Hold Your Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesia in View a CASBAA Market Research Report

Indonesia in View A CASBAA Market Research Report In Association with Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 6 1.1 Large prospective market providing key challenges are overcome 6 1.2 Fiercely competitive pay TV environment 6 1.3 Slowing growth of paying subscribers 6 1.4 Nascent market for internet TV 7 1.5 Indonesian advertising dominated by ftA TV 7 1.6 Piracy 7 1.7 Regulations 8 2. FTA in Indonesia 9 2.1 National stations 9 2.2 Regional “network” stations 10 2.3 Local stations 10 2.4 FTA digitalization 10 3. The advertising market 11 3.1 Overview 11 3.2 Television 12 3.3 Other media 12 4. Pay TV Consumer Habits 13 4.1 Daily consumption of TV 13 4.2 What are consumers watching 13 4.3 Pay TV consumer psychology 16 5. Pay TV Environment 18 5.1 Overview 18 5.2 Number of players 18 5.3 Business models 20 5.4 Challenges facing the industry 21 5.4.1 Unhealthy competition between players and high churn rate 21 5.4.2 Rupiah depreciation against US dollar 21 5.4.3 Regulatory changes 21 5.4.4 Piracy 22 5.5 Subscribers 22 5.6 Market share 23 5.7 DTH is still king 23 5.8 Pricing 24 5.9 Programming 24 5.9.1 Premium channel mix 25 5.9.2 SD / HD channel mix 25 5.9.3 In-house / 3rd party exclusive channels 28 5.9.4 Football broadcast rights 32 5.9.5 International football rights 33 5.9.6 Indonesian Soccer League (ISL) 5.10 Technology 35 5.10.1 DTH operators’ satellite bands and conditional access system 35 5.10.2 Terrestrial technologies 36 5.10.3 Residential DTT services 36 5.10.4 In-car terrestrial service 36 5.11 Provincial cable operators 37 5.12 Players’ activities 39 5.12.1 Leading players 39 5.12.2 Other players 42 5.12.3 New entrants 44 5.12.4 Players exiting the sector 44 6. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Gambaran Umum Objek Penelitian Pay-Tv

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Gambaran Umum Objek Penelitian Pay-tv atau televisi berbayar adalah jenis televisi yang memberikan saluran penyiaran khusus kepada pemirsa yang bersedia membayar (berlangganan) secara berkala, televisi berbayar biasanya disediakan dengan menggunakan sistem digital ataupun analog (sumber: www.publikasi.bps.go.id, diakses 1 Mei 2015). Sehingga pay-tv berbeda dengan televisi free-to-air dimana penyiarannya dilakukan secara gratis. Televisi berbayar di dunia pertama kali diperkenalkan oleh Zeinth Radio Corporation pada tahun 1949. Layanannya diberi nama Phonevision sebab cara kerjanya adalah memesan tayangan tertentu melalui telepon yang sifatnya tidak free-to-air. (Arga, 2008). Pada tahun 1953 Internasional Telemeter Corporation yang dimiliki oleh Paramount Pictures meluncurkan sebuah kombinasi antara antena dengan kabel yang menghasilkan variasi lainnya dari televisi berbayar. Pelanggan tidak dikenakan biaya untuk menyaksikan program biasa, biaya hanya dikenakan bagi program khusus dengan cara memasukan sejumlah uang logam ke dalam perangkat yang telah ditambahkan pada televisi mereka masing-masing. Kemudian Telemovies diluncurkan di Bartlesvile, Oklahoma pada tahun 1957. Layanan yang diluncurkan oleh Video Independent Theaters ini menawarkan sebuah first-run movie channel, yaitu channel khusus yang menayangkan semua film–film bioskop pertama kali setelah turun dari layar lebar. Telemovie pun merupakan televisi berbayar pertama yang membebankan biaya flat perbulan kepada pelanggannya tanpa melihat seberapa banyak penggunaannya -

Rebel Trouble for Trs in Civic Polls

Follow us on: RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 12 HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW NEED FOR SENSEX ENDS 52 PTS LOWER, IMPROVED THAKUR BECOMES BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH MULTILATERALISM NIFTY HOLDS 12K BETTER T20 BOWLER BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN VIJAYAWADA *LATE CITY VOL. 2 ISSUE 90 HYDERABAD, THURSDAY JANUARY 9, 2020; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable RAVIPUDI IS JANDHYALA'S ‘EKALAVYA SHISYA' { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com DEEPIKA PADUKONE PART OF WHATSAPP ADMINS IN LEH, KARGIL TWEET URGING TWITTER TO SUSPEND INDIA ASKS CITIZENS TO AVOID ‘TUKDE TUKDE GANG': BJP MP TOLD TO REGISTER WITH POLICE TRUMP'S ACCOUNT GOES VIRAL NON-ESSENTIAL TRAVEL TO IRAQ day after Bollywood diva Deepika Padukone's sudden visit to he police in the newly formed Union s tension between the US and Iran mount after Tehran fired over a he government on Wednesday issued a AJNU, controversial BJP MP Sakshi Maharaj on TTerritory of Ladakh have urged admins Adozen missiles on two US bases in Iraq, a Twitter user's post, Ttravel advisory, asking citizens to avoid Wednesday used unusually strong words against her, of WhatsApp groups to register addressed to Twitter to suspend the account of US non-essential travel to Iraq in view of calling Padukone part of 'tukde tukde gang'. In an themselves at the police stations in Leh President Donald Trump — without naming him — prevailing situation in the Gulf country. In interview to IANS, the Unnao MP alleged, "I think they and Kargil. The police released a to prevent war, has gone viral. -

IRS on Behalf of Nonbelief Relief Preferential Treatment Treatment of Churches Vis-À-Vis Other Tax-Exempt Nonprofits

Graduate / ‘older’ Why do we The bible student essay portray atheists as taught me that contest winners broken believers? God is a jerk PAGE 12-17 PAGE 5 PAGE 6 Vol. 35 No. 9 Published by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc. November 2018 FFRF sues IRS on behalf of Nonbelief Relief Preferential treatment treatment of churches vis-à-vis other tax-exempt nonprofits. Nonbelief given to churches over Relief’s tax exemption was revoked annual financial report on Aug. 20 for failure to file the Form 990 return for three consecutive years. FFRF is taking the Internal Revenue Nonbelief Relief “has and will suffer Associated Press Service to court over yet another reli- harm, detriment and disadvantage as President Trump shows off the “religious freedom” executive order he signed on gion-related tax privilege. a result of the revocation of its tax- May 4, 2017, in the Rose Garden, surrounded by members of the faith community The national state/church watch- exempt status, including tax liabilities and Vice President Pence. dog filed a federal lawsuit Oct. 10 in and loss of charitable donations D.C. district court to challenge the which are no longer tax-deductible by preferential exemption of churches donors.” New Treasury report vindicates and related organiza- Nonbelief Relief is tions from reporting asking the court to re- FFRF’s stance on politicking ban annual information instate its tax-exempt returns required of status, and to enjoin FFRF welcomes a new report high- openly flout the law and are not held all other tax-exempt the IRS from continu- lighting deficiencies in the IRS’ en- accountable.” groups. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

MAHARASHTRA Not Mention PN-34

SL Name of Company/Person Address Telephone No City/Tow Ratnagiri 1 SHRI MOHAMMED AYUB KADWAI SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM A MULLA SHWAR 2 SHRI PRAFULLA H 2232, NR SAI MANDIR RATNAGI NACHANKAR PARTAVANE RATNAGIRI RI 3 SHRI ALI ISMAIL SOLKAR 124, ISMAIL MANZIL KARLA BARAGHAR KARLA RATNAGI 4 SHRI DILIP S JADHAV VERVALI BDK LANJA LANJA 5 SHRI RAVINDRA S MALGUND RATNAGIRI MALGUN CHITALE D 6 SHRI SAMEER S NARKAR SATVALI LANJA LANJA 7 SHRI. S V DESHMUKH BAZARPETH LANJA LANJA 8 SHRI RAJESH T NAIK HATKHAMBA RATNAGIRI HATKHA MBA 9 SHRI MANESH N KONDAYE RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 10 SHRI BHARAT S JADHAV DHAULAVALI RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 11 SHRI RAJESH M ADAKE PHANSOP RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 12 SAU FARIDA R KAZI 2050, RAJAPURKAR COLONY RATNAGI UDYAMNAGAR RATNAGIRI RI 13 SHRI S D PENDASE & SHRI DHAMANI SANGAM M M SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR EHSWAR 14 SHRI ABDULLA Y 418, RAJIWADA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI TANDEL RI 15 SHRI PRAKASH D SANGAMESHWAR SANGAM KOLWANKAR RATNAGIRI EHSWAR 16 SHRI SAGAR A PATIL DEVALE RATNAGIRI SANGAM ESHWAR 17 SHRI VIKAS V NARKAR AGARWADI LANJA LANJA 18 SHRI KISHOR S PAWAR NANAR RAJAPUR RAJAPUR 19 SHRI ANANT T MAVALANGE PAWAS PAWAS 20 SHRI DILWAR P GODAD 4110, PATHANWADI KILLA RATNAGI RATNAGIRI RI 21 SHRI JAYENDRA M DEVRUKH RATNAGIRI DEVRUK MANGALE H 22 SHRI MANSOOR A KAZI HALIMA MANZIL RAJAPUR MADILWADA RAJAPUR RATNAGI 23 SHRI SIKANDAR Y BEG KONDIVARE SANGAM SANGAMESHWAR ESHWAR 24 SHRI NIZAM MOHD KARLA RATNAGIRI RATNAGI 25 SMT KOMAL K CHAVAN BHAMBED LANJA LANJA 26 SHRI AKBAR K KALAMBASTE KASBA SANGAM DASURKAR ESHWAR 27 SHRI ILYAS MOHD FAKIR GUMBAD SAITVADA RATNAGI 28 SHRI -

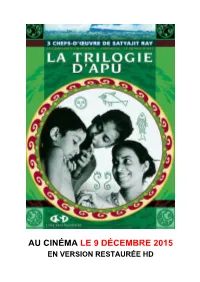

Satyajit Ray

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

The Indian Police Journal O U R N a L L V

LV No.3 JULY-SEPTEMBER, 2008 lR;eso t;rs T h e I n d i a n P o l i c e J The Indian Police Journal o u r n a l L V N O . 3 J u l y - S e p t e m b e r , 2 0 Published By : The Bureau of Police Research & Development, Ministry of Home Affairs, 0 Govt. of India, New Delhi and Printed at Chandu Press, D-97, Shakarpur, Delhi-110092 8 PROMOTING GOOD PRACTICES & STANDARDS BOARD OF REFEREES 10. Shri Sanker Sen, Sr. Fellow, Institute of Social Sciences, 8, Nelson Mandela Road, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070 Ph. : 26121902, 26121909 11. Justice Iqbal Singh, House No. 234, Sector-18A, Chandigarh 12. Prof. Balraj Chauhan, Director, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia National Law University, LDA Kanpur Road Scheme, Lucknow - 226012 13. Prof. M.Z. Khan, B-59, City Apartments, 21, Vasundhra Enclave, New Delhi 14. Prof. Arvind Tiwari, Centre for Socio-Legal Study & Human Rights, Tata Institute of Social Science, Chembur, Mumbai lR;eso t;rs 15. Prof. J.D. Sharma, Head of the Dept., Dept. of Criminology and Forensic Science, Dr. Harisingh Gour Vishwavidyalaya, Sagar - 470 003 (MP) 16. Dr. Jitendra Nagpal, Psychiatric and Expert on Mental Health, VIMHANS, 1, Institutional Area, Nehru Nagar, New Delhi-110065 17. Dr. J.R. Gour, The Indian Police Journal Director, State Forensic Science Vol. LV-No.3 Laboratory, July-September, 2008 Himachal Pradesh, Junga - 173216 18. Dr. A.K. Jaiswal, Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, AIIMS, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi-110029 Opinions expressed in this journal do not reflect the policies or views of the Bureau of Police Research & Development, but of the individual contributors. -

Appellate Jurisdiction

Appellate Jurisdiction Daily Supplementary List Of Cases For Hearing On Friday, 12th of February, 2021 CONTENT SL COURT PAGE BENCHES TIME NO. ROOM NO. NO. HON'BLE CHIEF JUSTICE THOTTATHIL B. 1 On 12-02-2021 1 RADHAKRISHNAN 1 DB -I At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJESH BINDAL 16 On 12-02-2021 2 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE ANIRUDDHA ROY DB - II At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 3 On 12-02-2021 3 32 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE I. P. MUKERJI 37 On 12-02-2021 4 33 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBHASIS DASGUPTA DB - III At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE HARISH TANDON 2 On 12-02-2021 5 34 HON'BLE JUSTICE KAUSIK CHANDA DB- IV At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 12-02-2021 6 45 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAVI KRISHAN KAPUR DB At 01:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE SOUMEN SEN 12 On 12-02-2021 7 46 HON'BLE JUSTICE SAUGATA BHATTACHARYYA DB-V At 10:45 AM HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 11 On 12-02-2021 8 48 HON'BLE JUSTICE HIRANMAY BHATTACHARYYA DB - VI At 10:45 AM 11 On 12-02-2021 9 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 54 SB At 02:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 28 On 12-02-2021 10 58 HON'BLE JUSTICE TIRTHANKAR GHOSH DB - VII At 10:45 AM 28 On 12-02-2021 11 HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY 75 SB - I At 03:00 PM HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 4 On 12-02-2021 12 78 HON'BLE JUSTICE SUVRA GHOSH DB - VIII At 10:45 AM 4 On 12-02-2021 13 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARINDAM SINHA 82 SB - II At 03:00 PM 38 On 12-02-2021 14 HON'BLE JUSTICE ARIJIT BANERJEE 86 SB At 10:45 AM 9 On 12-02-2021 15 HON'BLE JUSTICE SHIVAKANT PRASAD 111 SB - II At 10:45 AM 13 On 12-02-2021 16 HON'BLE JUSTICE RAJASEKHAR MANTHA 116 SB - III At 10:45 AM 8 On 12-02-2021 17 HON'BLE JUSTICE SABYASACHI BHATTACHARYYA 126 SB - IV At 10:45 AM SL NO. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

The Catholic Bishops' Conference of India

THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS’ CONFERENCE OF INDIA Vol. XXVII India January- December 2018 GUEST EDITORIAL never did anything worth doing by accident, nor did any of my inventions come by accident; they came by work”. These words “I of the great Greek Philosopher Plato in brief summarises this first edition of the refurbished “Catholic India” information magazine of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of India. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference as the apex body of the Catholic Church in India through its Office Bearers and its various offices continuously conducts programmes and activities in favour of society and for the animation of the Church in India. Many of these activities which our Bishops, Fathers and Sisters do, not by accident, but through hard work and much effort are regularly reported on ourwebsite https://www.cbci.in . Over the last 15 months, the website has been visited by over three million surfers. The newsletter Catholic India which now comes out both as an electronic edition as well as a printed one provides just the gist of a few of the activities/happenings/events with a link to the detailed report on the website. This is a novel experiment to make the website news easily accessible to our friends, benefactors and well-wishers interested in our activities. We take this opportunity to thank all those who have made it possible to bring forth this publication. In particular my sincere thanks to Fr. Anthony Fernandes SFX who has compiled and set up the news magazine and to the Manager of Federal Bank, Connaught Place branch, New Delhi, for sponsoring the costs of its publication. -

Annual Report 2018-19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 Towards a new dawn Ministry of Women and Child Development Government of India ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 MINISTRY OF WOMEN AND CHILD DEVELOPMENT Government of India CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. Chapter 1. Introduction 1-4 Chapter 2. Women Empowerment and Protection 5-28 Chapter 3. Child Development 29-55 Chapter 4. Child Protection and Welfare 57-72 Chapter 5. Gender and Child Budgeting 73-81 Chapter 6. Plan, Statistics and Research 83-91 Chapter 7. Food and Nutrition Board 93-101 Chapter 8. National Institute of Public Cooperation and Child Development 103-115 Chapter 9. Central Social Welfare Board 117-128 Chapter 10. National Commission for Women 129-139 Chapter 11. Rashtriya Mahila Kosh 141-149 Chapter 12. National Commission for Protection of Child Rights 151-167 Chapter 13. Central Adoption Resource Authority 169-185 Chapter 14. Other Programme and Activities 187-200 Annexures 201-285 1 Introduction Annual Report 2018-19 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 The Ministry of Women and Child concerns, creating awareness about their rights and Development is the apex body of Government facilitating institutional and legislative support for of India for formulation and administration of enabling them to realize their human rights and regulations and laws related to women and child develop to their full potential. development. It came into existence as a separate Ministry with effect from 30th January, 2006; III. MISSION – CHILDREN earlier, it was the Department of Women and 1.4 Ensuring development, care and protection Child Development set up in the year 1985 under of children through cross-cutting policies and the Ministry of Human Resource Development.