authority for implementation (State Level/ District Level orders) ............................................................................................................................... 5 1.7 Plan Review & Updation: Periodicity ................................................................................... 6 2 Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk Assessment ............................................................... 7 2.1 Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Assessment ......................................................................... 7 2.2 Matrix of Seasonality of Hazard .......................................................................................... -

New Regn.Pdf

LIST OF NEWLY REGISTERED DEALERS FOR THE PERIOD FROM 01-DECEMBER-08 TO 16-DECEMBER-08 CHARGE NAME VAT NO. CST NO. TRADE NAME ADDRESS ALIPUR 19604024078 19604024272 BAHAR COMMODEAL PVT. LTD. 16 BELVEDRE ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604028055 MAHAVIR LOGISTICS 541/B, BLOCK 'N NW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604027085 P. S. ENTERPRISE 100 DIAMOND HARBOUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604031062 19604031256 PULKIT HOLDINGS PVT. LTD. 16F JUDGES COURT ROAD KOLKATA 700027 19604030092 19604030286 R. S. INDUSTRIES (INDIA) 26E, TURF ROAD KALIGHAT 700025 19604026018 19604026212 RAJ LAXMI JEWELLERS 49/1 CIRCULAR GARDEN ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604025048 19604025242 SAPNA HERBALS & COSMETICS PVT. LTD. 12/5 MOMINPUR ROAD KOLKATA 700023 19604029025 19604029219 SOOKERATING TEA ESTATE PVT. LTD. P-115, BLOCK-F NEW ALIPORE KOLKATA 700053 19604023011 SURFRAJ & CO. F-79 GARDENREACH ROAD KOLKATA 700024 ARMENIAN STREET 19521285018 19521285212 M/S. TEXPERTS INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED, 21, ROOPCHAND ROY STREET, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700007 19521286085 19521286279 TIRUPATI ENTERPRISES IST FLOOR, 153, RABINDRA SARANI, KOLKATA 700007 ASANSOL 19747189094 ARCHANA PEARLS 8, ELITE PLAZA G.C. MITRA ROAD ASANSOL 713301 19747194041 ASANSOL REFRIGERATOR MART 46 G.T. ROAD, DURGA MARKET, GIRIJA MOR ASANSOL 713301 19747182013 AUTO GARAGE FARI ROAD BARAKAR, ASANSOL 713324 19747178036 BADAL RUIDAS VIA- ASANSOL KALLA VILLAGE, RUIDAS PAR KALLA (C.H) 713340 19747175029 19747175223 BALBIR ENTERPRISES STATION ROAD BARAKAR 713324 19747179006 19747179297 BAZAR 24 24 G.T. ROAD (WEST) RANIGANJ SEARSOL RAJBARI 713358 -

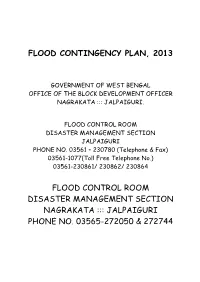

Disaster Management Plan of Nagrakata Block

FLOOD CONTINGENCY PLAN, 2013 GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL OFFICE OF THE BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03561 – 230780 (Telephone & Fax) 03561-1077(Toll Free Telephone No.) 03561-230861/ 230862/ 230864 FLOOD CONTROL ROOM DISASTER MANAGEMENT SECTION NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI PHONE NO. 03565-272050 & 272744 Introduction Block administration in general, and all three tier P.R. bodies in particular are giving the best of their activities to all round development of human habitats including living and material properties. As a part of developmental administrative wing, effort with a view to achieving target of materializing a really developed state of affairs in every sphere of our lives, are always exerted & ideas put forth by all concerned. However, much of our sincere endeavors in this direction are so often battered & hamstrung by sudden visit of ominous calamities and evil disasters. Thus, to combat such ruthless spells & minimize risk hazards and loss of resources, surroundings, our achievements, concrete preparation on Disaster Management is an inevitable part of our curriculum. Such preparedness of ours undoubtedly involves all departments, sectors concerned. Hence, we prepare a realistic Flood Contingency Plan to combat the ruthless damage caused to our flourishing habitats. Accordingly, this time for 2013, an elaborate plan has been worked out with every aspiration to successfully rise above the situation pursuing a planned step forward. BLOCK DEVELOPMENT OFFICER NAGRAKATA ::: JALPAIGURI. CONTACT TELEPHONE NUMBERS FOR NAGRAKATA DEVELOPMENT BLOCK. SL. Name of the Office Telephone No. NO. 01. B.D.O, Nagrakata 03565-272050 Savapati, 02. Nagrakata Panchayat 03565-272309 Samity 03. -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

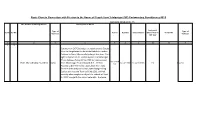

Route Chart in Connection with Election to the House of People from 3-Jalpaiguri (SC) Parlamentary Constituency-2019

Route Chart in Connection with Election to the House of People from 3-Jalpaiguri (SC) Parlamentary Constituency-2019 DISTANCE FROM DC/RC. TO No. & Name of Polling Station Description of Route Last point Type of Type of Sl. No AC No. Pucca Kuchha Total distance where Vehicle Sector No Vehicies Vehicies will stay 1 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 5 1 19 Starting from DCRC,Jalpaiguri proceed towards Gosala More to Rangdhamali to Balakoba Battale to Ambari Falakata to Gorar More via Sahudanghi Hut then . Turn right and proceeds to Eastern Bypass to Bhaktinagar P.S via Salugara Range Office, SMC dumping ground. 60x 2=120 19/01 Bhanu Bhakta Pry School Sumo From Bhaktinagar PS (Checkpost) N.H. -31 then 05 x 2=10Km 65 x 2=130 Km PS 1 Sumo Km Proceed to 8th Mile forest range office. Turn right forest Kuchha and proceed to Chamakdangi Polling Station and drop the Team at PS No 19/1 and Halt. next day after completion of poll the vehical will back to DCRC alongwith the same route with the team . Starting from DCRC,Jalpaiguri proceed towards Gosala More to Rangdhamali to Balakoba Battale to Ambari Falakata to Gorar More via Sahudanghi Hut then. Turn right and proceeds to Eastern Bypass to Bhaktinagar P.S via Salugara Range Office, SMC dumping ground. 19/02, 03, 04, 05 From Bhaktinagar PS (Checkpost) N.H. -31 and turn 52 x 2=104 2 19 Salugara High School Maxi taxi right then Proceed upto S.B.I. Salugara Branch near 0 52 x 2=104 Km PS Maxi taxi Km (1st, 2nd & 3rd, 4th Room) Salugara Bajar then turn Right and Proceed on Devi Choudharani road up to I.O.C. -

An Empirical Study of Cooch Behar District, West Bengal, India Dulon Sarkar

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1719 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2863 (Online) Vol 2, No.9, 2012 Status of Rural Women, Left Behind for Male Labour Circulation: an Empirical Study of Cooch Behar District, West Bengal, India Dulon Sarkar Research Scholar (UGC NET), Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, Santineketan, West Bengal, India, *Email of corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Circulation, being a typical component of migration creates dynamic and complex social process through the constant interaction with economic, demographic, social and political elements of a particular society in a space time lattice. The term ‘circulation’ refers to temporary cyclical movement of a person or a group of person with no declared intention of permanent change of residence. It always ends in the place of origin. The study area, Cooch Behar district of West Bengal, India ranked 11 out of 19 districts (HDR, 2004) of West Bengal proves its incredible backwardness in every aspect. Inadequate employment opportunity due to industrial backwardness, inherited fragmented landholdings, minimum returns from agricultural activities, growing price of necessary commodities and increasing consumerist ideology have compelled simple rural male of the district to migrate in search of work elsewhere. In rural society of Cooch Behar district; women generally participate in food processing, child care, nursing, gossiping, and intensive agricultural task as helper. Temporary absence of man affects social status and life style of the women who are left behind both positively and negatively. -

DDRC Jalpaiguri10092018

5 4 3 2 1 SL.NO MIYA MIYA AKBAR ALI DHRUBA DHRUBA DUTTA PAYAL KHATUN PAYAL ANIMA ANIMA ROY PAYAL ROY PAYAL Name of beneficiary CAMP NAME : DDRC JALPAIGURI DATE : 10.09.2018 : DATE JALPAIGURI DDRC : NAME CAMP ROY,BARAKAMAT,JALPAIGUR TOLL,JAIGAON,JALPQAIGURI- PARA,BARUBARI,BERUBARI,J ROY,BAHADUR,JALPAIGURI- C/O C/O SAPIKUL ALAM,PURBA PARA,JALPAIGURI-735102 JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI JAFOR,JAYGAON,TRIBENI NAGAR,MOHANTA NAGAR,MOHANTA ALPAIGURI-735137 C/O C/O MIYA ABDUL DUTTA,MOHIT DUTTA,MOHIT C/O SHYAMAL C/O SHYAMAL C/O SANTOSH C/O SANTOSH LAL BAJAR C/O C/O BASI I-735305 735121 736182 Complete Address 14 14 48 65 11 Age M M F F F M/F GEN GEN OBC SC SC Caste 3500 3000 3000 3600 3000 Income HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING HEARING AID V AID V AID V AID V AID V Type of aid(given) 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 10.09.2018 Date on Which (given) 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total Cost of aid,including Fabrication/Fitment charges 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Subsidy provided Travel cost paid to outstation beneficiary Board and lodging expenses paid Whether any surgical correction undertaken 5680 5680 5680 5680 5680 Total of 10+11+12+13 No of days for which stayed Whether accomanied by escort YES YES YES YES YES Photo of beneficiary* 9002033171 9434228632 7076669744 9832340736 9932546247 Mobile No. or lan d line number with STD Code** C/O BABLU ROY,DHUPGURI,UTTAR HEARING 6 SIMA ROY 7 F SC 4000 10.09.2018 5680 100% 5680 YES 8512999121 KATHULIYA,JALPAIGURI- AID V 735210 C/O MADHUSUDAN APARNA CHAKRABORTY,ADARPARA HEARING 7 16 F GEN 2000 10.09.2018 5680 -

Intra-District Educational Scenarios in North Bengal, W.B., India Jayatra Mandal Part-Time Lecturer, Dept

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-6, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Intra-District Educational scenarios in North Bengal, W.B., India Jayatra Mandal Part-time Lecturer, Dept. of Geography, P. K. H. N. Mahavidyalaya, Howrah, W.B. Abstract: Education is fundamental in maintaining economic growth, infrastructure and INTRODUCTION social development. Naturally, availability of existing educational institutions of block level Development of a region, country or a district has plays important role to delineate the balanced or various facets. Broadly speaking development imbalanced scenario of the district. constitutes the elements like economic growth, In this paper seven districts of north Bengal were infrastructure and social development. The status assessed for identification of deficient blocks by of education is an integral part of social residual mapping. The co-efficient of correlation development. Education is an important avenue (r) and the coefficient of determination (r 2) ware which provides a wide range of opportunities for used for determined of degree of relationship all round development. Recognizing the value of between educational institution and total education, our central government has always tried population. to reconstruct the educational system for The result show that the blocks of Mirik, Matigara, betterment of the masses. Deep attention was paid Naxalbari, Kharibari and Phansidewa in to education as a factor vital to national progress Darjiling; Rajganj and Dhupguri in Jalpaiguri; and security. For the harmonious development of Madarihat-Birpara and Kalchini in Alipurduar; the society, education is imparted in different Mathabhanga-I, Mathabhanga-II, Sitalkuchi, levels through various institutions. In West Bengal Coochbehar-II, Dinhata –I and Sitai in Koch the general educational structure is divided into Bihar; Goalpokhar-I and Karandighi in Uttar five stages, viz. -

Dr. Arindam Metia Department of MBA Raiganj University Raiganj, Uttar Dinajpur/ Pin-733134 Mobile-9474592456 [email protected]

Dr. Arindam Metia Department of MBA Raiganj University Raiganj, Uttar Dinajpur/ Pin-733134 Mobile-9474592456 [email protected] Area of teaching interest Accounting & Taxation Present Status: Assistant Professor- Dept. of MBA, Raiganj University- Joined24th January, 2020 Education: Ph.D-University of North Bengal Title of the thesis: Role of Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan for Achieving the Education for All (EFA)”A study of Rural & Urban Areas of Jalpaiguri District SLET -2001 Master of Commerce Specialization in Accounting, University of Calcutta (2000) Bachelor of Commerce Hons. in Accountancy-1997, A.C.College of Commerce. Jalpaiguri, WB Research & Publication: Metia, A. (2019). Assessing MDM Hygiene & Satisfaction: A study with special Reference to Jalpaiguri Municipality. International Journal of management, Technology and Engineering , 391-403. Metia, A. (2019). Assessment of Primary school infrastructure : A Study of Rural & Urban Areas of Jalpaiguri District. The International journal of Analytical Experimental Model Analysis , 501-510. Metia, A. (2016). Education for All in Jalpaiguri with special reference to Infrastructure & RTE Act,2009: Current Status & Initiatives. Abhinav National Monthly Referred journal of research in Art & Education , 29-36. 1 Metia, A. (2019). Evaluation of MDM scheme between Jalpaiguri Municipality ( urban)& Rajganj(Rural) in West Bengal. journal of Emerging Technologies and innovative Research , 604-610. Metia, A. (2019). income tax Practice-A creator of Disparities. National Managemr Research Conference ,SIT (pp. 8-15). Siliguri, SIT. Metia, A. (2019). Perspective of Investment Decision of salaried people in Private Sector: A Study with Special reference to jalpaiguri town in West Bengal. International Journal of Engineering Development & Research) , 819-825. Metia, A. -

Tribal Women in the Democratic Political Process a Study of Tribal Women in the Dooars and Terai Regions of North Bengal

TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DEMOCRATIC POLITICAL PROCESS A STUDY OF TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DOOARS AND TERAI REGIONS OF NORTH BENGAL A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy In Department of Political Science By Renuca Rajni Beck Supervisor Professor Manas Chakrabarty Department of Political Science University of North Bengal August, 2018 Dedicated To My Son Srinjoy (Kutush) ABSTRACT Active participation in the democratic bodies (like the local self-government) and the democratic political processes of the marginalized section of society like the tribal women can help their empowerment and integration into the socio-political order and reduces the scope for social unrest. The present study is about the nature of political participation of tribal women in the democratic political processes in two distinctive areas of North Bengal, in the Dooars of Jalpaiguri district (where economy is based on tea plantation) and the Terai of Darjeeling district (with agriculture-based economy). The study would explore the political social and economic changes that political participation can bring about in the life of the tribal women and tribal communities in the tea gardens and in the agriculture-based economy. The region known as North Bengal consists of six northern districts of West Bengal, namely, Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Malda, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur and Cooch Behar. There is more than 14.5 lakh tribal population in this region (which constitutes 1/3rd of the total tribal population of the State), of which 49.6 per cent are women. Jalpaiguri district has the highest concentration of tribal population as 14.56 per cent of its population is tribal population whereas Darjeeling has 4.60 per cent of its population as tribal population. -

Preparation of Crop Calendar on Mangalbari Town Under Matiali Block, Jalpaiguri District Amit Banerjee1, Dr

International Journal of Environmental & Agriculture Research (IJOEAR) ISSN:[2454-1850] [Vol-6, Issue-12, December- 2020] Preparation of Crop Calendar on Mangalbari Town under Matiali Block, Jalpaiguri District Amit Banerjee1, Dr. Suma Dawn2 1Post Graduate Student (Department of Geography), The University of Burdwan, Barddhaman-713104 1 ORCID : 0000-0002-0687-4951 2Assistant Professor (Department of Geography), Triveni Devi Bhalotia College, Raniganj- 713347 Abstract— The crop calendar in a single word is time-table providing periodical information of sowing, growing and harvesting of different crops in relation to the climatic conditions of a particular area in advance. It also enhances the crop productivity and determines the appropriate distribution of labor, application of manures in the field as well as the wholesome development of the agronomy of a specific area. The present work is an effort to highlight the present pattern of agricultural practice as well as to identify different types of crops are produced in the Mangalbari town of Jalpaiguri, West Bengal. The investigation also focuses on the assessment of crop combination, crop specialization & crop diversification in the study area to end with the preparation of crop calendar. The entire work concludes with précised suggestive measure for the development of agronomy in the area. Keywords— Crop Calendar, Crop Combination, Crop Specialization, Crop Diversification, Agronomy. I. INTRODUCTION 'Crop Calendar' is a tool as well as a completion of work that provides timely information about seeds to promote local crop production. This tool contains information on planting, sowing, and harvesting menses of locally adapted crops in particular agro-ecological zones. It also provides information on the sowing rate of seeds and planting equipment, and the staple agricultural practices. -

Capability and Well-Being in the Dooars Region of North Bengal

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Majumder, Amlan Book — Published Version Capability and Well-Being in the Forest Villages and Tea Gardens in Dooars Region of North Bengal Suggested Citation: Majumder, Amlan (2014) : Capability and Well-Being in the Forest Villages and Tea Gardens in Dooars Region of North Bengal, ISBN 978-93-5196-052-2, Majumder, Amlan (self-published), Cooch Behar, India, http://amlan.co.in/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/Amlan_Majumder- eBook-978-93-5196-052-2.11162659.pdf This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110898 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content