Mars Exploration Entry, Descent and Landing Challenges1,2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Support for the Development of These Album Pages Provided by Mystic Stamp Company America's Leading Stamp Dealer

SPACE ON STAMPS Created for free use in the public domain American Philatelic Society ©2010 • www.stamps.org Financial support for the development of these album pages provided by Mystic Stamp Company America’s Leading Stamp Dealer and proud of its support of the American Philatelic Society www.MysticStamp.com, 800-433-7811 Space on Stamps ou might say, it all started with the dream of flight and a desire to see the world as the birds do. For tens of thousands of years mankind has watched the stars Yand wondered what they might represent. Possibly the oldest constellation identified by humans as a permanent fixture in the night sky is Ursa Major, the Great Bear, the third largest of the constellations, and best known for the seven stars that make up its rump and tail: the Big Dipper (also known as the Plough or the Wagon). The most helpful of the sky maps, a line drawn though the two outside stars on the bowl of the “dipper” points directly to the North Star. Nothing successfully got human beings above the earth on a repeatable basis, however, until the age of ballooning. The first human to go aloft was a scientist, Pilatre de Rozier, who rose 250 feet into the sky in a hot air balloon and remained suspended above the French countryside for fifteen minutes in October 1783. A month later he and the Marquis d’Arlandes traveled about 5½ miles in the first free flight, using a balloon designed by the Montgolfier brothers. The first North American flight was made January 9, 1793, from Philadelphia to Gloucester County, New Jersey. -

Selection of the Insight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N

Manuscript Click here to download Manuscript InSight Landing Site Paper v9 Rev.docx Click here to view linked References Selection of the InSight Landing Site M. Golombek1, D. Kipp1, N. Warner1,2, I. J. Daubar1, R. Fergason3, R. Kirk3, R. Beyer4, A. Huertas1, S. Piqueux1, N. E. Putzig5, B. A. Campbell6, G. A. Morgan6, C. Charalambous7, W. T. Pike7, K. Gwinner8, F. Calef1, D. Kass1, M. Mischna1, J. Ashley1, C. Bloom1,9, N. Wigton1,10, T. Hare3, C. Schwartz1, H. Gengl1, L. Redmond1,11, M. Trautman1,12, J. Sweeney2, C. Grima11, I. B. Smith5, E. Sklyanskiy1, M. Lisano1, J. Benardino1, S. Smrekar1, P. Lognonné13, W. B. Banerdt1 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109 2State University of New York at Geneseo, Department of Geological Sciences, 1 College Circle, Geneseo, NY 14454 3Astrogeology Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001 4Sagan Center at the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035 5Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302; Now at Planetary Science Institute, Lakewood, CO 80401 6Smithsonian Institution, NASM CEPS, 6th at Independence SW, Washington, DC, 20560 7Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Imperial College, South Kensington Campus, London 8German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, 12489 Berlin, Germany 9Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA; Now at Central Washington University, Ellensburg, WA 98926 10Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 37996 11Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, Austin, TX 78712 12MS GIS Program, University of Redlands, 1200 E. Colton Ave., Redlands, CA 92373-0999 13Institut Physique du Globe de Paris, Paris Cité, Université Paris Sorbonne, France Diderot Submitted to Space Science Reviews, Special InSight Issue v. -

Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured By

Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured by MAVEN By Ali Rahmati Submitted to the graduate degree program in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Professor Thomas E. Cravens, Chair ________________________________ Professor Philip S. Baringer ________________________________ Professor David Braaten ________________________________ Professor Mikhail V. Medvedev ________________________________ Professor Stephen J. Sanders Date Defended: 22 January 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Ali Rahmati certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Oxygen Exosphere of Mars: Evidence from Pickup Ions Measured by MAVEN ________________________________ Professor Thomas E. Cravens, Chair Date approved: 22 January 2016 ii Abstract Mars possesses a hot oxygen exosphere that extends out to several Martian radii. The main source for populating this extended exosphere is the dissociative recombination of molecular oxygen ions with electrons in the Mars ionosphere. The dissociative recombination reaction creates two hot oxygen atoms that can gain energies above the escape energy at Mars and escape from the planet. Oxygen loss through this photochemical reaction is thought to be one of the main mechanisms of atmosphere escape at Mars, leading to the disappearance of water on the surface. In this work the hot oxygen exosphere of Mars is modeled using a two-stream/Liouville approach as well as a Monte-Carlo simulation. The modeled exosphere is used in a pickup ion simulation to predict the flux of energetic oxygen pickup ions at Mars. The pickup ions are created via ionization of neutral exospheric oxygen atoms through photo-ionization, charge exchange with solar wind protons, and electron impact ionization. -

MARS an Overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera Science

MARS MARS INFORMATICS The International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration Open Access Journals Science An overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera science investigation Michael C. Malin1, Kenneth S. Edgett1, Bruce A. Cantor1, Michael A. Caplinger1, G. Edward Danielson2, Elsa H. Jensen1, Michael A. Ravine1, Jennifer L. Sandoval1, and Kimberley D. Supulver1 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA, 92191-0148, USA; 2Deceased, 10 December 2005 Citation: Mars 5, 1-60, 2010; doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0001 History: Submitted: August 5, 2009; Reviewed: October 18, 2009; Accepted: November 15, 2009; Published: January 6, 2010 Editor: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University Reviewers: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University; R. Aileen Yingst, University of Wisconsin Green Bay Open Access: Copyright 2010 Malin Space Science Systems. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: NASA selected the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) investigation in 1986 for the Mars Observer mission. The MOC consisted of three elements which shared a common package: a narrow angle camera designed to obtain images with a spatial resolution as high as 1.4 m per pixel from orbit, and two wide angle cameras (one with a red filter, the other blue) for daily global imaging to observe meteorological events, geodesy, and provide context for the narrow angle images. Following the loss of Mars Observer in August 1993, a second MOC was built from flight spare hardware and launched aboard Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in November 1996. -

Tianwen-1: China's Mars Mission

Tianwen-1: China's Mars Mission drishtiias.com/printpdf/tianwen-1-china-s-mars-mission Why In News China will launch its first Mars Mission - Tianwen-1- in July, 2020. China's previous ‘Yinghuo-1’ Mars mission, which was supported by a Russian spacecraft, had failed after it did not leave the earth's orbit and disintegrated over the Pacific Ocean in 2012. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is also going to launch its own Mars mission in July, the Perseverance which aims to collect Martian samples. Key Points The Tianwen-1 Mission: It will lift off on a Long March 5 rocket, from the Wenchang launch centre. It will carry 13 payloads (seven orbiters and six rovers) that will explore the planet. It is an all-in-one orbiter, lander and rover system. Orbiter: It is a spacecraft designed to orbit a celestial body (astronomical body) without landing on its surface. Lander: It is a strong, lightweight spacecraft structure, consisting of a base and three sides "petals" in the shape of a tetrahedron (pyramid- shaped). It is a protective "shell" that houses the rover and protects it, along with the airbags, from the forces of impact. Rover: It is a planetary surface exploration device designed to move across the solid surface on a planet or other planetary mass celestial bodies. 1/3 Objectives: The mission will be the first to place a ground-penetrating radar on the Martian surface, which will be able to study local geology, as well as rock, ice, and dirt distribution. It will search the martian surface for water, investigate soil characteristics, and study the atmosphere. -

The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team

NASA Special Publication 6107 Human Exploration of Mars: The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team Stephen J. Hoffman, Editor David I. Kaplan, Editor Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas July 1997 NASA Special Publication 6107 Human Exploration of Mars: The Reference Mission of the NASA Mars Exploration Study Team Stephen J. Hoffman, Editor Science Applications International Corporation Houston, Texas David I. Kaplan, Editor Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas July 1997 This publication is available from the NASA Center for AeroSpace Information, 800 Elkridge Landing Road, Linthicum Heights, MD 21090-2934 (301) 621-0390. Foreword Mars has long beckoned to humankind interest in this fellow traveler of the solar from its travels high in the night sky. The system, adding impetus for exploration. ancients assumed this rust-red wanderer was Over the past several years studies the god of war and christened it with the have been conducted on various approaches name we still use today. to exploring Earth’s sister planet Mars. Much Early explorers armed with newly has been learned, and each study brings us invented telescopes discovered that this closer to realizing the goal of sending humans planet exhibited seasonal changes in color, to conduct science on the Red Planet and was subjected to dust storms that encircled explore its mysteries. The approach described the globe, and may have even had channels in this publication represents a culmination of that crisscrossed its surface. these efforts but should not be considered the final solution. It is our intent that this Recent explorers, using robotic document serve as a reference from which we surrogates to extend their reach, have can continuously compare and contrast other discovered that Mars is even more complex new innovative approaches to achieve our and fascinating—a planet peppered with long-term goal. -

Gulick, V CV2008.PDF

Curriculum Vitae: Dr. Virginia C. Gulick Nr\SA Amcs RcsearchCenter, lVfail Stop 239-20,Moffetl Field, Califoniia94035 (650) 604-0781 (office), Vireinia.C.GuUckr7lnase-gav IIDUCATION PhD (Geosciences);University of Arizona Ph.D. Thesis: Magnmtic Intrusiorts ancl l{ydrotlrcrmal Systents:Implicatiotts for the Fornmtion of Small Msrtian Valleys MS. (Geosciencr:s),Minor in Hydrology,The University of Arizona,Tucson Master Thesis: Origin ad Ev'olutionoJ'I'alle1's on the Martian Volcanoes:T'he Hatvaiittn.4nalog. B.A. (Geoscicnces),Rutgers University (Rutgers College) New Brunswick, New Jersey Senior Thesis:TIte Coral SeaSedinettt Study. I'[t.ft]SENTPOStrTION 1996-prres.:ResearchScientist (SETI InstitutePrincipal Investigator)& Adjunct Professor,Astronomy Dept.,NM StateUniv. u Mars ScienceLab 2009landing site selcction steering group nrembcr. r MRO'05 IIiRISE instrumentsciencc ternr nrcnibcr(200)-2009): Lead on flrn,ial & hydrothernral processes, E/PO & r'r,eb technologies. I-IiRl:iE E/PO website (http://nrarsox,eb.nas.uasa. gov/I{iRISE) presentation Planctary l)ata in E,ducational ' Invited to AGU's Scssion Using Settings. Presentationtitle: "MRO's High Re.solutionImaging ScienceExperirncnt ([iiRISE): EdLrcation And PubiicOutr each Plans",. r Invitedpanelist fot NASA's Leamingfiom the Frontier:Getting Planetary l)ata into the Herndsof EducatorsWorkshop at LPi, March 14,2004. ' Co-convcuerof thc Volcano/iceInteraction on Earthand Mars Conf-.,P.eykjavik, Iceland, August 2000. " Projectscicnce lead on Marsorveb:the Mars l,anding Site Studies& Global Visualizationweb cnvironmentr:ffort (hItpJ4UDSIylb.nas.liUagq1llandinqsites).1998-present. o ScienceCoI for the Clickworkersl'roject; NASA's Experimeutin distributeddata analysis by the p ubl i c w eb si tc (liltd&lekfi g*9t$.3l9.qag4.gev ) 20 0 0-p resent. -

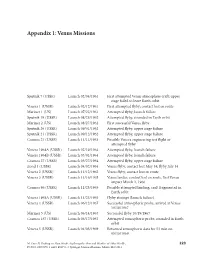

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Deep Space 2: the Mars Microprobe Project and Beyond

First International Conference on Mars Polar Science 3039.pdf DEEP SPACE 2: THE MARS MICROPROBE PROJECT AND BEYOND. S. E. Smrekar and S. A. Gavit, Mail Stop 183-501, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasa- dena CA 91109, USA ([email protected]). Mission Overview: The Mars Microprobe Proj- System Design, Technologies, and Instruments: ect, or Deep Space 2 (DS2), is the second of the New Telecommunications. The DS2 telecom system, Millennium Program planetary missions and is de- which is mounted on the aftbody electronics plate, signed to enable future space science network mis- relays data back to earth via the Mars Global Surveyor sions through flight validation of new technologies. A spacecraft which passes overhead approximately once secondary goal is the collection of meaningful science every 2 hours. The receiver and transmitter operate in data. Two micropenetrators will be deployed to carry the Ultraviolet Frequency Range (UHF) and data is out surface and subsurface science. returned at a rate of 7 Kbits/second. The penetrators are being carried as a piggyback Ultra-low-temperature lithium primary battery. payload on the Mars Polar Lander cruise ring and will One challenging aspect of the microprobe design is be launched in January of 1999. The Microprobe has the thermal environment. The batteries are likely to no active control, attitude determination, or propulsive stay no warmer than -78° C. A lithium-thionyl pri- systems. It is a single stage from separation until mary battery was developed to survive the extreme landing and will passively orient itself due to its aero- temperature, with a 6 to 14 V range and a 3-year shelf dynamic design (Fig. -

Aerothermodynamic Design of the Mars Science Laboratory Heatshield

Aerothermodynamic Design of the Mars Science Laboratory Heatshield Karl T. Edquist∗ and Artem A. Dyakonovy NASA Langley Research Center, Hampton, Virginia, 23681 Michael J. Wrightz and Chun Y. Tangx NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California, 94035 Aerothermodynamic design environments are presented for the Mars Science Labora- tory entry capsule heatshield. The design conditions are based on Navier-Stokes flowfield simulations on shallow (maximum total heat load) and steep (maximum heat flux, shear stress, and pressure) entry trajectories from a 2009 launch. Boundary layer transition is expected prior to peak heat flux, a first for Mars entry, and the heatshield environments were defined for a fully-turbulent heat pulse. The effects of distributed surface roughness on turbulent heat flux and shear stress peaks are included using empirical correlations. Additional biases and uncertainties are based on computational model comparisons with experimental data and sensitivity studies. The peak design conditions are 197 W=cm2 for heat flux, 471 P a for shear stress, 0.371 Earth atm for pressure, and 5477 J=cm2 for total heat load. Time-varying conditions at fixed heatshield locations were generated for thermal protection system analysis and flight instrumentation development. Finally, the aerother- modynamic effects of delaying launch until 2011 are previewed. Nomenclature 1 2 2 A reference area, 4 πD (m ) CD drag coefficient, D=q1A D aeroshell diameter (m) 2 Dim multi-component diffusion coefficient (m =s) ci species mass fraction H total enthalpy -

Aerocapture FS-Pdf.Indd

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Marshall Space Flight Center Huntsville, Alabama 35812 FS-2004-09-127-MSFC July 2004 Aerocapture Technology NASA technologists are working to develop ways to place robotic space vehicles into long-duration, scientific orbits around distant Solar System destinations without the need for the heavy, on-board fuel loads that have historically inhibited vehicle performance, mission dura- tion and available mass for science payloads. Aerocapture -- a flight maneuver that inserts a space- craft into its proper orbit once it arrives at a planet -- is part of a unique family of “aeroassist” technologies under consideration to achieve these goals and enable robust science missions to any planetary body with an appreciable atmosphere. Aerocapture technology is just one of many propulsion technologies being developed by NASA technologists and their partners in industry and academia, led by NASA’s In-Space Propulsion Technology Office at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. The Center implements the In-Space Propulsion Technolo- gies Program on behalf of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Aerocapture uses a planet’s or moon’s atmosphere to accomplish a quick, near-propellantless orbit capture to place a space vehicle in its proper orbit. The atmo- sphere is used as a brake to slow down a spacecraft, transferring the energy associated with the vehicle’s high speed into thermal energy. Aerocapture entering Mars Orbit. The aerocapture maneuver starts with an approach trajectory into the atmosphere of the target body. The dense atmosphere creates friction, slowing the craft and placing it into an elliptical orbit -- an oval shaped orbit. -

Overview of the ASPIRE Project June 12-16, 2017 - the Hague, NL

14th International Planetary Probes Workshop Overview of the ASPIRE Project June 12-16, 2017 - The Hague, NL. Clara O’Farrell, Ian Clark & Mark Adler Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology © 2017 California Institute of Technology. Government Sponsorship Acknowledged. ASPIRE Disk-Gap-Band (DGB) Parachute Heritage MSL (2012) MER (2004) • Developed in the 60s & 70s Viking (1974) for Viking – High Altitude Testing – Wind Tunnel Testing – Low Altitude Drop • Successfully used on 5 Mars missions – Leveraged Viking development Viking BLDT Test MER Drop Test MSL Wind Tunnel Test Image credit: mars.nasa.gov June 12-16, 2017 14th International Planetary Probes Workshop 2 jpl.nasa.gov Aerospace in recent DGB designs: Clark & Tanner, IEEE Broadcloth stress Conference Paper 2466 (2017): (per unit length) Broadcloth ultimate load estimated by treating the disk as a pressure vessel: Disk diameter have been eroding jpl.nasa.gov 3 180 Actual Flight Load ASPIRE 160 Parachute Design Load Broadcloth Ultimate Load DGB Heritage & Design Margins Strength margins may 140 f b l 120 • 3 0 1 x , 100 d a o L e 80 t u h c a r 60 a P 40 parachutes well below those achieved in supersonic tests 20 stresses seen in subsonic testing may not bound the 14th International Planetary Probes Workshop -Densityringsail Supersonic0 Decelerators Project saw failures of two 9. 19 12 12 12 S V V V V P S O P M 1 . P ik ik ik ik at pi p ho S m 7 2 2 2 E i i i i h r p e L m m m m D n n n n f it o n M - g g g g in rt i 1 M M M M II A A I I d u x .