The Functions of Apocalyptic Cinema in American Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NSF Current Newsletter Highlights Research and Education Efforts Supported by the National Science Foundation

March 2012 Each month, the NSF Current newsletter highlights research and education efforts supported by the National Science Foundation. If you would like to automatically receive notifications by e-mail or RSS when future editions of NSF Current are available, please use the links below: Subscribe to NSF Current by e-mail | What is RSS? | Print this page | Return to NSF Current Archive Robotic Surgery Systems Shipped to Medical Research Centers A set of seven identical advanced robotic-surgery systems produced with NSF support were shipped last month to major U.S. medical research laboratories, creating a network of systems using a common platform. The network is designed to make it easy for researchers to share software, replicate experiments and collaborate in other ways. Robotic surgery has the potential to enable new surgical procedures that are less invasive than existing techniques. The developers of the Raven II system made the decision to share it as the best way to move the field forward--though it meant giving competing laboratories tools that had taken them years to develop. "We decided to follow an open-source model, because if all of these labs have a common research platform for doing robotic surgery, the whole field will be able to advance more quickly," said Jacob Rosen, Students with components associate professor of computer engineering at the University of of the Raven II surgical California-Santa Cruz. Rosen and Blake Hannaford, director of the robotics systems. Credit: University of Washington Biorobotics Laboratory, led the team that Carolyn Lagattuta built the Raven system, initially with a U.S. -

Natural & Unnatural Disasters

Lesson 20: Disasters February 22, 2006 ENVIR 202: Lesson No. 20 Natural & Unnatural Disasters February 22, 2006 Gail Sandlin University of Washington Program on the Environment ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 1 Natural Disaster A natural disaster is the consequence or effect of a natural phenomenon becoming enmeshed with human activities. “Disasters occur when hazards meet vulnerability” So is it Mother Nature or Human Nature? ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 2 Natural Phenomena Tornadoes Drought Floods Hurricanes Tsunami Wild Fires Volcanoes Landslides Avalanche Earthquakes ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 3 ENVIR 202: Population & Health 1 Lesson 20: Disasters February 22, 2006 Naturals Hazards Why do Populations Live near Natural Hazards? High voluntary individual risk Low involuntary societal risk Element of probability Benefits outweigh risk Economical Social & cultural Few alternatives Concept of resilience; operationalized through policies or systems ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 4 Tornado Alley http://www.spc.noaa.gov/climo/torn/2005deadlytorn.html ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 5 Oklahoma City, May 1999 319 mph (near F6) 44 died, 795 injured 3,000 homes and 150 businesses destroyed ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 6 ENVIR 202: Population & Health 2 Lesson 20: Disasters February 22, 2006 World’s Deadliest Tornado April 26, 1989 1300 died 12,000 injured 80,000 homeless Two towns leveled Where? ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 7 Bangladesh ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 8 Hurricanes, Typhoons & Cyclones winds over 74 mph regional location 500,000 Bhola cyclone, 1970, Bangladesh 229,000 Typhoon Nina, 1975, China 138,000 Bangladesh cyclone, 1991 ENVIR 202: Lesson 20 9 ENVIR 202: Population & Health 3 Lesson 20: Disasters February 22, 2006 U.S. -

Is War Still Becoming Obsolete?

IS WAR STILL BECOMING OBSOLETE? John Mueller Department of Political Science University of Rochester reformatted August 3, 2012 Prepared for presentation at the 1991 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, The Washington Hilton, Washington, DC, August 29 through September 1, 1991. Copyright by the American Political Science Association. ABSTRACT: In Retreat from Doomsday: The Obsolescence of Major War I concluded, as the subtitle suggests, that "major war" (defined as "war among developed countries") is obsolescent (defined as becoming [not being] obsolete). Although war obviously persists in the world, an important and consequential change has taken place with respect to attitudes toward the institution of war, one rather akin to the processes by which the once-accepted institutions of slavery and dueling became extinct. This paper develops eleven topics that relate to the theme of the book: 1. Summarizes the obsolescence of major war argument. 2. Deals with the argument that nuclear weapons have largely been irrelevant to the remarkable absence of war in the developed world since 1945. 3. Speculates about the future of war in the post Cold War era. 4. Discusses the connection, if any, between war-aversion and pacificism. 5. Deals with the continuing fascination with war in a era free from major war and also with the notion that war is somehow the natural fate of the human race. 6. Expands the book's suggestion that Hitler was a necessary condition for world war in Europe. 7. Considers what the demise of the Cold War suggests about the concept of polarity and about the tenets of some forms of realism. -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

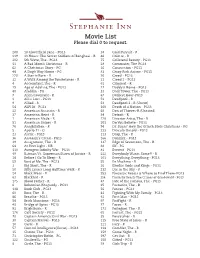

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

Why Call Them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960S Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK

Why Call them "Cult Movies"? American Independent Filmmaking and the Counterculture in the 1960s Mark Shiel, University of Leicester, UK Preface In response to the recent increased prominence of studies of "cult movies" in academic circles, this essay aims to question the critical usefulness of that term, indeed the very notion of "cult" as a way of talking about cultural practice in general. My intention is to inject a note of caution into that current discourse in Film Studies which valorizes and celebrates "cult movies" in particular, and "cult" in general, by arguing that "cult" is a negative symptom of, rather than a positive response to, the social, cultural, and cinematic conditions in which we live today. The essay consists of two parts: firstly, a general critique of recent "cult movies" criticism; and, secondly, a specific critique of the term "cult movies" as it is sometimes applied to 1960s American independent biker movies -- particularly films by Roger Corman such as The Wild Angels (1966) and The Trip (1967), by Richard Rush such as Hell's Angels on Wheels (1967), The Savage Seven, and Psych-Out (both 1968), and, most famously, Easy Rider (1969) directed by Dennis Hopper. Of course, no-one would want to suggest that it is not acceptable to be a "fan" of movies which have attracted the label "cult". But this essay begins from a position which assumes that the business of Film Studies should be to view films of all types as profoundly and positively "political", in the sense in which Fredric Jameson uses that adjective in his argument that all culture and every cultural object is most fruitfully and meaningfully understood as an articulation of the "political unconscious" of the social and historical context in which it originates, an understanding achieved through "the unmasking of cultural artifacts as socially symbolic acts" (Jameson, 1989: 20). -

Niels De Jong

r atin • • 1r1 lit nowledge and Empowerment on the David Icke Discussion Forum Niels de Jong Master thesis for the research master Religion & Culture 1 February 2013 First Advisor: Kocku.von Stuckrad (University of Groningen) Second Advisor: Stef Aupers (Erasmus University Rotterdam) NIELS DE JONG Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Research questions ................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Sociology of knowledge ...................................................................................................... 10 1.3 Preliminary definitions ........................................................................................................ 11 1.4 Davidicke.com/forum .......................................................................................................... 15 1.5 Method ................................................................................................................................ 16 1.5.1 Lurking ......................................................................................................................... 17 1.5.2 Ethics ........................................................................................................................... -

The End Is Now: Augustine on History and Eschatology

Page 1 of 7 Original Research The end is now: Augustine on History and Eschatology Author: This article dealt with the church father Augustine’s view on history and eschatology. After Johannes van Oort1,2 analysing the relevant material (especially his City of God and the correspondence with a certain Hesyschius) it was concluded that, firstly, Augustine was no historian in the usual sense of the Affiliations: 1Radboud University word; secondly, his concept of historia sacra was the heuristic foundation for his idea of history; Nijmegen, The Netherlands thirdly, the present is not to be described in the terms of historia sacra, which implies that he took great care when pointing out any instances of ‘God’s hand in history’; fourthly, the end 2Faculty of Theology, times have already started, with the advent of Jesus Christ; fifthly, because of the uniqueness University of Pretoria, South Africa of Christ’s coming, it runs counter to any cyclical worldview; sixthly, identifying any exact moment of the end of times is humanly impossible and seventhly, there is no room for any Note: ‘chiliastic’ expectation. Prof. Dr Johannes van Oort is Professor Extraordinarius in the Department of Church History and Church Polity of Preamble the Faculty of Theology at the University of Pretoria, Why should the church father Augustine figure in aFestschrift for an Old Testament scholar? I am South Africa. sure Prof. Pieter M. Venter will be aware of the answer, because both in his scientific research and in his outlook as a Reformed theologian, he knows about the church father’s main concerns. -

Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans

1 “Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans Ralph J. Poole “It’s Greek to whom?” In 2007-2008, a significant accumulation of cinematic and other visual media took up a celebrated episode of Greek antiquity recounting in different genres and styles the rise of the Spartans against the Persians. Amongst them are the documentary The Last Stand of the 300 (2007, David Padrusch), the film 300 (2007, Zack Snyder), the video game 300: March to Glory (2007, Collision Studios), the short film United 300 (2007, Andy Signore), and the comedy Meet the Spartans (2008, Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer). Why is the legend of the 300 Spartans so attractive for contemporary American cinema? A possible, if surprising account for the interest in this ancient theme stems from an economic perspective. Written at the dawn of the worldwide financial crisis, the fight of the 300 Spartans has served as point of reference for the serious loss of confidence in the banking system, but also in national politics in general. William Streeter of the ABA Banking Journal succinctly wonders about what robs bankers’ precious resting hours: What a fragile thing confidence is. Events of the past six months have seen it coalesce and evaporate several times. […] This is what keeps central bankers awake at night. But then that is their primary reason for being, because the workings of economies and, indeed, governments, hinge upon trust and confidence. […] With any group, whether it be 300 Spartans holding off a million Persians at Thermopylae or a group of central bankers trying to keep a global financial community from bolting, trust is a matter of individual decisions. -

Book of Eliʼ Weʼre Going to See Some Street-Oriented fighting

January 15, 2 010 Denzel Washington Directed by Albert Hughes (as The Hughes Brothers) Allen Hughes (as The Hughes Brothers) http://thebookofeli.warnerbros.com In the not-too-distant future, some 30 years after the final war, a solitary man walks across the wasteland that was once America. Empty cities, broken highways, seared earth—all around him, the marks of catastrophic destruction. There is no civilization here, no law. The roads belong to gangs that would murder a man for his shoes, an ounce of water…or for nothing at all. But theyʼre no match for this traveler. A warrior not by choice but necessity, Eli (Denzel Washington) seeks only peace but, if challenged, will cut his attackers down before they realize their fatal mistake. Itʼs not his life he guards so fiercely but his hope for the future; a hope he has carried and protected for 30 years and is determined to realize. Driven by this commitment and guided by his belief in something greater than himself, Eli does what he must to survive—and continue. Only one other man in this ruined world understands the power Eli holds, and is determined to make it his own: Carnegie (Gary Oldman), the self-appointed despot of a makeshift town of thieves and gunmen. Meanwhile, Carnegieʼs adopted daughter Solara (Mila Kunis) is fascinated by Eli for another reason: the glimpse he offers of what may exist beyond her stepfatherʼs domain. But neither will find it easy to deter him. Nothing—and no one—can stand in his way. Directed by: Albert Hughes, Eli must keepLorem moving Ipsum et: to fulfill his destiny and bring help to a ravaged humanity. -

Leonard, Philip. "Global Catastrophe." Orbital Poetics: Literature, Theory, World

Leonard, Philip. "Global Catastrophe." Orbital Poetics: Literature, Theory, World. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 107–140. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350075115.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 23:01 UTC. Copyright © Philip Leonard 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Global Catastrophe The end of the world, Shakespeare’s Lear tells us, will come when a vengeful nature overwhelms all that is known: Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage, blow! You cataracts and hurricanoes, spout Till you have drench’d our steeples, drowned the cocks! You sulphurous and thought-executing fires, Vaunt-couriers to oak-cleaving thunderbolts, Singe my white head! And thou, all-shaking thunder, Strike flat the thick rotundity o’ the world, Crack Nature’s moulds, all germens spill at once That make ingrateful man! (3.2.1–9) At this moment in the play, Lear has descended into madness following the catastrophic collapse of both family and kingdom. The bonds of blood and the principle of sovereign authority have been betrayed, and as a result civilization as he understands it has fallen into disarray. ‘Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks’ is his desperate apostrophe to an enraged nature that is unmoved by the plight of a humanity that struggles with its place in the world, and Lear addresses the unruly storm that engulfs him not to seek deliverance or absolution, but to yield to a greater authority. -

Conventions of the Play

Conventions of the Play Nikpreet Singh (SVV@G_D@VVG) Colin Ludwig Mu’az Abdul-aziz Julian Stanley IB English 12 Formal Structure Prologos ● Entire part of an ancient Greek play that precedes the parodos (an ode sung by the chorus at the entrance). Formal Structure Episodes ● One series of events throughout the course of the drama. Formal Structure Exodus ● Final scene or departure How do you think the final messenger influenced the exodus? DQ 1 Discussion: 1) Who? 2) Purpose? 3) Impact? “You are right; there is sometimes danger in too much silence” (1324). Use of Peripeteia and Anagnorisis Peripeteia = turning point or shift in the drama Page 2088 when the chorus begins speaking Anagnorisis = “recognition” When a character makes a crucial finding ● Find an example on page 2083 Conventions of a play Use of Chorus- Acts as a narrator for the play, giving info not given from the actors themselves How does Sophocles use the chorus as a proactive character and how would the story change if he used a different form of narration? DQ 2 ● Uses the chorus to ask question to Creon and find out what he’s thinking ● Chorus is the one who tells the messenger to go look for Conventions of a play Conventional Characters- Stereotypical characters that are usually flat Messengers used to deliver off stage to the audience Blind Seer- embodies a contradiction High Status Characters High on the social ladder, placed in a position of power In Antigone, status contributes to the pride of Creon and how he handles Antigone’s ‘crime’ Conventions of the Tragic Hero Aristotle’s Poetica: •This text is Aristotle’s theory on drama, and the general effects of drama on humanity.