Indian Films on Partition of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Media Journal–Pakistan Edition Vol.Xii, Issue-01, Spring, 2019 1

GLOBAL MEDIA JOURNAL–PAKISTAN EDITION VOL.XII, ISSUE-01, SPRING, 2019 Screen Adaptation: An Art in Search of Recognition Sharaf Rehman1 Abstract This paper has four goals. It offers a brief history and role of the process of screen adaptation in the film industries in the U.S. and the Indian Subcontinent; it explores some of the theories that draw parallels between literary and cinematic conventions attempting to bridge literature and cinema. Finally, this paper discusses some of the choices and strategies available to a writer when converting novels, short stories, and stage play into film scripts. Keywords: Screen Adoption, Subcontinent Film, Screenplay Writing, Film Production in Subcontinent, Asian Cinema 1 Professor of Communication, the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, USA 1 GLOBAL MEDIA JOURNAL–PAKISTAN EDITION VOL.XII, ISSUE-01, SPRING, 2019 Introduction Tens of thousands of films (worldwide) have their roots in literature, e.g., short stories and novels. One often hears questions like: Can a film be considered literature? Is cinema an art form comparable to paintings of some of the masters, or some of the classics of literature? Is there a relationship or connection between literature and film? Why is there so much curiosity and concern about cinema? Arguably, no other storytelling medium has appealed to humanity as films. Silent films spoke to audiences beyond geographic, political, linguistic, and cultural borders. Consequently, the film became the first global mass medium (Hanson, 2017). In the last one hundred years, audiences around the world have shown a boundless appetite for cinema. People go to the movies for different social reasons, and with different expectations. -

Yash Chopra the Legend

YASH CHOPRA THE LEGEND Visionary. Director. Producer. Legendary Dream Merchant of Indian Cinema. And a trailblazer who paved the way for the Indian entertainment industry. 1932 - 2012 Genre defining director, star-maker and a studio mogul, Yash Chopra has been instrumental in shaping the symbolism of mainstream Hindi cinema across the globe. Popularly known as the ‘King of Romance’ for his string of hit romantic films spanning over a five-decade career, he redefined drama and romance onscreen. Born on 27 September 1932, Yash Chopra's journey began from the lush green fields of Punjab, which kept reappearing in his films in all their splendour. © Yash Raj Films Pvt. Ltd. 1 www.yashrajfilms.com Yash Chopra started out as an assistant to his brother, B. R. Chopra, and went on to direct 5 very successful films for his brother’s banner - B. R. Films, each of which proved to be a significant milestone in his development as a world class director of blockbusters. These were DHOOL KA PHOOL (1959), DHARMPUTRA (1961), WAQT (1965) - India’s first true multi-starrer generational family drama, ITTEFAQ (1969) & AADMI AUR INSAAN (1969). He has wielded the baton additionally for 4 films made by other film companies - JOSHILA (1973), DEEWAAR (1975), TRISHUL (1978) & PARAMPARA (1993). But his greatest repertoire of work were the 50 plus films made under the banner that he launched - the banner that stands for the best of Hindi cinema - YRF. Out of these films, he directed 13 himself and these films have defined much of the language of Hindi films as we know them today. -

War on Terror Partnership and Growing/Mounting/Increasing

Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 5, No. 1, January – June, 2019, pp. 119 – 130 Pakistan in the Bollywood Movies: A Discourse Analysis Nauman Sial International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. Yasar Arafat International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. Abid Zafar International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. ABSTRACT Pakistan and India had been the rival nations after the partition of Sub-continent in 1947. Both countries have fought many wars against each other including the 1948 Kashmir war, 1965 war, 1971 war and the Kargil war in 1999. But yet the relations remain on the conflicting peak. Indian government has always used the Hindi language cinema i.e. Bollywood as their main weapon. This research is being carried out to analyze the image of Pakistan that is being presented in the Bollywood Movies after the attacks on the Indian city Mumbai on November 26, 2008. Also, how the image of Pakistanis, the military forces/intelligence agencies and the religious groups of Pakistan are being shown in the Bollywood movies. Three films have been selected in this research which portrayed the image of Pakistan. Discourse analysis has been used as a research design for this study. The dialogues of all the movies have been analysed and interpreted which show that movies have portrayed a negative image of Pakistan, its people and also its military/intelligence agencies and religious groups. The five filters of propaganda model by Herman and Chomsky have also been observed and proved in this research work. Key Words: Film, Propaganda, Bollywood, A Propaganda Model, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), Research and Analysis Wing (RAW) Introduction Film or movie is an art that has borrowed itself from the other arts i.e. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial Board

June 2021 Volume 27, Number 6S AACE Annual Meeting 2021 Abstracts Editorial board Editor-in-Chief Pauline M. Camacho, MD, FACE Suleiman Mustafa-Kutana, BSC, MB, CHB, MSC Maywood, Illinois, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, FACE Atlanta, Georgia, United States Andrea Coviello, MD, MSE, MMCi Karel Pacak, MD, PhD, DSc Durham, North Carolina, United States Bethesda, Maryland, United States Associate Editors Natalie E. Cusano, MD, MS Amanda Powell, MD Maria Papaleontiou, MD New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Tobias Else, MD Gregory Randolph, MD Melissa Putman, MD Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Vahab Fatourechi, MD Daniel J. Rubin, MD, MSc Harold Rosen, MD Rochester, Minnesota, United States Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Ruth Freeman, MD Joshua D. Safer, MD Nicholas Tritos, MD, DS, FACP, FACE New York, New York, United States New York, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Rajesh K. Garg, MD Pankaj Shah, MD Boston, Massachusetts, United States Staff Rochester, Minnesota, United States Eliza B. Geer, MD Joseph L. Shaker, MD Paul A. Markowski New York, New York, United States Milwaukee, Wisconsin, United States CEO Roma Gianchandani, MD Lance Sloan, MD, MS Elizabeth Lepkowski Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States Lufkin, Texas, United States Chief Learning Officer Martin M. Grajower, MD, FACP, FACE Takara L. Stanley, MD Lori Clawges The Bronx, New York, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Senior Managing Editor Allen S. Ho, MD Devin Steenkamp, MD Corrie Williams Los Angeles, California, United States Boston, Massachusetts, United States Peer Review Manager Michael F. -

The Partition of India and Pakistan in the Novels of Selected Writers in South Asian Countries

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture (Linqua- IJLLC) August 2014 edition Vol.1 No.1 THE PARTITION OF INDIA AND PAKISTAN IN THE NOVELS OF SELECTED WRITERS IN SOUTH ASIAN COUNTRIES G.Sankar Assistant Professor Department of English Vel Tech Dr.RR& Dr.SR Technical University Chennai-600062 India Abstract The partition of India and the associated bloody riots inspired many creative minds in India and Pakistan to create literary/cinematic depictions of this event.[1] While some creations depicted the massacres during the refugee migration, others concentrated on the aftermath of the partition in terms of difficulties faced by the refugees in both side of the border. Even now, more than 60 years after the partition, works of fiction and films are made that relate to the events of partition.Literature describing the human cost of independence and partition comprises Khushwant Singh's Train to Pakistan (1956), several short stories such as Toba Tek Singh (1955) by Saadat Hassan Manto, Urdu poems such as Subh-e-Azadi (Freedom’s Dawn, 1947) by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Bhisham Sahni's Tamas (1974), Manohar Malgonkar's A Bend in the Ganges (1965), and Bapsi Sidhwa's Ice-Candy Man (1988), among others.[2][3] Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children (1980), which won the Booker Prize and the Booker of Bookers, weaved its narrative based on the children born with magical abilities on midnight of 14 August 1947.[3] Freedom at Midnight (1975) is a non-fiction work by Larry Collinsand Dominique Lapierre that chronicled the events surrounding the first Independence Day celebrations in 1947. -

Iffco Lecture Book

26th tokgjyky usg: Lekjd bQdks O;k[;ku Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial IFFCO Lecture Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial IFFCO Lecture is being organized by IFFCO every year to promulgate the cooperative principles and ideology advocated by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Architect of Modern India. The Cooperative Award Ceremony is a source of encouragement and inspiration to Cooperative leaders which recognizes their efforts and spirit for the overall growth of the society. oDrk@ Speaker MkW- fxjh'k dukZM] lqizfl) ys[kd] fo[;kr fQYe o ukVddkj Dr. Girish Karnad, Eminent Author, Noted Cinema and Theater Personality 15 uoEcj] 2013 ¼'kqØokj½ vijkºu & 3-00 cts Friday, 15th November 2013, at 3.00 P.M. bafM;u QkjelZ QfVZykbtj dksvkijsfVo fyfeVsM INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISER COOPERATIVE LIMITED ok¡ 26 th tokgj yky usg: Lekjd bQdks O;k[kku Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial IFFCO Lecture Hkkjrh; flusek vkSj jk"Vª&fuekZ.k Indian Cinema and the Creation of Nation oDrk@ Speaker MkW- fxjh'k dukZM lqizfl) ys[kd] fo[;kr fQYe o ukVddkj Dr. Girish Karnad Eminent Author, Noted Cinema and Theater Personality 15 uoEcj] 2013 15 November, 2013 ok¡ 26 th tokgj yky usg: Lekjd bQdks O;k[kku Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial IFFCO Lecture Hkkjrh; flusek vkSj jk"Vª&fuekZ.k Indian Cinema and the Creation of Nation oDrk@ Speaker MkW- fxjh'k dukZM lqizfl) ys[kd] fo[;kr fQYe o ukVddkj Dr. Girish Karnad Eminent Author, Noted Cinema and Theater Personality 15 uoEcj] 2013 15 November, 2013 INDIAN CINEMA AND THE Hkkjrh; flusek vkSj jk"Vª&fuekZ.k CREATION OF A NATION & fxjh'k dukZM - GIRISH KARNAD loZizFke eSa ;g dguk pkgw¡xk fd bafM;u QkjelZ Let me say right at the start what an honour it is QÆVykbtj dksvkijsfVo fyfeVsM ¼bQdks½ dh vksj ls to be standing here to deliver the Jawaharlal Nehru tokgjyky usg: Lekjd O;k[;ku nsus gsrq vkids chp Memorial Lecture for the Indian Farmers Fertiliser mifLFkr gksuk esjs fy, lEeku dh ckr gSA eSa vius vkidks Cooperative. -

Open Letter Against Sec 377 by Amartya Sen, Vikram Seth and Others, 2006

Open Letters Against Sec 377 These two open letters bring together the voices of many of the most eminent and respected Indians, collectively saying that on the grounds of fundamental human rights Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, a British-era law that criminalizes same-sex love between adults, should be struck down immediately. The eminent signatories to these letters are asking our government, our courts, and the people of this country to join their voices against this archaic and oppressive law, and to put India in line with other progressive countries that are striving to realize the foundational goal of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that “All persons are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” They have come together to defend the rights and freedom not just of sexual minorities in India but to uphold the dignity and vigour of Indian democracy itself. Navigating Through This Press Kit This kit contains, in order, i. A statement by Amartya Sen, Nobel Laureate ii. The text of the main Open Letter iii. The list of Signatories iv. Sexual minorities in India - Frequently Asked Questions and Clarifications v. A summary of laws concerning the rights and situation of sexual minorities globally vi. Contact Information for further information/interviews Strictly embargoed until 16th September 2006 Not for distribution or publication without prior permission of the main signatories. All legal rights reserved worldwide. 1 In Support Cambridge 20 August 2006 A Statement in Support of the Open Letter by Vikram Seth and Others I have read with much interest and agreement the open letter of Vikram Seth and others on the need to overturn section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. -

VIDURA 1 from the Editor Even As Social Media Takes Charge, Newspapers Retain Their Charm

A JOURNAL OF THE PRESS INSTITUTE OF INDIA ISSN 0042-5303 July-September 2016 Volume 8 Issue 3 Rs 50 Tobacco habit is a disease, must be stopped CONTENTS • For the sake of media with a conscience / Sakuntala Globally, with control of communicable disease, we see an Narasimhan increasing trend in non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In • A penchant for hype and India, however, control of communicable disease is only partial. sensationalism / Pratab We have therefore to bear the burden of existing communicable Ramchand diseases such as tuberculosis, malaria and HIV and also the • A media dialogue on increasing burden of NCDs, says Dr V. Shanta connectivity / Shastri Ramachandran he past few decades have been witness to phenomenal changes in the • Charm and chivalry in health scenario, from an era of high mortality and morbidity to an era of China / Asma Masood Tcontrol and curability of communicable diseases. There is no panic about • The promise and reality cholera, typhoid, hepatitis and polio, and many others are under control. India of Indian politics / has been declared 'polio free'. The advent of vaccine and antibiotics made this J.V. Vil'anilam possible. • Bengal's transgender poll The World Health Organisation in its statistics report has referred to officers make history / Epidemics of NCDs emerging or accelerating in most developing countries. Dipanjana Dasgupta NCDs constitute the leading cause of death and disabilities world over. The • Nothing private about disability adjusted life years (DALY) which was 1:0.5 in 1990 is expected to be domestic violence / Pushpa 1:2.3 by 2020. Achanta The increase in NCDs is a result of increase in life expectancy, control of • How a billion can help communicable disease and lifestyle changes. -

Film and Accountability: Ritwik Ghatak's „Image Discourse' on Bengal's Partition Dr

The International journal of analytical and experimental modal analysis ISSN NO: 0886-9367 Film and Accountability: Ritwik Ghatak's „Image Discourse' on Bengal's Partition Dr. Sravani Biswas Associate Professor, Department of English Tezpur University Napaam, Tezpur: 784028, Assam Email: [email protected] Mobile: +91 8638750574 Title: Film and Accountability: Ritwik Ghatak's „Image Discourse' on Bengal's Partition Abstract: The objective of the paper is to closely examine Ritwik Ghatak‟s film Subarnarekha, to analyse the partition-discourse that forms the centre of his directorial consciousness. The paper addresses Ghatak‟s narration in terms of film semiotics. Two more films of Ghatak have been cited for further illustration. It is observed that the river Subarnarekha (Golden Streak) is the leitmotif of moral degeneration undergone by the refugees. It is a unique and bold take on the historical tragedy which had naturally led to filmic depictions of the refugees as victims. Ghatak steps beyond the cliché in a soul searching venture to identify why this partition continues to inflict decadence. The dislocated refugees resist any paradigm shift. Romantic nostalgia turns them blind to all the ingrained social and moral weaknesses that had, in the past, led to the Partition. In order to keep alive the past, they carry the germs, which, in hostile conditions erupt to destroy. The camera goes on searching for the river Subarnarekha which, most of the time remains invisible. It comes back with all its life only when the story reaches that point of possible paradigm shift, which Ghatak had envisioned for the refugees. -

Fezana Journal

PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Fall/September 2010, PAIZ 1379 AY 3748 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, 3 Message from the President www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 9 Financial Report Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] 34 YLEP UPDATE Yezdi Godiwalla: [email protected] Behram Panthaki::[email protected] Behram Pastakia: [email protected] 37 Global Health Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla 97 In The News Subscription Managers: Kershaw Khumbatta : [email protected] 112 Interfaith /Interalia Arnavaz Sethna: [email protected] WINTER 2010 115 North American Mobeds’ Council SHAHNAMEH: THE SOUL OF IRAN GUEST EDITOR TEENAZ JAVAT 120 Personal Profiles SPRING 2011 124 Letters to the editor ZARATHUSHTI PHILANTHROPY GUEST EDITOR DR MEHROO M. PATEL 129 Milestones Photo on cover: 141 Between the Covers 147 Business Mehr- Avan – Adar 1379 AY (Fasli) Ardebehesht – Khordad – Tir 1380 AY (Shenshai) Khordad - Tir – Amordad 1380 AY (Kadimi) Cover design Opinions expressed in the FEZANA Journal do not necessarily reflect the views of Feroza Fitch of FEZANA or members of this publications’s editorial board Lexicongraphics Please note that past issues of The Journal are available to the public, both in print and online through our archive at fezana.org. -

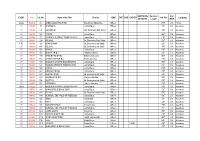

EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P

UMATIC/DG Duration/ Col./ EVENT Year Lib. No. Name of the Film Director 35MM DCP BRD DVD/CD Sub-Title Language BETA/DVC Lenght B&W Gujrat Festival 553 ANDHA DIGANTHA (P. B.) Man Mohan Mahapatra 06Reels HST Col. Oriya I. P. 1982-83 73 APAROOPA Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1985-86 201 AGNISNAAN DR. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1986-87 242 PAPORI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 252 HALODHIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 294 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia 06Reels EST Col. Assamese F.O.I. 1985-86 429 AGANISNAAN Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 09Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1988-89 440 KOLAHAL Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 06Reels SST Col. Assamese I. P. 1989-90 450 BANANI Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 483 ADAJYA (P. B.) Satwana Bardoloi 05Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 494 RAAG BIRAG (P. B.) Bidyut Chakravarty 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1996-97 500 HASTIR KANYA(P. B.) Prabin Hazarika 03Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 509 HALODHIA CHORYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1987-88 522 HALODIA CHORAYE BAODHAN KHAI Jahnu Barua 07Reels FST Col. Assamese I. P. 1990-91 574 BANANI Jahnu Barua 12Reels HST Col. Assamese I. P. 1991-92 660 FIRINGOTI (P. B.) Jahnu Barua 06Reels EST Col. Assamese I. P. 1992-93 692 SAROTHI (P. B.) Dr. Bhabendranath Saikia 05Reels EST Col.