Equipment for Post-Conflict Demining a Study Or Requirements in Mozambique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clearing the Mines

CLEARING THE MINES REPORT BY THE MINE ACTION TEAM FOR THE THIRD REVIEW CONFERENCE OF THE ANTIPERSONNEL MINE BAN TREATY June 2014 REPORT FOR THE THIRD REVIEW CONFERENCE OF THE ANTI-PERSONNEL MINE BAN TREATY CONTENTS Report for the Third Review Conference INTRODUCTION ANNEXES of the Antipersonnel Mine Ban Treaty ASSESSING 15 YEARS OF AFFECTED STATES NOT PARTY ARTICLE 5 IMPLEMENTATION 1 Armenia 158 2 Azerbaijan 162 Progress in mine clearance 05 3 China 165 The remaining challenge 08 4 Cuba 166 The architecture of an effective and 10 Armenia efficient mine action program 5 Egypt 167 Bosnia and Herzegovina 6 Georgia 168 Sudan 7 India 169 Turkey THE TEN MOST CONTAMINATED Tajikistan Somalia Russia STATES PARTIES 8 Iran 170 United Kingdom 9 Israel 174 1 Afghanistan 14 Yemen Iran South Sudan 10 Kyrgyzstan 176 2 Angola 20 Afghanistan 11 Lao PDR 177 3 Bosnia and Herzegovina 26 Croatia Serbia 12 Lebanon 178 * 4 Cambodia 32 13 Libya 182 5 Chad 38 14 Morocco 184 6 Croatia 40 15 Myanmar 186 7 Iraq 46 16 North Korea 188 8 Thailand 50 17 Pakistan 189 9 Turkey 56 China 18 Palestine 190 Angola 10 Zimbabwe 62 19 Russia 192 Myanmar Morocco 20 South Korea 194 OTHER AFFECTED STATES PARTIES 21 Sri Lanka 196 Ecuador Vietnam 22 Syria 200 1 Algeria 67 Chad Kosovo Cambodia 23 Uzbekistan 202 2 Argentina 71 Eritrea Iraq 24 Vietnam 203 Algeria 3 Chile 72 Peru Sri Lanka 4 Colombia 76 5 Cyprus 80 AFFECTED OTHER AREAS Chile Colombia Zimbabwe 6 Democratic Republic of the Congo 82 1 Kosovo 206 Mozambique Somaliland 7 Ecuador 86 2 Nagorno-Karabakh 208 Israel 8 Eritrea 90 -

Landmines, Detection, Explosives, Thermography, Temperature

Frontiers in Science 2013, 3(1): 27-42 DOI: 10.5923/j.fs.20130301.05 Literature Review on Landmines and Detection Methods Rasaq Bello Department of Physics Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria Abstract Detection of buried antipersonnel landmines (APL) is a demanding task in which one tries to obtain information about characteristics of the soil and of objects buried in it. Various methods that are used to detect buried landmines have been examined. None of these methods meets the standards that have been set by authorities such as the United Nations or the United States Army. Therefore there is an urgent need for new and improved methods to be developed, particularly in view of the threat that abandoned landmines pose to civilian populations. Various researches reviewed in this work showed thermography to be a good method to detect shallowly buried objects. Detection systems capable of quickly and accurately detecting buried landmines are the only possibility to significantly improve the demining process. Due to low signal-to-noise ratio, changing environment conditions that influence measurements and existence of other natural or man-made objects that give sensor readings similar to the landmine, interpretation of sensor data for landmine detection is a complicated task. Keywords Landmines, Detection, Explosives, Thermography, Temperature and as area-denial weapons. The latter use seeks to deny 1. Introduction access to large areas, since they are often unmarked and affect civilian populations after the cessation of military A land mine is a type of self-contained explosive device operations or hostilities. When used as a tactical barrier, they which is placed onto or into the ground, exploding when serve as deterrent to direct attack from or over a well defined triggered by a vehicle, a person, or an animal. -

Remote Explosive Scent Tracing REST

Remote Explosive Scent Tracing REST REMOTE EXPLOSIVE SCENT TRACING | REST NOVEMBER 2011 CONTENTS FOREWORD 6 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEW 7 > Challenges to the Morogoro REST project 12 > The current status of REST 15 CHAPTER 2 THE OLFACTORY SYSTEM AND OLFACTION: IMPLICATIONS FOR REST 19 > Introduction 20 > What every dog trainer should know about the olfactory system 20 > Genetics of olfaction 21 > What every dog trainer should know about olfactory perception 23 > The perception of mixes 24 > Salience and overshadowing 25 > Previous experience with odours 25 > Experience with components in mixtures 27 > What is the key odour for detecting an explosive 28 > Species specificity and configurational processing 30 > Changes in thresholds as a function of experience 31 > The role of odour intensity 32 > Masking 32 > Adaptation to odours 33 > Sniffing 34 > Afterthought: Olfactory enrichment, rats mice and dogs 35 > Summary 36 > Appendix: extra sections, maybe worth reading 37 > Species differences 37 > Problems with the combinatorial theory 38 > References 39 CHAPTER 3 ANALYTICAL AND PHYSICAL-CHEMISTRY OF EXPLOSIVES IN REST 45 > Introduction 46 > Chemical analysis of REST samples 48 > High performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) (US-Environmental Protection, EPA Method 8330) 49 > Gas chromatography (GC) with electron capture detector (ECD) (US-EPA Method 8095) 50 > GC with Nitrogen Phosphorus Detector (GC-NPD) 51 > GC mass spectrometry (GC-MS) 51 > REST sampling for detecting landmines 52 > Storage and presentation of dust REST samples 53 > Variables that influence the availability of detectable chemicals 54 > Background information 55 > Time lag after rain before the mine search can be resumed 56 > Soil type 56 > Vegetation 56 > Temperature 57 > Climate 57 > Locating mines 57 > Preparing training samples 57 > Summary and conclusions 58 > References 59 CHAPTER 4 STRATEGIES FOR THE RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTAL OF REST USING ANIMALS AS THE PRIMARY DETECTORS 61 > Introduction 62 > What is Applied Behaviour Analysis? 62 1. -

Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Daniele Ressler Center for International Stabilization and Recovery, [email protected]

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons CISR Studies and Reports CISR Resources 6-2009 Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Daniele Ressler Center for International Stabilization and Recovery, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-studiesreports Part of the Environmental Policy Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Ressler, Daniele, "Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines" (2009). CISR Studies and Reports. Paper 2. http://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-studiesreports/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CISR Resources at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CISR Studies and Reports by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Presented to United States Department of State Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement June 1, 2009 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .............................................................. 3 2. Introduction ....................................................................... 4 2.1. Background to the problem................................................. 4 2.2. Funding ........................................................................ 4 2.3. Project goal .................................................................. -

Landmines in Burma : The

IR /PS UNIVERSITYOF , Stacks CALIFORNIASANDIEGO W67 3 1822 02951 6960 V . 352 miGIC & DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE WORKING PAPER NO .352 LANDMINES IN BURMA : THE MILITARY DIMENSION Andrew Selth Working paper (Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre ) IR /PS Stacks AUST UC San Diego Received on : 03 - 29 -01 SDSC Working Papers Series Editor : Helen Hookey Published and distributed by : Strategic and Defence Studies Centre The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200 Australia Tel: 02 62438555 Fax : 02 62480816 , DIEGO UNIVERSITYOF CALIFORNIASAN 3 1822 02951 6960 INTE RELATIONSRÁCIFIC STUDIES LIBRARY , UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO LA JOLLA , CALIFORNIA 92093 WORKING PAPER NO . 352 LANDMINES IN BURMA : THE MILITARY DIMENSION Andrew Selth Canberra November 2000 National Library of Australia Cataloguing -in -Publication Entry Selth , Andrew , 1951 - . Landmines in Burma : themilitary dimension . Bibliography ISBN 0 7315 2779 8 ISSN 0158 - 3751 1. Insurgency - Burma . 2. Land mines - Burma . 3. Burma - Armed forces – Weapons systems . I. Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre . II. Title . (Series :Working paper (Australian NationalUniversity. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre ); no .352 ). 355.0332591 -01 , 3 © Andrew Selth 2000 4- ABSTRACT Since the signing of the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty in Ottawa , considerable attention has been given to the problem of uncleared landmines around the world and the thousands of casualties they cause each year. Yet , in all the literature produced on this subject to date , and discussions of the problem in various international forums , mention is rarely made of Burma. This is despite the fact that anti -personnel (AP ) landmines have been, and are still being,manufactured and laid in large numbers in that country , with serious consequences for both combatants and non - combatants alike . -

Mine Detection Dogs

Mine Detection Dogs Mine Detection Dogs Training, Operations and Odour Detection Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining 7bis, avenue de la Paix P.O. Box 1300 CH - 1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland Tel. (41 22) 906 16 60, Fax (41 22) 906 16 90 www.gichd.ch i Mine Detection Dogs: Training, Operations and Odour Detection ii Mine Detection Dogs: Training, Operations and Odour Detection The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) supports the efforts of the international community in reducing the impact of mines and unexploded ordnance. The Centre is active in research, provides operational assistance and supports the implementation of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention. For further information please contact: Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining 7bis, avenue de la Paix P.O. Box 1300 CH-1211 Geneva 1 Switzerland Tel. (41 22) 906 16 60 Fax (41 22) 906 16 90 www.gichd.ch [email protected] Mine Detection Dogs: Training, Operations and Odour Detection, GICHD, Geneva, 2003. This report was edited for the GICHD by Ian G. McLean, Mine Dog Specialist ([email protected]). ISBN 2-88487-007-5 © Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining The views expressed in this publication are those of the listed author(s) for each part, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities or armed groups, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Center for International Stabilization and Global CWD Repository Recovery 2009 Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Center for International Stabilization and Recovery CISR Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-globalcwd Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Recommended Citation and Recovery, Center for International Stabilization, "Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines" (2009). Global CWD Repository. 21. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-globalcwd/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global CWD Repository by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Scoping Study of the Effects of Aging on Landmines Presented to United States Department of State Office of Weapons Removal and Abatement June 1, 2009 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .............................................................. 3 2. Introduction ....................................................................... 4 2.1. Background to the problem................................................. 4 2.2. Funding ........................................................................ 4 2.3. Project goal .................................................................. -

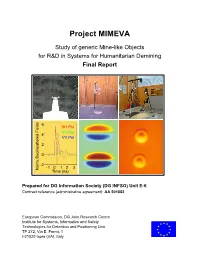

Project MIMEVA

Project MIMEVA Study of generic Mine-like Objects for R&D in Systems for Humanitarian Demining Final Report 6 HH Pol HV Pol 4 VV Pol 2 0 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 Norm. Backscattered Fields Backscattered Norm. Time (ns) Prepared for DG Information Society (DG INFSO) Unit E-6 Contract reference (administrative agreement): AA 501852 European Commission, DG Joint Research Centre Institute for Systems, Informatics and Safety Technologies for Detection and Positioning Unit TP 272, Via E. Fermi, 1 I-21020 Ispra (VA), Italy MIMEVA: Study of generic Mine-like Objects for R&D in Systems for Humanitarian Demining This final project report is based upon the contractually deliverable items listed below: D 1.2: Final List of mines for which Validation Tests will need to be Conducted with Advanced APL Detection Equipment D2.1:Report on the Available Methods for Replication of Landmines These documents, together with background text and supplementary information identified as relevant to the project have been edited together to form a coherent final report of the project. Compiled and edited by: John T. Dean, Ispra, July 2001 With contributions from: Joaquim Fortuny-Guasch Brian D. Hosgood Athina Kokonozi Adam M. Lewis Alois J. Sieber All experts are with the Unit TDP of the Institute of Systems Informatics and Safety, JRC, Ispra. MIMEVA: Study of generic Mine-like Objects for R&D in Systems for Humanitarian Demining Executive Summary The MIMEVA project aimed to assess available methods of production of mine simulants and surrogates in terms of the similarity of these replicas to real mines when viewed by a range of sensors identified most frequently as candidates for components in multi-sensor systems, namely: metal detectors, thermal infrared and a ground penetrating radar. -

Army Detector's Ability to Find Low-Metal Mines Not Clearly

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Ranking Minority Member, GAO House Committee on International Relations August 1996 MINE DETECTION Army Detector’s Ability to Find Low-Metal Mines Not Clearly Demonstrated GOA years 1921 - 1996 GAO/NSIAD-96-198 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-272391 August 28, 1996 The Honorable Lee H. Hamilton Ranking Minority Member Committee on International Relations House of Representatives Dear Mr. Hamilton: The dangers posed by over 80 million landmines emplaced worldwide are the subject of much discussion. You expressed concern over the threat of landmines to U.S. troops as they carry out their mission in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Landmines, especially those of low-metallic content, have been used extensively by all warring factions in the former Republic of Yugoslavia, and 5 to 7 million mines are estimated to be in the region. Between April 1992 and June 1995—prior to the deployment of U.S. troops to the former Republic—there were 174 landmine incidents involving U.N. Peacekeeping Forces, which included 204 casualties and 20 deaths. In response to your request, this report addresses (1) how the Army’s AN/PSS-12 portable mine detector performed in detecting low-metallic mines in tests conducted prior to procurement, (2) the nature of the landmine threat in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and (3) the AN/PSS-12’s potential effectiveness there. The military services use portable or handheld metal detectors as one of Background several devices to detect and clear hazards such as landmines. -

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Endnotes

Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction Volume 10 Issue 1 The Journal of Mine Action Article 47 August 2006 Endnotes CISR JOURNAL Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU (CISR) Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation JOURNAL, CISR (2006) "Endnotes," Journal of Mine Action : Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 47. Available at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/cisr-journal/vol10/iss1/47 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for International Stabilization and Recovery at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conventional Weapons Destruction by an authorized editor of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Endnotes JOURNAL: Endnotes An Alternative Perspective, Weitzel [ from page 10 ] Picking the Right Tool for the Right Task, Frehsee [ from page 21 ] 1. Gilbert Laurin, “Should the Ottawa Convention Banning Anti-personnel Landmines Be 1. USSR-manufactured stake mine with six rows of fragments. For more information, visit • Carrying out mechanical and/or manual pre-survey road treatments to reduce the Fully Implemented? Pro,” International Debates: Vol 2 (4), April 200, p. 112. http://www.eng.warwick.ac.uk/DTU/pubs/wp/wp48/appendixcminesandordinance. amount of loose scrap-metal on the road surface 2. We are also drawn to the issue by the impassioned pleas of high-profile celebrities such as html. -

Excavating Indications During Mine Clearance Two Proven Systems Are Explained Here, One Method Using Hand-Tools and the Other Using Rakes

Excavating indications during mine clearance Two proven systems are explained here, one method using hand-tools and the other using rakes. Both have safely exposed many thousands of mines and explosive devices. Excavating a metal-detector signal using hand-tools When a metal-detector signal has been pinpointed and a signal marker placed at the nearest part of the reading, the deminer can begin a signal-investigation procedure. If at any point during the procedure the source of the metal-detector indication is found and it was not a mine or ERW, the deminer should stop the investigation and return to the metal-detector search procedure, checking the area where the metal was found to see if there are other indications. If a mine or ERW is located, the deminer should expose the closest side of the device. Hand-tools used during signal excavation should be blast resistant and keep the user’s hand as far from the device as is practicable. 30cm has been proven effective in maintaining control of the tool while putting enough distance between the hand and an anti-personnel blast mine to prevent severe injury in most cases. The picture above shows some blast resistant hand-tools. Any tool that is used in the ground during signal excavation should be blast-resistant to prevent them separating or fragmenting in an anti-personnel mine blast. Tools designed for gardeners may only be used for vegetation cutting. Magnets Strong magnets can be very useful in areas where metal-detector search is used and there is a lot of metal contamination in the ground. -

Hyperspectral Imaging for Landmine Detection Ihab Makki

Hyperspectral Imaging for Landmine Detection Ihab Makki To cite this version: Ihab Makki. Hyperspectral Imaging for Landmine Detection. Optimization and Control [math.OC]. POLITECNICO DI TORINO, 2017. English. tel-01706356 HAL Id: tel-01706356 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01706356 Submitted on 11 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PhD Thesis Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the PhD degree from LEBANESE UNIVERSITY AND POLITECNICO DI TORINO Major: Electrical and Electronics Engineering Presented and defended by: Makki Ihab 12 Decembre 2017 Hyperspectral Imaging for Landmine Detection Supervised by: Prof. Rafic Younes Prof. Clovis Francis Prof. Tiziano Bianchi Prof. Massimo Zucchetti Members of the Jury: Mme Maria Sabrina Greco, Prof, University of Pisa, Reviewer M. Ali El-Zaart,Prof, Beirut Arab University Reviewer Mme Luisa Verdoliva, Dr, University of Naples Federico II Examiner M. Georges Sakr, Dr, University Saint Joseph Examiner M. Rafic Younes, Prof, Lebanese University Director M. Clovis Francis, Prof, Lebanese University Co-Director M. Massimo Zucchetti, Prof, Politecnico di Torino Director M. Tiziano Bianchi, Dr, Politecnico di Torino Co-Director M. Abdallah Fahed, Prof, Lebanese University Invited M.