Rambling Blues: Mapping Contemporary North American Blues Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Politics and Old and New Social Movements

P1: FHD/IVO/LCT P2: GCR/LCT QC: Qualitative Sociology [quso] ph132-quas-375999 June 13, 2002 19:33 Style file version June 4th, 2002 Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 25, No. 3, Fall 2002 (C 2002) Music in Movement: Cultural Politics and Old and New Social Movements Ron Eyerman1 After a period of interdisciplinary openness, contemporary sociology has only re- cently rediscovered culture. This is especially true of political sociology, where institutional and network analyses, as well as rational choice models, have dom- inated. This article will offer another approach by focusing on the role of music and the visual arts in relation to the formation of collective identity, collective memory and collective action. Drawing on my own research on the Civil Rights movement in the United States and the memory of slavery in the formation of African-American identity, and its opposite, the place of white power music in contemporary neo-fascist movements, I will outline a model of culture as more than a mobilization resource and of the arts as political mediators. KEY WORDS: social movements; representation; performance. COLLECTIVE BEHAVIOR: CULTURE AND POLITICS The study of collective behavior has traditionally included the study of sub- cultures and social movements as central elements. This was so from the beginning when the research field emerged in the disciplinary borderlands between sociology and psychology in the periods just before and after World War II. Using a scale of rationality, the collective behaviorist placed crowd behavior at the most irra- tional end of a continuum and social movements at the most rational. The middle ground was left for various cults and subcultures, including those identified with youth. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

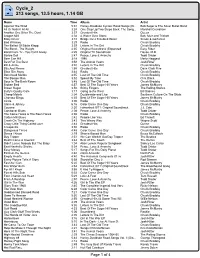

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

Bob Dylan Performs “It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009

Volume 19, Number 4, December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory A Foreign Sound to Your Ear: Bob Dylan Performs “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” 1964–2009 * Steven Rings NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.13.19.4/mto.13.19.4.rings.php KEYWORDS: Bob Dylan, performance, analysis, genre, improvisation, voice, schema, code ABSTRACT: This article presents a “longitudinal” study of Bob Dylan’s performances of the song “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” over a 45-year period, from 1964 until 2009. The song makes for a vivid case study in Dylanesque reinvention: over nearly 800 performances, Dylan has played it solo and with a band (acoustic and electric); in five different keys; in diverse meters and tempos; and in arrangements that index a dizzying array of genres (folk, blues, country, rockabilly, soul, arena rock, etc.). This is to say nothing of the countless performative inflections in each evening’s rendering, especially in Dylan’s singing, which varies widely as regards phrasing, rhythm, pitch, articulation, and timbre. How can music theorists engage analytically with such a moving target, and what insights into Dylan’s music and its meanings might such a study reveal? The present article proposes one set of answers to these questions. First, by deploying a range of analytical techniques—from spectrographic analysis to schema theory—it demonstrates that the analytical challenges raised by Dylan’s performances are not as insurmountable as they might at first appear, especially when approached with a strategic and flexible methodological pluralism. -

The History and Development of Jazz Piano : a New Perspective for Educators

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators. Billy Taylor University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Taylor, Billy, "The history and development of jazz piano : a new perspective for educators." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3017. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3017 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / DATE DUE .1111 i UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS LIBRARY LD 3234 ^/'267 1975 T247 THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation Presented By William E. Taylor Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfil Iment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF EDUCATION August 1975 Education in the Arts and Humanities (c) wnii aJ' THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO: A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS A Dissertation By William E. Taylor Approved as to style and content by: Dr. Mary H. Beaven, Chairperson of Committee Dr, Frederick Till is. Member Dr. Roland Wiggins, Member Dr. Louis Fischer, Acting Dean School of Education August 1975 . ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF JAZZ PIANO; A NEW PERSPECTIVE FOR EDUCATORS (AUGUST 1975) William E. Taylor, B.S. Virginia State College Directed by: Dr. -

The Future of Sea Mines in the Indo-Pacific

Issue 18, 2020 BREACHING THE SURFACE: THE FUTURE OF SEA MINES IN THE INDO-PACIFIC Alia Huberman, The Australian National Internships Program Issue 18, 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report argues that several dynamics of the coming few decades in the Indo-Pacific will see naval mines used once again in the region. It suggests they will form the basis of anti-access strategies for some Indo-Pacific states in a way that will be deeply transformative for the region’s strategic balance and for which Australia is thoroughly unprepared. It seeks to draw attention to the often- underappreciated nature of sea mines as a uniquely powerful strategic tool, offering the user an unparalleled asymmetric ability to engage high-value enemy targets while posing a minimal-risk, low- expense, and continuous threat. In the increasingly contested strategic environment of the contemporary Indo-Pacific - a region in which the threats to free navigation and the maritime economy are existential ones - there is considerable appetite for anti-access and sea denial weapons as defensive, offensive, and coercive tools. Naval strategists must,, prepare for the resurgence of mine warfare in the Indo-Pacific, and for the grand-scale and rapid timeline in which it can transform an operational environment. This report first seeks to collate and outline those characteristics of sea mines and of their interaction with an operational environment that make them attractive for use. It then discusses the states most likely to employ mine warfare and the different scenarios in which they might do so, presenting five individual contingencies: China, Taiwan, North Korea, non-state actors, and Southeast Asian states. -

Download Worlds of Music, Shorter Version 4Th Edition Free Ebook

WORLDS OF MUSIC, SHORTER VERSION 4TH EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Jeff Todd Titon | --- | --- | --- | 9781337517676 | --- | --- Worlds of Music, Shorter Version The four chapters in Part 6 now treat the past century in truly global terms, moving beyond a Cold War framework organized to consider the western capitalist world, the communist world, and the Third World of developing countries. In addition, the book incorporates the history of women as Worlds of Music and seamlessly as any general textbook I Shorter Version 4th edition seen. Sthaayi Antara Sanchaari Aabhog. Archived from the original on 6 May Worlds of Music The Record. Sims, W. The This shorter version of the best-selling WORLDS OF MUSIC is based on the 4th edition and provides much of the authoritative coverage of the comprehensive version in a format that's accessible to students without any background or training in music. Random House Publishers. He made his debut in the film Mandi directed by Shyam Benegal in It is mainly Shorter Version 4th edition by the Indian Zoroastrian community, Protestant Christian community in Chennai and Bangalore and small esoteric groups with historical exposure to Western classical music. Gurinder Kaur, a disciple of Kishori Amonkar. Shorter Version 4th edition, search, and highlight our Shorter Version 4th edition e-books. This is what we would expect. Where are the boundaries between Shorter Version 4th edition and music? Clarke, Trans. He is also well-known for his contribution to the compilation of Urdu-Persian dictionary along the new principles of Lexicography. Retrieved 21 July He has been a professor of Urdu at University of Hyderabad. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

Chlorine: the Achilles Heel?

Chlorine: the Achilles Heel? John McNabb Cohasset Water Commissioner Cohasset, Massachusetts Water Security Congress Washington DC, April 8-10, 2008 1 Cohasset Water Dept. • I have been an elected Water Commissioner in Cohasset, Mass. Since 1997. Just reelected to 5th term. • We serve about 7,000 residents, 2,500 accounts, 400 hydrants, 750 valves, 2 tanks, 1 wellfield, 2 reservoirs. Lily Pond Water Treatment Plant uses conventional filtration, fluoridation, and chlorination. • I am not an “expert” on water infrastructure security; this is more an essay than a formal analysis. • From 1999-Jan. 2009 I worked for Clean Water Action. • Now I work in IT security, where responsible disclosure of potential threats, not ‘security by obscurity” is the preferred method. 2 Cohasset – security measures • Vulnerability assessment as required • Fences & gates • Locks • Alarms, especially on storage tanks • Motion detectors • Video surveillance • Isolate SCADA from the internet • We think we’ve done everything that is reasonably necessary. 3 Water system interdependencies • But, the protection of our water system depends also on may factors outside of our control • The treatment chemicals we use is a critical factor. 4 Chlorine - Positives • Chlorination of drinking water is one of the top 5 engineering accomplishments of the modern age. • Chlorination of the US drinking water supply wiped out typhoid and cholera, and reduced the overall mortality rate in the US. 5 Chlorine - Negatives • Chlorine is very toxic, used as weapon in WWI. • Disinfection Byproducts (DPBs) • Occupational exposure on the job • Chlorine explosions on site at the plant • Terrorist use of chlorine as an explosive • Vector of attack? 6 Chlorine Explosions & Accidents • The Chlorine Institute estimates a chlorine tanker terrorist attack could release a toxic cloud up to 15 miles. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Short Synopsis a Young Woman Is

*** Please note: these production notes are for reference only and may contain spoilers. We would appreciate you not revealing the characters’ secrets in editorial or social postings without proper warning. The film is under embargo until Wednesday, February 21 at 10:30pm CET / 4:30pm EST / 1:30pm PST. Thank you. *** Short Synopsis A young woman is involuntarily committed to a mental institution where she is confronted by her greatest fear - but is it real or is it a product of her delusion? Long Synopsis Making a startling trip into thriller territory with Unsane, director Steven Soderbergh plunges audiences into the suspense and drama of a resilient woman’s (Claire Foy, The Crown) fight to reclaim her freedom even as she risks her own sanity. Scarred from the trauma of being stalked, quick-witted Sawyer Valentini (portrayed by Ms. Foy) has relocated from Boston to Pennsylvania for a new life. As her mother Angela (Academy Award nominee Amy Irving) misses her back home and her office job is hardly an ideal employment opportunity, Sawyer remains on edge following her two years of being terrorized. To consult with a therapist, she goes for follow-up treatment at the Highland Creek Behavioral Center. Sawyer’s initial therapy session at the suburban complex run by clinician Ashley Brighterhouse (Aimée Mullins, Stranger Things) progresses well — until she unwittingly signs herself in for voluntary 24-hour commitment. Unable to leave the premises, Sawyer finds herself in close quarters with previously committed hellion Violet (Juno Temple, The Dark Knight Rises) and savvy Nate (Jay Pharoah, Saturday Night Live), who is battling an opioid addiction.