CPE South Sudan Evaluation Report Volume II Annexes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EOI Mission Template

United Nations Nations Unies United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) South Sudan REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) This notice is placed on behalf of UNMISS. United Nations Procurement Division (UNPD) cannot provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of contents of furnished information; and is unable to answer any enquiries regarding this EOI. You are therefore requested to direct all your queries to United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) using the fax number or e-mail address provided below. Title of the EOI: Provision of Refrigerant Gases to UNMISS in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan Date of this EOI: 10 January 2020 Closing Date for Receipt of EOI: 11 February 2020 EOI Number: EOIUNMISS17098 Chief Procurement Officer Unmiss Hq, Tomping Site Near Juba Address EOI response by fax or e-mail to the Attention of: International Airport, Room No 3c/02 Juba, Republic Of South Sudan Fax Number: N/A E-mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] UNSPSC Code: 24131513 DESCRIPTION OF REQUIREMENTS PD/EOI/MISSION v2018-01 1. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) has a requirement for the provision of Refrigerant Gases in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan and hereby solicits Expression of Interest (EOI) from qualified and interested vendors. SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS / INFORMATION (IF ANY) Conditions: 2. Interested service providers/companies are invited to submit their EOIs for consideration by email (preferred), courier or by hand delivery as indicated below. -

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

Communities Tackling Small Arms and Light Weapons in South Sudan Briefing

Briefing July 2018 Communities tackling small arms and light weapons in South Sudan Lessons learnt and best practices Introduction The proliferation and misuse of small arms and light Clumsy attempts at forced disarmament have created fear weapons (SALW) is one of the most pervasive problems and resentment in communities. In many cases, arms end facing South Sudan, and one which it has been struggling up recirculating afterwards. This occurs for two reasons: to reverse since before independence in July 2011. firstly, those carrying out enforced disarmaments are – either deliberately or through negligence – allowing Although remoteness and insecurity has meant that seized weapons to re-enter the illicit market. Secondly, extensive research into the exact number of SALW in there have been no simultaneous attempts to address the circulation in South Sudan is not possible, assessments of demand for SALW within the civilian population. While the prevalence of illicit arms are alarming. conflict and insecurity persists, demand for SALW is likely to remain. Based on a survey conducted in government controlled areas only, the Small Arms Survey estimated that between In April 2017, Saferworld, with support from United 232,000–601,000 illicit arms were in circulation in South Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), launched a project Sudan in 20161. It is estimated that numbers of SALW are to identify and improve community-based solutions likely to be higher in rebel-held areas. to the threats posed by the proliferation and misuse of SALW. The one-year pilot project aimed to raise Estimates also vary from state to state within South awareness among communities about the dangers of Sudan. -

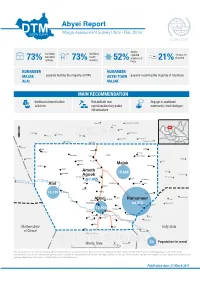

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the Market of Mayen Rual South Sudan Customary Authorities Project

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT WARTIME TRADE AND THE RESHAPING OF POWER IN SOUTH SUDAN LEARNING FROM THE MARKET OF MAYEN RUAL SOUTH SUDAN customary authorities pROjECT Wartime Trade and the Reshaping of Power in South Sudan Learning from the market of Mayen Rual NAOMI PENDLE AND CHirrilo MADUT ANEI Published in 2018 by the Rift Valley Institute PO Box 52771 GPO, 00100 Nairobi, Kenya 107 Belgravia Workshops, 159/163 Marlborough Road, London N19 4NF, United Kingdom THE RIFT VALLEY INSTITUTE (RVI) The Rift Valley Institute (www.riftvalley.net) works in eastern and central Africa to bring local knowledge to bear on social, political and economic development. THE AUTHORS Naomi Pendle is a Research Fellow in the Firoz Lalji Centre for Africa, London School of Economics. Chirrilo Madut Anei is a graduate of the University of Bahr el Ghazal and is an emerging South Sudanese researcher. SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT RVI’s South Sudan Customary Authorities Project seeks to deepen the understand- ing of the changing role of chiefs and traditional authorities in South Sudan. The SSCA Project is supported by the Swiss Government. CREDITS RVI EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Mark Bradbury RVI ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATIONS: Cedric Barnes RVI SOUTH SUDAN PROGRAMME MANAGER: Anna Rowett RVI SENIOR PUBLICATIONS AND PROGRAMME MANAGER: Magnus Taylor EDITOR: Kate McGuinness DESIGN: Lindsay Nash MAPS: Jillian Luff,MAPgrafix ISBN 978-1-907431-56-2 COVER: Chief Morris Ngor RIGHTS Copyright © Rift Valley Institute 2018 Cover image © Silvano Yokwe Alison Text and maps published under Creative Commons License Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Available for free download from www.riftvalley.net Printed copies are available from Amazon and other online retailers. -

Survey of South Sudan Public Opinion April 24 to May 22, 2013 Survey Methodology

Survey of South Sudan Public Opinion April 24 to May 22, 2013 Survey Methodology • The International Republican Institute (IRI) undertook a public opinion poll in all 10 states of South Sudan. Training of the poll researchers was performed by Opinion Research Business (ORB), an international opinion research firm. Fieldwork management, analysis, supervision and execution were done by IRI under critical guidance of ORB. • Data was collected via face-to-face interviews from April 24 – May 22, 2013. • The population studied was adults ages 18 and older. A representative random sample was designed based on the latest population estimates reported in the 2010 Statistical Yearbook for South Sudan. • The survey employed probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling methodology. The population of South Sudan was stratified first at the region level and then by the state level. Within each state, IRI and ORB then selected counties. This was done by creating a multi-stage probability sample. Enumeration areas within each county were selected using PPS; households within each enumeration area were then identified using a random walk method, the days code and a skip pattern; respondents were randomly chosen within households using a Kish grid. Every other interview was conducted with a female to try to achieve 50 percent gender parity. • The questionnaire was translated into Bari, Classical Arabic, Dinka, English, Juba Arabic and Nuer (portions of the questionnaire were orally translated into other languages by the interviewer). 2 Survey Methodology • The margin of error is +/- 1.9 percent. The margin of error for subsets (i.e. age/education/tribes/ etc.) is significantly higher and should be treated as indicative only. -

SOUTH SUDAN Monthly Market Price Monitoring Bulletin October 2019

SOUTH SUDAN Monthly Market Price Monitoring Bulletin October 2019 Highlights − In October 2019, there was a general decrease in the average price of a standard food basket, mainly due to lower import prices of key stable food from Uganda, in line with seasonal trends; − In Wau, Kuajok, Torit, Mingkaman and Aweil, the purchasing power improved for households that are depending on livestock keeping as their main source of income; − Severe flooding caused 36 percent increase in diesel and petrol prices in Bunj market; − Prices of staple foods are expected to drop further in the coming two-three months if the security situation remain stable and as the harvest comes into the market. Macroeconomic challenges In October 2019, the average exchange rate of South Sudanese Pounds (SSP) to United States Dollars (USD) in the parallel market was SSP 313, which is nearly double of the official rate of SSP 162 per USD. Despite both exchange rates remaining stable since last month, the parallel market rate has seen a high year-on-year increase of 45 percent compared to only eight percent for the official rate. This increased the gap between the two exchange rates. South Sudan depends on import of vital staple food commodities including cereals, which comprise the most important part of the diet for the population. However, monetary challenges including lack of ability to secure enough USD for imports cause severe market constraints and negatively affect the availability of basic commodities in the local markets. Despite an increase in production and export of crude oil by 20 percent starting from February 2019, following the cessation of hostilities in Unity and Upper Nile counties, the formal market access to USD remains low. -

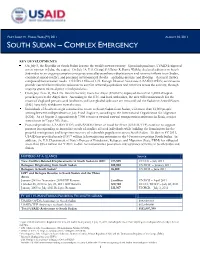

South Sudan Complex Emergency Fact

FACT SHEET #1, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2011 AUGUST 10, 2011 SOUTH SUDAN – COMPLEX EMERGENCY KEY DEVELOPMENTS On July 9, the Republic of South Sudan became the world’s newest country. Upon independence, USAID designated a new mission in Juba, the capital. On July 14, U.S. Chargé d’Affaires R. Barrie Walkley declared a disaster in South Sudan due to an ongoing complex emergency caused by population displacement and returnee inflows from Sudan, continued armed conflict, and perennial environmental shocks—including drought and flooding—that may further compound humanitarian needs. USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) continues to provide essential humanitarian assistance to conflict-affected populations and returnees across the country, through ongoing grants initiated prior to independence. From July 16 to 31, the U.N. Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) deployed more than 1,600 Ethiopian peacekeepers to the Abyei Area. According to the U.N. and local authorities, the area will remain unsafe for the return of displaced persons until landmines and unexploded ordnance are removed and the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) have fully withdrawn from the area. Individuals of Southern origin continued to return to South Sudan from Sudan, with more than 12,000 people arriving between independence on July 9 and August 8, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). As of August 3, approximately 7,500 returnees awaited onward transportation assistance in Renk, a major transit town in Upper Nile State. Post-independence, USAID/OFDA and USAID’s Office of Food for Peace (USAID/FFP) continue to support partners in responding to immediate needs of conflict-affected individuals while building the foundations for the peaceful reintegration and long-term recovery of vulnerable populations across South Sudan. -

South Sudan Situation Map (November 2014)

South Sudan situation map (November 2014) Total estimated number of IDPs: 1,439,250 7.3 million (15 November) people targeted for assistance 202 in 180 locations 3.8 million people at risk 213 Total estimated number of IDPs - countrywide for 12 months, January to Dec2014 (as per the Crisis Response Plan). Manyo 102,265 in UNMISS PoC area (18 November): 227 in 8 bases 319 Total number of people assisted: 3.5 million 289 - with some form of assistance - includes in-country 246,433 refugees Renk Total estimated number of crisis-displaced who 198,531 207 Note: Displacement figures are based on reports from have gone back (15 November): in 12 locations partners on the ground. The majority of them have not SUDAN been verfied. Verfication of the figures is work in progress Total number of South Sudanese 107,131 217 Melut 216 299 474,769 108 290 displaced to neighbouring countries 67 206 after 15Dec (18 November): in 4 countries ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Fashoda ! 139 ! ! 82 ! ! 136 ! ! 137 Maban ! ! ! ! ! ! 80 ! 291 ! ! ! 199 ! ! 140 81 Upper Nile ! Abyei ! ! ! 125 ! ! Pariang ! ! Malakal ! 200 ! ! ! ! ! ! region ! 138 ! ! ! ! Abiemnhom 135 ! 93 ! 63 ! 305 ! ! 1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! P ! ! Unity 288 Malakal ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 36 Baliet Aweil N. 120 Bentiu 92 69 255 239 263 302 Aweil E. 89 P Guit 98 Longochuk301 Twic Panyikang 91 73 237 Rubkona267 254 304 285 225 37 Canal/Pigi 265 90 74 76 236 253 Luakpiny/Nasir Aweil W2.68 308 300 61 246 75 Mayom 100 247 Leer Fangak 252 P Aweil Ulang Maiwut 245 Gogrial E. 104 144 249 310 Nyirol 159 Raga 70198 307 Aweil S. -

Amplifying People's Voices to Contribute to Peace and Resilience

BRIEF / MARCH 2021 Amplifying people’s voices to contribute to peace and resilience in Warrap, South Sudan Warrap state is in the northern part of South Sudan. The clans in the state were high. The governor toured Tonj state borders Unity state to the north-east, Lakes to the North, Tonj South and Gogrial East counties with peace east, Northern Bahr el Ghazal to the north and Western and reconciliation messages and pledged to work closely Bahr el Ghazal to the south. The state is home to the with peace actors in the state. However, violent conflicts Dinka and Bongo ethnic communities. among rival clans in Greater Tonj have intensified, leading to Bona Panek – who was seen as having a ‘soft’ approach The main sources of livelihoods for people in Warrap to communal conflict – being replaced by General Aleu include cattle rearing and small-scale farming, as well Ayieny on 28 January 2021. as beekeeping and wild honey harvesting among the Bongo community in Tonj South County. Cattle rearing Warrap, like many other parts of South Sudan, is is associated with numerous challenges such as cattle experiencing tough economic times. There are multiple raids, stealing, and the need to migrate to neighbouring factors at play, such as political instability in the state communities in search of food and for grazing lands and and in the country, poor road connections, persistent water for animals. In recent years, Warrap has experienced intercommunal violence, and hyperinflation compounded unprecedented intercommunal conflicts, violent cattle by a decline in the purchasing power of the South raiding fuelled by the proliferation of small arms and light Sudanese pound. -

SOUTH SUDAN Total Population by County

SOUTH SUDAN Total population by county Manyo 77,009 Renk 189,061 SUDAN Melut 126,691 Malakal Fashoda Maban Pariang 74,772 54,263 Abyei region 127,959 UPPER NILE Panyikang 190,398 Abiemnhom ! 55,593 Rubkona 65,294 Malakal Baliet Aweil North Aweil East 333,412 56,348 ! 164,383 336,473 Twic Mayom Guit Longochuk Bentiu Canal/Pigi 263,824 152,879 68,179 Fangak 72,633 Raja Aweil West 103,828 Luakpiny/ Gogrial East 191,782 Nasir 58,073 198,885 ! 127,687 Aweil Gogrial 286,628 Maiwut Aweil South UNITY NORTHERN West Koch Ulang 128,913 138,486 Tonj Nyirol 317,972 96,257 137,691 BAHR EL North Ayod 138,777 GHAZAL ! Kuajok 256,629 189,295 Aweil Centre Mayendit Leer 74,120 WARRAP 69,075 75,769 Tonj East ETHIOPIA JONGLEI Akobo ! 179,909 WESTERN BAHR Wau Rumbek Duk 221,022 North Panyijiar Uror EL GHAZAL Jur 194,183 Wau River 70,949 117,105 191,141 CENTRAL 312,336 276,320 Rumbek Pochalla AFRICAN Cueibet Centre Twic East 77,474 Tonj 178,855 210,348 121,089 REPUBLIC South Yirol East 116,467 Rumbek ! Rumbek East 156,459 Bor South 170,302 Nagero 331,333 Yirol West LAKES Pibor International boundary 37,740 170,217 222,297 Awerial ! Bor State boundary Wulu Tambura 86,885 136,232 Mvolo County boundary 116,202 73,373 Undetermined boundary Terekeka WESTERN 252,096 Lafon Abyei region Mundri EQUATORIA Kapoeta EASTERN Ibba West Mundri 153,028 !^ Country capital East North EQUATORIA Ezo 64,801 48,457 97,644 153,304 129,508 Maridi Juba Kapoeta East ! State capital Yambio 107,613 509,958 165,518 164,427 Juba Total population per county Nzara !^ 81,561 Yambio Kapoeta 1-50,000 ! CENTRAL South 99,739 Lainya EQUATORIA ! Torit 50,001-100,000 Yei Budi 294,818 110,939 Torit 102,231 DEMOCRATIC 61,440 100,001-200,000 Ikotos REPUBLIC OF Kajo-keji Magwi KENYA 200,001-300,000 104,238 226,983 258,402 THE CONGO Morobo 300,001-500,000 113,186 UGANDA 0 50 100 km The administrative boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.