Genomic Designing for Climate Smart Finger Millet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form 104 School Lunch Meal Pattern Grains Fact Sheet 6.2015.Pub

School Lunch Meal Pattern Grains Fact Sheet Form 104 All grains must be Whole Grain-Rich (WGR) June 2015 Whole GrainGrain----RichRich (WGR) Barley Wheat (Red) Dehulled barley Bulgur (cracked wheat) DehulledDehulled----barleybarley flour Bromated wholewhole----wheatwheat flour Whole barley Cracked wheat or crushed wheat WholeWhole----barleybarley flakes Entire wheat flour WholeWhole----barleybarley flour Graham flour Whole grain barley Sprouted wheat WholeWhole----graingrain barley flour Sprouted wheat berries Stone ground wholewhole----wheatwheat flour Brown Rice Toasted crushed whole wheat Brown rice Wheat berries Brown rice flour Whole bulgur Whole durum flour Corn Whole durum wheat flour Whole corn WholeWhole----graingrain bulgur WholeWhole----corncorn flour WholeWhole----graingrain wheat Whole cornmeal WholeWhole----wheatwheat flour WholeWhole----graingrain corn flour WholeWhole----wheatwheat pastry flour WholeWhole----graingrain grits Whole wheat flakes Oats Wheat(White) Oat groats Whole white wheat Oatmeal or rolled oats Whole white wheat flour Whole oats WholeWhole----oatoat flour Wild Rice Rye Wild rice Whole rye WildWild----ricerice flour Rye berries WholeWhole----ryerye flour WholeWhole----ryerye flakes Less Common Grains To be whole grains “whole” must be listed before the grain name Amaranth Buckwheat Einkorn Emmer (faro) Kamut ® Millet Quinoa Sorghum (milo) Spelt Teff Triticale Grain Facts: To be considered WGR, the product must contain 100% whole grain OR be at least 50 Form 104 percent whole grains, any remaining grains must be enriched and any non-creditable June 2015 grains must be less than 2 percent (¼ ounce equivalent) of the product formula. For more information, see Whole Grain Resource for NSLP and SBP Manual No more than two grain-based desserts can be credited per week. -

The Economic Consequences of Striga Hermonthica in Maize Production in Western Kenya

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Economics The economic consequences of Striga hermonthica in maize production in Western Kenya Jenny Andersson Marcus Halvarsson Independent project ! 15 hec ! Basic level Agricultural Programme- Economics and Management Degree thesis No 669 ! ISSN 1401-4084 Uppsala 2011 The economic consequences of Striga in crop production in Western Kenya Jenny Andersson Marcus Halvarsson Supervisor: Hans Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Economics Assistant supervisor: Kristina Röing de Nowina, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Department of Soil and Environment Examiner: Karin Hakelius, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Economics Credits: 15 hec Level: Basic C Course title: Business Administration Course code: EX0538 Programme/Education: Agricultural Programme-Economics and Management Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2011 Name of Series: Degree project No: 669 ISSN 1401-4084 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key words: Africa, farming systems, maize, striga Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Economics Acknowledgements This MFS project was funded by Sida and was a part of an on-going research project in Western Kenya led by Kristina Röing de Nowina. We appreciate the opportunity given to us to be a part of it. We would like to thank all farmers who were interviewed and made it possible to establish this report. We would also like to thank our supervisors Hans Andersson and Kristina Röing de Nowina for their support. Nairobi May 2011 Jenny Andersson and Marcus Halvarsson Summary Kenya is a country of 35 million people and is situated in Eastern Africa. -

Combined Control of Striga Hermonthica and Stemborers by Maize–Desmodium Spp

ARTICLE IN PRESS Crop Protection 25 (2006) 989–995 www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Combined control of Striga hermonthica and stemborers by maize–Desmodium spp. intercrops Zeyaur R. Khana,Ã, John A. Pickettb, Lester J. Wadhamsb, Ahmed Hassanalia, Charles A.O. Midegaa aInternational Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), P.O. Box 30772, Nairobi 00100, Kenya bBiological Chemistry Division, Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire AL5 2JQ, UK Accepted 4 January 2006 Abstract The African witchweed (Striga spp.) and lepidopteran stemborers are two major biotic constraints to the efficient production of maize in sub-Saharan Africa. Previous studies had shown the value of intercropping maize with Desmodium uncinatum in the control of both pests. The current study was conducted to assess the potential role of other Desmodium spp., adapted to different agro-ecologies, in combined control of both pests in Kenya. Treatments consisted of intercropped plots of a Striga hermonthica- and stemborer-susceptible maize variety and one Desmodium sp. or cowpea, with a maize monocrop plot included as a control. S. hermonthica counts and stemborer damage to maize plants were significantly reduced in maize–desmodium intercrops (by up to 99.2% and 74.7%, respectively) than in a maize monocrop and a maize–cowpea intercrop. Similarly, maize plant height and grain yields were significantly higher (by up to 103.2% and 511.1%, respectively) in maize–desmodium intercrops than in maize monocrops or maize–cowpea intercrops. These results confirmed earlier findings that intercropping maize with D. uncinatum effectively suppressed S. hermonthica and stemborer infestations in maize resulting in higher crop yields. -

Whole and Enriched Grains CACFP Reference Sheet

OSPI CNS Child and Adult Care Food Program Reference Sheet Whole and Enriched Grains Whole and enriched grains are a part of identifying Whole Grain-Rich (WGR) items. There are several methods to identify WGR items. Please view the Grain Requirements in the CACFP Reference Sheet for more information. Whole Grains: Amaranth Sprouted einkorn Amaranth flour Sprouted spelt Brown rice Sprouted whole rye Buckwheat Sprouted whole wheat Buckwheat flour Steel cut oats Buckwheat groats Teff Bulgur Teff flour Cracked wheat Triticale Graham flour Triticale flour Instant oatmeal Wheat berries Millet Wheat groats Millet flour Whole durum flour Oat groats Whole einkorn berries Old fashioned oats Whole grain corn Quick cooking oats Whole grain corn flour Quinoa Whole grain einkorn flour Rye groats Whole grain oat flour Sorghum Whole grain spelt flour Sorghum flour Whole grain wheat flakes Spelt berries Whole rye flour Sprouted brown rice Whole wheat flour Sprouted buckwheat Wild rice Whole corn Brans and Germs: Corn bran Rye bran Oat bran Wheat bran Rice bran Wheat germ Enriched Grains: Enriched bromated flour Enriched rice Enriched corn flour Enriched rice flour Enriched durum flour Enriched rye flour Enriched durum wheat Enriched wheat flour flour Enriched white flour OSPI CNS November 2018 OSPI CNS Child and Adult Care Food Program Reference Sheet Disregarded Ingredients – May be ignored (typically presented in small amounts) Corn dextrin Tapioca starch Corn starch Wheat dextrin Modified -

Whole Grain Goodness

Nutrition Know-How Child Health Specialty Clinics Whole Grain Goodness What is a whole grain? A whole grain food has all three parts of the grain, and each part has different vitamins and minerals that work together to provide nutrition. Many people only think of wheat and other bread products when they hear the word “grain,” but there are many foods that contain whole grains. Why do whole grains matter? Whole grains are higher in fiber, iron and vitamins than processed grains like white flour. Fiber can help your child pass bowel movements, and iron and vitamins are very important for a child’s growth and development. People who eat more whole grains are less likely to struggle with their weight and other serious health conditions like colon cancer. How much whole grain does my child need? This depends on your child’s age and size. A good guide is to make at least half of your child’s grain servings whole grain. For example, if your child eats 6 servings of grain, at least 3 of those servings should be whole grain. How do I know if a food is whole grain? Look for the words “whole grain” on the package. Foods with at least 51% whole grain will have a special label on them like the one shown at the top of this page. You can also check the ingredients; to be a whole grain product a food should have a whole grain listed as the first ingredient. A whole grain bread will have “whole wheat flour” as the first ingredient. -

Witchweed Eradication Program in North and South Carolina

United States Department of Agriculture Witchweed Eradication Marketing and Regulatory Program in North and Programs South Carolina Environmental Assessment, April 2020 Witchweed Eradication Program in North and South Carolina Environmental Assessment, April 2020 Agency Contact: Anne Lebrun Policy Manager Plant Protection and Quarantine, Plant Health Programs Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Road, Unit 60 Riverdale, MD 20737–1232 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program,or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. -

Gluten-Free Grains

Gluten-Free Grains Amaranth Updated February 2021 Buckwheat The gluten-free diet requires total avoidance of the grains wheat, barley, rye and all varieties and hybrids of these grains, such as spelt. However, there are many wonderful gluten-free grains* to enjoy. Cornmeal, Amaranth Polenta, Grits, Once the sacred food of the Aztecs, amaranth is high in protein, calcium, iron, and fiber. Toasting this tiny grain before cooking brings out its nutty flavor. Hominy Makes a delicious, creamy hot breakfast cereal. Serve with fruit of choice on top and/or a touch of maple syrup. Millet Rice Rice comes in many varieties: short grain, long grain, jasmine and basmati to name a Oats few. Long grain rice tends to be fluffier while short grain rice is stickier. Rice also comes in various colors: black, purple, brown, and red. These colorful un-refined rices contribute more nutritional benefits than does refined white rice and have subtly unique flavors and Quinoa textures too. Wild rice is another different and delicious option. Versatile rice leftovers can go in many directions. Add to salads or sautéed vegetables; Rice make rice pancakes or rice pudding; season and use as filling for baked green peppers or winter squash. Sorghum Buckwheat Despite the name, buckwheat is a gluten-free member of the rhubarb family. Roasted buckwheat is called kasha. Buckwheat is high in B Vitamins, fiber, iron, magnesium, Teff phosphorous and zinc. Buckwheat has an earthy, nutty, slightly bitter taste. Experiment with using the cooked grain (buckwheat “groats”, or “kasha” which is the toasted version) as you would rice. -

Protecting Minnesota's Wild Rice Lakes

Protecting Minnesota’s wild rice lakes June 2015 Snapshots Minnesota is the epicenter of the world’s natural wild rice. Protected, undeveloped shoreland is important to preserving sensitive wild rice lakes for current and future generations of wildlife and outdoor enthusiasts. Although once found throughout most of the state, today, the heart of the state’s wild rice acreage falls within eleven counties: Aitkin, Becker, Beltrami, Carlton, Cass, Clearwater, Crow Wing, Hubbard, Itasca, St. Louis and Wadena. Wild rice is important both socially and culturally in Minnesota. Wild rice also provides important ecological benefits. Wild rice shoreland encompasses a complex of shallow lakes, rivers, and shallow bays of deeper lakes that support rice and provide some of the most important habitat for wetland- dependent wildlife species in Minnesota. Wild rice habitat is especially important to Minnesota’s migrating and breeding waterfowl and provides Minnesotans with unique recreation opportunities: hunting waterfowl and harvesting the rice itself for food. Wild rice also improves and protects water A young man harvests wild quality by keeping soil and nutrients in place and acting as a buffer to slow rice. winds across wetlands. The Minnesota Board of Water and Soil Resources (BWSR) has received Outdoor Heritage Funds to support and protect our state grain. Working in cooperation with the DNR and soil and water conservation districts, BWSR will complete 46 easement projects on 29 lakes and rivers. Funding for wild rice protection began in 2012. This first phase of the project was awarded $1.89 million which yielded 18 completed projects extending permanent protection to almost 10 miles of wild rice shoreland. -

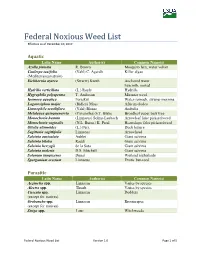

Federal Noxious Weed List Effective As of December 10, 2010

Federal Noxious Weed List Effective as of December 10, 2010 Aquatic Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Azolla pinnata R. Brown Mosquito fern, water velvet Caulerpa taxifolia (Vahl) C. Agardh Killer algae (Mediterranean strain) Eichhornia azurea (Swartz) Kunth Anchored water hyacinth, rooted Hydrilla verticillata (L.) Royle Hydrilla Hygrophila polysperma T. Anderson Miramar weed Ipomoea aquatica Forsskal Water-spinach, swamp morning Lagarosiphon major (Ridley) Moss African elodea Limnophila sessiliflora (Vahl) Blume Ambulia Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cavanilles) S.T. Blake Broadleaf paper bark tree Monochoria hastata (Linnaeus) Solms-Laubach Arrowleaf false pickerelweed Monochoria vaginalis (N.L. Burm.) K. Presl Heartshape false pickerelweed Ottelia alismoides (L.) Pers. Duck lettuce Sagittaria sagittifolia Linnaeus Arrowhead Salvinia auriculata Aublet Giant salvinia Salvinia biloba Raddi Giant salvinia Salvinia herzogii de la Sota Giant salvinia Salvinia molesta D.S. Mitchell Giant salvinia Solanum tampicense Dunal Wetland nightshade Sparganium erectum Linnaeus Exotic bur-reed Parasitic Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Aeginetia spp. Linnaeus Varies by species Alectra spp. Thunb. Varies by species Cuscuta spp. Linnaeus Dodders (except for natives) Orobanche spp. Linnaeus Broomrapes (except for natives) Striga spp. Lour. Witchweeds Federal Noxious Weed List Version 1.0 Page 1 of 5 Terrestrial Latin Name Author(s) Common Name(s) Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. ex Delile Prickly acacia = Vachellia nilotica (L.) P.J.H. Hurter & (updated 3/21/2017) Ageratina adenophora (Sprengel) King & Crofton weed Ageratina riparia (Regel) King & H. Rob. Mistflower, spreading snakeroot Alternanthera sessilis (L.) R. Brown ex de Sessile joyweed Arctotheca calendula (L.) Levyns Capeweed Asphodelus fistulosus Linnaeus Onionweed (corrected 3/21/2107) Avena sterilis Durieu Animated oat, wild oat Carthamus oxyacantha M. -

Global Invasive Potential of 10 Parasitic Witchweeds and Related Orobanchaceae

Global Invasive Potential of 10 Parasitic Witchweeds and Related Orobanchaceae Item Type Article Authors Mohamed, Kamal I.; Papes, Monica; Williams, Richard; Benz, Brett W.; Peterson, A. Townsend Citation Mohamed, K.I., Papes, M., Williams, R.A.J., Benz, B.W., Peterson, A.T. (2006) 'Global invasive potential of 10 parasitic witchweeds and related Orobanchaceae'. Ambio, 35(6), pp. 281-288. DOI: 10.1579/05-R-051R.1 DOI 10.1579/05-R-051R.1 Publisher Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Journal Ambio Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States Download date 30/09/2021 07:19:18 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/623714 Report Kamal I. Mohamed, Monica Papes, Richard Williams, Brett W. Benz and A. Townsend Peterson Global Invasive Potential of 10 Parasitic Witchweeds and Related Orobanchaceae S. gesnerioides (Willd.) Vatke occurs throughout Africa, The plant family Orobanchaceae includes many parasitic perhaps thanks to its ability to develop host-specific strains, weeds that are also impressive invaders and aggressive each with a narrow host range. Indeed, Mohamed et al. (2) crop pests with several specialized features (e.g. micro- described eight host-specific strains, the most economically scopic seeds, parasitic habits). Although they have important being those attacking cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) provoked several large-scale eradication and control efforts, no global evaluation of their invasive potential is Walp.) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Other strains are as yet available. We use tools from ecological niche reported on diverse wild dicot plants of no commercial value, modeling in combination with occurrence records from including a strain found in the southeastern United States. -

Drought-Tolerant Desmodium Species Effectively Suppress Parasitic Striga Weed and Improve Cereal Grain Yields in Western Kenya

Crop Protection 98 (2017) 94e101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Drought-tolerant Desmodium species effectively suppress parasitic striga weed and improve cereal grain yields in western Kenya * Charles A.O. Midega a, , Charles J. Wasonga a, Antony M. Hooper b, John A. Pickett b, Zeyaur R. Khan a a International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe), P.O. Box 30772, Nairobi 00100, Kenya b Biological Chemistry and Crop Protection Department, Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire AL5 2JQ, UK article info abstracts Article history: The parasitic weed Striga hermonthica Benth. (Orobanchaceae), commonly known as striga, is an Received 7 February 2017 increasingly important constraint to cereal production in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), often resulting in Received in revised form total yield losses in maize (Zea mays L.) and substantial losses in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). 14 March 2017 This is further aggravated by soil degradation and drought conditions that are gradually becoming Accepted 17 March 2017 widespread in SSA. Forage legumes in the genus Desmodium (Fabaceae), mainly D. uncinatum and Available online 24 March 2017 D. intortum, effectively control striga and improve crop productivity in SSA. However, negative effects of climate change such as drought stress is affecting the functioning of these systems. There is thus a need Keywords: Striga to identify and characterize new plants possessing the required ecological chemistry to protect crops Climate change against the biotic stress of striga under such environmental conditions. 17 accessions comprising 10 Desmodium species of Desmodium were screened for their drought stress tolerance and ability to suppress striga. -

Witch Weeds (Striga Species)

Invasive plant risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Witchweeds AeStriga spp. Steve Csurhes, Anna Markula and Yuchan Zhou First published 2013 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/ deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: An area of corn (maize) that has been severely stunted by Striga (in Africa) Photo: CIMMYT undated, International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center – used with permission under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license) Invasive plant risk assessment: Witchweeds Striga species 2 Contents Summary 4 Introduction 5 Identity and taxonomy 5 Description 6 Reproduction and dispersal 8 Origin and distribution 9 Preferred habitat 10 History as a weed elsewhere 11 Pest potential in Queensland 14 Current distribution and impact in Queensland and Australia 14 Potential impact in Queensland 15 Control 18 References 18 Invasive plant risk assessment: Witchweeds Striga species 3 Summary The genus Striga comprises at least 30 species (the exact number of species is unclear due to taxonomic uncertainty). Three species, Striga hermonthica, S. asiatica and S. gesnerioides, are among the world’s worst weeds.