State of Play in Romania`S Road Infrastructure – a Comparative Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Safety Investment Program in Romania - AA-010269

CONSOLIDATED REPORT Framework agreement to support EIB advisory services (EIBAS) activities inside and outside EU-28 Lot 3: Transport Road Safety Investment Program in Romania - AA-010269 CONSULTING SAFEGE De Kleetlaan 5 B-1831 DIEGEM International Division SAFEGE SAS - SIÈGE SOCIAL Parc de l’Ile - 15/27 rue du Port 92022 NANTERRE CEDEX www.safege.com The authors take full responsibility for the contents of this report. The opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the view of the Advisory Hub, nor the European Investment Bank, nor the European Commission Road Safety Investment Program in Romania - AA-010269 Framework agreement to support EIB advisory services (EIBAS) activities inside and outside EU-28 Lot 3: Transport Document quality information General information Author(s) Ilie Bricicaru, Kristiana Chakarova, Matthew Chamberlain, Loreta Robertina Gherman, Razvan Iulian Mazilu Project name RSIP in Romania – AA-010269 Document name Consolidated Report on Road Safety Investment Program in Romania Date April 05th, 2021 Reference Version 4 Addressee(s) Sent to: Name Organisation Sent on (date): Kevin CHEUNG, Per MATHIASEN, Teodora TATARU EIB Borislava GABROVSKA EIAH, EIB 05.04.2021 Cristian Andrei, Flavius PAVAL, Denyssa PPELIN CNAIR Copy to: Name Organisation Sent on (date): Joanna TALLEC, Spiros TRIANTAFILLOS SUEZ Consulting 05.04.2021 History of modifications Version Date Written by Approved & signed by: Ilie BRICICARU, Kristiana CHAKAROVA, Version 1 20.01.2021 Matthew CHAMBERLAIN Loreta Robertina GHERMAN Razvan Iulian MAZILU Ilie -

Commercial Management and Financing of Roads (1998)

WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPER NO. 409 Work in progress for public discussion Commercial Management and Financing of Roads Iann G Heggie Piers Vickers RECENT WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPERS No. 334 Mosse and Sontheimer, PerformanceMonitoring Indicators Handbook No. 335 Kirmani and Le Moigne, FosteringRiparian Cooperation in InternationalRiver Basins:The World Bankat Its Best in DevelopmentDiplomacy No. 336 Francis, with Akinwumi, Ngwu, Nkom, Odihi, Olomajeye, Okunmadewa, and Shehu, State, Community, and LocalDevelopment in Nigeria No. 337 Kerf and Smith, PrivatizingAfrica's Infrastructure: Promise and Change No. 338 Young, MeasuringEconomic Benefits for WaterInvestments and Policies No. 339 Andrews and Rashid, The Financingof PensionSystems in Centraland EasternEurope: An Overviewof Major Trendsand TheirDeterminants, 1990-1993 No. 340 Rutkowski, Changesin the WageStructure during EconomicTransition in Centraland EasternEurope No. 341 Goldstein, Preker, Adeyi, and Chellaraj, Trendsin HealthStatus, Services,and Finance:The Transitionin Central and EasternEurope, Volume I No. 342 Webster and Fidler, editors, Le secteurinformel et lesinstitutions de microfinancementen Afrique de l'Ouest No. 343 Kottelat and Whitten, FreshwaterBiodiversity in Asia, with SpecialReference to Fish No. 344 Klugman and Schieber with Heleniak and Hon, A Survey of Health Reformin CentralAsia No. 345 Industry and Mining Division, Industry and Energy Department, A Mining Strategyfor LatinAmerica and the Caribbean No. 346 Psacharopoulos and Nguyen, The Roleof Governmentand the PrivateSector in Fighting Poverty No. 347 Stock and de Veen, ExpandingLabor-based Methodsfor RoadWorks in Africa No. 348 Goldstein, Preker, Adeyi, and Chellaraj, Trendsin Health Status, Services,and Finance:The Transitionin Central and EasternEurope, Volume 11, Statistical Annex No. 349 Cummings, Dinar, and Olson, New EvaluationProceduresfor a New Generationof Water-RelatedProjects No. -

Efficient and Innovative Designs and Technologies for Public Infrastructure Investments in Romania - Final Report

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 103461 Project co-financed from the European Regional development Fund through the OPTA 2007-2013 Advisory Services Agreement on Harmonizing State and EU Funded Projects in Regions Efficient and Innovative Designs and Technologies for Public Infrastructure Investments in Romania - Final Report - June 26, 2015 This report corresponds to the deliverable “Final Report on Efficient and Innovative Designs and Technologies for Public Infrastructure Investments In Romania” under component 3 “Assisting in improving the use of efficient designs and technologies in investment overseen by MRDPA” of the Advisory Services Agreement on ”Harmonizing State and EU Funded Projects in Regions” between the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, signed on May 27, 2014. This report was prepared by a core team comprised of Radoslaw Czapski, Antonio Nunez, Marcel Ionescu-Heroiu, Sebastian Burduja, Alina Burlacu, Marius Cristea, Florian Gaman, Oana Luca, Andrei Stănescu, Alina Armașu, and Cristian Postolache. The report benefited from thoughtful comments by peer reviewers: Thierry Davy, Antti Talvitie, Megan Schlotjes, Rakesh Tripathi, and Carmen Racanel. The team would like to thank Juan Gaviria and Jean-Francois Marteau for the advice, support, and guidance provided throughout the elaboration of this report. The team would also like to thank the counterparts in the Ministry of Regional Development and Public Administration for the timely feedback, the support offered in the elaboration of this study, and the excellent collaboration throughout. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views and position of the Executive Directors of the World Bank, the European Union, or the Government of Romania. -

Investigating the Role of Traffic Volume in The

Geographia Technica, Vol. 12, Issue 2, 2017, pp 20 to 29 EFFECTS OF TRAFFIC VOLUMES ON ACCIDENTS: THE CASE OF ROMANIA’S NATIONAL ROADS Rodica Dorina CADAR1, Melania Rozalia BOITOR1, Mara DUMITRESCU1 DOI: 10.21163/GT_2017.122.03 ABSTRACT: Every road accident is important. Investigating the road accidents and their causes is the main action to be conducted in the prevention and the prediction stages. The main aim of the paper is to investigate the state-of-the-art regarding road accidents research in Romania, one of the top country in the EU Road Death Statistics. It came out that there is an inconsistent research conducted in the country, with very few studies which were spread across different fields, along with a major lack in accident prediction methods. The study provides a starting point for the accident prediction by validating an international model which could be employed in Romania. The specific goal of the paper is to investigate the impact of the traffic volumes on the accidents occurrence. The traffic data were provided by the National Road Infrastructure Management Company (CNAIR). The road accident data were provided by the Traffic Department of the General Inspectorate of Romanian Police (GIRPTD) and it consisted in the information collected in the field during 2015 on the main national roads in Romania. The database was simplified in accordance to the aim of the paper to include only the relevant details regarding the accident, the vehicles, and the participants. The preliminary analyses were performed using Geographic Information System (GIS) software. The outcome was employed further in the research to highlight the correlation between accidents and the traffic volumes, by means of power regression. -

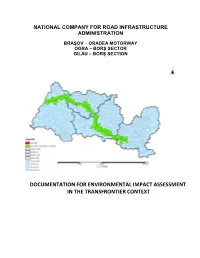

Documentation for Environmental Impact

NATIONAL COMPANY FOR ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE ADMINISTRATION BRAȘOV – ORADEA MOTORWAY OGRA – BORȘ SECTOR GILĂU – BORŞ SECTION DOCUMENTATION FOR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT IN THE TRANSFRONTIER CONTEXT “ Brașov – Oradea Motorway, sector Ogra – Borș” Documentation for environmental impact in the cross - border context Contents 1. Description of the proposed activity and its purpose .................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Purpose of the project ........................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Project description ................................................................................................................................................ 5 1.2.1. Longitudinal profille ............................................................................................................................................ 7 1.2.2. Transversal profile .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2.3. Thus the overall width of the transversal profile will be 27.5 m / 28.0 m. ............................................................... 8 1.2.4. The route: .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2.5. Works necessary to provide the rainwater drainage ............................................................................................11 -

National Administration of Roads

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 16153-RO Public Disclosure Authorized STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT ROMANIA Second Roads Project May 8, 1997 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Infrastructure Operations Division Country Department I Europe and Central Asia Region CURRENCY EOUIVALENTS (as of April 30, 1997) Currency Unit = Leu US$1 = 7,095 Lei 1 Leu = US$0.00014 AVERAGE EXCHANGE RATES Leu = US$1 1995 1996 January 1997 February 1997 March 1997 2,033 3,084 5,146 6,896 7,236 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ARL - Enterprise for Road Repairs and Works CEE - Central and East European EBRD - European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EIB - European Investment Bank EU - European Union HDM - Highway Design Model ICRS - Interministerial Committee for Road Safety IPTANA - Design Institute for Road, Water and Air Transport IRI - International Roughness Index MOT - Ministry of Transport NAR - National Administration of Roads NMT - Non-motorized transport PHARE - Fund for Assistance to Central and European Countries RA - Regie Autonome RAR - Romania Automobile Registry RD - Regional Directorate (of NAR) SICRS - Secretariat of the Interministerial Committee on Road Safety TERN - European Road Network VPD - Vehicles per day ROMANIA - FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Vice President: Johannes Linn, ECAVP Director: Kenneth G. Lay, ECIDR Division Chief: Ricardo Halperin, ECIIN Staff:: Charles Jeremy Lane (Senior Highway Engineer; Task Manager); Jacques Yenny (Principal Transport Economist); Sven-Ake Blomberg (Traffic Safety Engineer); Anca Dumitrescu (Project Officer, Resident Mission); Sudipto Sarkar, Environment Specialist Peer Reviewers were: E. Vasur (EC2ET) and S. Lundebye (SAIIN) STAFF APPRAISALREPORT ROMANIA SecondRoads Project CONTENTS LOAN AND PROJECT SUMMARY........ -

52Nd CONGRESS of EUROPEAN REGIONAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION August 21-25, 2012 BRATISLAVA, SLOVAKIA

52nd CONGRESS OF EUROPEAN REGIONAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION August 21-25, 2012 BRATISLAVA, SLOVAKIA THE SERVICES OF GENERAL INTEREST IN ROMANIA: LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL ASPECTS AT NATIONAL AND TERRITORIAL LEVEL Daniela L. Constantin, Raluca Petrescu, Claudiu Herteliu, Alina Iosif, Alina Profiroiu Bucharest Academy of Economic Studies, Romania Abstract. Before 1990 the services of general interest (SGI) in Romania were entirely provided by the public authorities. Afterwards, the market was gradually liberalized and the SGI captured the attention of private operators. Nowadays, the business sector is involved next to the public authorities in offering services of general interest so as to respond citizens’ expectations. The cooperation between the public authorities and the business sector is more developed in the area of SGI that prove to be profitable, such as waste service and public transport, rather than services that need high investments in infrastructure, such as electricity, gas and water supply service. Starting from these overall considerations this paper addresses the legal and institutional issues generated by the organising and the provision of SGI, with a particular emphasis on the territorial distribution of competences and the derived responsibilities. It takes into consideration the classification of competences associated to local authorities as a result of the decentralisation process, which are divided into exclusive, shared and delegated ones. Two territorial levels are considered, namely the counties - LAU1 (the same as NUTS3) and the localities (municipalities, towns and communes) – LAU 2. The development regions (NUTS2) are not considered as they are not administrative units and, consequently, do not have competences in the administration of the services of general interest. -

52Nd CONGRESS of EUROPEAN REGIONAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION August 21-25, 2012 BRATISLAVA, SLOVAKIA

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Constantin, Daniela L.; Petrescu, Raluca Mariana; Herteliu, Claudiu; Iosif, Alina; Profiroiu, Alina Conference Paper The Services Of General Interest In Romania: Legal And Institutional Aspects At National And Territorial Level 52nd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions in Motion - Breaking the Path", 21-25 August 2012, Bratislava, Slovakia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Constantin, Daniela L.; Petrescu, Raluca Mariana; Herteliu, Claudiu; Iosif, Alina; Profiroiu, Alina (2012) : The Services Of General Interest In Romania: Legal And Institutional Aspects At National And Territorial Level, 52nd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regions in Motion - Breaking the Path", 21-25 August 2012, Bratislava, Slovakia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/120723 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

P23 CAR Romania.Book

OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Romania This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries or those of the European Union. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Please cite this publication as: OECD (2016), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Romania, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264257450-en ISBN 978-92-64-25742-9 (print) ISBN 978-92-64-25745-0 (PDF) The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Photo credits: © Craitza/Shutterstock.com. Corrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/about/publishing/corrigenda.htm. © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of the source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. -

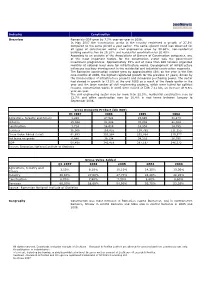

Industry Construction Overview Romania's GDP Grew by 7.7% Year-On-Year in 2006

Industry Construction Overview Romania's GDP grew by 7.7% year-on-year in 2006. In May 2007 the construction works in the country registered a growth of 27.5% compared to the same period a year earlier. The same upward trend was observed for all types of construction works: civil engineering grew by 30.60%, non-residential building construction by 25.10% and residential construction by 20.40%. According to an analysis of the Associations of Owners of Construction companies, one of the most important factors for the construction sector was the government investment programmes. Approximately 85% out of more than 800 tenders organized monthly at national level were for infrastructure works. Development of infrastructure influences auxiliary development in the residential and industrial construction segments. The Romanian construction market grew by approximately 18% on the year in the first nine months of 2006, the highest registered growth for the previous 17 years, driven by the rising number of infrastructure projects and increasing purchasing power. The sector had slowed in growth to 13.5% at the end 2005 as a result of the floods earlier in the year and the large number of civil engineering projects, which were halted for political reasons. Construction works in 2005 were valued at EUR 7.31 bln, an increase of 9.8% year-on-year. The civil engineering sector rose by more than 22.5%, residential construction rose by 12.7% and office construction rose by 10.4% in real terms between January to September 2006. Gross Domestic Product (bln -

Government of Ro Southern Ring

GOVERNMENT OF ROMANI A DEPARTMENT FOR INFRA STRUCTURE PROJECTS AND FOREIGN INVESTME NT SOUTHERN RING ROAD OF BUCHAREST (KM 52+770 - KM 100+765) + OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE OF BUCHAREST - PITESTI AND BUCHAREST - CONSTANTA MOTORWAYS – Concession Project Sheet – 1 1. PROJECT NAME Southern Ring Road of Bucharest (km 52+770 - km 100+765) + operation and maintenance of Bucharest - Pitesti and Bucharest - Constanta motorways 2. ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION 2.1 Internal rate of return (IRR) according to the Feasibility Study 9.8% (for the Southern Ring Road of Bucharest) 2.2. Project Costs Lei 1.827 billion (EUR 523 million), VAT not included, according to technical and economic indicators of 2007 (exchange rate 1 Euro = Lei 3.4943, December 21, 2007). The amount represents design costs + construction costs for the Southern Ring Road of Bucharest. The following costs will be added to this amount: Rehabilitation costs of Bucharest - Pitesti Motorway and other necessary equipment + Funding costs + Operation and maintenance costs + Reasonable profit for the concessionaire 3. DURATION OF CONCESSION AGREEMENT 30 years, of which: - 2 years design + construction - 28 years operation and maintenance In establishing this duration, significant aspects were taken into account, such as: value of the investment, level of involvement of the private sector and period required to ensure adequate return on capital employed. 4. ESTIMATED IMPLEMENTATION PERIOD 2014 – 2044 5. STARTING DATE OF THE PROCEDURE December 8, 2012 6. CURRENT STATUS OF THE PROJECT Prequalification stage; the deadline for submitting applications: February 28, 2013 2 7. PROJECT BENEFICIARY The Department for Infrastructure Projects and Foreign Investments in association with Compania Nationala de Autostrazi si Drumuri Nationale din Romania [Romanian National Company of Motorways and National Roads] . -

11Q9 Public Disclosure Authorized

WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPER NO. 409 w ~~~wTp4QOq Work in progress for public discussion may 11q9 Public Disclosure Authorized Commercial Management and Financing of Roads Public Disclosure Authorized _~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~W. '5 . Public Disclosure Authorized Y. t. ~~~~~fll G;....^t Public Disclosure Authorized i///l (;. JICUo-/s RECENT WORLD BANK TECHNICAL PAPERS No. 334 Mosse and Sontheimer, PerformanceMonitoring Indicators Handbook No. 335 Kirmani and Le Moigne, FosteringRiparian Cooperation in InternationalRiver Basins:The World Bankat Its Best in DevelopmentDiplomacy No. 336 Francis, with Akinwumi, Ngwu, Nkom, Odihi, Olomajeye, Okunmadewa, and Shehu, State, Community, and LocalDevelopment in Nigeria No. 337 Kerf and Smith, PrivatizingAfrica's Infrastructure: Promise and Change No. 338 Young, MeasuringEconomic Benefits for WaterInvestments and Policies No. 339 Andrews and Rashid, The Financingof PensionSystems in Centraland EasternEurope: An Overviewof Major Trendsand TheirDeterminants, 1990-1993 No. 340 Rutkowski, Changesin the WageStructure during EconomicTransition in Centraland EasternEurope No. 341 Goldstein, Preker, Adeyi, and Chellaraj, Trendsin HealthStatus, Services,and Finance:The Transitionin Central and EasternEurope, Volume I No. 342 Webster and Fidler, editors, Le secteurinformel et lesinstitutions de microfinancementen Afrique de l'Ouest No. 343 Kottelat and Whitten, FreshwaterBiodiversity in Asia, with SpecialReference to Fish No. 344 Klugman and Schieber with Heleniak and Hon, A Survey of Health Reformin CentralAsia No. 345 Industry and Mining Division, Industry and Energy Department, A Mining Strategyfor LatinAmerica and the Caribbean No. 346 Psacharopoulos and Nguyen, The Roleof Governmentand the PrivateSector in Fighting Poverty No. 347 Stock and de Veen, ExpandingLabor-based Methodsfor RoadWorks in Africa No. 348 Goldstein, Preker, Adeyi, and Chellaraj, Trendsin Health Status, Services,and Finance:The Transitionin Central and EasternEurope, Volume 11, Statistical Annex No.