Discourse Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marshall Mcluhan

Marshall McLuhan: Educational Implications* W.J. Gushue He received the Governor General's award for his work in literature, the Albert Schweitzer Chair at Fordham for his work in communications, and the Moison Award from the Canada Council as "explorer and interpreter of our age." He appeared on the covers of N eW8week, Saturday Review and Canada's largest weekend supplement. NBC made a one-hour docu mentary of his message and later repeated it, and the CBC gave him prime Sunday night viewing time on two occasions. He is one of the most publicized intellectuals of recent times. Ralph Thomas wrote in the Torfmto Star: "He has been explained, knocked and praised in just about every magazine in the EngIish, French, German and Italian languages." 1 As to newspaper coverage, which newspapers have not written about him? He has lectured city planners, advertising men, TV executives, university professors, students, and scientists; business men have sought his message from a yacht in the Aegean Sea, a hotel in the Laurentians, a former firehouse in San Francisco, and in the board rooms of IBM, General Electric, and Bell Telephone. Although "a torrent of criticism" has been heaped upon him by ':' Research for this paper was undertaken while Prof. Gushue was at the .ontario Institute for Studies in Education during the 1967-68 acad emic year. A slightly modified version was delivered at the C.A.P.E. conference in Calgary, June, 1968. - Ed. 3 4 Marshall McLuhan the old dogies of academe and the literary establishment, he has been eulogized in dozens of scholarly magazines and studied serious ly by thousands of intellectuals.2 The best indication of his worth is the fact that among his followers are to be found people (artists, really) who are part of what Susan Sontag calls "the new sensibility." 3 They are, to use Louis Kronenberger's phrase, "the symbol manipulators," the peo ple who are calling the shots - painters, sculptors, publishers, pub lic relations men, architects, film-makers, musicians, designers, consultants, editors, T.V. -

Roth Book Notes--Mcluhan.Pdf

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Mediated America Part Two: Who Was Marshall McLuhan & What Did He Say? McLuhan, Marshall. The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (New York: Vanguard Press, 1951). McLuhan, Marshall and Bruce R. Powers. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989). McLuhan, Marshall. The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1962). McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994. Originally Published 1964). The Mechanical Bride: The Gutenberg Galaxy Understanding Media: The Folklore of Industrial Man by Marshall McLuhan Extensions of Man by Marshall by Marshall McLuhan McLuhan and Lewis H. Lapham Last week in Book Notes, we discussed Norman Mailer’s discovery in Superman Comes to the Supermarket of mediated America, that trifurcated world in which Americans live simultaneously in three realms, in three realities. One is based, more or less, in the physical world of nouns and verbs, which is to say people, other creatures, and things (objects) that either act or are acted upon. The second is a world of mental images lodged between people’s ears; and, third, and most importantly, the mediasphere. The mediascape is where the two worlds meet, filtering back and forth between each other sometimes in harmony but frequently in a dissonant clanging and clashing of competing images, of competing cultures, of competing realities. Two quick asides: First, it needs to be immediately said that Americans are not the first ever and certainly not the only 21st century denizens of multiple realities, as any glimpse of Japanese anime, Chinese Donghua, or British Cosplay Girls Facebook page will attest, but Americans first gave it full bloom with the “Hollywoodization,” the “Disneyfication” of just about anything, for when Mae West murmured, “Come up and see me some time,” she said more than she could have ever imagined. -

The Complexity of Richness: Media, Message, and Communication Outcomes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro The complexity of richness: Media, message, and communication outcomes By: Robert F. Otondo, James R. Van Scotter, David G. Allen, Prashant Palvia Otondo, R.F., Van Scotter, J.R., Allen, D.G., and Palvia, P. ―The Complexity of Richness: Media, Message, and Communication Outcomes.‖ Information & Management. Vol. 40, 2008, pp. 21-30. Made available courtesy of Elsevier: http://www.elsevier.com ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from Elsevier. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document.*** Abstract: Dynamic web-based multimedia communication has been increasingly used in organizations, necessitating a better understanding of how it affects their outcomes. We investigated factor structures and relationships involving media and information richness and communication outcomes using an experimental design. We found that these multimedia contexts were best explained by models with multiple fine-grained constructs rather than those based on one- or two-dimensions. Also, media richness theory poorly predicted relationships involving these constructs. Keywords: Media richness theory; Information richness; Communication theory Article: 1. Introduction Investigation of relationships between the media and communication effectiveness has not provided consistent results. However, lack of understanding has not deterred organizations from investing heavily in new and dynamic forms of web-based multimedia for their marketing, public relations, training, and recruiting activities. Few studies have examined the effects of media channels and informational content on decision-making and other organizational outcomes. -

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols

Copy Editing and Proofreading Symbols Symbol Meaning Example Delete Remove the end fitting. Close up The tolerances are with in the range. Delete and Close up Deltete and close up the gap. not Insert The box is inserted correctly. # # Space Theprocedure is incorrect. Transpose Remove the fitting end. / or lc Lower case The Engineer and manager agreed. Capitalize A representative of nasa was present. Capitalize first letter and GARRETT PRODUCTS are great. lower case remainder stet stet Let stand Remove the battery cables. ¶ New paragraph The box is full. The meeting will be on Thursday. no ¶ Remove paragraph break The meeting will be on Thursday. no All members must attend. Move to a new position All members attended who were new. Move left Remove the faulty part. Flush left Move left. Flush right Move right. Move right Remove the faulty part. Center Table 4-1 Raise 162 Lower 162 Superscript 162 Subscript 162 . Period Rewrite the procedure. Then complete the tasks. ‘ ‘ Apostrophe or single quote The companys policies were rewritten. ; Semicolon He left however, he returned later. ; Symbol Meaning Example Colon There were three items nuts, bolts, and screws. : : , Comma Apply pressure to the first second and third bolts. , , -| Hyphen A valuable byproduct was created. sp Spell out The info was incorrect. sp Abbreviate The part was twelve feet long. || or = Align Personnel Facilities Equipment __________ Underscore The part was listed under Electrical. Run in with previous line He rewrote the pages and went home. Em dash It was the beginning so I thought. En dash The value is 120 408. -

(1) Communication Process

Communication Process (1) The Communication Process Scholars have developed theories to Theories of how we explain how we communicate with each communicate: The other. Linear and Most of these theories are variations on Transactional two generally recognized models — the models Linear model and the Transactional model. Communication Process (2) Communication Process (3) This ancient cave First, let’s define what communication is. painting speaks to us across time through its Communication is symbolic human ability to symbolize. behavior systematized into written, In its representations of verbal, and nonverbal codes. the male figure, the bison, and the rhino, we Click here to learn more about this recognize a 40,000 ancient painting. year-old story of human experience — the hunt. 1 Communication Process (4) Communication Process (5) Symbols can tell us . When we systematize symbols, we create codes for communication. Here are different ways for symbolizing the letter “A.” . what to do. what not to do. where to get help. how to stay safe. Any person, place, thing, feeling, or idea can be symbolized. Communication Process (6) Communication Process (7) Now that you understand the symbolic nature Those who want to communicate must share the same symbol system. of communication, let’s return to the two models of communication mentioned earlier. A model is a representation used to show how individual parts work together to accomplish a specific purpose — in this case communication. 2 Linear Model of Linear Model of Communication (1) Communication (2) Linear model includes A source A message A channel Message Channel A receiver Views communication as a straight line, one The linear model is now way event, in which the process reverses Encodes regarded as being incomplete. -

Discourse Transcription

MNTA lBYABJMJB.A MPJEJB.S IN )LINGUISTICS VOLUrtlE 4: DISCOURSE TRANSCRIPTION JOHN W. DU BOIS, SUSANNA CUMMING STEPHAN SCHUETZE-COBURN, DANAE PAOLINO EDITORS DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA 199:2 Papers in Linguistics Linguistics Department University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California 93106-3100 U.S.A. Checks in U.S. dollars should be made out to UC Regents with $5.00 added for overseas postage. If your institution is interested in an exchange agreement, please write the above address for information. Volume 1: Korean: Papers and Discourse Date $13.00 Volume 2: Discourse and Grammar $10.00 Volume 3: Asian Discourse and Grammar $10.00 Volume 4: Discourse Transcription $15.00 Volume 5: East Asian Linguistics $15.00 Volume 6: Aspects of Nepali Grammar $15.00 Volume 7: Prosody, Grammar, and Discourse in Central Alaskan Yup'ik $15.00 Proceedings from the fIrst $20.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages Proceedings from the second $15.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages Proceedings from the third $15.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages Proceedings from the fourth $15.00 Workshop on American Indigenous Languages PART ONE: INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 What is discourse transcription? . 1.2 The goal of discourse transcription . 1.3 Options . 1.4 How to use this book . CHAPTER 2. A GOOD RECORDING 9 2.1 Naturalness . 2.2 Sound . 2.3 Videotape . CHAPTER 3. GETTING STARTED 12 3.1 How to start transcribing . 3.2 Delicacy: Broad or narrow? . 3.3 Delicacy conventions in this book . PART TWO: TRANSCRIPTION CONVENTIONS CHAPTER 4. -

Rethinking Media Richness: Towards a Theory of Media Synchronicity

Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 1999 Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 1999 Rethinking Media Richness: Towards a Theory of Media Synchronicity Alan R. Dennis Joseph S. Valacich Terry College of Business College of Business and Economics University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602 Washington State University, Pullman WA 99164 [email protected] [email protected] Abstract compensate for the weak findings and draw new This paper describes a new theory called a theory of conclusions based on the enhancements, or should we media synchronicity which proposes that a set of five attempt formulate a new theory [e.g., 34, 35, 41]? media capabilities are important to group work, and that In this paper, we take the second approach. We all tasks are composed of two fundamental communi- propose a new theory, which we call a theory of media cation processes (conveyance and convergence). synchronicity. The theory proposes that group Communication effectiveness is influenced by matching communication processes, regardless of task outcome the media capabilities to the needs of the fundamental objectives, are composed of two primary processes, communication processes, not aggregate collections of conveyance and convergence. The theory also proposes these processes (i.e., tasks) as proposed by media that media have a set of capabilities that play a dominant richness theory. The theory also proposes that the role when addressing each type of communication relationships between communication processes and process. Performance will be enhanced when media media capabilities will vary between established and capabilities are aligned with these processes. -

Bickerton, 2003. Symbol and Structure

SYMBOL AND STRUCTURE: A COMPREHENSIVE FRAMEWORK FOR LANGUAGE EVOLUTION Derek Bickerton Abstract. While an interdisciplinary approach is essential for the study of language evolution, linguistics must be assigned a key role. Many hypotheses plausible in terms of other disciplines are not consistent with basic facts about language. An overall framework is proposed that would dissociate the symbolic element of language (words) from the structural element (syntax), since the two probably have distinct sources. Syntax, though poorly understood by many non- linguists, is the likeliest Rubicon between ourselves and other species, but may not require quite so complex a neurological substrate as many have feared. Key words: evolution, linguistics, protolanguage, symbolism, syntax 1 1. Speaking as a linguist 1) . I approach the evolution of language as a linguist. This immediately puts me in a minority, and before proceeding further I think it’s worth pausing a moment to consider the sheer oddity of that fact. If a physicist found himself in a minority among those studying the evolution of matter, if a biologist found himself in a minority among those studying the evolution of sex, the world would be amazed, if not shocked and stunned. But a parallel situtation in the evolution of language causes not a hair to turn. Why is this? Several causes have contributed. Linguists long ago passed a self-denying ordinance that kept almost all of them out of the field, until quite recently. Since nature abhors a vacuum, and since the coming into existence of our most salient talent is a scientific question that should concern anyone seriously interested in why humans are as they are, other disciplines rushed to fill that vacuum. -

Słowo I Znak

Andrzej Bogusławski (Warszawa) Słowo i znak Summary The author claims that the word sign is not idiomatically applicable to linguistic expressions (apart from certain technical terms such as diacritic signs). Therefore, in the framework of postulated natural language idiomaticity of terminology, the following interrelations are to be considered incorrect: 1. identity of range of ‘lin- guistic expressions’ and ‘signs’, 2. inclusion of the latter in the former, 3. inclusion of the former in the latter, 4. intersection of the former and the latter. The correct relationship between the former and the latter is that of disjunction. On the other hand, there is a kind of analytic entailment between signs as the antecedent and linguistic expressions as a consequent: this is the fact that any idiomatic sign unilaterally involves the use of some linguistic expressions whereby the sign is introduced without the reverse of it being valid. In this perspective, any attempt at finding a generalization covering signs and linguistic expressions as placed on an equal footing, especially when the role of “common denominator” is assigned to ‘sign’, leads to absurdities (in particular, to a destructive infinite regress). The author closes his article with a commentary on the history of views con- cerning “signs” and their possible scopes as envisaged by different scholars. Streszczenie Autor twierdzi, że wyraz znak nie jest idiomatycznie stosowany do wyrażeń języko- wych (poza pewnymi terminami technicznymi, takimi jak znaki diakrytyczne). Dla- tego przy założeniu postulowanej naturalno-językowej idiomatyczności terminologii następujące relacje wypada uznać za błędne: 1. identyczność zakresu ‘wyrażeń językowych’ i ‘znaków’, 2. inkluzję tych ostatnich w tych pierwszych, 3. -

WRITING for ENGLISH COURSES Symbolism in Poetry

WRITING FOR ENGLISH COURSES Symbolism in Poetry A symbol is a person, object, place, event, or action that suggests more than its literal meaning. In poetry, symbols can be categorized as conventional, something that is generally recognized to represent a certain idea (i.e., a “rose” conventionally symbolizes romance, love, or beauty); in addition, symbols can be categorized as contextual or literary, something that goes beyond a traditional, public meaning (i.e., “night” conventionally symbolizes darkness, death, or grief; contextually it symbolizes other possibilities such as loneliness, isolation, fear, or emptiness). Whereas conventional symbols are used in poetry to convey tone and meaning, contextual or literary symbols reflect the internal state of mind of the speaker as revealed through the images. In order to have a better understanding of how poems are written, it is important to review the use of direct and indirect comparison. The literary term for a direct comparison is simile or a comparison with the words like, as, as if, or as though; the term for an indirect comparison is metaphor. Simile and metaphor are used to compare two things that are not similar and shows that they have something in common, as illustrated in the following examples: • Life is like a box of chocolates. This is a simile and suggests there are choices to make in life and one doesn’t always know what to expect from a decision. • Time is money. This is a metaphor and warns you that time is not infinite and whenever you expend time, you are making an investment that should be of value. -

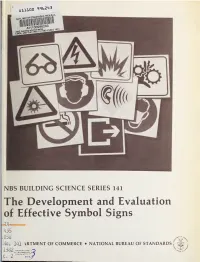

The Development and Evaluation of Effective Symbol Signs

NBS BUILDING SCIENCE SERIES 141 The Development and Evaluation of Effective Symbol Signs TA 435 .U58 NO, 141 ^RTMENT OF COMMERCE • NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS c. 2 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress on March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides: (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is per- formed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; develops, produces, and distributes Standard Reference -

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall Mcluhan: an Introduction

Chapter 1. “New Media” and Marshall McLuhan: An Introduction “Much of what McLuhan had to say makes a good deal more sense today than it did in 1964 because he was way ahead of his time.” - Okwor Nicholaas writing in the July 21, 2005 Daily Champion (Lagos, Nigeria) “I don't necessarily agree with everything I say." – Marshall McLuhan 1.1 Objectives of this Book The objective of this book is to develop an understanding of “new media” and their impact using the ideas and methodology of Marshall McLuhan, with whom I had the privilege of a six year collaboration. We want to understand how the “new media” are changing our world. We will also examine how the “new media” are impacting the traditional or older media that McLuhan (1964) studied in Understanding Media: Extensions of Man hereafter simply referred to simply as UM. In pursuing these objectives we hope to extend and update McLuhan’s life long analysis of media. One final objective is to give the reader a better understanding of McLuhan’s revolutionary body of work, which is often misunderstood and criticized because of a lack of understanding of exactly what McLuhan was trying to achieve through his work. Philip Marchand in an April 30, 2006 Toronto Star article unaware of my project nevertheless described my motivation for writing this book and the importance of McLuhan to understanding “new media”: Slowly but surely, McLuhan's star is rising. He's still not very respectable academically, but those wanting to understand the new technologies, from the iPod to the Internet, are going back to read what the master had to say about television and computers and the process of technological change in general.