Local Peace Processes in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

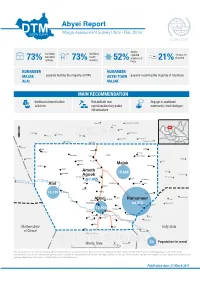

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

View: S/2021/322

United Nations S/2021/322 Security Council Distr.: General 1 April 2021 Original: English Letter dated 1 April 2021 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to refer to paragraph 31 of resolution 2550 (2020), in which the Security Council requested that I hold joint consultations with the Governments of the Sudan, South Sudan and Ethiopia, as well as other relevant stakeholders, to discuss an exit strategy for the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) and develop options for its responsible drawdown and exit. I further refer to the request of the Security Council that I report no later than 31 March 2021, elaborating on those options, which should prioritize the safety and security of civilians living in Abyei, account for the stability of the region and include an option for a responsible drawdown and exit of UNISFA that is not limited by implementation of the 2011 agreements. Pursuant to the above request, my Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa undertook consultations in February and March 2021. Consultations with the transitional Government of the Sudan took place in Khartoum through discussions with the Chair of the Sovereign Council, Lieutenant General Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan; the Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok; the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Mariam Al-Sadiq Al-Mahdi; the Minister of Defence, Lieutenant General Yassin Ibrahim Yassin; and representatives of the Abyei Joint Oversight Committee. Owing to the severe impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in South Sudan, consultations with the Government of South Sudan were held remotely and in writing through the Minister for Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Beatrice Khamisa Wani- Noah, and the Minister of East African Community Affairs, Deng Alor, holder of the Abyei portfolio. -

Survey of South Sudan Public Opinion April 24 to May 22, 2013 Survey Methodology

Survey of South Sudan Public Opinion April 24 to May 22, 2013 Survey Methodology • The International Republican Institute (IRI) undertook a public opinion poll in all 10 states of South Sudan. Training of the poll researchers was performed by Opinion Research Business (ORB), an international opinion research firm. Fieldwork management, analysis, supervision and execution were done by IRI under critical guidance of ORB. • Data was collected via face-to-face interviews from April 24 – May 22, 2013. • The population studied was adults ages 18 and older. A representative random sample was designed based on the latest population estimates reported in the 2010 Statistical Yearbook for South Sudan. • The survey employed probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling methodology. The population of South Sudan was stratified first at the region level and then by the state level. Within each state, IRI and ORB then selected counties. This was done by creating a multi-stage probability sample. Enumeration areas within each county were selected using PPS; households within each enumeration area were then identified using a random walk method, the days code and a skip pattern; respondents were randomly chosen within households using a Kish grid. Every other interview was conducted with a female to try to achieve 50 percent gender parity. • The questionnaire was translated into Bari, Classical Arabic, Dinka, English, Juba Arabic and Nuer (portions of the questionnaire were orally translated into other languages by the interviewer). 2 Survey Methodology • The margin of error is +/- 1.9 percent. The margin of error for subsets (i.e. age/education/tribes/ etc.) is significantly higher and should be treated as indicative only. -

Political Repression in Sudan

Sudan Page 1 of 243 BEHIND THE RED LINE Political Repression in Sudan Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch Copyright © May 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 96-75962 ISBN 1-56432-164-9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was researched and written by Human Rights Watch Counsel Jemera Rone. Human Rights Watch Leonard H. Sandler Fellow Brian Owsley also conducted research with Ms. Rone during a mission to Khartoum, Sudan, from May 1-June 13, 1995, at the invitation of the Sudanese government. Interviews in Khartoum with nongovernment people and agencies were conducted in private, as agreed with the government before the mission began. Private individuals and groups requested anonymity because of fear of government reprisals. Interviews in Juba, the largest town in the south, were not private and were controlled by Sudan Security, which terminated the visit prematurely. Other interviews were conducted in the United States, Cairo, London and elsewhere after the end of the mission. Ms. Rone conducted further research in Kenya and southern Sudan from March 5-20, 1995. The report was edited by Deputy Program Director Michael McClintock and Human Rights Watch/Africa Executive Director Peter Takirambudde. Acting Counsel Dinah PoKempner reviewed sections of the manuscript and Associate Kerry McArthur provided production assistance. This report could not have been written without the assistance of many Sudanese whose names cannot be disclosed. CONTENTS -

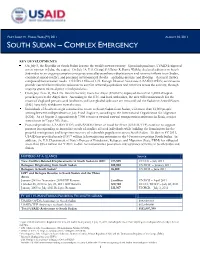

South Sudan Complex Emergency Fact

FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2011 AUGUST 10, 2011 SOUTH SUDAN – COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS On July 9, the Republic of South Sudan became the world’s newest country. Upon independence, USAID designated a new mission in Juba, the capital. On July 14, U.S. Chargé d’Affaires R. Barrie Walkley declared a disaster in South Sudan due to an ongoing complex emergency caused by population displacement and returnee inflows from Sudan, continued armed conflict, and perennial environmental shocks—including drought and flooding—that may further compound humanitarian needs. USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) continues to provide essential humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected populations and returnees across the country, through ongoing grants initiated prior to independence. From July 16 to 31, the U.N. Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) deployed more than 1,600 Ethiopian peacekeepers to the Abyei Area. According to the U.N. and local authorities, the area will remain unsafe for the return of displaced persons until landmines and unexploded ordnance are removed and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have fully withdrawn from the area. Individuals of Southern origin continued to return to South Sudan from Sudan, with more than 12,000 people arriving between independence on July 9 and August 8, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). As of August 3, approximately 7,500 returnees awaited onward transportation assistance in Renk, a major transit town in Upper Nile State. Post-independence, USAID/OFDA and USAID’s Office of Food for Peace (USAID/FFP) continue to support partners in responding to immediate needs of conflict-affected individuals while building the foundations for the peaceful reintegration and long-term recovery of vulnerable populations across South Sudan. -

Summary Corruption and Anti-Corruption in Sudan

www.transparency.org www.cmi.no Corruption and anti-corruption in Sudan Query Could you please provide an overview of the nature and impact of corruption in Sudan? Does it affect SMEs significantly? Do foreign investors incur additional costs? Are basic services impacted by large diversions? Purpose challenges that affect both conflict torn and resource rich countries, including fragile state institutions, low The agency is currently undertaking a piece of work to administrative capacity, weak systems of checks and design our response to corruption in the new (post- balance, and blurred distinctions between the state and secession) Sudan. ruling party. The secession of South Sudan in July 2011 brings new economic and political challenges. Content Corruption permeates all sectors, and manifests itself 1. Overview of corruption in Sudan through various forms, including petty and grand 2. Anti-corruption efforts in Sudan corruption, embezzlement of public funds, and a system 3. References of political patronage well entrenched within the fabrics of society. Evidence of the impact of corruption is scarce and concealed by the country’s economic and Caveat political instability. Nevertheless, there is evidence that There is little data and research available on the patronage has a negative impact on small and medium country’s state of governance and on corruption, sized enterprises. Also, corruption in the police and particularly on its impact. The majority of recent studies security forces undermines internal security and allows have focused on the challenges faced by South Sudan, abuses of civil and political rights. The lack of so are not helpful in looking at Sudan. -

1Baugust 21, 2019

EAST AFRICA Seasonal Monitor August 21, 2019 Average to above-average rainfall in northern and western sectors favorable for cropping conditions KEY MESSAGES • Figure 1. CHIRPS preliminary rainfall performance as a June-September rainfall performance remained average to percent of normal (1981-2010), July 11 – August 10, 2019 above-average from early July to early August in unimodal areas. This has sustained largely favorable cropping conditions across northern and western agricultural zones of East Africa. • Persistent, heavy rainfall led to reports of flooding in several regions of Sudan, Ethiopia, and South Sudan as of early August. Worst-affected areas include in Khartoum, Sennar, and west Darfur states in Sudan; Afar and northwest Amhara region in Ethiopia; and Northern Bahr el Ghazal and Jonglei states of South Sudan. More rain is forecast in coming weeks. • The eastern Horn and Tanzania remained seasonally sunny but atypically hotter than normal, which has accelerated declines in water and pasture availability in pastoral areas of Kenya, parts of eastern Ethiopia, and central and southern Somalia. • There is increased concern for post-harvest maize losses, for the on-going harvest and drying in parts of eastern Uganda and western Kenya, as sustained moderate to heavy rains are forecast this month. Source: FEWS NET/Climate Hazards Center SEASONAL PROGRESS Figure 2. eMODIS/NDVI percent of normal (2007-2016), Rainfall performance from July 11th to August 10th was broadly August 1-10, 2019 average across the northern and western sectors of the region, though localized areas received well above-average rainfall amounts. Unimodal rainfall-dependent areas include Sudan, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, and western Kenya (Figure 1). -

Repression Continues in Northern Sudan

November 1994 Vol. 6, No. 9 SUDAN "IN THE NAME OF GOD" Repression Continues in Northern Sudan CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................3 II. A NUBAN DIARY.....................................................................................................................6 The Destruction of Sadah..................................................................................................16 The Burning of Shawaya...................................................................................................17 III. THE INTERNALLY DISPLACED .........................................................................................18 Forcible Displacement From Khartoum in 1994...............................................................19 Displaced Boys Rounded Up And Interned Without Due Process....................................20 IV. CONTINUING PATTERNS OF VIOLATIONS OF RIGHTS .............................................23 Arbitrary Arrest and Detention..........................................................................................24 Torture ..............................................................................................................................26 Continued Suppression of Free Assembly, Opposition Parties, and Trade Unions..........31 Silencing the Free Press ....................................................................................................33 V. RESHAPING THE LAW........................................................................................................35 -

C the Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan

C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons (from State Ministries of Livestock and Fishery Industries and FAO South Sudan Office) for collecting field data from the sample counties in nine of the ten States of South Sudan: Angelo Kom Agoth; Makuak Chol; Andrea Adup Algoc; Isaac Malak Mading; Tongu James Mark; Sebit Taroyalla Moris; Isaac Odiho; James Chatt Moa; Samuel Ajiing Uguak; Samuel Dook; Rogina Acwil; Raja Awad; Simon Mayar; Deu Lueth Ader; Mayok Dau Wal and John Memur. The authors also extend their special thanks to Erminio Sacco, Chief Technical Advisor and Dr Abdal Monium Osman, Senior Programme Officer, at FAO South Sudan for initiating this study and providing the necessary support during the preparatory and field deployment phases. DISCLAIMER FAO South Sudan mobilized a team of independent consultants to conduct this study. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. COMPOSITION OF STUDY TEAM Yacob Aklilu Gebreyes (Team Leader) Gezu Bekele Lemma Luka Biong Deng Shaif Abdullahi i C The Impact of Conflict on the Livestock Sector in South Sudan TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...I ABBREVIATIONS ..................................................................................................................................................... VI NOTES .................................................................................................................................................................. -

The 28 States System in South Sudan

The 28 States System in South Sudan Briefing Note by the Stimson Center | August 9, 2016 The recent violence in Juba between the forces of President Salva Kiir and former First Vice President Riek Machar demonstrated the fragility of South Sudan’s peace and the critical role that the international community is playing in holding the country back from the brink of renewed civil war. But the simultaneous surge in violence in Wau highlighted the daunting fact that the national-level conflict is not the only challenge for the international community in South Sudan. The country is plagued by a diverse set of local-level conflicts that interact in different ways and to different extents with the national crisis. Many of these local conflicts have been exacerbated by the Kiir faction’s unilateral introduction of the 28 states system. In the context of heightened tribal tensions, shifting political loyalties, and increased competition over power and resources in a deteriorating economy, this system could cause significant conflict and instability. As the Juba crisis unfolds and the 2015 peace agreement appears increasingly disregarded, national and international actors are considering a range of options for creating sustainable peace. This briefing note is intended to inform the debate over how to support stability in South Sudan by examining the 28 states system and its implications for security and governance. Key Points . The 28 states system is causing considerable tension at the national level and is also affecting local conflict dynamics across the country. Former Upper Nile and Western Bahr el Ghazal States are two areas where the 28 states system has already caused significant violence.