Austria and China in Hofmannsthal and Kafka's Orientalist Fictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Anna Fröhlich]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0469/anna-fr%C3%B6hlich-330469.webp)

Anna Fröhlich]

Fröhlich, Anna dürften die vier Schwestern Fröhlich für die Kunst, na- mentlich für den Gesang, mehr gewirkt haben als so man- che Europa=berühmte Amazone von der Kehle, und wur- den in dankbarer Anerkennung ihrer regen Theilnahme, ihrer unermüdlichen Bestrebungen für diese classischen Concerte von allen Mitgliedern dieses Kunstvereines als die Stützen desselben betrachtet und bewundert.“ (“The participants [at the Kiesewetters’ house] were, as usual, professional musicians or exceptional amateur mu- sicians from the capital [Vienna]. The women’s choir – sopranos and altos – was made up of the more senior sin- ging students from the local conservatorium, directed by their teacher, Miss Nanette Fröhlich [Anna Fröhlich]. Re- cently, the solo parts have been entrusted to her private students or to her sister Josephine Fröhlich, who rise sparkling to the occasion every time. Indeed, the four Fröhlich sisters may have done more for art, and especial- ly for the art of song, than many a Europe-famous vocal Amazon, and were thankfully appreciated for their active participation, their tireless efforts for these classical con- Anna Fröhlich, Portrait von Emanuel Peter, 1830 certs, by all the members of this art society, who consider and admire them as the pillars of said society.”) Anna Fröhlich Birth name: Maria Anna Fröhlich („Aus Wien“ [Report on house concerts by Raphael Ge- org Kiesewetter]. In: Jahrbücher des Deutschen National- * 19 September 1793 in Wien, Österreich vereins für Musik und die Wissenschaft 4.1842, pp. † 11 March 1880 in Wien, Österreich 311-312, see also Waidelich 1997) The date of birth is unclear: both the 19th and the 30th Profile of November, 1793, have been named. -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Staging Memory: the Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 31 Issue 1 Austrian Literature: Gender, History, and Article 13 Memory 1-1-2007 Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek Gita Honegger Arizona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Honegger, Gita (2007) "Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 31: Iss. 1, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1653 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Staging Memory: The Drama Inside the Language of Elfriede Jelinek Abstract This essay focuses on Jelinek's problematic relationship to her native Austria, as it is reflected in some of her most recent plays: Ein Sportstück (A Piece About Sports), In den Alpen (In the Alps) and Das Werk (The Plant). Taking her acceptance speech for the 2004 Nobel Prize for Literature as a starting point, my essay explores Jelinek's unique approach to her native language, which carries both the burden of historic guilt and the challenge of a distinguished, if tortured literary legacy. Furthermore, I examine the performative force of her language. Jelinek's "Dramas" do not unfold in action and dialogue, rather, they are embedded in the grammar itself. -

I Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity Through the Oeuvre of Strauss And

Urban Opera: Navigating Modernity through the Oeuvre of Strauss and Hofmannsthal by Solveig M. Heinz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Germanic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Vanessa H. Agnew, Chair Associate Professor Naomi A. André Associate Professor Andreas Gailus Professor Julia C. Hell i For John ii Acknowledgements Writing this dissertation was an intensive journey. Many people have helped along the way. Vanessa Agnew was the most wonderful Doktormutter a graduate student could have. Her kindness, wit, and support were matched only by her knowledge, resourcefulness, and incisive critique. She took my work seriously, carefully reading and weighing everything I wrote. It was because of this that I knew my work and ideas were in good hands. Thank you Vannessa, for taking me on as a doctoral rookie, for our countless conversations, your smile during Skype sessions, coffee in Berlin, dinners in Ann Arbor, and the encouragement to make choices that felt right. Many thanks to my committee members, Naomi André, Andreas Gailus, and Julia Hell, who supported the decision to work with the challenging field of opera and gave me the necessary tools to succeed. Their open doors, email accounts, good mood, and guiding feedback made this process a joy. Mostly, I thank them for their faith that I would continue to work and explore as I wrote remotely. Not on my committee, but just as important was Hartmut. So many students have written countless praises of this man. I can only concur, he is simply the best. -

Im Nonnengarten : an Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott Aj Mes

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Resources Supplementary Information 1997 Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907 Michelle Stott aJ mes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation James, Michelle Stott, "Im Nonnengarten : An Anthology of German Women's Writing 1850-1907" (1997). Resources. 2. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophsupp_resources/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Supplementary Information at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Resources by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. lm N onnengarten An Anthology of German Women's Writing I850-I907 edited by MICHELLE STOTT and JOSEPH 0. BAKER WAVELAND PRESS, INC. Prospect Heights, Illinois For information about this book, write or call: Waveland Press, Inc. P.O. Box400 Prospect Heights, Illinois 60070 (847) 634-0081 Copyright © 1997 by Waveland Press ISBN 0-88133-963-6 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 765432 Contents Preface, vii Sources for further study, xv MALVIDA VON MEYSENBUG 1 Indisches Marchen MARIE VON EBNER-ESCHENBACH 13 Die Poesie des UnbewuBten ADA CHRISTEN 29 Echte Wiener BERTHA VON -

Prince Eugene and Maria Theresa: Gender, History, and Memory in Hofmannsthal in the First World War

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 31 Issue 1 Austrian Literature: Gender, History, and Article 2 Memory 1-1-2007 Prince Eugene and Maria Theresa: Gender, History, and Memory in Hofmannsthal in the First World War Wolfgang Nehring University of California Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Nehring, Wolfgang (2007) "Prince Eugene and Maria Theresa: Gender, History, and Memory in Hofmannsthal in the First World War ," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 31: Iss. 1, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1642 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Prince Eugene and Maria Theresa: Gender, History, and Memory in Hofmannsthal in the First World War Abstract Hugo von Hofmannsthal was one of the Austrian poets and intellectuals who took an active part in the historical-political events of 1914. He expected from the war a new vitality of public life and an end of the cultural crisis. In his early years he had advocated closer bonds between poesy and life. Now he encountered a situation that gave him the chance to strengthen his ties with reality. He worried about the existence of Austria, in which he was rooted, and tried to conjure up the Hapsburg spirit of the past for his contemporaries and to explain Austria's national history and right to exist to a large public. -

Heinrich Von Kleist

Heinrich von Kleist: Das gescheiterte Genie (Paper VIII, Paper X) Tue 2-3 (wks: 5-8), Taylor Institution Rm 2 This four-week lecture will cover the life and selected writings of Heinrich von Kleist. Besides the prescribed text for paper X, the play ‘Prinz Friedrich von Homburg’, the course will focus on the modernity and openness of Kleist’s work, making him up until the present day one of the most eminent authors in German language. His reputation becomes apparent in the continuous presence of his plays on German stages. While none of his works is autobiographic in a narrow sense, his narrative prose and his plays in many ways reflect the author’s personal struggle with emotions, sexuality and his failure ever to pursue a satisfactory career. To a certain extent, Kleist can be regarded as the contemporary counterpart to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the omnipotent embodiment of artistic genius. Finally, the lecture will address Kleist’s unabated relevance, exploring the ambiguities of justice and violence in texts like ‘Michael Kohlhaas’ and ‘die Hermannsschlacht’. This course will be held in German, which makes it particularly suitable for 2nd year students intending to spend their year abroad at a German university and for finalists who would like to improve their German language skills, in particular with relation to literature. To support language learning alongside the lecture’s literary subject matter, specific vocabulary will be addressed and the content will be recapitulated regularly throughout the lecture. Lecture plan: Week 5: Kleist: Leben – Themen – Rezeption Week 6: Widersprüche der Lektüre: Das Erdbeben in Chili Week 7: Die Geburt des Partisanen aus dem Geist der Poesie: Michael Kohlhaas / Die Hermannsschlacht Week 8: Traum und Wirklichkeit: Prinz Friedrich von Homburg Letters in German Literature: From Goethe's ‚’Werther’ to Kafka's 'Brief an den Vater' (Paper VIII, Paper X) Tue 9-10 (wks:1-8), 47 Wellington Square, Grnd Flr Lec Rm 1 This seminar will address the role of the letter in the history of German literature through selected examples. -

The German Classics of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-In-Chief: Kuno Francke

The German Classics of The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-in-Chief: Kuno Francke The German Classics of The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, Vol. VI. by Editor-in-Chief: Kuno Francke Produced by Stan Goodman, Jayam Subramanian and PG Distributed Proofreaders VOLUME VI HEINRICH HEINE FRANZ GRILLPARZER LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN THE GERMAN CLASSICS Masterpieces of German Literature TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH page 1 / 754 Patrons' Edition IN TWENTY VOLUMES ILLUSTRATED 1914 CONTRIBUTORS AND TRANSLATORS VOLUME VI CONTENTS OF VOLUME VI HEINRICH HEINE The Life of Heinrich Heine. By William Guild Howard Poems Dedication. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin page 2 / 754 Songs. Translators: Sir Theodore Martin, Charles Wharton Stork, T. Brooksbank A Lyrical Intermezzo. Translators: T. Brooksbank, Sir Theodore Martin, J.E. Wallis, Richard Garnett, Alma Strettell, Franklin Johnson, Charles G. Leland, Charles Wharton Stork Sonnets. Translators: T. Brooksbank, Edgar Alfred Bowring Poor Peter. Translated by Alma Strettell The Two Grenadiers. Translated by W.H. Furness Belshazzar. Translated by John Todhunter The Pilgrimage to Kevlaar. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin The Return Home. Translators: Sir Theodore Martin. Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker, James Thomson, Elizabeth Barrett Browning Twilight. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker page 3 / 754 Hail to the Sea. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker In the Harbor. Translated by Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker A New Spring. Translators: Kate Freiligrath-Kroeker, Charles Wharton Stork Abroad. Translated by Margaret Armour The Sphinx. Translated by Sir Theodore Martin Germany. Translated by Margaret Armour Enfant Perdu. Translated by Lord Houghton The Battlefield of Hastings. Translated by Margaret Armour The Asra. Translated by Margaret Armour The Passion Flower. -

Weekly Schedule

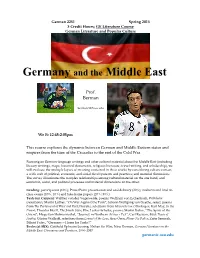

German 2251 Spring 2015 3 Credit Hours; GE Literature Course German Literature and Popular Culture and the Germany Middle East Prof. Berman [email protected] We Fr 12:45-2:05pm This course explores the dynamic between German and Middle Eastern states and empires from the time of the Crusades to the end of the Cold War. Focusing on German-language writings and other cultural material about the Middle East (including literary writings, maps, historical documents, religious literature, travel writing, and scholarship), we will evaluate the multiple layers of meaning contained in these works by considering culture contact; a wide web of political, economic, and social developments and practices; and material dimensions. The survey illuminates the complex relationships among cultural material on the one hand, and economic, social, and political processes and material dimensions on the other. Grading: participation (10%); PowerPoint presentation and oral delivery (20%); midterm and final in- class exams (10%, 10%) and take-home papers (20%; 30%). Texts (on Carmen): Walther von der Vogelweide, poems; Wolfram von Eschenbach, Willehalm (selections); Martin Luther, “On War Against the Turk”; Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, select. poems from The Parliament of West and East; Novalis, selections from Heinrich von Ofterdingen; Karl May, In the Desert; Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State; Else Lasker-Schüler, poems; Martin Buber, “The Spirit of the Orient”; Hugo von Hofmannsthal, “Journey in Northern Africa – Fez”; Carl Raswan, Black Tents of Arabia; Günter Wallraff, selections from Lowest of the Low; Aras Ören, Please No Police; Zafer Senocak, Bülent Tulay, “Germany—Home for Turks?” Books (at SBX): Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Nathan the Wise; Nina Berman, German Literature on the Middle East: Discourses and Practices, 1000-1989 germanic.osu.edu . -

Franz Werfel Papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt800007v5 No online items Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 Finding aid prepared by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 15 December 2017. Franz Werfel papers, 1910-1944 LSC.0512 1 LSC.0512 Title: Franz Werfel papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.0512 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 18.5 linear feet(37 boxes and 1 oversize box) Date: 1910-1944 Abstract: Franz Werfel (1890-1945) was one of the founders of the expressionist movement in German literature. In 1940, he fled the Nazis and settled in the U.S. He wrote one of his most popular novels, Song of Bernadette, in 1941. The collection consists of materials found in Werfel's study at the time of his death. Includes correspondence, manuscripts, clippings and printed materials, pictures, artifacts, periodicals, and books. Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance through our electronic paging system using the request button located on this page. Werfel's desk on permanent loan to the Villa Aurora in Pacific Palisades. Creator: Werfel, Franz, 1890-1945 Conditions Governing Reproduction and Use Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. -

Fall, 2012 GER 382M: Court, City, Nation: Transformations Of

Fall, 2012 GER 382M: Court, City, Nation: Transformations of Europe (unique # 38085) Instructor: Katherine Arens Office Hrs: TTH 9-10:45 & by appointment Office: BUR 320 232-6363 Germanic Languages [email protected] Class: TTH 11-12:30 BUR 232 This course will follow Norbert Elias’ Court Society, Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction, and Michel de Certeau’s Mystic Fable to investigate the shift in history and in human consciousness that happened in Europe between approximately 1770 and 1830. This era saw the end of Absolutism, the French Revolution, Napoleon’s conquests, and the Restoration after the Congress of Vienna. This course uses this era of crisis to set up a number of case studies in "German" cultural history, to explore the various ways in which historical shifts can cause changes in both individual and cultural consciousness. The first case study is one in representational consciousness: using Peter Burke’s book on Louis XIV as a starting point, we will outline what constituted personal and national identity under absolutism and in “court style.” The most familiar cultural texts here are Mozart’s Zauberflöte and Goethe’s Götz von Berlichingen. The second case study is one in political consciousness: using Black Bread, White Bread (on Germany’s reaction to the French Revolution), we will trace the formation of reactions to the French Revolution in works by three generations of authors, from Wieland through Büchner. The third case study focuses on cultural consciousness. Given the continental blockade and other political disruptions of the Napoleanic era, the countries of Europe were forced to reevaluate their cultural identities. -

Abendlicher Reigen Georg Trakl ...306 Abends

Abendlicher Reigen Georg Trakl ....................................... 306 Abends/Auf meinem Schoße sitzet nun Theodor Storni ... 270 Abenteuer Eva Strittmatter................................................. 26 Abschiedsworte an Pellka Joachim Ringelnatz .................. 173 Ach Robert Gemhardt ......................................................... 31 Ach Liebste, laß uns eilen Martin Opitz ............................. 14 Ach, noch in der letzten Stunde Robert Gernhardt .............. 31 Ach, sie strampelt mit den Füßen Frank Wedekind .......... 275 Advent Werner Finck ........................................................ 343 Advent Mascha Kaliko ...................................................... 344 Albumblatt Franz Grillparzer ............................................. 86 Alleine saß das Nashorn da Bernd Pfarr ........................... 226 Alles kann sich umgestalten! Friedrich von Matthisson ... 150 Als ich ihn erwartete Sophie Albrecht................................. 134 Als ich zum ersten Mal die Sanfte sah Robert W alser........268 Als sie einander acht Jahre kannten Erich Kästner ............ 300 Als Zeus Europen lieb gewann Gotthold Ephraim Lessing 132 Am Brunnen Thomas Bernhard ........................................... 35 Amara (Pidgin) Hans Magnus Enzensberger ..................... 98 Amara, bittre, was du thust ist bitterFriedrich Rückert ... 97 Amara, du nix gut Hans Magnus Enzensberger .................. 98 An des Dichters andere Hälfte, den Leser Christian Morgenstern.......................................................