Money and Punishment, Circa 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced

Ellies 2018 Finalists Announced New York, The New Yorker top list of National Magazine Award nominees; CNN’s Don Lemon to host annual awards lunch on March 13 NEW YORK, NY (February 1, 2018)—The American Society of Magazine Editors today published the list of finalists for the 2018 National Magazine Awards for Print and Digital Media. For the fifth year, the finalists were first announced in a 90-minute Twittercast. ASME will celebrate the 53rd presentation of the Ellies when each of the 104 finalists is honored at the annual awards lunch. The 2018 winners will be announced during a lunchtime presentation on Tuesday, March 13, at Cipriani Wall Street in New York. The lunch will be hosted by Don Lemon, the anchor of “CNN Tonight With Don Lemon,” airing weeknights at 10. More than 500 magazine editors and publishers are expected to attend. The winners receive “Ellies,” the elephant-shaped statuettes that give the awards their name. The awards lunch will include the presentation of the Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame Award to the founding editor of Metropolitan Home and Saveur, Dorothy Kalins. Danny Meyer, the chief executive officer of the Union Square Hospitality Group and founder of Shake Shack, will present the Hall of Fame Award to Kalins on behalf of ASME. The 2018 ASME Award for Fiction will also be presented to Michael Ray, the editor of Zoetrope: All-Story. The winners of the 2018 ASME Next Awards for Journalists Under 30 will be honored as well. This year 57 media organizations were nominated in 20 categories, including two new categories, Social Media and Digital Innovation. -

Freelance Journalists Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah and Abe Streep Named 2019 Recipients of the American Mosaic Journalism Prize

Freelance Journalists Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah and Abe Streep Named 2019 Recipients of the American Mosaic Journalism Prize Los Altos, Calif. (February 5, 2019) – The Heising-Simons FounDation announceD toDay that freelance journalists Rachel KaaDzi Ghansah anD Abe Streep are the 2019 recipients of the American Mosaic Journalism Prize. Both writers were surprised with an unrestricted cash prize of $100,000. The prize is awarDed for excellence in long-form, narrative or deep reporting about unDerrepresenteD anD/or misrepresenteD groups in the American lanDscape. Ms. Ghansah anD Mr. Streep join 2018 recipients Jaeah Lee anD Valeria FernánDez as the freelance journalists to receive this new journalism prize, first awardeD last year. The prize is based on confidential nominations from leaders in journalism throughout the country. The recipients were selected by 10 esteemed judges who this year included journalists from the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, NBC/TelemunDo, NPR, BuzzfeeD News, Columbia University anD Barnard College, anD freelance journalism. The American Mosaic Journalism Prize recognizes journalism’s critical ability to foster greater understanding and aims to recognize and empower exceptional freelance journalists. It recognizes that in toDay’s journalism, freelancers are both vulnerable anD valuable. Many journalists work without the support of an institution anD with limiteD resources. AnD yet, some of the most important works of journalism come from freelance journalists who commit long perioDs of time to their subjects. The 2019 Recipients: Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah “Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s deeply reported and essayistic writing pushes the form of longform journalism, ranging from a poignant profile of master painter Henry Taylor to a searing exposé of the hotbed of racism and white supremacy that fueled the heinous murder of nine African-Americans in Charleston, South Carolina. -

Lone Wolf Terrorism: Types, Stripes, and Double Standards†

Copyright 2018 by Khaled A. Beydoun Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 112, No. 5 Online Essays LONE WOLF TERRORISM: TYPES, STRIPES, AND DOUBLE STANDARDS† Khaled A. Beydoun ABSTRACT—The recent spike in mass shootings, topped by the October 1, 2017, Las Vegas massacre, dubbed the “deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history,” has brought newfound urgency and attention to lone wolf violence and terrorism. Although a topic of pressing concern, the phenomenon—which centers on mass violence inflicted by one individual— is underexamined and undertheorized within legal literature. This scholarly neglect facilitates flat understandings of the phenomenon and enables the racial and religious double standards arising from law enforcement investigations and prosecutions of white and Muslim lone wolves. This Essay contributes a timely reconceptualization of the phenomenon, coupled with a typology adopted from social science, for understanding the myriad forms of lone wolf terrorism. In addition to contributing the theoretical frameworks to further examine lone wolf terrorism within legal scholarship, this Essay examines how the assignment of the lone wolf designation by law enforcement functions as: (1) a presumptive exemption from terrorism for white culprits and (2) a presumptive connection to terrorism for Muslim culprits. This asymmetry is rooted in the distinct racialization of white and Muslim identity, and it is driven by War on Terror baselines that profile Muslim identity as presumptive of a terror threat. AUTHOR—Khaled A. Beydoun, Associate Professor of Law, University of Detroit Mercy School of Law; Senior Affiliated Faculty, University of California at Berkeley, Islamophobia Research & Documentation Project † This Essay was originally published in the Northwestern University Law Review Online on February 22, 2018. -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Read the Full Brief Here

USCA Case #18-5276 Document #1770356 Filed: 01/25/2019 Page 1 of 59 ORAL ARGUMENT NOT SCHEDULED No. 18-5276 _____________________________ _____________________________ JASON LEOPOLD AND REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, Appellants, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee. ____________________________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA No. 1:13-mc-00712 (Howell, C.J.) BRIEF OF MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS Laura R. Handman Selina MacLaren DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP 1919 Pennsylvania Avenue NW 865 South Figueroa Street Suite 800 Suite 2400 Washington, D.C. 20006-3402 Los Angeles, C.A. 90017-2566 (202) 973-4200 (213) 633-8617 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Media Organizations USCA Case #18-5276 Document #1770356 Filed: 01/25/2019 Page 2 of 59 STATEMENT REGARDING CONSENT TO FILE AND SEPARATE BRIEFING Pursuant to D.C. Circuit Rule 29(b), undersigned counsel for amici curiae media organizations represents that both parties have been sent notice of the filing of this brief and have consented to the filing.1 Pursuant to D.C. Circuit Rule 29(d), undersigned counsel for amici curiae certifies that a separate brief is necessary to provide the perspective of media organizations and reporters whose reporting depends on access to court records. Access to such records allows the press to inform the public about the judiciary, the criminal justice system, surveillance trends, and local crime. Access to the type of surveillance-related records sought here would also inform the press about when the government targets journalists for surveillance and how existing press protections, which shield journalistic work product from intrusive government surveillance, apply tojournalists’electronicdata.Amici are thus particularly well-situated to provide the Court with insight into the public interest value of unsealing court records, generally, and the surveillance-related court records requested here, in particular. -

Genealogies of Capture and Evasion: a Radical Black Feminist Meditation for Neoliberal Times by Lydia M. Kelow-Bennett B.A

Genealogies of Capture and Evasion: A Radical Black Feminist Meditation for Neoliberal Times By Lydia M. Kelow-Bennett B.A., University of Puget Sound, 2002 M.A., Georgetown University, 2011 A.M., Brown University, 2016 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy in the Department of Africana Studies at Brown University Providence, RI May 2018 © Copyright 2018 by Lydia Marie Kelow-Bennett This dissertation by Lydia M. Kelow-Bennett is accepted in its present form by the Department of Africana Studies as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date________________ ______________________________ Matthew Guterl, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date________________ ______________________________ Anthony Bogues, Reader Date________________ ______________________________ Françoise Hamlin, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date________________ ____________________________________ Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii [CURRICULUM VITAE] Lydia M. Kelow-Bennett was born May 13, 1980 in Denver, Colorado, the first of four children to Jerry and Judy Kelow. She received a B.A. in Communication Studies with a minor in Psychology from the University of Puget Sound in 2002. Following several years working in education administration, she received a M.A. in Communication, Culture and Technology from Georgetown University in 2011. She received a A.M. in Africana Studies from Brown University in 2016. Lydia has been a committed advocate for students of color at Brown, and served as a Graduate Coordinator for the Sarah Doyle Women’s Center for a number of years. She was a 2017-2018 Pembroke Center Interdisciplinary Opportunity Fellow, and will begin as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan in Fall 2018. -

NYU Law Review

41136-nyu_94-1 Sheet No. 3 Side A 04/08/2019 11:46:01 \\jciprod01\productn\N\NYU\94-1\NYU101.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-APR-19 11:26 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 94 APRIL 2019 NUMBER 1 ARTICLES AFROFUTURISM, CRITICAL RACE THEORY, AND POLICING IN THE YEAR 2044 I. BENNETT CAPERS* In 2044, the United States is projected to become a “majority-minority” country, with people of color making up more than half of the population. And yet in the public imagination—from Robocop to Minority Report, from Star Trek to Star Wars, from A Clockwork Orange to 1984 to Brave New World—the future is usu- ally envisioned as majority white. What might the future look like in year 2044, when people of color make up the majority in terms of numbers, or in the ensuing years, when they also wield the majority of political and economic power? And specifically, what might policing look like? This Article attempts to answer these questions by examining how artists, cybertheorists, and speculative scholars of color—Afrofuturists and Critical Race Theorists—have imagined the future. What can we learn from Afrofuturism, the term given to “speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns [in the con- text of] techno culture?” And what can we learn from Critical Race Theory and its 41136-nyu_94-1 Sheet No. 3 Side A 04/08/2019 11:46:01 “father” Derrick Bell, who famously wrote of space explorers to examine issues of race and law? What do they imagine policing to be, and what can we imagine policing to be in a brown and black world? * Copyright © 2019 by I. -

H-Wpl Readers Book Discussion Group

H-WPL READERS BOOK DISCUSSION GROUP FEBRUARY 2016 Monday, February 22, 2016, at 1:00 P.M. God Help the Child, by Toni Morrison Discussion Leader: Candace Plotsker-Herman Spare and unsparing, the first novel by Toni Morrison to be set in our current moment—weaves a tale about the way the sufferings of childhood can shape, and misshape, the life of the adult. At the center: a young woman who calls herself Bride, whose stunning blue-black skin is only one element of her beauty, her boldness and confidence, her success in life, but which caused her light-skinned mother to deny her even the simplest forms of love. There is Booker, the man Bride loves, and loses to anger. Rain,the mysterious white child with whom she crosses paths. And finally, Bride’s mother herself, Sweetness, who takes a lifetime to come to understand that “what you do to children matters. And they might never forget.” Monday, March 14, 2016, at 1:00 P.M. My Brilliant Friend, by Elena Ferrante Discussion Leader: Edna Ritzenberg In a poor, midcentury Italian neighborhood, two girls, Elena and Lila, exhibit remarkable intelligence early in school, at a time when money is scarce and education a privilege, especially for girls. Through the lives of these two women, Ferrante tells the story of a neighborhood, a city and a country as it is transformed in ways that, in turn, also transform the relationship between her two protagonists. God Help the Child review -- Toni Morrison continues to improve with age. By Bernardine Evaristo, The Observer: 39. -

Online Radicalization Behaviors by Violent Extremist Type

ONLINE RADICALIZATION BEHAVIORS BY VIOLENT EXTREMIST TYPE by Halle Baltes A research study submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Global Security Studies Baltimore, Maryland May 2021 © 2021 Halle Baltes All Rights Reserved Abstract Existing research suggests that different types of violent extremist organizations utilize distinct approaches to radicalize and mobilize potential recruits online. Specifically, previous studies indicate that Violent Islamic Extremist (VIE) groups attempt to create virtual breeding grounds that mimic in-person socialization. Conversely, Radical Right Extremist (RRE) organizations forgo web-based community-building efforts, preferring instead to proliferate mass amounts of alternative ideological propaganda to subvert mainstream narratives. There is little research examining whether the phenomenon continues at the actor level among the individuals actually committing terrorist attacks. Therefore, this study qualitatively investigates whether web-based behaviors differ by actor type through a comparative case study analysis. To do so, the research explores the radicalization of perpetrators prior to six terrorist attacks in the United States. The study tests the hypotheses that internet behaviors vary by actor type (H1), with VIE subjects presenting more interactive online engagement (HIa) and RRE subjects showing more one-way absorption of information (H1b). The resulting evidence does not support the hypotheses as little discernible difference has been discovered between the online radicalization behaviors that VIE and RRE actors partook in. In fact, the results suggest that if a difference does exist, it is that RRE perpetrators engage in more online interaction than VIE counterparts. However, this slight discrepancy results from a case with inconclusive data due to contradictory reports. -

The 2018 Prize Winners

THE 2018 PRIZE WINNERS Columbia University today announced the 2018 Pulitzer Prizes, awarded on the recommendation oF the Pulitzer Prize Board. JOURNALISM BREAKING NEWS PHOTOGRAPHY Ryan Kelly oF The Daily Progress, Charlottesville, Va. PUBLIC SERVICE FEATURE PHOTOGRAPHY The New York Times and The New Yorker Photography StaFF oF Reuters BREAKING NEWS REPORTING StafF of The Press Democrat, Santa Rosa, CaliF. LETTERS, DRAMA AND MUSIC INVESTIGATIVE REPORTING StafF of The Washington Post FICTION EXPLANATORY REPORTING Less by Andrew Sean Greer (Lee Boudreaux Books/ StafFs of The Arizona Republic and USA Today Network Little, Brown and Company) LOCAL REPORTING DRAMA StafF of The Cincinnati Enquirer Cost of Living by Martyna Majok NATIONAL REPORTING HISTORY StafFs oF The New York Times and The Washington Post The GulF: The Making oF an American Sea by Jack E. Davis INTERNATIONAL REPORTING (Liveright/W.W. Norton) Clare Baldwin, Andrew R.C. Marshall and Manuel Mogato BIOGRAPHY of Reuters Prairie Fires: The American Dreams oF Laura Ingalls FEATURE WRITING Wilder by Caroline Fraser (Metropolitan Books) Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, Freelance reporter, GQ POETRY COMMENTARY HalF-light: Collected Poems 1965-2016 by Frank Bidart John Archibald of Alabama Media Group, (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) Birmingham, Ala. GENERAL NONFICTION CRITICISM Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black Jerry Saltz of New York magazine America by James Forman Jr. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) EDITORIAL WRITING MUSIC Andie Dominick of The Des Moines Register Damn. by Kendrick Lamar, recording released on April 14, 2017. EDITORIAL CARTOONING Jake Halpern, freelance writer, and Michael Sloan, freelance cartoonist, The New York Times The Pulitzer Prizes, Columbia University, 709 Pulitzer Hall, 2950 Broadway, New York, NY 10027 THE 2018 PRIZES IN JOURNALISM 1. -

Examining Subjectivity and Trauma in American Literary Journalism

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Spring 5-2021 Speak for Yourself: Examining Subjectivity and Trauma in American Literary Journalism Nathaniel Poole Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPEAK FOR YOURSELF: EXAMINING SUBJECTIVITY AND TRAUMA IN AMERICAN LITERARY JOURNALISM by Nathaniel Poole A Thesis Submitted to Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (English) The Honors College The University of Maine May 2021 Advisory Committee: Caroline Bicks, Stephen E. King Chair in Literature, Advisor Gregory Howard, Associate Professor of English Naomi Jacobs, Professor Emeritus of English Mark Brewer, Professor of Political Science Michael J. Socolow, Associate Professor of Communications and Journalism ABSTRACT Due to their relevance and emotional draw for readers, stories of tragedy and suffering are a nearly inescapable aspect of journalism. However, the routine reporting and formulaic styles associated with coverage of these events has contributed to audience compassion fatigue. Studies have been done on the success of some journalists who have historically pushed the boundaries of style and deployed literary strategies to elicit emotion and subvert compassion fatigue in their reporting. However, there is more room in the scholarship on this subject for studies of the specific strategies that contemporary literary journalism writers use and how they adapt them to the nuances of their subjects. -

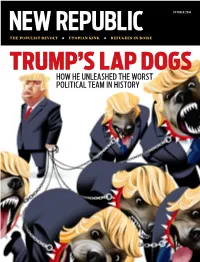

HOW HE UNLEASHED the WORST POLITICAL TEAM in HISTORY New from COLUMBIA University Press

OCTOBER 2016 THE POPULIST REVOLT UTOPIAN KINK REFUGEES IN BOISE TRUMP’S LAP DOGS HOW HE UNLEASHED THE WORST POLITICAL TEAM IN HISTORY New from COLUMBIA UnIvERsIty PREss A History of Virility Reductionism in Art ALAIN CORBIN, JEAN- and Brain Science JACQUES COURTINE, Bridging the Two Cultures GEORGES VIGARELLO, ERIC R. KANDEL EDS. “[A] fascinating survey of mind Translated by Keith Cohen science and modern art. “A sweeping history of Kandel presents concepts to masculinity in the tradition of ponder that may open new Ariès and Duby’s A History of avenues of art making and Private Life.” neuroscientific endeavor.” —Lewis Seifert, Brown —Publishers Weekly University Exhaustion A Brief History of A History Entrepreneurship ANNA KATHARINA The Pioneers, Profiteers, and SCHAFFNER Racketeers Who Shaped Our “When Exhaustion does World bring theory and experience JOE CARLEN together, it becomes “This enjoyable book is full engrossing—which makes it all of great stories and practical the more regrettable that for so ideas.” many centuries, our exhausted ancestors remained silent.” —Brian Tracy, author of The Way to Wealth —New Republic Deciding Data Love What’s True The Seduction and Betrayal of The Rise of Political Digital Technologies Fact-Checking ROBERTO SIMANOWSKI in American Journalism Translated by Brigitte Pichon, Dorian LUCAS GRAVES Rudnytsky, and John Cayley “Brilliant . an ironic and “A lively page-turner . critical take on contemporary that also digs deep into the society’s ambivalent very foundations of public relationship with data.” knowledge. What do we really know, and how do we know —Saskia Sassen, author of it? Graves provides thought- Expulsions provoking answers.” —Rodney Benson, New York University CUP.COLUMBIA.EDU • CUPBLOG.ORG contents OCTOBER 2016 UP FRONT Beyond the Killing Fields Can tourism help Cambodia face its brutal past? BY BRENT CRANE Shop Till You Drop Corporate America cashes in on Armageddon.