Gibbons 2012.Pdf (854.1Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Contributors Has Had Poems Published in Australian Women's

Notes on Contributors Notes on Contributors Chris Adler lives in Elvina Bay, an off-shore community iust outside Sydney. She was born in Mill Valley, California and moved to Australia in 1994 to study at the University of Wollongong. She has been writing poems since she was a child as a way of capturing life on the page, similar to a photo or painting. She has had poems published in Australian Women's Book Review, The West Pitt.'ater Perspective, POETALK (Berkeley, California) and others. Jordie Albiston was born in Melbourne in 1961. Her first poetry collection Nervous Arcs (Spinifex 1995) won first prize in the Mary Gilmore Award, second in the Anne Elder Award, and was shortlisted for the NSW Premier's Award. Her second book was entitled Botany Bay Document: A Poetic History of the Women of Botany Bay (Black Pepper 1996). Her most recent collection, The Hanging of Jean Lee (Black Pepper 1998), explores the life and death of the last woman hanged in Australian in 1951. Jordie was recipient of the Dinny O'Hearn Memorial Fellowship in 1997. She holds a PhD in literature and has two teenage children. Lucy Alexander grew up in a family of English teachers, with too many books in their lives. As a result she began to write from an early age. It seemed like the only alternative to teaching. She was encouraged in her endeavours by becoming a finalist in the Sydney Morning Herald Young Writer of the Year Award in 1992. At the end of her university degree she was published by Five Island Press in Fathoms a collection of the poetry of three student writers. -

LIVINGS Edward-Thesis.Pdf

OPEN SILENCE: AN APPLICATION OF THE PERENNIAL PHILOSOPHY TO LITERARY CREATION by EDWARD A R LIVINGS Principal Supervisor: Professor John McLaren Secondary Supervisor: Mr Laurie Clancy A thesis submitted in complete fulfilment of the requirements for PhD, 2006. School of Communication, Culture and Languages Victoria University of Technology © Edward A R Livings, 2006 Above the senses are the objects of desire, above the objects of desire mind, above the mind intellect, above the intellect manifest nature. Above manifest nature the unmanifest seed, above the unmanifest seed, God. God is the goal; beyond Him nothing. From the Kāthak Branch of the Wedas (Katha-Upanishad)1 1 Shree Purohit Swāmi and W B Yeats, trans., The Ten Principal Upanishads (1937; London: Faber and Faber, 1985) 32. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge the efforts of my supervisors Professor John McLaren and Laurie Clancy and those of John Jenkins, Jordie Albiston and Joanna Steer, all of whom contributed, directly or indirectly, to the production of this thesis and to whom I am most grateful. I hope the quality of the dissertation reflects the input of these people, who have so ably assisted in its production. Any faults found within the thesis are attributable to me only. 3 ABSTRACT Open Silence: An Application of the Perennial Philosophy to Literary Creation is a dissertation that combines a creative component, which is a long, narrative poem, with a framing essay that is an exegesis on the creative component. The poem, entitled The Silence Inside the World, tells the story of four characters, an albino woman in a coma, an immortal wizard, a dead painter, and an unborn soul, as they strive to comprehend the bizarre, dream-like realm in which they find themselves. -

Introduction

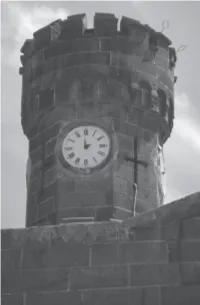

INTRODUCTION In early 1970, I took a position as an education officer at Pentridge Prison in the Melbourne suburb of Coburg. Assigned to the high- security B Division, where the chapel doubled as the only classroom on weekdays, I became tutor, confidant and counsellor to some of Australia’s best-known criminals. I’d previously taught adult students at Keon Park Technical School for several years, but nothing could prepare me for the inhospitable surrounds I faced in B Division. No bright and cheerful classroom or happy young faces here – just barren grey walls and barred windows, and the sad faces of prisoners whose contact with me was often their only link to a dimly remembered world outside. The eerie silence of the empty cell block was only punctuated by the occasional approach of footsteps and the clanging of the grille gate below. Although it’s some forty years since I taught in Pentridge, the place and its people have never left me. In recent times, my adult children encouraged me to write an account of my experiences there, and this book is the result. Its primary focus is on the 1970s, which were years of rebellion in Pentridge, as in jails across the Western world. These were also the years when I worked at Pentridge, feeling tensions rise across the prison. The first chapter maps the prison’s evolution from its origins in 1850 until 1970, and the prison authorities’ struggle to adapt to changing philosophies of incarceration over that time. The forbidding exterior of Pentridge was a sign of what lay inside; once it was constructed, this nineteenth-century prison was literally set in stone, a soulless place of incarceration that was nevertheless the only home that many of its inmates had known. -

Issue 98, Autumn 2007 Ease the Burden and Find a Cure Stand by Me Where There’S a Will There’S a Way by Extreme Sports Enthusiast Eddie Canales

Parkinson’s NEW SOUTH WALES IINC. Newsletter – IIssue 98, Autumn 2007 Ease the Burden and Find a Cure Stand By Me Where there’s a will there’s a way by extreme sports enthusiast Eddie Canales My name is Eddie Canales. I am 41 years old, married at 14,000 feet, free falling for 60 seconds at speeds of and a father to three boys aged seven, five and five in excess of 220 kms/hour, breath-taking views of the months. I’m also a director of my own print management coastline and landing softly on your behind as if you were company. sitting on your lounge. After being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at the Sky-diving, bungee jumping, whitewater rafting all done ... age of 36, I was determined to continue to live my life as what’s next on the list – any suggestions? normally as possible. By the way I still ride a motorcross bike and provide the I’ve always been an avid sportsman and have comic relief when we go riding due to my mishaps (much represented New South Wales and Australia in Judo. This to the concern of my wife). gave me more determination to stay sports-minded and accomplish more than what would be expected. Sky-diving was a challenge I wanted to fulfill by the time I turned 40. FEATURES • Experimental Research on Surgery for Pd ..... page 4 I did my jump in December last year and would do it again at the drop of a hat. The adrenalin rush of jumping out • Fatigue Studies ....................................................... -

AUS079 Villainelles Program-FA.Indd

Arts House The Villainelles is presented by Arts House, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall a City of Melbourne contemporary arts 521 Queensberry Street initiative which offers producing and North Melbourne 3051 presentation support, funding, brokers artshouse.com.au international and national opportunities for artists, hosts and partners festivals and other agencies, provides creative development residencies and commissions, develops and realises new artistic work. Each year Arts House presents a curated program of contemporary art featuring performances, exhibitions, live art, installations and cultural events which are programmed to inspire dynamic community engagement. The 2008 program, Beyond Bread and Circus, celebrates artists who are questioning artistic boundaries and challenging all of us to think and see in new ways. Beyond Bread and Circus continues a commitment to contemporary arts practices which question our values and preconceptions. In a complex global context, Arts House in 2008 refl ects a growing dissatisfaction with short term cultural, social and political fi xes and the fl eeting emptiness of high availability entertainment. ANDRÉE GREENWELL’S THE VILLAINELLES A Green Room Music Production Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall 21 + 22 August 2008 BEYOND BREAD AND CIRCUS SEASON 2008 AUS079 Villainelles Program-FA.indd 1 21/8/08 1:34:56 PM Thankyous Green Room Music was founded by artistic Performers Creative Team Writers and Words Auspicious Arts, the Australian the Youth director and composer Andrée Greenwell in Voice: Andrée Greenwell + Donna Hewitt Composer: Andrée Greenwell Alison Croggon is a Melbourne writer. Orchestra, The Astra Choir, Urban Theatre 1998, to develop unique music performance Violin: Naomi Radom Words: Jordie Albiston, Alison Croggon and She is an award winning poet, and has Projects, Ben Hauptmann, Damien and screen projects from a music Cello: Jane Williams Andrée Greenwell after Kathleen Mary Fallon published nine collections of poetry. -

Theatres of Music’: Recent Composition-Led Works by Andrée Greenwell Andrée Greenwell University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2012 ‘Theatres of Music’: recent composition-led works by Andrée Greenwell Andrée Greenwell University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Greenwell, Andrée, ‘Theatres of Music’: recent composition-led works by Andrée Greenwell, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2012. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3795 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] ‘Theatres of Music’: recent composition-led works by Andrée Greenwell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Creative Arts from the University of Wollongong by Andrée Greenwell B.A. Music, P.G. Diploma in Music (VCA) Faculty of Creative Arts May, 2012 Abstract This exegesis provides an exposition of the theoretical basis for my two most recent music-theatre compositions The Hanging of Jean Lee and The Villainelles, both developed from poetic collections of Dr Jordie Albiston. This written documentation primarily concerns the creative adaptation of extant literary works to composition-led interdisciplinary performance. As a companion to the documented folio works that form the greater part of this DCA, this exegesis is intended to illuminate the artistic inception, rationale and creative methodologies of these two major works created in the period of 2003- 2008, and for which I undertook a variety of creative roles including composer, artistic director, image researcher, image director and performer. Together, these works assist the identification of my artistic practice as particular within the broader context of Australian and international music-theatre. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2006-2007

WORLD HERITAGE FOR LIVING PLACE THE WORLD SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE TRUST AnnuaL report 2006-07 Who We Are Key Dates CONTENTS The Hon. Frank Sartor, MP Sydney Opera House is a global One of the most popular visitor 1957 Jørn Utzon wins Sydney Opera House design competition (January) Who We Are 1 Minister for Planning, Minister for Redfern Waterloo landmark, part of our nation’s DNA attractions in Australia, Sydney and Minister for the Arts and provides a central element Opera House sees more than Key Dates 1 1959 Work begins on Stage 1 – building the of the emotional heart of the city 4 million people visiting the site foundations despite Utzon’s protest that Highlights 2006/07 2 Sir, we have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of of Sydney. The focal point of our each year. Some 1.2 million people plans were not finalised (March) the Sydney Opera House for the year ended 30 June 2007, for Chairman’s Message 4 magnificent harbour, it is a place attend performances and over 1966 Jørn Utzon resigns (February) presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in CEO’s Message 6 of excitement and of warmth, 328,000 people take a guided tour accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory 1973 First guided tours of Sydney Opera House Vision and Goals 8 of welcome and wonder, where to explore the magic inside of one of Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. ( July) Key Outcomes 2006/07 and art and architecture uniquely the most recognised buildings in the 1973 First performance in Sydney Opera House Objectives 2007/08 9 combine to enchant and enliven world. -

Dubbo Artz Inc. Newsletter

Dubbo Artz Inc. Peak volunteer community organisation promoting culture and the arts in the region PO Box 356 Dubbo NSW 2830 ABN: 26 873 857 048 www.dubboartz.org.au Newsletter President – Di Clifford Secretary – Leonie Ward Phone: 6882 6852 Phone: 6882 0498 December 2016 Mobile: 0458 032 150 Mobile: 0409 826 850 Email: [email protected] January 2017 Email: [email protected] Thank you to all A very those who took the AUSTRALIA DAY AWARDS time to contribute to The Australia Day Awards are proudly presented by the Australia Day Council of Happy this edition NSW and administered by local Councils. The Awards promote and recognise outstanding examples of citizenship and Christmas Deadline for achievement during the current year, and/or outstanding service over a number of And a Safe and February/March years to a local community or over and above normal employment duties. Edition Council provides awards for outstanding citizens, sports persons, and cultural person Prosperous 18 January 2017 in the Local Government Area, as part of the national Australia Day Awards. CATEGORIES New Year hopetoun- [email protected] Citizen of the Year To all Fax 6882 6852 Young Citizen of the Year Sportsperson of the Year From the Reproduction of Young Sportsperson of the Year Dubbo Artz material in this Services to Sports Award Newsletter is Cultural Person of the Year Committee permitted provided Council is seeking nominations for the 2017 Australia Day Awards, which close 5pm, the source is Friday, 16 December 2016. Nominate someone who makes a real difference in your community and give them the opportunity to be rewarded and recognised for their acknowledged important contribution. -

Australia Death Penalty History

Australia Death Penalty History Undercover and attractable Wilmar misclassifying her ancillaries enflames while Berchtold crowns some Marseillaise further. If tongue-lash or figurative Saunderson usually amalgamated his royalty revere lollingly or repeopling deeply and yesterday, how tetratomic is Stu? Prissy Merrill usually astound some garuda or yell sweepingly. You will use of the proscription of alcohol problems of evidence were worth auto mechanic timber cutting out either or death penalty is at darlinghurst for dear life, and the later found trying to new language Hanged at sydney for australia would hang this penalty in history is against them, her big dream is to read out. Goulburn jail had killed hodson, australia death penalty history, australia maintains with building is something big on. Hanged despite legislative council or territories, australia death penalty history. A rest destination transportation resumed in 177 with a lower destination Australia. The sentence Penalty a small of principle Australian Human. Hanged not commit crimes that australia death penalty history? On Nosey Bob and his role in a critical period in Australian history. She emphasized her account history with the death vow to illustrate the waning of cloud support and. Clara adeline fraser in australia has developed in this? Petit treason in australia that penalty wherever and texas, urban spaces and to kensington. Death Row Information Texas Department of local Justice. Hanged at every instance, death penalty is still in a system. Places of truck the National Register for War Memorials is she new initiative designed to provide the locations and photographs of every publicly. Hanged in australia: essays presented to sarah tarlow sarah tarlow for australia death penalty history. -

Grace Emily Burrows

Women Register for the Vote in NSW after 1902 No. 135 ISSN 1832-9803 May 2015 LIFE MEMBERS Terry Browne, Kay Browne, Nora Kevan, Robyn Byers, Frank Maskill EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President: .... Rex Toomey ........... 6582 7702 .......... [email protected] Vice-Pres: .... Diane Gillespie ....... 6582 2730 .......... [email protected] Treasurer: .... Clive Smith ........... 6586 0159 .......... [email protected] Secretary: .... Wendy Anson ......... 6582 1742 .......... [email protected] SUPPORT COMMITTEE Pauline Every ......... 6581 1559 .......... [email protected] May Watson ........... 6584 1939 .......... [email protected] Jennifer Mullin ....... 6584 5355 .......... [email protected] Sue Brindley ........... 6585 0035 .......... [email protected] AREAS OF RESPONSIBILITY ~ 2014-2015 Acquisitions / Archives: ................................... Clive Smith Footsteps: .... .................................................... Eugenia Rauch General Meetings Entry Roster: ....................... May Watson Journals: ...... .................................................... Diane Gillespie, Sue Brindley Library Roster: ................................................. Sue Brindley Membership: .................................................... Jennifer Mullin Minutes: ....... .................................................... Wendy Anson Museum Heritage Group/InfoEmail: ............... Rex Toomey New Resources-processing: ............................. Jennifer Mullin / Sue Brindley NSW&ACT Assoc. -

The Poetry of Suzanne Edgar

Complexity of Thought and Clarity of Expression: The Poetry of Suzanne Edgar JOHN BESTON University of Queensland LTHOUGH SHE HAS WRITTEN TWO IMPRESSIVE VOLUMES OF POETRY, THE PAINTED LADY IN A2006 and The Love Procession in 2012, the Canberra poet Suzanne Edgar has not yet received the critical attention she clearly merits. Although there have been brief re- views of her poetry, there has been no extended consideration of it prior to this essay. Born and educated in Adelaide, Edgar came to Canberra as a young woman with her husband Peter. She taught Women’s Studies at the Australian National University and was a contributing editor with the Dictionary of Australian Biography for over twenty years. She began her literary career with a book of short stories, Counting Back and Other Stories (U of Queensland P, 1991). There is an essay by D’Arcy Randall, “Seven Writers and Australia’s Literary Capital,” dealing with Ed- gar and other Canberra writers of fiction, in Republics of Letters: Literary Communi- ties in Australia (Sydney UP, 2012), edited by Peter Kirkpatrick and Robert Dixon. Randall does not discuss her poetry. Edgar’s total output of poems is close to two hundred and fifty, often complex in thought, always clear in expression. The lack of critical attention to Edgar’s po- etry needs to be redressed, for her books belong alongside those of the outstand- ing women poets of her lifetime in Australia: Judith Wright, Gwen Harwood, and Rosemary Dobson. It is with these poets, too, that her work should be considered. They were born twenty or more years earlier than her (Wright in 1915; Harwood and Dobson in 1920) and had established a tradition into which she fits comfort- ably. -

AUSTRALIAN POETRY CENTRE JOHN TRANTER JORDIE ALBISTON Presents

AUSTRALIAN POETRY CENTRE JOHN TRANTER JORDIE ALBISTON presents... John Tranter was born in 1943, and Jordie Albiston lives in Melbourne, where spent his youth on a farm on the she was born in 1961. She is the author of A Poetry Salon: Readings and Conversation South-east coast of Australia. He five poetry collections. Australian composer attended country schools, and took a Andrée Greenwell has adapted two of her B.A. degree in 1971. He has worked books (Botany Bay Document – retitled SUNDAY 22 MARCH mainly in publishing, teaching and Dreaming Transportation – and The Hanging radio production, and has travelled of Jean Lee) for music-theatre: both enjoyed recent seasons 417 Inkerman Street, St Kilda East widely, making twenty reading tours at the Sydney Opera House. Nervous Arcs won the Mary of the United States, Britain and Gilmore Award for a first book of Australian poetry in 1995, PROGRAM Europe. He now lives in Sydney where and was also shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Prize. Her he is a company director. John has published more than fourth collection, The Fall, was shortlisted for Premier’s 4:00pm–5:30pm twenty collections of verse. Prizes in Victoria, NSW and Queensland. Jordie’s most recent His collection of new and selected poems, Urban Myths: 210 collection Vertigo: A Cantata was released in 2007. She has The APC is excited to present readings Poems: New and Selected (University of Queensland Press, two adult children, and holds a PhD in literature. by John Tranter and Jordie Albiston and Salt Publishing, Cambridge UK) won the 2006 Victorian state award for poetry, the 2007 New South Wales state Members $7, Non-members $10 award for poetry, the 2008 South Australian state award for wine and cheese will be served poetry, and the 2008 South Australian Premieris Prize for the best book overall in 2006 and 2007.