Film and Accountability: Ritwik Ghatak's „Image Discourse' on Bengal's Partition Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Indian Films on Partition of India

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Manoj Sharma, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 3, pp. 492 - 501 Date of Publication: 15th December, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.33.492501 This paper can be cited as: Sharma, M. (2017). Cinematic Representations of Partition of India. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 492-501. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF PARTITION OF INDIA Dr. Manoj Sharma Assistant Professor, Modern Indian History, Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 – India [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The partition of India in August 1947 marks a watershed in the modern Indian history. The creation of two nations, India and Pakistan, was not only a geographical division but also widened the chasm in the hearts of the people. The objective of the paper is to study the cinematic representations of the experiences associated with the partition of India. The cinematic portrayal of fear generated by the partition violence and the terror accompanying it will also be examined. Films dealing with partition have common themes of displacement of thousands of masses from their homelands, being called refugees in their own homeland and their struggle for survival in refugee colonies. They showcase the trauma of fear, violence, personal pain, loss and uprooting from native place. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 4.727 (SJIF) Draupadi’s Resistance in Saoli Mitra’s Nathabati Anathabat Suryakant Yadav Research Scholar Department of English and Modern European Languages University of Lucknow, Lucknow Abstract: This paper deals with the character of Draupadi depicted in the modern retellings of The Mahabharata. Draupadi, like the great Indian epics, is a pan-Indian phenomenon that has been portrayed in a number of Indian texts, be it poem, prose or drama. There have been many women who have come out as powerful characters in Hindu mythology and women writers such as Saoli Mitra bring out the discourse of such personalities. The status of woman in myth making is very significant, and Draupadi stands as the embodiment of woman empowerment as she elevates herself above the male dominated social order. Saoli Mitra represents Draupadi as the image of retaliation and exemplifies her agonies, her subjugation and ultimately her liberation from the clutches of patriarchy. Keywords: myth; retaliation; upliftment; stereotypes; power; protest. The Mahabharata is a veritable treasure house of Indian philosophy, religion and culture and has rightly been considered the „fifth veda‟. A graphic tale of men and women, some with divine attributes, dwelling on all convincible situations in life, this epic is a whole literature in itself, ageless and everlasting. Irawati Karve writes that the scope of The Mahabharata “is wide ranging in time, in space and in its cast of characters. Heroes and cowards, villains and good men, impulsive fools and wise men, ugly men and fair ones are all depicted in the course of its narrative. -

Do Not Forget Me

Nandita Raman DO NOT FORGET ME sepiaEYE is honored to present our first solo exhibition of Nandita Raman entitled FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE DO NOT FORGET ME which features works from series, Film Studio (2014) and Cinema Play House (2006-2009). EXHIBITION LOCATION DO NOT FORGET ME borrows its title from a short story by Alexander Kluge (Cinema 547 West 27th Street, #608 Stories, 2007) about a German actor’s desire to be loved and remembered forever. New York, NY 10001 The muted color works in Film Studio touch on the objects that produced lasting memories: cameras draped in faded fabrics, well-worn ladders— shrouded remnants EXHIBITION DATES of a once teeming industry left in the dust. Raman’s photographs of these objects, September 28 – November 17, 2018 tools, and spaces that at one time rendered the imaginary visible, serve as mnemonic RECEPTION devices that spark anecdotes and recollections of the history of Indian cinema. Thursday, September 27, 6-8pm In Manik-da’s Camera, there appears to be three floating cameras enveloped in a haze achieved by using the image multiplier filter from the floating camera’s kit. PRESS CONTACT These filters were once popular for depicting fantastical dream sequences in [email protected] Indian films. Satyajit Ray, the famous filmmaker, was known amongst his friends and the industry as Manik-da. The camera he shot on was forever known as that camera. As with past photographic series, Raman applies her almost decade-long exploration of temporality, impermanence, and the unreliability of memory to Indian cinematic history. “When I went back to Kolkata in 2013 a few years after photographing the cinema halls there, it was evident to trace the footsteps of film backwards from the cinema hall to film studio. -

Unit-2 Silent Era to Talkies, Cinema in Later Decades

Bachelor of Arts (Honors) in Journalism& Mass Communication (BJMC) BJMC-6 HISTORY OF THE MEDIA Block - 4 VISUAL MEDIA UNIT-1 EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA UNIT-2 SILENT ERA TO TALKIES, CINEMA IN LATER DECADES UNIT-3 COMING OF TELEVISION AND STATE’S DEVELOPMENT AGENDA UNIT-4 ARRIVAL OF TRANSNATIONAL TELEVISION; FORMATION OF PRASAR BHARATI The Course follows the UGC prescribed syllabus for BA(Honors) Journalism under Choice Based Credit System (CBCS). Course Writer Course Editor Dr. Narsingh Majhi Dr. Sudarshan Yadav Assistant Professor Assistant Professor Journalism and Mass Communication Dept. of Mass Communication, Sri Sri University, Cuttack Central University of Jharkhand Material Production Dr. Manas Ranjan Pujari Registrar Odisha State Open University, Sambalpur (CC) OSOU, JUNE 2020. VISUAL MEDIA is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licences/by-sa/4.0 Printedby: UNIT-1EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY, LITHOGRAPHY AND CINEMA Unit Structure 1.1. Learning Objective 1.2. Introduction 1.3. Evolution of Photography 1.4. History of Lithography 1.5. Evolution of Cinema 1.6. Check Your Progress 1.1.LEARNING OBJECTIVE After completing this unit, learners should be able to understand: the technological development of photography; the history and development of printing; and the development of the motion picture industry and technology. 1.2.INTRODUCTION Learners as you are aware that we are going to discuss the technological development of photography, lithography and motion picture. In the present times, the human society is very hard to think if the invention of photography hasn‘t been materialized. It is hard to imagine the world without photography. -

Music, Partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah

Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 120 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Maulana Azad College, University of Calcutta, [email protected] At a time when the ‘commercial’ Bengali film directors were busy caricaturing the language and the mannerisms of the East-Bengal refugees, specifically in Calcutta, using them as nothing but mere butts of ridicule, Ritwik Ghatak’s films portrayed these ‘refugees’, who formed the lower middle class of the society, as essentially torn between a nostalgia for an utopian motherland and the traumatic present of the post-partition world of an apocalyptic stupor. Ghatak himself was a victim of the Partition of India in 1947. He had to leave his homeland for a life in Calcutta where for the rest of his life he could not rip off the label of being a ‘refugee’, which the natives of the ‘West’ Bengal had labelled upon the homeless East Bengal masses. The melancholic longing for the estranged homeland forms the basis of most of Ghatak’s films, especially the trilogy: Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komol Gondhar (1960) and Subarnarekha (1961). Ghatak’s running obsession with the post-partition trauma acts as one of the predominant themes in the plots of his films. To bring out the tragedy of the situation more vividly, he deploys music and melodrama as essential tropes. Ghatak brilliantly juxtaposes different genres of music, from Indian Classical Music and Rabindra Sangeet to folk songs, to carve out the trauma of a soul striving for recognition in a new land while, at the same time, trying hard to cope with the loss of its ‘motherland’. -

A Complete Profile of Rangroop

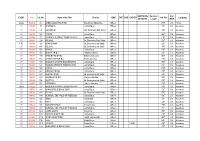

MMMAJOR PRODUCTIONS OF RANGRANG----ROOPROOP SINCE THE INCEPTION: Total Name Of The Year No. Of Drama By Directed By Production Shows 1969-70 Michhil 12 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1972-73 Akay Akay Sunya 9 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1979-80 Kanthaswar 151 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Sanskrit play: Banabhatta; Adaptation : 1982-83 Kadambari 50 Goutam Mukherjee Dr. K.K. Chakraborty Story: Subodh Ghosh 1984-85 Andhkarer Rang 62 Script: Sima Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry Do. Prahasan 62 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry 1987-88 Clown 110 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee 1988-89 Bikalpa 74 Sima Mukhopadhyay Goutam Mukherjee Dwijen Banerjee & 1991-92 Bhanga Boned 130 Sima Mukhopadhyay Saonli Mitra 1992-93 Tringsha Shatabdi 5 Badal Sarkar Kaliprosad Ghosh 1993-94 Boli 11 Tripti Mitra Sima Mukhopadhyay 1994-95 Je Jan Achhey 187 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Majhkhane Sima Mukhopadhyay 1996-97 24 Abanindranath Tagore Aalor Phulki & K K Mukhopadhyay Panu Santi Sima Mukhopadhyay Krishna Kishore 1998-99 53 Cheyechhilo (Story: Ramanath Roy) Mukhopadhyay 1999- Aaborto 27 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2000 2000-01 Sunyapat 34 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Drama: Olwen Wymark 2002-03 Khnuje Nao 37 Adaptation: Swatilekha Sengupta Rudraprasad Sengupta Je Jan Achhey 2003-04 Majhkhane 32 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay (Revive) 2004-05 Sesh Raksha 38 Rabindranath Tagore Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2005-06 He Mor Debota 10 (Story: Deborshee Sima Mukhopadhyay Saroghee) -

Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry: Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA Aparajita Sengupta University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sengupta, Aparajita, "NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA" (2011). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 129. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aparajita Sengupta The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aparajita Sengupta Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Michel Trask, Professor of English Lexington, Kentucky 2011 Copyright© Aparajita Sengupta 2011 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA In spite of the substantial amount of critical work that has been produced on Indian cinema in the last decade, misconceptions about Indian cinema still abound. Indian cinema is a subject about which conceptions are still muddy, even within prominent academic circles. The majority of the recent critical work on the subject endeavors to correct misconceptions, analyze cinematic norms and lay down the theoretical foundations for Indian cinema. -

Annual Report 2011-2012

Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2011-2012 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) Shri B.N. Srikrishna (w. e. f. 1st January, 2012) Mr. Suresh Kumar Neotia Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. Rajiv Mehrishi Dr. (Mrs.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. Kisan Mehta Mr. Najeeb Jung Dr. (Ms.) Sukrita Paul Kumar Dr. U.D. Choubey Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Lt. Gen. V.R. Raghavan Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) Mr. B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Lt. Gen. (Retd.) V.R. Raghavan Mr. Jnan Prakash, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. B. Chakravorty Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms. Premola Ghose, Chief Programme Division Mr. Vijay Kumar Thukral, Executive Chef Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief Maintenance Division Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager (Catering) Ms. Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Ms. Madhu Gupta, Dy. General Manager (Hostel/House Keeping) Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms. Seema Kohli, Membership Officer (w. e. f. August 2011) Annual Report 2011-2012 As always, it is a privilege to present the 51th Annual Report of the India International Centre for the year commencing 1 February 2011 and ending 31 January 2012. -

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col. -

Of Roots and Rootlessness: Music, Partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The South Asianist Journal Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 | ISSN 2050-487X | www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk www.southasianist.ed.ac.uk | ISSN 2050-487X | pg. 120 Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 120–136 Of roots and rootlessness: music, partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah Maulana Azad College, University of Calcutta, [email protected] At a time when the ‘commercial’ Bengali film directors were busy caricaturing the language and the mannerisms of the East-Bengal refugees, specifically in Calcutta, using them as nothing but mere butts of ridicule, Ritwik Ghatak’s films portrayed these ‘refugees’, who formed the lower middle class of the society, as essentially torn between a nostalgia for an utopian motherland and the traumatic present of the post-partition world of an apocalyptic stupor. Ghatak himself was a victim of the Partition of India in 1947. He had to leave his homeland for a life in Calcutta where for the rest of his life he could not rip off the label of being a ‘refugee’, which the natives of the ‘West’ Bengal had labelled upon the homeless East Bengal masses. The melancholic longing for the estranged homeland forms the basis of most of Ghatak’s films, especially the trilogy: Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), Komol Gondhar (1960) and Subarnarekha (1961). Ghatak’s running obsession with the post-partition trauma acts as one of the predominant themes in the plots of his films.