Coastal Fishing Communities in Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on Health Tourism Management for Middle Eastern Tourists in Phuket Province

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Computer Science 65 ( 2015 ) 1146 – 1153 International Conference on Communication, Management and Information Technology (ICCMIT 2015) Guidelines on Health Tourism Management for Middle Eastern Tourists in Phuket Province Oraphan Chanina, Ploykanok Khunchumnana, Suwapas Amphansookkoa, Kulteera Thongyaia, Jutamas Rodneuma, Piangpis Sriprasertb aRajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya, Songkla, 90000, Thailand bNakorn Si Thammarat Rajabhat Univerisity, Nakorn Si Thammarat, 80000, Thailand Abstract There are three objectives in this study, 1) to study the behaviour and needs of Middle Eastern tourists for health tourism, 2) to study elements of health tourism for Middle Eastern tourists, and 3) to study guidelines on health tourism management for Middle Eastern tourists. The sample in this study is 400 Middle Eastern tourists, and 10 government staff. The research tools used were questionnaires and interviews. The study found that the Middle Eastern tourists have high needs in health tourism which are as follows: 1) fair prices 2) embedding intensity 3) aromatherapy IP terminals 4) souvenirs for home, and 5) public transportation. Following the average analysis (t- test), it revealed that these aspects have a statistical difference of 0.05 between the sexes with regard to health tourism. Moreover, seven aspects that have a significant statistical difference at 0.05 were age, education, income, occupation, status, experience and nationality with regards to health tourism. According to the study, indicators which were claimed to assist in managing health tourism include; 1) variety of activities 2) Islam friendly accommodation 3) public transport 4) promotion of health tourism 5) access to prayer rooms 6) access to health tourism information, and 7) fair price of souvenirs. -

Zootaxa,Namtokocoris Sites, a New Genus of Naucoridae

Zootaxa 1588: 1–29 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Namtokocoris Sites, a new genus of Naucoridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) in waterfalls of Indochina, with descriptions of six new species ROBERT W. SITES AND AKEKAWAT VITHEEPRADIT Enns Entomology Museum, Division of Plant Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri 65211, USA Abstract A new genus with six new species of Naucoridae inhabiting waterfalls of Indochina are described from a decade of aquatic insect collections in Thailand and Vietnam. Namtokocoris Sites NEW GENUS is diagnosed by a pair of promi- nent scutellar protuberances, the prosternal midline bears an expansive, thin, plate-like carina, the forelegs of both sexes have a one-segmented tarsus apparently fused with the tibia, and a single claw. Prominent linear series of stout hairs occur on the hemelytra, although this attribute is not unique within the subfamily. Despite the lack of sexual dimorphism in the forelegs, this new genus is a member of the subfamily Laccocorinae, an assignment based on other characters con- sistent with this subfamily. Character states of this genus are compared with those of other Asian genera of Laccocori- nae. The type species, Namtokocoris siamensis Sites NEW SPECIES, is widely distributed from northern through eastern Thailand in waterfalls of several mountain ranges. Namtokocoris khlonglan Sites NEW SPECIES was collected only at Namtok Khlong Lan at Khlong Lan National Park. Namtokocoris minor Sites NEW SPECIES was collected at two waterfalls near the border with Burma in Kanchanaburi Province and is the smallest species known. -

National Report for Seagrass in Cambodia

United Nations UNEP/GEF South China Sea Global Environment Environment Programme Project Facility NATIONAL REPORT on Seagrass in the South China Sea THAILAND Dr. Suvaluck Satumanatpan Focal Point for Seagrass Faculty of Environment and Resource Studies Mahidol University, Salaya Campus Nakorn Pathom 73170, Thailand NATIONAL REPORT ON SEAGRASS IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA – THAILAND Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 2. REVIEW OF NATIONAL DATA AND INFORMATION....................................................................1 2.1 GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION .......................................................................................................1 2.2 PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL CHARACTERISTICS...............................................................................1 2.3 BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS.................................................................................................................2 2.3.1 Seagrass ........................................................................................................................2 2.3.2 Associated Marine Biota ................................................................................................3 2.3.3 Dugong...........................................................................................................................5 2.4 THREATS TO SEAGRASS .............................................................................................................6 -

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

OF POLLUTANT-INDUCED CHANGES in Bangkok, 1995

REGIONAL COORDINATING UNIT EAST ASIAN SEAS ACTION PLAN UNEP UNITED NATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORKSHOP ON SOFT-BOTTOM BENTHIC COMMUNITIES AS INDICATORS OF POLLUTANT-INDUCED CHANGES IN THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT Edited by L.M. Chou RCU/EAS TECHNICAL REPORTS SERIES NO. 7 Prepared in cooperation with: NU S UNEP Bangkok, 1995 Note: This document is proceedings of the Workshop on Soft-bottom Benthic Communities as Indicators of Pollutant-induced Changes in the Marine Environment. The workshop was organized and convened during 20-29 March 1995 by the Department of Zoology of National University of Singapore (NUS) as one of the activities under the EAS-33 project "FP/ESI9101-94-66: Training workshop on the biological effects of pollutants: East Asian Seas region." This volume is published under the Regional Coordinating Unit for the East Asian Seas Action Plan's (EAS/RCU) Technical Report Series. These series are based on the selected reports that are the result of various activities approved by the COBSEA and implemented within the frameworks of the Action Plan for the Protection and Sustainable Development of Marine and Coastal Areas of the East Asian Region. The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any State, Territory, city or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The document contains the views expressed by the authors acting in their individual capacities, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNEP or NUS. -

Do You Want to Travel Different? 50 Great Great 50 Green Escapes Green Become a Green Traveller Today

THAILAND DO YOU WANT TO TRAVEL DIFFERENT? 50 GREAT GREEN ESCAPES BECOME A GREEN TRAVELLER TODAY By visiting the destinations highlighted in this guidebook, and by reporting your impressions and comments to www.tourismthailand.org/7greens you will help the Tourism Authority of Thailand promote and preserve the country’s natural wonders. THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT. Become a Green Traveller Today Tourism Authority of Thailand Published and distributed by Tourism Authority of Thailand Attractions Promotion Division Product Promotion Department. Editor: Richard Werly / AsieInfo Ltd, ITF Silom Palace, 163/658 Silom Road, Bangkok 10500. Producer: Titaya Jenny Nilrungsee Assistant editor: Thanutvorn Jaturongkavanich Assistant producer: Janepoom Chetuphon Design & Artwork: Tistaya Nakneam Writer: Chandra Hope Heartland Special Thanks: Simon Bowring, TAT Photo Bank, Solomon Kane Copyright © 2010 Tourism Authority of Thailand. Thailand Tourism Awards (www.tourismthailand.org/tourismawards) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from Tourism Authority of Thailand. ISBN: 978-974-679-200-4 Printed in Thailand by Amarin Printing and Publishing Public Company Limited. Seven The production of this book was done in strict compliance with forward thinking environmental the initiatives from the team. It was created using recyclable environmentally -

26178938.Pdf

Thappud Sarasin Bridge Khao Lak Ao Luk Yacht haven Marina Thepkassatri Road Andanman Sea Water Village Kok Kloi James Bond Island Sak Cape Khao Phanom Mai Khao Phang-Nga Bay Beach Phuket Int’l Airport National Park Khao Phanom Benja National Park Koh Hong Thai Rat Cape Sirinath Huay To Waterfall National Park Blue Canyon Kung Bay Koh Panak Nai Yang Beach Mission Hills d a Sai Cape o R i r Helipad t a s Ao Po Grand Marina s a Koh Yao Noi k Koh Reat p e Krabi Airport h T Naithon Beach Kho Phra Taew National Park Po Bay Thalang Bang Pae Waterfall Krabi City Nua Klaong Koh kala Ton Sai Waterfall Layan Phuket T h Layan Beach e Airpark p Bang Rong Bay k a s s Koh Yao Yai a Klong Thom t Ao Pranang ri R o a Paklok Bang Tao Beach Laguna d Phuket Koh Poda Heroines' Son Cape Monument Yamu Cape Island Koh Kai Cherngtalay Srisoonthorn Road Surin Beach Sing Cape Tha Ruea Boat Lagoon Marina Koh Si Bo Ya Royal Phuket Marina Kamala Beach Koh Rang Yai Tha Ruea Bay Hua Lan Cape Hin Koh Yung d Koh Phai a Cape o Koh Maphrao R Kathu Waterfall s s Loch Palm a P y Koh Pu B Sapam Tourist Thepkassatri Road Police Kalim Beach d Kathu Ph oa ra Baramee R Koh Phi Phi Don Patong Beach Phuket Country Club Homeworks Koh Koh Phi Phi Le Bang Wad Dam Phuket Sire King Rama Freedom Bay IX Park City Copyright Ltd 2004© Image Co Events Asia Sakdidej Kwang VichitRd. -

Suggestions for the Development of Thai Music in Entertainment Venues to Promote Tourism in Phuket

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 6, No. 2; 2014 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Suggestions for the Development of Thai Music in Entertainment Venues to Promote Tourism in Phuket Teerathorn Lamnaokrut1,3, Songkoon Chantachon1 & Marisa Koseyayothin2 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand 2 Kanchanapisek Non-Formal Education Centre (Royal Academy), Salaya Sub-District, Bhuttamonthon District, Nakhon Pathom Province, Thailand 3 Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus, Amphur Kathu, Phuket, Thailand Correspondence: Teerathorn Lamnaokrut, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 29, 2014 Accepted: May 29, 2014 Online Published: June 12, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v6n2p139 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v6n2p139 Abstract This qualitative research uses observation, interview and focus group discussion to study the background and problems of Thai music ensembles in Phuket, so to make suggestions for their development. The research findings reveal that since the city shifted from tin-mining to tourism, Thai music has been used to welcome tourists. There are three problems in the Thai music business: a) problems with Thai music troupes; b) problems with places where Thai music is performed; and c) problems with tourists. The main cause of the problems is a lack of effective cooperation between Thai music ensembles and their employers. The research makes five suggestions for musical adaptations: 1) Thai music and folk music, 2) Thai and Western music, 3) Thai music and sounds, 4) Thai music and performances, and 5) music from CDs and performances. -

UNHCR/UNIFEM/UNOHCHR/WB Joint Tsunami Migrant Assistance

TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE MISSION REPORT IOM/ UNHCR/UNIFEM/UNOHCHR/WB Joint Tsunami Migrant Assistance Mission to the Provinces of Krabi, Phangnga, Phuket and Ranong, Thailand 20-25 January 2005 Date of publication: 16 February 2005 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary............................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations.......................................................................................... 5 Map of Affected Areas........................................................................................................ 6 I. Size and location of the Tsunami-Affected Migrant Population ............................ 7 a) Total number of migrants in four provinces ....................................................... 7 b) Phangnga Province.............................................................................................. 8 c) Ranong Province............................................................................................... 10 d) Phuket Province ................................................................................................ 11 e) Krabi Province .................................................................................................. 11 II. Effect of Tsunami on Migrant Workers................................................................ 13 a) Death Toll and Injuries -

Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don

SEI - Africa Institute of Resource Assessment University of Dar es Salaam P. O. Box 35097, Dar es Salaam Tanzania Tel: +255-(0)766079061 SEI - Asia 15th Floor, Witthyakit Building 254 Chulalongkorn University Chulalongkorn Soi 64 Phyathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel+(66) 22514415 Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report - 2009 SEI - Oxford Suite 193 266 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7DL UK Tel+44 1865 426316 SEI - Stockholm Kräftriket 2B SE -106 91 Stockholm Sweden Tel+46 8 674 7070 SEI - Tallinn Lai 34, Box 160 EE-10502, Tallinn Estonia Tel+372 6 276 100 SEI - U.S. 11 Curtis Avenue Somerville, MA 02144 USA Tel+1 617 627-3786 SEI - York University of York Heslington York YO10 5DD UK Tel+44 1904 43 2897 The Stockholm Environment Institute Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for SEI is an independent, international research institute.It has been Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don engaged in environment and development issuesat local, national, regional and global policy levels for more than a quarterofacentury. Emma Calgaro, Sopon Naruchaikusol, and Kannapa Pongponrat SEI supports decision making for sustainable development by bridging science and policy. sei-international.org Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don Sustainable Recovery and Resilience Building in the Tsunami Affected Region Emma Calgaro, Sopon Naruchaikusol, and Kannapa Pongponrat (1) Department of Environment and Geography, Macquarie University, Sydney (2) Stockholm Environment Institute -

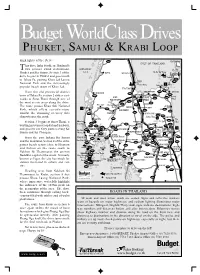

Phuket &Krabi Loop

Budget WorldClass Drives PHUKET, SAMUI & KRABI LOOP Highlights of the Drive 4006 KO PHANGAN G U L F O F T H A I L A N D his drive links Southern Thailand’s T two premier island destinations, A N D A M A N Ban Chaweng Mu Ko Ang Thong Phuket and Ko Samui. Section 1 of the S E A KAPOE THA CHANA KO SAMUI drive begins in Phuket and goes north Ban Nathon to Takua Pa, passing Khao Lak Lamru 4169 CHAIYA 4170 National Park and the increasingly Phum Riang 4 Ferry popular beach resort of Khao Lak. DON SAK THA CHANG 4142 From the old provincial district KANCHANADIT 4142 KHANOM KURA BURI 41 PHUNPHIN 4232 town of Takua Pa, section 2 strikes east- 4 401 4014 Hat Nai KHIRI SURAT 4010 wards to Surat Thani through one of RATTANIKHOM THANI Phlao 401 3 the most scenic areas along the drive. 4134 4100 Khao Sok Rachaphrapha 41 The route passes Khao Sok National KHIAN SA SICHON TAKUA PA Dam SAN NA DOEM 2 401 4106 Park, which offers eco-adventure BAN TAKHUN 4009 401 4133 amidst the stunning scenery that 4032 PHANOM BAN NA SAN 4188 4186 characterises the park. Krung Ching NOPPHITAM KAPONG 415 4140 THA Khao Lak WIANG SA (roads closed) SALA Section 3 begins at Surat Thani, a 4090 Lam Ru 4035 PHRA PHIPUN 4141 bustling provincial capital and harbour, 4240 4090 PHLAI PHRAYA 4016 4 4197 SAENG PHROMKHIRI 4013 4133 4015 5 and goes to car-ferry ports serving Ko 4 PHANG NGA 4035 CHAI BURI NAKHON SRI Hat Thai THAP PHUT 4228 Khao Samui and Ko Phangan. -

Sedimentary Characteristics of Sand Dune from Bang Berd, Chumphon Province, Southern Thailand

28 Sedimentary characteristics of sand dune from Bang Berd, Chumphon Province, Southern Thailand Nattawut Prachantasen1, Montri Choowong2*, Santi Pailoplee2 and Sumet Phantuwongraj2 1 International Logging Overseas Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand 2 Department of Geology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand * Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract The stratigraphy and sedimentary structures within Bang Berd dune field suggest a geological history that includes paleo-storm deposits. The goal of this project is to characterize the sand dunes in terms of their sedimentological features, including grain size distribution, internal sedimentary structures, wind direction indicators and documenting the evidence for paleo-storm deposits in this area. On aerial photographs, the dunes are aligned in N- W and S-E wind directions. Sand dunes here can be divided, on the basis of their geographic position and their morphological features into 3 units, outer dunes, middle dunes and inner dunes. Interestingly, sedimentary structures within the sand dune are very rare; only well developed inclined lamination can distinguish washover deposits from dune deposits. Both wind-blown and washover sands are very fine-grained, well to very well sorted and subrounded to rounded. The deposition of washover deposits that cover the outer dunes that is aligned in an almost east-west direction may indicate unusual paleo-storm pathways strike into the areas based on alternated washover deposits and dune sequence during 93+18 and 126+14 years ago. Key words: sand dune, washover, OSL, Bang Berd 1. INTRODUCTION Sand dunes occur in many environments, including along sea coasts, lake shores and desert. The direction and velocity of wind, in addition to the local supply of sand, result in a variety of dune shapes and sizes (Fritz and Moore., 1987).