5 I. Introduction 17 II. Executive Summary / Kurzfassung / 19 Synthèse Des Résultats De L'étude III. European Summary 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Food Affair – a Study on Interventions to Stimulate Positive Consumption Behavior

A Food Affair – A Study on Interventions to Stimulate Positive Consumption Behavior Katrien Cooremans 2018 Advisors: Prof. Dr. Maggie Geuens, Prof. Dr. Mario Pandelaere Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Ghent University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Business Economics ii DOCTORAL JURY Dean Prof. Dr. Patrick Van Kenhove (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Maggie Geuens (Ghent University & Vlerick Business School) Prof. Dr. Mario Pandelaere (Virginia Tech & Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Anneleen Van Kerckhove (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Hendrik Slabbinck (Ghent University) Prof. Dr. Erica van Herpen (Wageningen University) Prof. Dr. Robert Mai (Grenoble Ecole de Management) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am truly grateful to my promotor, Maggie Geuens, who took a chance on me and gave me the opportunity to start working at the department of Marketing and to my co-promotor Mario Pandelaere, who took me on in a time of ‘financial’ crisis. I am especially grateful for their belief in me throughout this entire journey. I might not be your average PhD researcher, but they always gave me the space and confidence to follow my interests and pursue my ideas. I am grateful to the members of the exam committee for their insightful comments and for the questions they raised. These will certainly benefit my (hopefully) forthcoming papers and I already believe they brought them to a higher level. I feel very grateful for my colleagues and ex-colleagues for making our department such an amazzzing place to work at. And especially my office mates for always being able to turn my frown upside down. -

Is There a World Beyond Supermarkets? Bought These from My Local Farmers’ My Local Box Market Scheme Delivers This I Grew These Myself!

www.ethicalconsumer.org EC178 May/June 2019 £4.25 Is there a world beyond supermarkets? Bought these from my local farmers’ My local box market scheme delivers this I grew these myself! Special product guide to supermarkets PLUS: Guides to Cat & dog food, Cooking oil, Paint feelgood windows Enjoy the comfort and energy efficiency of triple glazed timber windows and doors ® Options to suit all budgets Friendly personal service and technical support from the low energy and Passivhaus experts www.greenbuildingstore.co.uk t: 01484 461705 g b s windows ad 91x137mm Ethical C dec 2018 FINAL.indd 1 14/12/2018 10:42 CAPITAL AT RISK. INVESTMENTS ARE LONG TERM AND MAY NOT BE READILY REALISABLE. ABUNDANCE IS AUTHORISED AND REGULATED BY THE FINANCIAL CONDUCT AUTHORITY (525432). add to your without arming rainy day fund dictators abundance investment make good money abundanceinvestment.com Editorial ethicalconsumer.org MAY/JUNE 2019 Josie Wexler Editor This is a readers choice issue – we ask readers to do ethical lifestyle training. We encourage organisations and an online survey each Autumn on what they’d like us networks focussed on environmental or social justice to cover. It therefore contains guides to some pretty issues to send a representative. disparate products – supermarkets, cooking oil, pet food and paint. There is also going to be a new guide to rice Our 30th birthday going up on the web later this month. As we mentioned in the last issue, it was Ethical Animal welfare is a big theme in both supermarkets and Consumer’s 30th birthday in March this year. -

Internet Nondiscrimination Principles: Commercial Ethics for Carriers and Search Engines

5/4/2008 5:24:10 PM Internet Nondiscrimination Principles: Commercial Ethics for Carriers and Search Engines Frank Pasquale† I. INTRODUCTION Dominant search engines (“DSEs”)1 are becoming a hub of convergence culture.2 They provide an ever-expanding array of services.3 As they amass information about their users, calls for † Professor of Law, Seton Hall Law School; Associate Director of the Gibbons Insti- tute of Law, Science, and Technology, Seton Hall University. I wish to thank the Univer- sity of Chicago Legal Forum for asking me to present this article. Marina Lao, Ellen Goodman, James Grimmelmann, Danielle Citron, and Brett Frischmann offered very insightful comments. 1 We can provisionally define a dominant search engine (DSE) as one with over 30 percent market share. Google clearly satisfies this criterion in the U.S. and much of Eu- rope. See Steve Lohr, As its Stock Tops $600, Google Faces Growing Risks, NY Times C1 (Oct 13, 2007) (remarking that “[i]n September, Google’s share of Web searches in the United States was 67 percent, up from 54 percent a year earlier, reports Compete.com, a Web analytics firm. The Yahoo share was 19 percent, compared with 29 percent a year earlier. And Microsoft had 9 percent, up slightly from a year ago.”). But Google would not qualify as a DSE in South Korea, where Naver dominates. See, for example, Choe Sang- Hun, South Koreans Connect Through Search Engine, NY Times (July 5, 2007), available at <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/05/technology/05online.html?ref=technology> (last visited Mar 28, 2008) (noting that “[w]eb users in one of the world’s most-wired countries seldom “Google” anything. -

Incentives, Demographics, and Biases of Ethical Consumption: Observation of Modern Ethical Consumers

Incentives, Demographics, and Biases of Ethical Consumption: Observation of Modern Ethical Consumers Laura Kim University of California, Berkeley B.A. of Economics and Statistics Thesis Advisor J. Bradford DeLong Special Thanks to Professor Demian Pouzo, Professor Kyong Shik Eom Abstract This paper seeks to offer a better understanding of modern consumers’ incentives, intentions and behavior regarding “ethical consumption”. Using likelihood treatment models, we find that both the likelihood and increase in ethical consumption is less contingent on income but rather on the amount of entire purchase of consumers. Increase in year of education has significant positive effect on ethical consumption, particularly to female consumers. Racial and regional characteristics are not significant predictors of ethical consumption. Purchase of ethical products are also influenced by internal motivation of consumers defined as ‘identifying incentive,’ which in turn depends on various factors that influence consumption. This paper argues that because of the heightened importance of the consumers’ decision making, not only should we explore the decision making of the consumers but also enlarge the scope of knowledge of such consumers of their incentives, demographics, and biases regarding altruistic consumption. Engaging with extensive literature on consumer behavior, this paper uses the Nielsen data and datasets from Label Insight to discover pieces of information that helps us identify factors that contribute to someone’s ethical purchase. Keywords: ethical consumption, consumerism, social responsibility, consumer behavior 1. Introduction The standard economic model essentially suggests that consumers will be consistently rational, utility maximizing, and self-interested upon decision making. Rational and self-interested economic agents from our model is expected to make rational choices that give them the most utility per dollar spent by maximizing their consumption bundles with respect to their budget constraints. -

Ethical Consumer, Issue 172, May/June 2018

www.ethicalconsumer.org EC172 May/June 2018 £4.25 Can you see where your money goes? We rank finance companies on their transparency Product guides to: Current Accounts Savings Accounts App Banks Ethical Pensions Home & Car Insurance Ethical Investment Funds Plus: Company responses to the Modern Slavery Act Contents ethicalconsumer.org MAY/JUNE 2018 who’s who p4 product guides this Issue’s editors Rob Harrison, Jane Turner, Josie Wexler finance special proofing Ciara Maginness (littlebluepencil.co.uk) 15 directors’ pay writers/researchers Jane Turner, Tim Hunt, Leonie Nimmo, Rob Harrison, Heather Webb, Anna Clayton, 16 BankTrack Joanna Long, Josie Wexler, Ruth Strange, Mackenzie Denyer, Clare Carlile, Francesca de la Torre 17 Save Our Bank regular contributors Simon Birch, Bryony Moore, 24 Banking on Climate Change Shaun Fensom, Colin Birch design and layout Adele Armistead (Moonloft), Jane 25 Don’t Bank on the Bomb Turner 43 crowdfunding cover © Anon Luengwanichprapa | Dreamstime.com cartoons Marc Roberts, Andy Vine, Richard Liptrot current accounts ad sales Simon Birch 10 introduction subscriptions Elizabeth Chater, Francesca Thomas p54 press enquiries Simon Birch, Tim Hunt 12 score table & Best Buys enquiries Heather Webb web editor Georgina Rawes thanks also to Eleanor Boyce, Ashraf Hamad, Josh savings accounts Wittingham, Jess Aurie 18 building societies All material correct one month before cover date and © 19 cash ISAs Ethical Consumer Research Association Ltd. ISSN 0955 8608. 20 score table & Best Buys 23 credit unions Printed with vegetable ink by RAP Spiderweb Ltd, c/o the Commercial Centre, Clowes Centre, Hollinwood, Oldham OL9 7LY. 0161 947 3700. app banking Paper: 100% post-consumer waste, chlorine-free and 26 score table & Best Buys sourced from the only UK paper merchant supplying only recycled papers – Paperback (www.paperbackpaper.co.uk). -

Can Consumer Demand Deliver Sustainable Food?

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Anthropology Faculty Scholarship Anthropology 2012 Can Consumer Demand Deliver Sustainable Food?: Recent Research in Sustainable Consumption Policy & Practice Cindy Isenhour University of Maine, Department of Anthropology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ant_facpub Part of the Agriculture Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, and the Public Economics Commons Repository Citation Isenhour, Cindy. 2012. Can Consumer Demand Deliver Sustainable Food?: Recent Research in Sustainable Consumption Policy & Practice. Environment & Society 2(1): 5-28. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isenhour, Cindy. 2012. Can Consumer Demand Deliver Sustainable Food?: Recent Research in Sustainable Consumption Policy & Practice. Environment & Society 2(1): 5-28. Introduction Food has always played a central, mediating role in the relationship between humans and our environments. Anthropologists and historians, among others, have long illustrated how subsistence systems have helped to shape our societies, linking people and our views of the world to localized experiences of gathering, preparing and consuming food. Yet today, in the context of an increasingly standardized and industrial global food system, the separation of food as a social product from the economic and natural systems that produce it has inspired significant protest (Walter 2008, Wilk 2006). Food activists have contested the conditions that alienate us, physically and emotionally, from the human and natural systems that generate our sustenance, lamented the loss of control over our food supply, and advocated a return to safe, sustainable and healthy foods. -

Transcript 061106.Pdf (393.64

1 1 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION 2 3 I N D E X 4 5 6 WELCOMING REMARKS PAGE 7 MS. HARRINGTON 3 8 CHAIRMAN MAJORAS 5 9 10 PANEL/PRESENTATION NUMBER PAGE 11 1 19 12 2 70 13 3 153 14 4 203 15 5 254 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 For The Record, Inc. (301) 870-8025 - www.ftrinc.net - (800) 921-5555 2 1 FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION 2 3 4 IN RE: ) 5 PROTECTING CONSUMERS ) 6 IN THE NEXT TECH-ADE ) Matter No. 7 ) P064101 8 ) 9 ---------------------------------) 10 11 MONDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 2006 12 13 14 GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY 15 LISNER AUDITORIUM 16 730 21st Street, N.W. 17 Washington, D.C. 18 19 20 The above-entitled workshop commenced, 21 pursuant to notice, at 9:00 a.m., reported by Debra L. 22 Maheux. 23 24 25 For The Record, Inc. (301) 870-8025 - www.ftrinc.net - (800) 921-5555 3 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 - - - - - 3 MS. HARRINGTON: Good morning, and welcome to 4 Protecting Consumers in The Next Tech-Ade. It's my 5 privilege to introduce our Chairman, Deborah Platt 6 Majoras, who is leading the Federal Trade Commission 7 into the next Tech-ade. She has been incredibly 8 supportive of all of the efforts to make these hearings 9 happen, and I'm just very proud that she's our boss, and 10 I'm very happy to introduce her to kick things off. 11 Thank you. 12 CHAIRMAN MAJORAS: Thank you very much, and good 13 morning, everyone. -

Ethical Consumers and Ethical Trade: a Review of Current Literature (NRI Policy Series 12)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive Ethical consumers and ethical trade: a review of current literature (NRI Policy Series 12) Greenwich Academic Literature Archive (GALA) Citation: Tallontire, Anne, Rentsendorj, Erdenechimeg and Blowfield, Mick (2001) Ethical consumers and ethical trade: a review of current literature (NRI Policy Series 12). [Working Paper] Available at: http://gala.gre.ac.uk/11125 Copyright Status: Permission is granted by the Natural Resources Institute (NRI), University of Greenwich for the copying, distribution and/or transmitting of this work under the conditions that it is attributed in the manner specified by the author or licensor and it is not used for commercial purposes. However you may not alter, transform or build upon this work. Please note that any of the aforementioned conditions can be waived with permission from the NRI. Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by this license. This license in no way affects your fair dealing or fair use rights, or other applicable copyright exemptions and limitations and neither does it affect the author’s moral rights or the rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. For any reuse or distribution, you must make it clear to others the license terms of this work. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. -

Fair Trade Website Content: Effects of Information Type and Emotional Appeal Type

Fair Trade Website Content: Effects of Information Type and Emotional Appeal Type Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Songyee Hur Graduate Program in Fashion and Retail Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Leslie Stoel, Adviser Robert Scharff Soobin Seo Copyrighted by Songyee Hur 2014 Abstract The primary objective of current research was to explore the impacts of information type and emotional appeal type for fair trade store information presented in the online shopping environment. The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model forms the foundation for investigating the relationships among environmental stimuli (information type and emotional appeal type), consumer cognitive response (perceptions of information quality), affective response (feelings of pleasure, arousal), and behavioral response (purchase intention). The design of the proposed model was a 2 information type (concrete vs. abstract) X 2 emotional appeal type (happiness vs. sadness) between-subjects experiment. Dependent variables were information quality, pleasure, arousal, and purchase intention. The findings of this study revealed that information type and emotional appeal type influence consumer’s cognitive and emotional responses that in turn lead to purchase intention. The findings of this study will allow fair trade retailers to develop and manage their online website communication strategies in ways to enhance consumer purchase intention. ii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to take this opportunity to express my profound gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Stoel. I cannot thank her enough for her inspiring guidance, patience, continued support, and encouragement throughout my graduate program and the course of this thesis. -

The Generative Internet

The Generative Internet The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jonathan Zittrain, The Generative Internet, 119 Harvard Law Review 1974 (2006). Published Version doi:10.1145/1435417.1435426;doi:10.1145/1435417.1435426 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9385626 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ARTICLE THE GENERATIVE INTERNET Jonathan L. Zittrain TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................................1975 II. A MAPPING OF GENERATIVE TECHNOLOGIES....................................................................1980 A. Generative Technologies Defined.............................................................................................1981 1. Capacity for Leverage .........................................................................................................1981 2. Adaptability ..........................................................................................................................1981 3. Ease of Mastery....................................................................................................................1981 4. Accessibility...........................................................................................................................1982 -

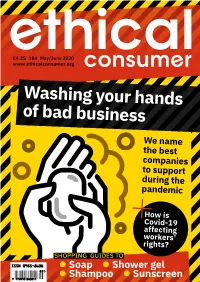

Ethical Consumer, Issue 184, May/June 2020

£4·25 184 May/June 2020 www.ethicalconsumer.org Washing your hands of bad business We name the best companies to support during the pandemic How is Covid-19 affecting workers’ rights? SHOPPING GUIDES TO l Soap l Shower gel l Shampoo l Sunscreen 2 Ethical Consumer May/June 2020 ETHICAL CONSUMER Editorial WHO’S WHO e hope that this magazine have started a Crowdfunder to raise THIS ISSUE’S EDITOR Tim Hunt finds you safe and well in money to help get essentials delivered to PROOFING Ciara Maginness (Little Blue Pencil) WRITERS/RESEARCHERS Jane Turner, Tim Hunt, these extraordinary times. people, alongside unions and grassroots Rob Harrison, Anna Clayton, Josie Wexler, For many, this is a period organisers operating in the area who Ruth Strange, Mackenzie Denyer, Clare Carlile, Wof extreme distress and anxiety. Loved we have come to know through our Francesca de la Torre, Alex Crumbie, Tom Bryson, ones may be sick, money may be tight, work. More details can be found on page Billy Saundry, Jasmine Owens REGULAR CONTRIBUTORS Simon Birch, Colin Birch and mental health may be suffering. The 47 and we hope that you will be in a DESIGN Tom Lynton list of problems caused by coronavirus position to donate, if you haven’t already. LAYOUT Adele Armistead (Moonloft), Jane Turner could fill a magazine (or a book). The generosity shown by many people COVER Tom Lynton In this issue, we’ve looked in depth at in the first hours of this appeal, (we CARTOONS Marc Roberts, Andy Vine, Mike Bryson, the impact of the coronavirus (and the reached our first target after just 4 Richard Liptrot subsequent lockdown) on the workers hours), also perhaps points towards the AD SALES Simon Birch SUBSCRIPTIONS Elizabeth Chater, who supply our modern consumer possibilities for a post-Covid world – a Francesca Thomas, Nadine Oliver markets, both in the UK and abroad. -

Relationship”

THE CONSUMER/STORE “RELATIONSHIP”: AN INTERPRETIVE INVESTIGATION OF UK WOMEN’S GROCERY SHOPPING EXPERIENCES by SUSAN YINGLIWAKENSHAW A Thesis submitted to the University of Lancaster in partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ProQuest Number: 11003576 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003576 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 THE CONSUMER/STORE “RELATIONSHIP”: AN INTERPRETIVE INVESTIGATION OF UK WOMEN’S GROCERY SHOPPING EXPERIENCES SUSAN YINGLI WAKENSDHAW June, 2011 ABSTRACT The phenomenon of consumer relationships in consumer markets has been investigated by loyalty and relationship research. However, mainstream consumer loyalty research has been developed in cognitive ‘attitude-behaviour’ framework. Nevertheless, relationship perspective has emerged as a theoretical perspective and attracted interest in the loyalty research domain. In addition, since the 1960s, relationship principles and relationship marketing (RM) concepts have also been developed in the B-to-B sectors and service markets. Moreover, relational thoughts and RM concepts have also been extended to mass consumer markets. Different types of commercial consumer relationships have been explored.