UNITED STATES-PAKISTAN RELATIONS: Facing a Critical Juncture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Pakistanonedge.Pdf

Pakistan Project Report April 2013 Pakistan on the Edge Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013 Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in ISBN: 978-93-82512-02-8 First Published: April 2013 Cover shows Data Ganj Baksh, popularly known as Data Durbar, a Sufi shrine in Lahore. It is the tomb of Syed Abul Hassan Bin Usman Bin Ali Al-Hajweri. The shrine was attacked by radical elements in July 2010. The photograph was taken in August 2010. Courtesy: Smruti S Pattanaik. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. Published by: Magnum Books Pvt Ltd Registered Office: C-27-B, Gangotri Enclave Alaknanda, New Delhi-110 019 Tel.: +91-11-42143062, +91-9811097054 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.magnumbooks.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). Contents Preface 5 Abbreviations 7 Introduction 9 Chapter 1 Political Scenario: The Emerging Trends Amit Julka, Ashok K. Behuria and Sushant Sareen 13 Chapter 2 Provinces: A Strained Federation Sushant Sareen and Ashok K. Behuria 29 Chapter 3 Militant Groups in Pakistan: New Coalition, Old Politics Amit Julka and Shamshad Ahmad Khan 41 Chapter 4 Continuing Religious Radicalism and Ever Widening Sectarian Divide P. -

Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank

Vol. XIII, Issue III - ISSN 2305-7947 Winter Semester 2013-2014 A Quarterly Periodical of Greenwich Earns the Most Exculsive Awards Banking Future Lies in Islamic Banking Muhammad Raza Head of Consumer Banking & Marketing Meezan Bank “Smart Thinking Can Lead To Success” Karim Ismail Teli Director, Orient Textile & Ibrahim Group of Companies Greenwich Alumnus Dear Readers, It gives us immense pleasure and joy to see G.Vision take its final shape at the com - pletion of another successful semester: Winter 2013-14.We can look at it and say that it’s an accomplished piece of work. This issue of G-Vision highlights an environ - ment of innovation and several significant events around Greenwich campus as we continue to evolve and grow. It is indeed a matter of great pride to be the editor of an issue where the cover story is all about the unwavering efforts, hard work and dedication of our Vice Chancel - lor and her entire team. Our cover story shines with Greenwich being the first ever EDITORIAL BOARD HEC recognized university to achieve the most prestigious awards namely The Brand of the Year Award and The Brand Scientist Award. Patron It is best said that “life is a succession of lessons which must be lived to be under - stood”. Life is an informal school. Each day we have an opportunity to learn. In this Ms Seema Mughal process of trial and error emerges the process of growth. Vice Chancellor Keeping this in mind I believe we have succeeded in putting together a well- Editor rounded, enjoyable memento for everybody. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Pakistan Security Situation October 2018 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-319-8 doi: 10.2847/639900 © European Asylum Support Office 2018 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: FATA Faces FATA Voices, © FATA Reforms, url, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT PAKISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the Belgian Center for Documentation and Research (Cedoca) in the Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, as the drafter of this report. Furthermore, the following national asylum and migration departments have contributed by reviewing the report: The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis Hungary, Office of Immigration and Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Office Documentation Centre Slovakia, Migration Office, Department of Documentation and Foreign Cooperation Sweden, Migration Agency, Lifos -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards - 14Th August, 2020

F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14TH AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following ‘Pakistan Civil Awards’ on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2021:- S. No. Name of Awardee Field 1 2 3 I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-QUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA’AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 20 Mr. -

Operation Zarb-E-Azb: a Success Story of Pakistan Military Forces in FATA

Vol. 5(3), pp. 105-113, May 2017 DOI: 10.14662/IJPSD2017.016 International Journal of Copy©right 2017 Political Science and Author(s) retain the copyright of this article ISSN: 2360-784X Development http://www.academicresearchjournals.org/IJPSD/Index.html Full Length Research Operation Zarb-e-Azb: A Success Story of Pakistan Military Forces in FATA Muhammad Hamza Scholar of M. Phil Pakistan Studies, Al-Khair University, Azad Jammu & Kashmir, Bhimber. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted 15 May 2017 Federal Administered Tribal Area (FATA) considered a backward area of Pakistan. The residents of FATA were against western culture and education before military operation Zarb-e-Azb (Zeb). Unemployment made a big cause for the terrorism culture in this area. Local terrorist groups like as Tahrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, Haqqani Network and some groups of Al-Qaida forced the residents for waging war against Pakistan military forces. FATA was the heavenly place for the shelter of terrorists after 9/11 incident. After military Operation Zeb, Terrorism has decreased than the last three years. Military forces have successfully restored the writ of the state and numbers of terrorists and their facilitators killed and arrested in this operation. The aim of this study is finding the role of Pakistan military forces for the restoration of the writ of State after operation Zarb-e-Azb in FATA. This study will also show the effects of terrorism on the residents of FATA. During this research, it was found that Federal government failed for the provision of basic needs of the residents of FATA. -

Islamist Militancy in the Pakistan-Afghanistan Border Region and U.S. Policy

= 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38 +,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= _=1&3=74389&)9= 5*(.&1.89=.3=4:9-=8.&3=++&.78= *33*9-=&9?2&3= 5*(.&1.89=.3=.))1*=&89*73=++&.78= 4;*2'*7=,+`=,**2= 43,7*88.43&1= *8*&7(-=*7;.(*= 18/1**= <<<_(78_,4;= -.10-= =*5479=+47=43,7*88 Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress 81&2.89= .1.9&3(>=.3=9-*=&0.89&38+,-&3.89&3=47)*7=*,.43=&3)=__=41.(>= = :22&7>= Increasing militant activity in western Pakistan poses three key national security threats: an increased potential for major attacks against the United States itself; a growing threat to Pakistani stability; and a hindrance of U.S. efforts to stabilize Afghanistan. This report will be updated as events warrant. A U.S.-Pakistan relationship marked by periods of both cooperation and discord was transformed by the September 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States and the ensuing enlistment of Pakistan as a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. Top U.S. officials have praised Pakistan for its ongoing cooperation, although long-held doubts exist about Islamabad’s commitment to some core U.S. interests. Pakistan is identified as a base for terrorist groups and their supporters operating in Kashmir, India, and Afghanistan. Since 2003, Pakistan’s army has conducted unprecedented and largely ineffectual counterterrorism operations in the country’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) bordering Afghanistan, where Al Qaeda operatives and pro-Taliban insurgents are said to enjoy “safe haven.” Militant groups have only grown stronger and more aggressive in 2008. -

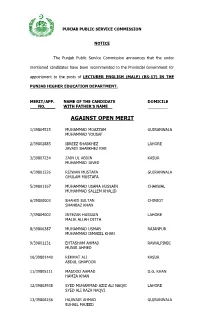

Against Open Merit

PUNJAB PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION NOTICE The Punjab Public Service Commission announces that the under mentioned candidates have been recommended to the Provincial Government for appointment to the posts of LECTURER ENGLISH (MALE) (BS-17) IN THE PUNJAB HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT. MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ AGAINST OPEN MERIT 1/39804515 MUHAMMAD MOAZZAM GUJRANWALA MUHAMMAD YOUSAF 2/39802885 IBREEZ SHABKHEZ LAHORE JAVAID SHABKHEZ RAB 3/39807234 ZAIN UL ABDIN KASUR MUHAMMAD JAVED 4/39801226 RIZWAN MUSTAFA GUJRANWALA GHULAM MUSTAFA 5/39801167 MUHAMMAD USAMA HUSSAIN CHAKWAL MUHAMMAD SALLEM KHALID 6/39800003 SHAHID SULTAN CHINIOT SHAHBAZ KHAN 7/39804002 INTEZAR HUSSAIN LAHORE MALIK ALLAH DITTA 8/39806387 MUHAMMAD USMAN RAJANPUR MUHAMMAD ISMAEEL KHAN 9/39801131 EHTASHAM AHMAD RAWALPINDI MUNIR AHMED 10/39801440 REHMAT ALI KASUR ABDUL GHAFOOR 11/39805111 MASOOD AHMAD D.G. KHAN HAMZA KHAN 12/39803938 SYED MUHAMMAD AZIZ ALI NAQVI LAHORE SYED ALI RAZA NAQVI 13/39808156 HAJWAIR AHMAD GUJRANWALA SUHAIL MAJEED 130 posts of Lecturer English (Male) (BS-17) in the Punjab Higher Education Department MERIT/APP. NAME OF THE CANDIDATE DOMICILE NO.____ WITH FATHER'S NAME ________ 14/39801309 MUHAMMAD RIAZ VEHARI MUHAMMAD AMIN 15/39806076 MUHAMMAD IMTIAZ SHAHID SARGODHA MUHAMMAD ASLAM BHATTI 16/39808459 TALAT HUSSAIN SARGODHA KHALID MEHMOOD 17/39806351 NABEEL AHMED MINHAS FAISALABAD IJAZ AHMED 18/39800666 MUHAMMAD AHSAN T.T. SINGH MUHAMMAD IRSHAD 19/39803437 MUHAMMAD ABDULLAH VEHARI ABDUL JABBAR 20/39801419 IRFAN KHALID M.B.DIN KHALID PERVAIZ 21/39803560 JAN SHER KHAN RAJANPUR MUHAMMAD ISHAQ 22/39802060 MOHIODIN FARHAN FAISALABAD UMER HAYAT 23/39802642 MUHAMMAD REHAN MULTAN MUHAMMAD ISLAM 24/39800428 MUHAMMAD AMEER KHAN KHUSHAB NASEER AHMAD 25/39802577 MUHAMMAD FAHAD SALEEM M. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 494 | MAY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan By Amira Jadoon Contents Introduction ...................................3 The Rise and Decline of the TTP, 2007–18 .....................4 Signs of a Resurgent TPP, 2019–Early 2021 ............... 12 Regional Alliances and Rivalries ................................ 15 Conclusion: Keeping the TTP at Bay ............................. 19 A Pakistani soldier surveys what used to be the headquarters of Baitullah Mehsud, the TTP leader who was killed in March 2010. (Photo by Pir Zubair Shah/New York Times) Summary • Established in 2007, the Tehrik-i- attempts to intimidate local pop- regional affiliates of al-Qaeda and Taliban Pakistan (TTP) became ulations, and mergers with prior the Islamic State. one of Pakistan’s deadliest militant splinter groups suggest that the • Thwarting the chances of the TTP’s organizations, notorious for its bru- TTP is attempting to revive itself. revival requires a multidimensional tal attacks against civilians and the • Multiple factors may facilitate this approach that goes beyond kinetic Pakistani state. By 2015, a US drone ambition. These include the Afghan operations and renders the group’s campaign and Pakistani military Taliban’s potential political ascend- message irrelevant. Efforts need to operations had destroyed much of ency in a post–peace agreement prioritize investment in countering the TTP’s organizational coherence Afghanistan, which may enable violent extremism programs, en- and capacity. the TTP to redeploy its resources hancing the rule of law and access • While the TTP’s lethality remains within Pakistan, and the potential to essential public goods, and cre- low, a recent uptick in the number for TTP to deepen its links with ating mechanisms to address legiti- of its attacks, propaganda releases, other militant groups such as the mate grievances peacefully. -

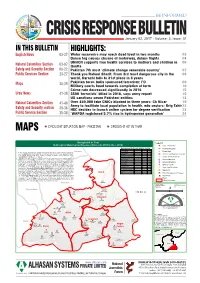

Crisis Response Bulletin V3I1.Pdf

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN January 02, 2017 - Volume: 3, Issue: 01 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-27 Water reservoirs may reach dead level in two months 03 Dense fog causes closure of motorway, delays flights 04 UNHCR supports free health services to mothers and children in 06 Natural Calamities Section 03-07 Quetta Safety and Security Section 08-22 Pakistan 7th most ‘climate change venerable country’ 07 Public Services Section 23-27 Thank you Raheel Sharif: From 3rd most dangerous city in the 08 world, Karachi falls to 31st place in 3 years Maps 28-29 Pakistan faces India sponsored terrorism: FO 09 Military courts head towards completion of term 10 Crime rate decreased significantly in 2016 15 Urdu News 41-30 3500 ‘terrorists’ killed in 2016, says army report 15 US sanctions seven Pakistani entities 18 Natural Calamities Section 41-40 Over 450,000 fake CNICs blocked in three years: Ch Nisar 19 Army to facilitate local population in health, edu sectors: Brig Tahir23 Safety and Security section 39-36 HEC decides to launch online system for degree verification 23 Public Service Section 35-30 ‘WAPDA registered 5.7% rise in hydropower generation’ 24 MAPS DROUGHT SITUATION MAP - PAKISTAN DROUGHT HIT IN THAR Drought Hit in Thar Legend Outbreak of Waterborne Diseases (from Jan,2016 to Dec, 2016) G Basic Health Unit Government & Private Health Facility ÷Ó Children Hospital Health Facility Government Private Total Sanghar Basic Health Unit 21 0 21 G Dispensary At least nine more infants died due to malnutrition and outbreak of the various diseases in Thar during that last two Children Hospital 0 1 1 days, raising the toll to 476 this year.With the death of nine more children the toll rose to 476 during past 12 months Dispensary 12 0 12 "' District Headquarter Hospital of the outgoing year, said health officials. -

Tehrik-E-Taliban Pakistan

DIIS REPORT 2010:12 DIIS REPORT TEHRIK-E-TALIBAN PAKISTAN AN ATTEMPT TO DECONSTRUCT THE UMBRELLA ORGANIZATION AND THE REASONS FOR ITS GROWTH IN PAKISTAN’S NORTH-WEST Qandeel Siddique DIIS REPORT 2010:12 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2010:12 © Copenhagen 2010, Qandeel Siddique and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Pakistani Taliban chief Hakimullah Mehsud promising future attacks on major U.S. cities and claiming responsibility for the attempted car bombing on Times Square, New York (AP Photo/IntelCenter) Cover: Anine Kristensen Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-419-9 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Qandeel Siddique, MSc, Research Assistant, DIIS www.diis.dk/qsi 2 DIIS REPORT 2010:12 Contents Executive Summary 4 Acronyms 6 1. TTP Organization 7 2. TTP Background 14 3. TTP Ideology 20 4. Militant Map 29 4.1 The Waziristans 30 4.2 Bajaur 35 4.3 Mohmand Agency 36 4.4 Middle Agencies: Kurram, Khyber and Orakzai 36 4.5 Swat valley and Darra Adamkhel 39 4.6 Punjab and Sind 43 5. Child Recruitment, Media Propaganda 45 6. Financial Sources 52 7. Reasons for TTP Support and FATA and Swat 57 8. Conclusion 69 Appendix A. -

Taleban Leader Baitullah Mehsud Dead: Is It the Beginning of the End of Terrorism?

ISA S Brief No. 122– Date: 11 August 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Taleban Leader Baitullah Mehsud Dead: Is it the Beginning of the End of Terrorism? Ishtiaq Ahmed1 Abstract The reported death of the Pakistan Taleban leader, Baitullah Mehsud, is a major development in the ongoing struggle against terrorism. It undoubtedly carries crucial implications not only for peace and normalcy in Pakistan, but also in South Asia and indeed the wider world. This brief contextualises the events leading up to his death on 5 August 2009. It is suggested that Pakistan should not relent now. It is in Pakistan’s best interest to dismantle the terrorist networks that still exist in its territory, notwithstanding the formal ban on them. Introduction Taleban leader, Baitullah Mehsud, who was behind scores of terrorist attacks in Pakistan reportedly died on 5 August 2009 after a United States’ drone fired missiles at the house of his father-in-law in South Waziristan, where Mehsud was visiting. Pakistan Foreign Minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, could be seen on television manifestly pleased with the outcome of the attack. It may be recalled that, in recent months, Mehsud was being portrayed as Pakistan’s “Enemy Number One”. Conspiracy theories denounced him as a paid agent of the United States’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and India’s Research and Analysis Wing. However, his death, as a result of missiles fired by an American drone, suggests closer relations between the CIA and Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence and the military because without the sharing of intelligence between them, such an operation would not have been possible. -

The Battle for Pakistan

ebooksall.com ebooksall.com ebooksall.com SHUJA NAWAZ THE BATTLE F OR PAKISTAN The Bitter US Friendship and a Tough Neighbourhood PENGUIN BOOKS ebooksall.com Contents Important Milestones 2007–19 Abbreviations and Acronyms Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Footnotes Important Milestones 2007–19 Preface: Salvaging a Misalliance 1. The Revenge of Democracy? 2. Friends or Frenemies? 3. 2011: A Most Horrible Year! 4. From Tora Bora to Pathan Gali 5. Internal Battles 6. Salala: Anatomy of a Failed Alliance 7. Mismanaging the Civil–Military Relationship 8. US Aid: Leverage or a Trap? 9. Mil-to-Mil Relations: Do More 10. Standing in the Right Corner 11. Transforming the Pakistan Army 12. Pakistan’s Military Dilemma 13. Choices Select Bibliography ebooksall.com Acknowledgements Follow Penguin Copyright ebooksall.com Advance Praise for the Book ‘An intriguing, comprehensive and compassionate analysis of the dysfunctional relationship between the United States and Pakistan by the premier expert on the Pakistan Army. Shuja Nawaz exposes the misconceptions and contradictions on both sides of one of the most crucial bilateral relations in the world’ —BRUCE RIEDEL, senior fellow and director of the Brookings Intelligence Project, and author of Deadly Embrace: Pakistan, America and the Future of the Global Jihad ‘A superb, thoroughly researched account of the complex dynamics that have defined the internal and external realities of Pakistan over the past dozen years.