Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Modern Languages Faculty publications Modern Languages 7-2016 Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction Arthur B. Evans DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/mlang_facpubs Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Arthur B. "Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction." Science Fiction Studies Vol. 43, no. 2, #129 (July 2016), pp. 194-206. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Modern Languages at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Languages Faculty publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 194 SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES, VOLUME 43 (2016) Arthur B. Evans Anachronism in Early French Futuristic Fiction Pawe³ Frelik, in his essay “The Future of the Past: Science Fiction, Retro, and Retrofuturism” (2013), defined the idea of retrofuturism as referring “to the text’s vision of the future, which comes across as anachronistic in relation to contemporary ways of imagining it” (208). Pawe³’s use of the word “anachronistic” in this definition set me to thinking. Aren’t all fictional portrayals of the future always and inevitably anachronistic in some way? Further, I saw in the phrase “contemporary ways of imagining” a delightful ambiguity between two different groups of readers: those of today who, viewing it in retrospect, see such a speculative text as an artifact, an inaccurate vision of the future from the past, but also the original readers, contemporary to the text when it was written, who no doubt saw it as a potentially real future that was chock-full of anachronisms in relation to their own time—but that one day might no longer be. -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker. -

The Future Past: Intertextuality in Contemporary Dystopian Video Games

The Future Past: Intertextuality in Contemporary Dystopian Video Games By Matthew Warren CUNY Baccalaureate for Unique and Interdisciplinary Studies Submitted to: Timothy Portlock, Advisor Hunter College Lee Quinby, Director Macaulay Honors College Thesis Colloquium 9 May 2012 Contents I. Introduction: Designing Digital Spaces II. Theoretical Framework a. Intertextuality in the visual design of video games and other media b. Examining the established visual iconography of dystopian setting II. Textual Evidence a. Retrofuturism and the Decay of Civilization in Bioshock and Fallout b. Innocence, Iteration, and Nostalgia in Team Fortress and Limbo III. Conclusion 2 “Games help those in a polarized world take a position and play out the consequences.” The Twelve Propositions from a Critical Play Perspective Mary Flanagan, 2009 3 Designing Digital Spaces In everyday life, physical space serves a primary role in orientation — it is a “container or framework where things exist” (Mark 1991) and as a concept, it can be viewed through the lense of a multitude of disciplines that often overlap, including physics, architecture, geography, and theatre. We see the function of space in visual media — in film, where the concept of physical setting can be highly choreographed and largely an unchanging variable that comprises a final static shot, and in video games, where space can be implemented in a far more complex, less linear manner that underlines participation and system-level response. The artistry behind the fields of production design and visual design, in film and in video games respectively, are exemplified in works that engage the viewer or player in a profound or novel manner. -

Wasn't the Future Wonderful?

Wasn’t the Future Wonderful? UG7_Pascal Bronner & Thomas Hillier_ 2017/18 Image: Cathedral City, 1988. Iskander Galimov Image: Cathedral City, “No sensible decision can be made any longer without taking into account not only the world as it is, but the world as it will be.” - Isaac Asimov - If Wikipedia is to be believed, in 1967, author T.R Hinchcliffe wrote the Pelican book Retro-Futurism with the intention of examining major recurrent themes in mans’ many analogue predictions and prophecies of the future, from inspired fantasy to factually based notions, their cultural & scientific impact, the brilliance (or otherwise) of those ideas, and how they are now faring at the apparent dawning of the, then electronic future. Although a recent neologism, Retrofuturism continues to portray the future, combining recent ideas of nostalgia and retro with the traditions of futurism to explore the tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. This occurs when pre-1960’s futuristic visions by writers, artists and filmmakers are re-examined, refurbished and updated for the present day, offering a nostalgic, counterfactual image of what the future might have been, allowing us to rebuild the imagination and dreams of the past. As we travel deeper into the digital age, are we loosing the ability to look at the future in this romantic way? Past visions of the future were teeming with distinct qualities and weird and wonderful worlds, worlds so far removed from the spirit of today. From Jules Verne’s Novels to Jean Marc Cote’s illustrations, these worlds were intrinsically linked with the technology they portrayed. -

SCIENCE FICTION CINEMA Spring 2016

SCIENCE FICTION CINEMA Spring 2016 "Learn from me . how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow." Victor Frankenstein Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus (1818) Course Description and Objectives Communication 323, Science Fiction Cinema, will primarily focus on the examination of the North American science fiction film genre. The readings, lectures, and screenings are organized historically to facilitate an understanding of the evolution of science fiction cinema within a cultural context. The course is also designed to expand the student's understanding of the critical/cultural theoretical approaches most commonly employed in the analysis of science fiction texts. The format for each class will consist of lecture, screening, and discussion. Assigned readings and screenings must be completed on time to facilitate the class discussions. Students are expected to watch at least one assigned film outside of class each week. Informed class participation is an important part of this class Faculty Jeff Harder Office: Lewis Tower 908 Phone: 312-915-6896 e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Monday 3-4 and 7-8, Tuesday 5-6:30, Wednesday 1-3, and by appointment. Required Texts Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (available online at gutenberg.org) Liquid Metal: The Science Fiction Film Reader edited by Sean Redmond (online) Science Fiction Film by J.P. Telotte Reserve Readings and EBL/Full Text A Distant Technology: Science Fiction Film and the Machine Age by J.P. Telotte Alien Zone II edited by A. -

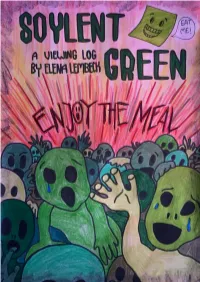

Soylentgreen.Pdf

1 von 14 Pre-Viewing How often do I watch films? I usually watch at least one film every weekend, mostly together with my family. The advantage of weekend-watching is that I can afford staying up late without getting in trouble. From Monday to Friday (if I watch anything at all), I tend to only watch one episode of a series a day, because this does not take as much time as watching a whole film. During the exam period I watch less movies, even on the weekends, whereas in the holidays it could happen that I nearly watch one movie per day. In general, I prefer movies (or at least short series) to longer series, because sadly I often watch one season, then lack the time to continue, and in the end I have lost interest in the story or the characters – so I don’t finish the series at all. Therefore, a longer series has to be of a high quality in terms of plot and characters (for example “Downton Abbey“), otherwise it doesn’t really make sense to me to watch the series until the end. What are my sources? I’m a stereo-typical DVD-person, increasingly changing to the use of Blue-Rays. My parents didn’t want me to watch TV when I was young, therefore I never got used to watching it and these days don’t feel the need to. I also use the streaming platform Netflix and sometimes the Amazon Prime of my brother, who doesn’t have to pay for it because he’s an undergraduate. -

New Practices, New Pedagogies

INNOVATIONS IN ART AND DESIGN NEW PRACTICES NEW PEDAGOGIES a reader EDITED BY MALCOLM MILES SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Printed in Copyright © 2004 …… All rights reserved. No part of this publication of the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the authors for any damage to properly or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. www ISBN ISSN The European League of Institutes of the Arts - ELIA - is an independent organisation of approximately 350 major arts education and training institutions representing the subject disciplines of Architecture, Dance, Design, Media Arts, Fine Art, Music and Theatre from over 45 countries. ELIA represents deans, directors, administrators, artists, teachers and students in the arts in Europe. ELIA is very grateful for support from, among others, The European Community for the support in the budget line 'Support to organisations who promote European culture' and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Published by SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Supported by the European Commission, Socrates Thematic Network ‘Innovation in higher arts education -

The Functions of Apocalyptic Cinema in American Film

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 21 Article 36 Issue 1 April 2017 4-1-2017 Global Catastrophe in Motion Pictures as Meaning and Message: The uncF tions of Apocalyptic Cinema in American Film Wynn Gerald Hamonic Thompson Rivers University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Hamonic, Wynn Gerald (2017) "Global Catastrophe in Motion Pictures as Meaning and Message: The unctF ions of Apocalyptic Cinema in American Film," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 36. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol21/iss1/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global Catastrophe in Motion Pictures as Meaning and Message: The Functions of Apocalyptic Cinema in American Film Abstract The ts eady rise in production of American apocalyptic films and the genre's enduring popularity over the last seven decades can be explained by the functions the film genre serves. Through an analysis of a broad range of apocalyptic films along with the application of several theoretical and critical approaches to the study of film, the author describes seven functions commonly found in American apocalyptic cinema expressed both in terms of its meaning (the underlying purpose of the film) and its message (the ideas the filmmakers want to convey to the audience). Apocalyptic cinema helps the viewer make sense of the world, offers audiences strategies for managing crises, documents our hopes, fears, discourses, ideologies and socio-political conflicts, critiques the existing social order, warns people to change their ways in order to avert an imminent apocalypse, refutes or ridicules apocalyptic hysteria, and seeks to bring people to a religious renewal, spiritual awakening and salvation message. -

“Evolution Takes Love:” Tracing Some Themes of the Solarpunk Genre

“Evolution Takes Love:” Tracing Some Themes of the Solarpunk Genre By William Kees Schuller A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in English Language and Literature in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September, 2019 Copyright © William Kees Schuller, 2019 Schuller i Schuller Abstract This project aims at examining some of the core themes and concerns of Solarpunk, a newly emerging genre. Placing Solarpunk in contrast to one of its nearest literary predecessors, Cyberpunk, I work to unify the disparate definitions of the Solarpunk genre, while examining the ways in which it departs from its Cyberpunk roots while retaining a radical critical mode. By mapping and defining some of Solarpunk’s primary concerns in this way, this project aims to set the groundwork for additional critical work on the Solarpunk genre, providing a foundation from which other scholars may work. Throughout the thesis I work primarily with the four English language Solarpunk anthologies, Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World, Wings of Renewal: A Solarpunk Dragons Anthology, Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation, and Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers. In Chapter One, I examine the interrelationship of social ecology, technological progress, and social progress with questions of community and society, in order to demonstrate the ways in which Solarpunk promotes its ideal, social ecology inspired future. In Chapter Two, I build on the generic interest in progress in order to examine Solarpunk’s optimistic treatment of the posthuman in relation to questions of physiological and capitalist consumption, and fears over the loss of humanity. -

Understanding Steampunk As Triadic Movement

Creating the Future-Past: Understanding Steampunk as Triadic Movement Master's Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Cultural Production Program Mark Auslander, Program Chair, Advisor Ellen Schattschneider, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master's Degree by Kimberly Burk August 2010 Copyright by Kimberly Burk © 2010 Abstract Creating the Future-Past: Understanding Steampunk as Triadic Movement A thesis presented to the Cultural Production Department Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Kimberly Burk Steampunk is a cultural phenomenon which takes a different shape than many other subcultures and countercultures which have proceeded it. This new shape is a significant variation from the paradigm and can be interpreted as a model of socio- cultural progression. By blending opposites like future and past, humanism and technology, this subcultural phenomenon offers symbolic solution model by way of triadic movement and transcendent function. Steampunk seems to be created and defined from the bottom up in that it tries to collapse hierarchies, use creativity and innovative thinking to solve problems and to challenge limits, and uses anachronism, retrofuturism, speculative and alternate realms to inspire individuals and groups to re-imagine and redress the issues and paradigms which have limited them. Through research, interview, participant observation and analysis, this piece explores and explains how the productions -

A History of the Future: Notes for an Archive Author(S): Veronica Hollinger Source: Science Fiction Studies, Vol

SF-TH Inc A History of the Future: Notes for an Archive Author(s): Veronica Hollinger Source: Science Fiction Studies, Vol. 37, No. 1 (March 2010), pp. 23-33 Published by: SF-TH Inc Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40649583 . Accessed: 30/01/2014 13:05 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. SF-TH Inc is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Science Fiction Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 131.111.184.22 on Thu, 30 Jan 2014 13:05:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions A HISTORY OF THE FUTURE 23 VeronicaHollinger A Historyof the Future: Notesfor an Archive A Historyof SF's Futures Onceagain, now that we knowwe aredifferently futured, we canlearn from sf. - JohnClute, Lookat theEvidence (278) Fromthe expansive anxieties of H.G. Wells's late-nineteenth-centuryTheTime Machine (1895) to the expansiveoptimism of the early-twentieth-century Americanpulps; from post-World-War-II nuclear apocalypticism to cyberpunk's self-styledboredom with the apocalypse; fromthe wild swings between contemporarynear-future realism and far-future hard-sf space opera to the crisis ofrepresentation ofthe Vingean Singularity - one historyof sciencefiction that I'd like to read is a historyof sciencefiction's futures, especially its literary futures.In lieuof putting it together myself, what I'll do todayis outline,in very broadstrokes, some of the things I'd liketo see in thiskind of project. -

Best Movies in Every Genre

Best Movies in Every Genre WTOP Film Critic Jason Fraley Action 25. The Fast and the Furious (2001) - Rob Cohen 24. Drive (2011) - Nichols Winding Refn 23. Predator (1987) - John McTiernan 22. First Blood (1982) - Ted Kotcheff 21. Armageddon (1998) - Michael Bay 20. The Avengers (2012) - Joss Whedon 19. Spider-Man (2002) – Sam Raimi 18. Batman (1989) - Tim Burton 17. Enter the Dragon (1973) - Robert Clouse 16. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) – Ang Lee 15. Inception (2010) - Christopher Nolan 14. Lethal Weapon (1987) – Richard Donner 13. Yojimbo (1961) - Akira Kurosawa 12. Superman (1978) - Richard Donner 11. Wonder Woman (2017) - Patty Jenkins 10. Black Panther (2018) - Ryan Coogler 9. Mad Max (1979-2014) - George Miller 8. Top Gun (1986) - Tony Scott 7. Mission: Impossible (1996) - Brian DePalma 6. The Bourne Trilogy (2002-2007) - Paul Greengrass 5. Goldfinger (1964) - Guy Hamilton 4. The Terminator (1984-1991) - James Cameron 3. The Dark Knight (2008) - Christopher Nolan 2. The Matrix (1999) - The Wachowskis 1. Die Hard (1988) - John McTiernan Adventure 25. The Goonies (1985) - Richard Donner 24. Gunga Din (1939) - George Stevens 23. Road to Morocco (1942) - David Butler 22. The Poseidon Adventure (1972) - Ronald Neame 21. Fitzcarraldo (1982) - Werner Herzog 20. Cast Away (2000) - Robert Zemeckis 19. Life of Pi (2012) - Ang Lee 18. The Revenant (2015) - Alejandro G. Inarritu 17. Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972) - Werner Herzog 16. Mutiny on the Bounty (1935) - Frank Lloyd 15. Pirates of the Caribbean (2003) - Gore Verbinski 14. The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) - Michael Curtiz 13. The African Queen (1951) - John Huston 12. To Have and Have Not (1944) - Howard Hawks 11.