Of Roots and Rootlessness: Music, Partition and Ghatak Priyanka Shah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

SPECIAL REPORT an Analysis of the June 1-15, 2008 the Fortnightly from Afaqs! Mobile Marketing Business in India 16

Rs 40 THE SPECIAL REPORT An analysis of the June 1-15, 2008 The fortnightly from afaqs! mobile marketing business in India 16 PROFILE Mohit Anand Making the transition from software to Channel [V]. 22 SPRITE Being Upfront How a consistent message worked like magic. 24 DEFINING MOMENTS Gullu Sen Anything can change your life, feels this adman. TV SHOWS The Power of Stars 12 WEBSITES Are details really everything? A report At Home 14 on whether execution in Indian PARLE MONACO advertising matches the idea. The Lighter Side 38 28 STAR COMIC BOOKS Animated in Print 38 The fortnightly from agencyfaqs! This fortnight... Volume III, Issue 21 he subject of this issue’s cover story has been provoked by the impending Cannes festival EDITOR T– but is not really about it. In the course of covering international awards, we have found Sreekant Khandekar that the quality of execution in Indian advertising keeps cropping up. The issue generally gets sidelined because the natural focus is the idea behind a campaign. PUBLISHER Prasanna Singh Craft and execution are not a pre-requisite for awards alone. It is the stuff of everyday advertising life, the very thing that can enhance the impact of an idea dramatically – EXECUTIVE EDITOR or wreck it, quite as easily. Happydent, Fevicol and Nike are three examples of the M Venkatesh delightful consequence when great idea meets great execution. CREATIVE CONSULTANTS We talk to creative directors, film makers and to clients to find out what the prob- PealiDezine lem is when it comes to execution. Is it about time? Money? Or simply about an LAYOUT Indian way of doing things? You may not like all that you read but it will make you Vinay Dominic look at an old issue afresh. -

Teen Deener Durga Pujo Bangla Class Gaaner Class Sonkirton Saraswati

Volume 40 Issue 2 May 2015 teen deener Durga Pujo bangla class gaaner class robibarer aroti natoker rehearsal Children’s Day committee odhibeshon sonkirton Saraswati Pujo Mohaloya Seminar Kali Pujo carom tournament shree ponchomee Bangasanskriti Dibos poush parbon Boi paath Seminar Dolkhela gaaner jolsa Setar o tobla Saraswati Pujo Shri ramkrishna jonmotsob Natoker rehearsal Picnic Committee odhibeshon Seminar Picnic Chhayachhobi teen deener Durga Pujo Smart club Pi day Math team Children’s Day Kali Pujo natokchorcha table tennis tournaments anandamela bangabhavan repair Picnic Wreenmukto Bangabhavan noboborsho cultural program bangla class Bangasanskriti Dibos Robibarer aroti Natoker rehearsal Kali Pujo Committee odhibeshon Shree ponchomee sonkirton teen deener Durga Pujo Mohaloya Gaaner class Seminar Jonmashtomee Children’s Day Carom tournament Poush parbon Saraswati Pujo Boi paath Shri ramkrishna jonmotsob Dolkhela Gaaner jolsa Setar o tobla teen deener Durga Pujo Seminar Dolkhela gaaner jolsa Setar o tobla Kali Pujo Shri ramkrishna jonmotsob Seminar bijoyadoshomee bangabhavan repair Wreenmukto Bangabhavan 2 Banga Sanskriti Dibas Schedule From Editor’s Desk Saturday, May 23rd, 2015 With winter behind us and spring upon Streamwood High School us it is time to enjoy sunny days, nature Registration 3:30 p.m to 6:30 p.m walks, and other outdoor activities. Greeting and Best wishes for the Bengali New Year GBM - Reorg Committee Presentatoin 3:30 p.m to 4:30 p.m 1422. Please join us to celebrate Banga San- Snacks 4:30 p.m to 5:30 p.m skriti Dibas and enjoy a nostalgic evening of Bengali culture. You can find more details of Cultural Programs 5:30 p.m to 8:30 p.m the schedule, program highlights, venue and Dinner 8:30 p.m to 10:00 p.m food in the next few pages of the newsletter. -

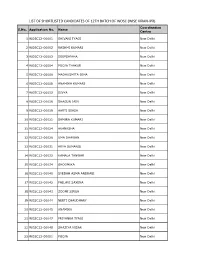

List of Shortlisted Candidates of 12Th Batch of Wosc (Wise Kiran-Ipr)

LIST OF SHORTLISTED CANDIDATES OF 12TH BATCH OF WOSC (WISE KIRAN-IPR) Coordination S.No. Application No. Name Centre 1WOSC12-00001 SHIVANI TYAGI New Delhi 2WOSC12-00002 RASHMI KUMARI New Delhi 3WOSC12-00003 DEEPSHIKHA New Delhi 4WOSC12-00004 POOJA THAKUR New Delhi 5WOSC12-00006 MADHUSMITA OJHA New Delhi 6WOSC12-00008 ANAMIKA KUMARI New Delhi 7WOSC12-00012 DIVYA New Delhi 8WOSC12-00016 SHAGUN JAIN New Delhi 9WOSC12-00019 AARTI SINGH New Delhi 10WOSC12-00021 SAMIRA KUMARI New Delhi 11WOSC12-00024 AKANKSHA New Delhi 12WOSC12-00026 UMA DHAWAN New Delhi 13WOSC12-00031 ARYA SUMANGI New Delhi 14WOSC12-00032 KAMALA TANWAR New Delhi 15WOSC12-00034 BHOOMIKA New Delhi 16WOSC12-00040 SYEDAH ASMA ANDRABI New Delhi 17WOSC12-00042 PALLAVI SAXENA New Delhi 18WOSC12-00043 ZOOMI SINGH New Delhi 19WOSC12-00044 NEETI CHAUDHARY New Delhi 20WOSC12-00045 ANAMIKA New Delhi 21WOSC12-00047 PRIYANKA TYAGI New Delhi 22WOSC12-00048 SHAZIYA NISAR New Delhi 23WOSC12-00051 POOJA New Delhi 24WOSC12-00053 NUSRAT PRAWEEN New Delhi 25WOSC12-00056 NADISH MANZOOR New Delhi 26WOSC12-00057 VIBHA BHATIA New Delhi 27WOSC12-00059 AMALA MASA New Delhi 28WOSC12-00062 NEHA SHARMA New Delhi 29WOSC12-00068 TARUNA SHARMA New Delhi 30WOSC12-00070 MEDHAVI New Delhi 31WOSC12-00074 VIJAY LAXMI New Delhi 32WOSC12-00075 RAKHI GAUNIYAL New Delhi 33WOSC12-00078 RASHMI GUPTA New Delhi 34WOSC12-00080 PREETI GUPTA New Delhi 35WOSC12-00083 MONIKA New Delhi 36WOSC12-00084 POONAM New Delhi 37WOSC12-00097 SUDHA CHINNU New Delhi 38WOSC12-00099 AZRA UNNISA New Delhi 39WOSC12-00100 RUCHI SINGHAL New -

The Domestic Is Not Free, Nov 2—10, Spotlighting the Ways Women Have Created, Challenged, and Subverted Domesticity

BAM presents Women at Work: The Domestic Is Not Free, Nov 2—10, spotlighting the ways women have created, challenged, and subverted domesticity October 9, 2018/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, November 2 through Saturday, November 10 BAM presents Women at Work: The Domestic Is Not Free, a wide-ranging series spotlighting the overlooked work women take on in the home as house-workers, caretakers, and familial partners. The Domestic Is Not Free is the third edition of the ongoing Women at Work series—following Women at Work: Labor Activism in March and Women at Work: Radical Creativity in August—and highlights the historically erased and undervalued physical and emotional labor women perform, often invisibly, every day. The series considers the myriad ways in which women around the world have challenged and subverted traditional associations between gender and domesticity. Exploring the intersections of labor, race, class, and social environment, these films embody human stories of sacrifice and endurance. BAM Cinema Department Coordinator and programmer of the series Natalie Erazo explains, “I learned early on to value the domestic space and appreciate the women around me who shaped it. I hope this series will encourage viewers to acknowledge the monotony and emotional bearing of a life often relegated to being behind the scenes.” The series opens with Ousmane Sembène’s seminal Black Girl (1966—Nov 2). Screening with short films Fannie’s Film (Woods, 1979) and Fucked Like a Star (Saintonge, 2018), these films depict black women in roles of domestic service while also giving audiences access to their inner thoughts, feelings, and struggles. -

A Weekend of Film on Partition Flyer

home box office mcr. 0161 200 1500 org home PARTITION A weekend of screenings and special events marking the 70th anniversary of the Partition of India. Qissa, 2013 FRI 9 – SUN 11 JUN HOME presents a weekend The Cloud-Capped Star Qissa of cinematic representations and responses to the events that divided India in 1947, creating first Pakistan and later Bangladesh. The season is designed to THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR (PG) ONE HOUR INTRO/ PARTITION ON enhance understanding of (MEGHE DHAKA TARA) FILM this momentous historical Sun 11 Jun, 17:00 event, as well as exploring Sat 10 Jun, 15:15 Dir Ritwik Ghatak/IN 1960/122 mins/Bengali wEng ST Tickets £4 full / £3 concs the meanings and legacies of Supriya Choudhury, Anil Chatterjee, Gyanesh Mukherjee This talk will reflect on the imaginings Partition today. Through its tale of Nita’s struggle to keep her refugee family afloat,The of Partition, notably in Indian cinema, Curated by Andy Willis, Reader Cloud-Capped Star operates as a harsh uncovering the reasons for the continued in Film Studies at the University criticism of the social and economic relative silence around such a divisive of Salford, and HOME’s Senior conditions that arose from Partition - a history, how filmmakers have responded over the years, and the contested Visiting Curator: Film. driving force in the life of celebrated filmmaker Ritwik Ghata. role film has played in the traumatic Partition is generously supported by aftermath. The talk will be supported B&M Retail. QISSA: THE TALE OF A LONELY with sequences from key films on GHOST (CTBA) + Q&A Partition. -

Unit Indian Cinema

Popular Culture .UNIT INDIAN CINEMA Structure Objectives Introduction Introducing Indian Cinema 13.2.1 Era of Silent Films 13.2.2 Pre-Independence Talkies 13.2.3 Post Independence Cinema Indian Cinema as an Industry Indian Cinema : Fantasy or Reality Indian Cinema in Political Perspective Image of Hero Image of Woman Music And Dance in Indian Cinema Achievements of Indian Cinema Let Us Sum Up Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises A 13.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit discusses about Indian cinema. Indian cinema has been a very powerful medium for the popular expression of India's cultural identity. After reading this Unit you will be able to: familiarize yourself with the achievements of about a hundred years of Indian cinema, trace the development of Indian cinema as an industry, spell out the various ways in which social reality has been portrayed in Indian cinema, place Indian cinema in a political perspective, define the specificities of the images of men and women in Indian cinema, . outline the importance of music in cinema, and get an idea of the main achievements of Indian cinema. 13.1 INTRODUCTION .p It is not possible to fully comprehend the various facets of modern Indan culture without understanding Indian cinema. Although primarily a source of entertainment, Indian cinema has nonetheless played an important role in carving out areas of unity between various groups and communities based on caste, religion and language. Indian cinema is almost as old as world cinema. On the one hand it has gdted to the world great film makers like Satyajit Ray, , it has also, on the other hand, evolved melodramatic forms of popular films which have gone beyond the Indian frontiers to create an impact in regions of South west Asia. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Indian Films on Partition of India

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Manoj Sharma, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 3, pp. 492 - 501 Date of Publication: 15th December, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.33.492501 This paper can be cited as: Sharma, M. (2017). Cinematic Representations of Partition of India. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 492-501. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. CINEMATIC REPRESENTATIONS OF PARTITION OF INDIA Dr. Manoj Sharma Assistant Professor, Modern Indian History, Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 – India [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The partition of India in August 1947 marks a watershed in the modern Indian history. The creation of two nations, India and Pakistan, was not only a geographical division but also widened the chasm in the hearts of the people. The objective of the paper is to study the cinematic representations of the experiences associated with the partition of India. The cinematic portrayal of fear generated by the partition violence and the terror accompanying it will also be examined. Films dealing with partition have common themes of displacement of thousands of masses from their homelands, being called refugees in their own homeland and their struggle for survival in refugee colonies. They showcase the trauma of fear, violence, personal pain, loss and uprooting from native place. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity

The Cinema of Satyajit Ray Between Tradition and Modernity DARIUS COOPER San Diego Mesa College PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written perrnission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/13 pt. System QuarkXpress® [mg] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cooper, Darius, 1949– The cinema of Satyajit Ray : between tradition and modernity / Darius Cooper p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in film) Filmography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0 521 62026 0 (hb). – isbn 0 521 62980 2 (pb) 1. Ray, Satyajit, 1921–1992 – Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series pn1998.3.r4c88 1999 791.43´0233´092 – dc21 99–24768 cip isbn 0 521 62026 0 hardback isbn 0 521 62980 2 paperback Contents List of Illustrations page ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Between Wonder, Intuition, and Suggestion: Rasa in Satyajit Ray’s The Apu Trilogy and Jalsaghar 15 Rasa Theory: An Overview 15 The Excellence Implicit in the Classical Aesthetic Form of Rasa: Three Principles 24 Rasa in Pather Panchali (1955) 26 Rasa in Aparajito (1956) 40 Rasa in Apur Sansar (1959) 50 Jalsaghar (1958): A Critical Evaluation Rendered through Rasa 64 Concluding Remarks 72 2. -

Paper Title (Use Style: Paper Title)

International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) ISSN: 2394-4404 Volume 7 Issue 5, May 2020 A Study On The Path- Breaking Intellectual Impact Of The Marxist Cultural Movement (1940s) Of India DR. Sreyasi Ghosh Assistant Professor and HOD of History Dept., Hiralal Mazumdar Memorial College for Women, Dakshineshwar, Kolkata, India Abstract: In history of Bengal/India, the decade of 1940s was undoubtedly an era of both trauma and triumph. The Second World War, famine, communal riot and Partition/refuge e crisis occurred during this phase but in spite of colossal loss and bloodbath the Marxist Cultural Movement/Renaissance flourished and left its imprint on various spheres such as on literature, songs, dance movements, painting and movie -making world. The All India Centre Of The Progressive Writers” Association was established under leadership of Munshi Premchand in 1936. Eminent people like Mulkraj Anand, Sajjad Jahir, Muhammad Ashraf and Bhabani Bhattacharyya were gradually involved with that platform which achieved immense moral support from Rabindranath Tagore, Sarojini Naidu, Ramananda Chattopadhyay, and Saratchandra Chattopadhyay. Nareshchandra Sengupta became President when its branch for Bengal was founded on June 25, 1936. Actually the Anti-Fascist International Association Of Writers” For The Defence Of Culture, established in Paris (1935) through effort of Romain Rolland and Gorkey, made path for the Marxist cultural Movement of India. Indian Movement had important milestones in its history of development such as establishment of Youth Cutural Institute (1940), Organisation Of The Friends Of The Soviet Union (1941), The Anti-Fascist Writers” And Artists” Association (1942) and The Indian People”s Theatre Association (I.P.T.A- 1943) etc.