Humour and Colonialism Krebs CPSA Final Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One of Our Country's Top Comics!

DDAARRCCYY MMIICCHHAAEELL “One of our country’s Top Comics!” -Georgia Straight “I fell asleep…Twice!” -Darcy’s Mom BIO Dominating the Comedy scene for over 10 years, Darcy Michael continues to prove his voice is one like no other. Pegged by the Montreal Gazette as one of their favourites at the prestigious Just for Laughs Festival - he has gone on to appear there for 7 consecutive years. With 10 national televised festival Gala appeareances in 2018 Just for Laughs partnered with Bell Media and Darcy Michael to film their first ever 1 hour stand up special called “Darcy Michael Goes to Church” available for streaming now on CraveTV.ca. After 2 seasons starring opposite Dave Foley in CTV’s “Spun Out”, Darcy released his latest album “Family Highs” which quickly debuted #1. After Spun Out, CTV & Project 10 Productions announced a deal to develop “Darcy,” a single-cam sitcom based on Darcy Michael’s life and stand up. Twice nominated for a Canadian Comedy Award, Darcy’s edgy but personable approach has won him numerous appearances at the Just for Laughs Festival, Comedy Network’s Match Game, Winnipeg Comedy Festival, and regular appearances on CBC Radio’s ‘The Debaters.‘ After becoming a finalist in the national XM Top Comic Competition, Darcy toured with Russell Peters and after an international search by NBC was chosen as a finalist for the NBC’s Stand Up for Diversity show. The comedian/actor currently resides in Ladner, BC, with Jeremy, his husband of 14 years and their daughter. If Darcy isn’t on stage or filming, he can probably be found tending to his garden…where he grows “vegetables.” T: @thedarcymichael W: www.DarcyMichael.com . -

Russell Peters: Red, White and Brown' DVD and CD Hitting Stores on Tuesday, January 27

COMEDY CENTRAL Home Entertainment(R) Releases 'Russell Peters: Red, White And Brown' DVD and CD Hitting Stores on Tuesday, January 27 20 Minutes Longer Than The Broadcast Version, DVD Arrives Packed With Hilarious Feature Commentary By Russell Peters, Clayton Peters And Director Jigar Talati, A "Support the Troops" Bonus Feature With Commentary, Deleted Scenes And More Audio CD Also Included NEW YORK, Jan. 14 -- Russell Peters is back in the all-new stand-up special, "Red, White And Brown." With his perfect balance of sophisticated writing and physicality, it's clear why Russell Peters is one of today's most internationally respected comedians. Released via COMEDY CENTRAL Home Entertainment and Paramount Home Entertainment, "Russell Peters: Red, White And Brown" DVD and CD arrives in stores nationwide on Tuesday, January 27 and will also be available at http://shop.comedycentral.com. The "Russell Peters: Red, White And Brown" DVD is a new stand-up special that was taped at the WaMu Theatre at Madison Square Garden in New York City. Bonus materials include Feature Commentary by Russell Peters, Clayton Peters and Director Jigar Talati, deleted scenes, "Support the Troops" Bonus Feature with commentary and a "White Jacket Bootleg" segment with commentary and includes an audio version of the special on CD. Russell Peters is already a comedy superstar in much of the world. During a recent tour of Dubai, Peters sold tickets at the rate of one ticket every two seconds -- crashing all the online sales outlets as soon as the tickets went on sale. In April 2005, Peters was the first South Asian to headline and sell out the Apollo Theatre in New York City. -

Smart Cinema As Trans-Generic Mode: a Study of Industrial Transgression and Assimilation 1990-2005

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Smart cinema as trans-generic mode: a study of industrial transgression and assimilation 1990-2005 Laura Canning B.A., M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2013 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 58118276 Date: ________________ 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p.6 Chapter Two: Literature Review p.27 Chapter Three: The industrial history of Smart cinema p.53 Chapter Four: Smart cinema, the auteur as commodity, and cult film p.82 Chapter Five: The Smart film, prestige, and ‘indie’ culture p.105 Chapter Six: Smart cinema and industrial categorisations p.137 Chapter Seven: ‘Double Coding’ and the Smart canon p.159 Chapter Eight: Smart inside and outside the system – two case studies p.210 Chapter Nine: Conclusions p.236 References and Bibliography p.259 3 Abstract Following from Sconce’s “Irony, nihilism, and the new American ‘smart’ film”, describing an American school of filmmaking that “survives (and at times thrives) at the symbolic and material intersection of ‘Hollywood’, the ‘indie’ scene and the vestiges of what cinephiles used to call ‘art films’” (Sconce, 2002, 351), I seek to link industrial and textual studies in order to explore Smart cinema as a transgeneric mode. -

How Ninja from Die Antwoord Performs South African White Masculinities Through the Digital Archive

ZEF AS PERFORMANCE ART ON THE ‘INTERWEB’: How Ninja from Die Antwoord performs South African white masculinities through the digital archive by Esther Alet Rossouw Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM in the Department of Drama Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr M Taub AUGUST 2015 1 ABSTRACT The experience of South African rap-rave group Die Antwoord’s digital archive of online videos is one that, in this study, is interpreted as performance art. This interpretation provides a reading of the character Ninja as a performance of South African white masculinities, which places Die Antwoord’s work within identity discourse. The resurgence of the discussion and practice of performance art in the past thirty years has led some observers to suggest that Die Antwoord’s questionable work may be performance art. This study investigates a reconfiguration of the notion of performance art in online video. This is done through an interrogation of notions of risk, a conceptual dimension of ideas, audience participation and digital liveness. The character Ninja performs notions of South African white masculinities in their music videos, interviews and short film Umshini Wam which raises questions of representation. Based on the critical reading of Die Antwoord’s online video performance art, this dissertation explores notions of Zef, freakery, the abject, new ethnicities, and racechanges, as related to the research field of whiteness, to interpret Ninja’s performance of whiteness. A gendered reading of Die Antwoord’s digital archive is used to determine how hegemonic masculinities are performed by Ninja. It is determined that through their parodic performance art, Die Antwoord creates a transformative intervention through which stagnant notions of South African white masculinity may be reconfigured. -

Kent Academic Repository Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Declercq, Dieter (2018) What is satire? . Blog. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/75358/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html AESTHETICS FOR BIRDS ABOUT Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art for Everyone STAFF POSTS GUEST POSTS PROFESSIONAL MATTERS INTERVIEWS JAAC X AFB "Aesthetics is for the artist as JAAC x AFB: WHAT IS SATIRE? ornithology is for the birds." - September 6, 2018 by aestheticsforbirds | Leave a comment Barnett Newman SEARCH Flock Leader Alex King Wing Commanders Rebecca Victoria Millsop C. Thi Nguyen Birds What follows is a post in our ongoing collaborative series with the Journal of Aesthetics and Roy Cook Nick Stang Art Criticism. This is based on a new article by Dieter Declercq, “A Definition of Satire (And Matt Strohl Why a Definition Matters)” which you can find in the current issue of JAAC. -

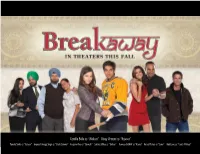

Vinay Virmani As

Camilla Belle as “Melissa” Vinay Virmani as “Rajveer” Pamela Sinha as “Jasleen” Gurpreet Ghuggi Singh as “Uncle Sammy” Anupam Kher as “Darvesh” Sakina Jaffrey as “Livleen” Noureen DeWulf as “Reena” Russell Peters as “Sonu” Rob Lowe as “Coach Winters” FEATURE SHEET Form: Feature Film Genre: Family, Cross Cultural, Comedic Drama Runtime: 95 min Date of Completion: June 30th, 2011 Expected to be Premiered at TIFF (Toronto International Film Festival) September 2011 Country of Production: Canada Country of Filming: Canada Production Budget: $12M CDN Producers / Fund Source: Hari Om Entertainment, First Take Entertainment Whizbang Films, Caramel Productions Don Carmody Productions, TeleFilm Canada CBC TV (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) Distribution: Canada – Alliance Films India – Hari Om Entertainment All other international territories currently available LEAD CAST Vinay Virmani as Rajveer Singh Russell Peters as Sonu Camilla Belle as Melissa Winters Anupam Kher as Darvesh Singh Rob Lowe as Coach Dan Winters Sakina Jaffrey as Livleen Singh Gurpreet Ghuggi as Uncle Sammy Noureen DeWulf as Reena Cameo Appearances Akshay Kumar Aubrey “DRAKE” Graham Chris “LUDACRIS” Bridges SYNOPSIS BACKGROUND: BREAKAWAY, is a cross-cultural hockey drama set in the Indo-Canadian community in suburban Toronto, Canada. The movie is a full action, colourful, humourous, heart-felt musical. The setting is an obstacle-strewn love story with a dramatic quest for the hero. It’s also a keenly observed cross-cultural drama in the same classification as Bend It Like Beckham and Slumdog Millionaire with a hero caught between a family’s traditional expectations and a dream to make it big in the national sport of an adopted country. -

Global Media Seminar

Global Media Seminar Class code MCC-UE 9456 – 001 Instructor Sacha Molitorisz Details [email protected] Consultations by appointment Please allow at least 24 hours for your instructor to respond to your emails. Class Details Spring 2017 Global Media Seminar Wednesday 9:00am – 12:00pm February 1 to May 10 Room 302 NYU Sydney Academic Centre Science House: 157-161 Gloucester Street, The Rocks 2000 Prerequisites None Class This course examines the fast-changing landscape of global media. Historical and theoretical Description frameworks will be provided to enable students to approach the scope, disparity and complexity of current developments. These frameworks will be supplemented with the latest news and developments. In short, we ask: what is going on in the hyperlinked and hyper- turbulent realm of blogs, Buzzfeed and The Sydney Morning Herald? Key issues examined include: shifts in patterns of production, distribution and consumption; the implications of globalisation; the disruption of established information flows and emergence of new information channels; the advent of social media; the proliferation of mobile phones; the ethics and regulation of modern media; the rise of celebrity culture; the demise (?) of privacy; the entertainment industry and its pirates; Edward Snowden and the NSA; and the irrepressible octogenarian Rupert Murdoch. The focus will be international, with an emphasis on Australia. Ultimately, the course will examine the ways in which global communication is undergoing a paradigm shift, as demonstrated by the Arab spring and its uncertain legacy, as well as the creeping dominance of Google, Facebook and Twitter. In other words Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore. -

January 2009 Highlights

www.comedychannel.com.au JANUARY 2009 HIGHLIGHTS 1. Graham Kennedy’s Blankety Blanks (Part of AUSSIE GOLD) 2. New Year’s Day Animania 3. Australia Day South Park Marathon GRAHAM KENNEDY’S BLANKETY BLANKS Part of AUSSIE GOLD CHANNEL PREMIERE Fridays at 7.30pm from January 2 The King of Australian comedy Graham Kennedy is joining AUSSIE GOLD, THE COMEDY CHANNEL’s television BBQ of the greatest and timeless Australian comedy favourites! Graham Kennedy is at the height of his irreverent hilarity, whilst pushing the boundaries of acceptable taste with an armada of jokes about Cyril and Dick, in this legendary television hit. Despite, or perhaps in part thanks to, being labelled “vulgar smut” by the press, BLANKETY BLANKS quickly became the highest rating show on Australian television. In the late ‘70s there was simply no other place for Australian viewers to be as Kennedy turned the game show format into a 30 minute tour de force of double entendres and outrageous comic brilliance. A game show, in theory, but one that places the contestants in distant third place behind the hilarious antics of Gra-Gra and his regular cast members Ugly Dave Gray, Stuart Wagstaff, Noelene Brown, Carol Raye, Barry Creyton and Noel Ferrier. In addition to being presided over by legendary producer Tony the Moustache Twirler and with anonymous contributions from the enigmatic Peter the Phantom Puller, BLANKETY BLANKS rotates through a roster celebrity guest stars forming a who’s who of Australian ‘70s entertainment - Abigail, Delvene Delaney, June Salter, Peta Toppano, Mark Holden, Tommy Hanlon Jr, John Paul Young, Debbie Byrne, Marty Rhone and anyone else who was up for the ribald fun. -

The Sundae Presents Ciara Moloney

The Sundae presents God Sent Me To Piss The World Off Ciara Moloney Intro 3 I’m just relaying what the voice in my head’s saying. Don’t shoot the messenger. 4 How many records you expecting to sell after your second LP sends you directly to jail? 15 Though I’m not the first king of controversy, I am the worst thing since Elvis Presley. 29 I’m a piece of fucking white trash, I say it proudly. 38 Eminem is an underground horrorcore rapper who, through some mix-up in the cosmic order, instead became the best-selling artist of the 2000s. To remember how incredibly big Eminem became in the late 1990s and early 2000s while rapping about killing himself, raping his mother, and murdering his wife seems like peering into some long-distant era: much further away than twenty years should be, more like a time memorialised only in photographs and letters. But that’s not quite right, either. It’s less like a far away past than a hole torn in the fabric of the universe, just wide enough to let a single impossible thing leak through. Eminem managed to feel dangerous even as he became ubiquitous, at once a fact of life and a radical notion that must be supressed at all costs. That tension is one of the defining features of Eminem’s discography: both boundary-pushing and mainstream, both snotty, scrappy underdog and superstar. Listening to his early albums, it seems at times like he’s trying to Tom Green himself and see what he has to say to get kicked out of the music industry. -

Resume Wizard

Class code MCC-UE 9456 001 Instructor Details Sacha Molitorisz [email protected] 0423 306 769 Consultations Tuesdays after class by appointment. Class Details Global Media Seminar Tuesdays: 9.30am - 12.30pm. NYU Sydney Academic Centre Science House, 157 Gloucester St, The Rocks. Prerequisites None Class Description This course brings together diverse issues and perspectives in rapidly evolving areas of international/global communication. Historical and theoretical frameworks will be provided to help students approach the scope, disparity and complexity of current developments in the media landscape. These frameworks will be supplemented with the latest media news and developments, often in relation to pop culture. Students will be encouraged to think critically, assessing shifts in national, regional and international media patterns of production, distribution and consumption over time. The aim is to come to an understanding of the tumultuous contemporary global communication environment. The key concepts under examination include: trends in national and global media consolidation; the radical cultural implications of globalisation; the disruption of established information flows and the emergence of new information channels; the ethics, law and regulation of modern media; and trends in communication and information technologies. Specific issues addressed include: the rise of celebrity culture; the challenges facing the entertainment industry; and the rise, rise and potential demise of Rupert Murdoch. The focus will be international, with a particular emphasis on Australia. Ultimately, the course will examine the ways in which global communication is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, as demonstrated by the Arab spring, the Olympics coverage and the creeping dominance of Google, Facebook and Twitter. -

1 a Queer Tension

1 A Queer Tension: The difficult comedy of Hannah Gadsby’s Nanette Live Olu Jenzen Introduction This article concerns itself with feminist comedy that is deemed angry and difficult, yet has had critical and commercial success. Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up show Nanette Live1 can be described as difficult because it is politically challenging, emotionally demanding and disrupts the established format of stand-up comedy. Nanette challenges the underpinning assumption of postfeminism: that feminism is no longer needed.2 It is feminist and angry. Which, arguably, does not have an obvious place in today’s popular culture where comedians are expected to be postfeminist. An example of cultural expectations in the postfeminist era is the figure of the female comedian as an ‘empowered’ individual who is seen as a product of feminism, because she can take centre stage and speak out, whilst dismissing the need for feminism in her comedy. Another example would be the reframing and revalidation of sexist jokes – what Susan Douglas calls ‘enlightened sexism’, whereby the assumption that full gender equality has been achieved, makes it ‘okay, even amusing, to resurrect sexist stereotypes of girls and women’.3 To explore the phenomenon of angry feminist comedy in the postfeminist era further, the article considers the comedy of Gadsby through the prism of the figure of the feminist killjoy4, asking what place the feminist killjoy has in comedy? It also draws a different take on the figure of the feminist killjoy as outlined by Jack Halberstam in Queer Art -

Computational Analysis of Humour

Computational Analysis of Humour Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Exact Humanities by Research by Vikram Ahuja 201256040 [email protected] International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad - 500 032, INDIA July 2019 Copyright c Vikram Ahuja, 2019 All Rights Reserved International Institute of Information Technology Hyderabad, India CERTIFICATE It is certified that the work contained in this thesis, titled “Computational Analysis of Humour” by Vikram Ahuja, has been carried out under my supervision and is not submitted elsewhere for a degree. Date Adviser: Prof. Radhika Mamidi To my Parents and Late Prof. Navjyoti Singh Acknowledgments I would like to thank Prof. Radhika Mamidi for accepting me to complete my thesis under her guidance. I would like to thank Late Prof. Navjoyti Singh, my advisor for accepting me in IIIT-H and for his constant support, guidance and motivation. Working under him was a great learning experience. He promoted free thought, exploration and has pushed me to think out of the box. I thank my parents and Rubal for their unconditional love and support throughout the journey. I would like to extend my warm regards to all the research members at CEH for their help. I would specially like to thank Taradheesh Bali for his inputs, being an awesome research partner and for being my co-author. I would like to thank all my friends and my hostel mates for making my journey in IIIT-H more exciting. A special shoutout to Manas Tewari for helping me reviewing my thesis and most of my research work.