The Anglophone Toponyms Associated with John Smith's <I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View 2019 Edition Online

Emmanuel Emmanuel College College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 Front Court, engraved by R B Harraden, 1824 VOL CI MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI Emmanuel College St Andrew’s Street Cambridge CB2 3AP Telephone +44 (0)1223 334200 The Master, Dame Fiona Reynolds, in the new portrait by Alastair Adams May Ball poster 1980 THE YEAR IN REVIEW I Emmanuel College MAGAZINE 2018–2019 VOLUME CI II EMMANUEL COLLEGE MAGAZINE 2018–2019 The Magazine is published annually, each issue recording college activities during the preceding academical year. It is circulated to all members of the college, past and present. Copy for the next issue should be sent to the Editors before 30 June 2020. News about members of Emmanuel or changes of address should be emailed to [email protected], or via the ‘Keeping in Touch’ form: https://www.emma.cam.ac.uk/members/keepintouch. College enquiries should be sent to [email protected] or addressed to the Development Office, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. General correspondence concerning the Magazine should be addressed to the General Editor, College Magazine, Dr Lawrence Klein, Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. Correspondence relating to obituaries should be addressed to the Obituaries Editor (The Dean, The Revd Jeremy Caddick), Emmanuel College, Cambridge CB2 3AP. The college telephone number is 01223 334200, and the email address is [email protected]. If possible, photographs to accompany obituaries and other contributions should be high-resolution scans or original photos in jpeg format. The Editors would like to express their thanks to the many people who have contributed to this issue, with a special nod to the unstinting assistance of the College Archivist. -

Choral Evensong with the the Installation of the Revd Rosie Austin the Revd James Grier and the Revd Deborah Parsons As Prebendaries

Choral Evensong with the The Installation of The Revd Rosie Austin The Revd James Grier and The Revd Deborah Parsons as Prebendaries Sunday 11 October 2020 4pm The Eighteenth Sunday after Trinity Robert Bishop of Exeter Welcome to the Cathedral We at Exeter Cathedral are delighted to host this service of installation for Rosie Austin, James Grier and Deborah Parsons. We welcome them and their families. As members of the College of Canons, they will contribute to the life of the Cathedral and its governance, and promote the mission and service of the Church in the Diocese. As members of the College of Canons, they receive the Cathedral’s annual report and accounts, discuss matters concerning the Cathedral, and give advice or counsel as requested by the Bishop or Chapter. The Cathedral Church of St. Peter in Exeter, founded in 1050, has been the seat (cathedra) of the bishop of Exeter, the symbol of his spiritual and teaching authority, for nearly 1000 years. As such the Cathedral is a centre of worship and mission for the whole of Devon. A centuries-old pattern of daily worship continues, sustained by the best of the Anglican choral tradition. The cathedral is a place of outreach, learning, and spirituality, inviting people into a richer and more engaged discipleship. The Cathedral is a destination for many pilgrims and visitors who come from near and far, drawn by the physical and spiritual heritage of this place. Exeter Cathedral belongs to all the people of Devon, and we warmly welcome you here. COVID-19: Infection Control Face Coverings in the cathedral As of 8 August 2020, wearing face coverings in places of worship is now mandatory. -

Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research

Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research Gisela Eberhardt Fabian Link (eds.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD has become increasingly diverse in recent years due to developments in the historiography of the sciences and the human- ities. A move away from hagiography and presentations of scientifi c processes as an inevitable progression has been requested in this context. Historians of archae- olo gy have begun to utilize approved and new histo- rio graphical concepts to trace how archaeological knowledge has been acquired as well as to refl ect on the historical conditions and contexts in which knowledge has been generated. This volume seeks to contribute to this trend. By linking theories and models with case studies from the nineteenth and twentieth century, the authors illuminate implications of communication on archaeological knowledge and scrutinize routines of early archaeological practices. The usefulness of di erent approaches such as narratological concepts or the concepts of habitus is thus considered. berlin studies of 32 the ancient world berlin studies of the ancient world · 32 edited by topoi excellence cluster Historiographical Approaches to Past Archaeological Research edited by Gisela Eberhardt Fabian Link Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. © 2015 Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Typographic concept and cover design: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN 978-3-9816384-1-7 URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:11-100233492 First published 2015 The text of this publication is licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC 3.0 DE. -

The Transport System of Medieval England and Wales

THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM OF MEDIEVAL ENGLAND AND WALES - A GEOGRAPHICAL SYNTHESIS by James Frederick Edwards M.Sc., Dip.Eng.,C.Eng.,M.I.Mech.E., LRCATS A Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Salford Department of Geography 1987 1. CONTENTS Page, List of Tables iv List of Figures A Note on References Acknowledgements ix Abstract xi PART ONE INTRODUCTION 1 Chapter One: Setting Out 2 Chapter Two: Previous Research 11 PART TWO THE MEDIEVAL ROAD NETWORK 28 Introduction 29 Chapter Three: Cartographic Evidence 31 Chapter Four: The Evidence of Royal Itineraries 47 Chapter Five: Premonstratensian Itineraries from 62 Titchfield Abbey Chapter Six: The Significance of the Titchfield 74 Abbey Itineraries Chapter Seven: Some Further Evidence 89 Chapter Eight: The Basic Medieval Road Network 99 Conclusions 11? Page PART THREE THr NAVIGABLE MEDIEVAL WATERWAYS 115 Introduction 116 Chapter Hine: The Rivers of Horth-Fastern England 122 Chapter Ten: The Rivers of Yorkshire 142 Chapter Eleven: The Trent and the other Rivers of 180 Central Eastern England Chapter Twelve: The Rivers of the Fens 212 Chapter Thirteen: The Rivers of the Coast of East Anglia 238 Chapter Fourteen: The River Thames and Its Tributaries 265 Chapter Fifteen: The Rivers of the South Coast of England 298 Chapter Sixteen: The Rivers of South-Western England 315 Chapter Seventeen: The River Severn and Its Tributaries 330 Chapter Eighteen: The Rivers of Wales 348 Chapter Nineteen: The Rivers of North-Western England 362 Chapter Twenty: The Navigable Rivers of -

Schuler Dissertation Final Document

COUNSEL, POLITICAL RHETORIC, AND THE CHRONICLE HISTORY PLAY: REPRESENTING COUNCILIAR RULE, 1588-1603 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Anne-Marie E. Schuler, B.M., M.A. Graduate Program in English The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Dutton, Advisor Professor Luke Wilson Professor Alan B. Farmer Professor Jennifer Higginbotham Copyright by Anne-Marie E. Schuler 2011 ABSTRACT This dissertation advances an account of how the genre of the chronicle history play enacts conciliar rule, by reflecting Renaissance models of counsel that predominated in Tudor political theory. As the texts of Renaissance political theorists and pamphleteers demonstrate, writers did not believe that kings and queens ruled by themselves, but that counsel was required to ensure that the monarch ruled virtuously and kept ties to the actual conditions of the people. Yet, within these writings, counsel was not a singular concept, and the work of historians such as John Guy, Patrick Collinson, and Ann McLaren shows that “counsel” referred to numerous paradigms and traditions. These theories of counsel were influenced by a variety of intellectual movements including humanist-classical formulations of monarchy, constitutionalism, and constructions of a “mixed monarchy” or a corporate body politic. Because the rhetoric of counsel was embedded in the language that men and women used to discuss politics, I argue that the plays perform a kind of cultural work, usually reserved for literature, that reflects, heightens, and critiques political life and the issues surrounding conceptions of conciliar rule. -

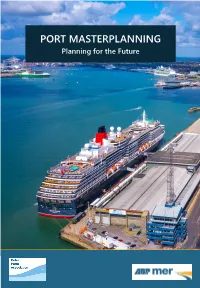

PORT MASTERPLANNING Planning for the Future Port of Ipswich (Source: ABP)

PORT MASTERPLANNING Planning for the Future Port of Ipswich (Source: ABP) This White Paper is part of Port Futures, a thought leadership platform for British Ports Association (BPA) members and the wider industry. The programme addresses key issues for ports, including technology, infrastructure and skills, as well as opportunities for and challenges to British ports that these issues present. ABPmer has extensive experience helping develop port masterplans for Associated British Ports’ facilities across the UK, many akin to the diverse range of ports within the BPA’s membership and throughout the UK. What is port masterplanning? At its core, a port masterplan will nearly always include a map, setting out the physical extent Port masterplanning deals directly with two of of plans for change. The map should result the most challenging issues facing the ports from a detailed process of strategic thinking industry: that delivers the best possible contribution to commercial growth, the local economy, and the 1. Understanding the nature of the very rapid local environment whilst working with a commercial, environmental, technical and practical understanding of the risks and social changes that are going to hit constraints facing the port. At the same time, it economies over the coming decades. should also deliver a set of investments over the short, medium and long term. 2. Responding appropriately to such changes. For the ports industry, these present big By their nature, ports are at the challenges and exciting opportunities. interface of land and sea, making Successful ports will be those which make the them unique places to masterplan. most coherent infrastructure and property _________________________________________________________________ investment. -

Great War Memorial Window

St James the Less Parish Church West Teignmouth Great War Memorial Window - 2 - Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Preface......................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction................................................................................................................................. 7 From the Teignmouth Post 1920................................................................................................. 8 THE FALLEN (1914-1918) ..................................................................................................... 13 Some Individual Accounts........................................................................................................ 25 William Barge of Teignmouth (O/N J124(Dev)).................................................................. 25 The Hamlyn Family.............................................................................................................. 27 The West Family in 1915...................................................................................................... 28 Charles Young ...................................................................................................................... 30 100 years on - Memorial Service 2014..................................................................................... 31 The Memorial -

IPSWICH Road, Rail and Sea Connectivity to LET Close Proximity to Ipswich City Warehousing / Open Storage Land / Centre, the A14 and A12 Design & Build Opportunities

IPSWICH Road, rail and sea connectivity TO LET Close proximity to Ipswich city Warehousing / Open Storage Land / centre, the A14 and A12 Design & Build Opportunities Ipswich, IP2 8NB Range of opportunities available Available Property Delivering Property Solutions Ipswich, Available Property Boston A16 A148 Opportunity A52 A17 A1065 A151 A148 The Port provides multimodal facilities, including 1,800m of berths and Spalding A140 A17 King's Lynn A1175 Sat Nav: IP2 8NB a direct rail connection. ABP Ports A47 Norwich A1101 A10 Dereham A47 A47 Airport Swaffham Norwich ABP has invested significantly in the port over the past few years, modernising Wisbech A47 Downham Great Yarmouth Market A15 A47 infrastructure to supply customers with specialist storage solutions and handling A1122 A146 A12 A134 equipment. Existing occupiers on the Port include Tarmac, Brett Aggregates, March A11 A1117 A141 Lowestoft Cofco International, and Clarkson Port Services. A1065 A140 A146 A143 A10 Thetford A142 A1066 A1(M) Ely A11 A142 Mildenhall A143 M11 A12 Location Port Services A10 St Ives A140 Bury A14 A14 St Edmunds The Port of Ipswich is strategically situated at the head The Port handles 2.0 million tonnes of goods annuallyA1 J14 67m Newmarket A14 St Neots A428 of the River Orwell, 12 miles from the open sea and and has expertise in the handling of steel, forest A134 Cambridge Stowmarket within a short sailing time from the North Sea shipping products and bulk cargoes. A11 A14 lanes. The port also has an active rail line on the West A12 A10 The docks can accept vessels of varying sizes: M11 Ipswich Bank Terminal. -

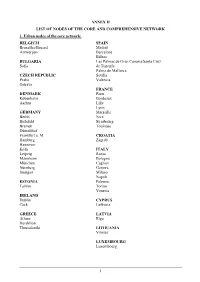

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern

CONNECTED HISTORIES IN THE EARLY MODERN WORLD Das, Melo, SmithDas, & Working Melo, in Early Modern England Modern Early in Mobility Human and Race, Identity, of Keywords Nandini Das, João Vicente Melo, Haig Z. Smith, and Lauren Working Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England Keywords of Identity, Race, and Human Mobility in Early Modern England Connected Histories in the Early Modern World Connected Histories in the Early Modern World contributes to our growing understanding of the connectedness of the world during a period in history when an unprecedented number of people—Africans, Asians, Americans, and Europeans—made transoceanic or other long distance journeys. Inspired by Sanjay Subrahmanyam’s innovative approach to early modern historical scholarship, it explores topics that highlight the cultural impact of the movement of people, animals, and objects at a global scale. The series editors welcome proposals for monographs and collections of essays in English from literary critics, art historians, and cultural historians that address the changes and cross-fertilizations of cultural practices of specific societies. General topics may concern, among other possibilities: cultural confluences, objects in motion, appropriations of material cultures, cross-cultural exoticization, transcultural identities, religious practices, translations and mistranslations, cultural impacts of trade, discourses of dislocation, globalism in literary/visual arts, and cultural histories of lesser studied regions (such as the -

The Spanish Match and Jacobean Political Thought, 1618-1624

Opposition in a pre-Republican Age? The Spanish Match and Jacobean Political Thought, 1618-1624 Kimberley Jayne Hackett Ph.D University of York History Department July 2009 Abstract Seventeenth-century English political thought was once viewed as insular and bound by a common law mentality. Significant work has been done to revise this picture and highlight the role played by continental religious resistance theory and what has been termed 'classical republicanism'. In addition to identifying these wider influences, recent work has focused upon the development of a public sphere that reveals a more socially diverse engagement with politics, authority and opposition than has hitherto been acknowledged. Yet for the period before the Civil War our understanding of the way that several intellectual influences were interacting to inform a politically alert 'public' is unclear, and expressions of political opposition are often tied to a pre-determined category of religious affiliation. As religious tension erupted into conflict on the continent, James I's pursuit ofa Spanish bride for Prince Charles and determination to follow a diplomatic solution to the war put his policy direction at odds with a dominant swathe of public opinion. During the last years of his reign, therefore, James experienced an unprecedented amount of opposition to his government of England. This opposition was articulated through a variety of media, and began to raise questions beyond the conduct of policy in addressing fundamental issues of political authority. By examining the deployment of political ideas during the domestic crisis of the early 1620s, this thesis seeks to uncover the varied ways in which differing discourses upon authority and obedience were being articulated against royal government. -

Enabling Growth in the New Anglia Ports & Logistics Sector Through

Enabling Growth in the New Anglia Ports & Logistics Sector through Skills Development 2018-‘25 A Skills Plan for New Anglia March 2018 Putting skills at the heart of building a competitive and sustainable local economy ports and logistics final plan post skills board 2018.docx Page 2 New Anglia LEP Ports and Logistics Sector Skills Plan, March 2018 Contents Background Context ............................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 Overview and Sector Definition of the Ports and Logistics Sector ......................................... 5 Skills & Workforce Supply ................................................................................................... 12 Opportunities and Challenges ............................................................................................. 17 Consultee Feedback ........................................................................................................... 21 The Ports and Logistics Sector Skills Plan .......................................................................... 29 Priorities for Action .............................................................................................................. 29 Ports and Logistics Sector Skills Plan Delivery .................................................................... 31 Proposed Skills Interventions .............................................................................................