The Establishment of Public Housing in Halifax, 1930-1953

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Lives in Downtown Halifax?

Jill L Grant and Will Gregory Dalhousie University Who Lives Downtown? Tracking population change in a mid-sized city: Halifax, 1951-2011 Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada How did planning policies in the post-war period affect the character and composition of the central city? Followed four central census tracts from 1951 to 2011 to look at how population changed Map by Uytae Lee based on HRM data Planning Changes 1945 Master Plan and 1950 Official Plan advocated slum clearance Urban renewal: Cleared the north central downtown http://spacing.ca/atlantic/2009/12/03/from-the-vaults-scotia-square/ http://www.halifaxtransit.ca/streetcars/birney.php Urban Design and Regional Planning Policy shifted: 1970s Downtown Committee and waterfront revitalization sought residents for downtown; heritage conservation. 1970s Metropolitan Area Planning Commission: regional planning forecast population explosion. Suburban expansion followed. https://www.flickr.com/photos/beesquare/985096478 http://www.vicsuites.com/ Amalgamation and the Regional Centre 1996: amalgamation created Halifax Regional Municipality. Smart city, smart growth vision Regional Centre: target to take 25% of regional growth until 2031. Central urban design plan, density bonusing: promoting housing. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halifax_Town_Clock Planning and Residential Development High density but primarily residential uses concentrated in south and north of downtown In Central Business District, residential uses are allowed on upper floors: residential towers. Since 2009, -

MEDIA RELEASE for Immediate Release Downtowns Atlantic

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release Downtowns Atlantic Canada Conference Brings Business Improvement Districts to Halifax May 23, 2018, Halifax, NS – Downtowns Atlantic Canada (DAC) is hosting its annual conference in Halifax, May 27‐29, 2018, attracting business improvement districts (BIDs), urban planners, small businesses, and municipal staff from the Atlantic provinces. Inspired by the challenges small businesses face on a day‐to‐day basis, this year's DAC Conference, "Bringing Small Business Matters to the Forefront," sets out to present a program dedicated to addressing small business issues. The keynote speakers and panel discussions will address many of these issues and provide BIDs the tools and motivation to lead small business communities and keep main streets vibrant and prosperous. “The DAC Conference is an excellent opportunity for delegates to share ideas and best practices,” said Paul MacKinnon, DAC President and Executive Director of Downtown Halifax Business Commission. “This year’s focus is an important one as we need to support the needs of small businesses to maintain healthy and thriving downtowns and main streets.” The 2018 DAC Conference is co‐hosted by the eight business improvement districts in Halifax: Downtown Dartmouth Business Commission, Downtown Halifax Business Commission, North End Business Association, Sackville Business Association, Spring Garden Area Business Association, Spryfield Business Commission, Quinpool Road Mainstreet District Association, and Village on Main – Community Improvement District. To stay up‐to‐date and to join the conversation, follow #DACHalifax2018 on Twitter and Instagram. There are two sessions at the DAC Conference that are free and open to the public: DAC Opening Night PechaKucha 7:30 to 10:00 pm – Sunday, May 27 The Seahorse Tavern PechaKucha 20x20 is a simple presentation format where presenters show 20 images, each for 20 seconds. -

TABLE of CONTENTS 1.0 Background

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Background ....................................................................... 1 1.1 The Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The Study Process .............................................................................................. 2 1.2 Background ......................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Early Settlement ................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Community Involvement and Associations ...................................................... 4 1.5 Area Demographics ............................................................................................ 6 Population ................................................................................................................................... 6 Cohort Model .............................................................................................................................. 6 Population by Generation ........................................................................................................... 7 Income Characteristics ................................................................................................................ 7 Family Size and Structure ........................................................................................................... 8 Household Characteristics by Condition and Period of -

Halifax Transit Riders' Guide

RIDERS’ GUIDE Effective November 23, 2020 311 | www.halifax.ca/311 Departures Line: 902-480-8000 halifax.ca/transit @hfxtransit TRANSIT Routes The transit fleet is 100% accessible and equipped with bike racks. 1 Spring Garden 5 2 Fairview page 7 3 Crosstown 11 4 Universities 15 5 Chebucto 19 7 Robie 20 8 Sackville 22 9A/B Herring Cove 28 10 Dalhousie 34 11 Dockyard 37 14 Leiblin Park 38 21 Timberlea 40 22 Armdale 42 25 Governors Brook 44 28 Bayers Lake 45 29 Barrington 46 30A Parkland 48 30B Dunbrack 48 32 Cowie Hill Express 50 39 Flamingo 51 41 Dartmouth—Dalhousie 52 51 Windmill 53 53 Notting Park 54 54 Montebello 55 55 Port Wallace 56 56 Dartmouth Crossing 57 57 Russell Lake 58 58 Woodlawn 59 59 Colby 60 60 Eastern Passage—Heritage Hills 62 61 Auburn—North Preston 66 62 Wildwood 70 63 Woodside 72 64 Burnside 73 65 Caldwell (stop location revised) 74 66 Penhorn 75 68 Cherry Brook 76 72 Portland Hills 78 78 Mount Edward Express 79 79 Cole Harbour Express 79 82/182 First Lake/First Lake Express 80 83/183 Springfield/Springfield Express 82 84 Glendale 84 85/185 Millwood/Millwood Express 85 86/186 Beaver Bank/Beaver Bank Express 88 87 Sackville—Dartmouth 90 88 Bedford Commons 92 90 Larry Uteck 93 91 Hemlock Ravine 97 93 Bedford Highway 99 123 Timberlea Express 99 135 Flamingo Express 100 136 Farnham Gate Express 100 137 Clayton Park Express 101 138 Parkland Express 101 159 Portland Hills Link 102 182 First Lake Express 103 183/185/186 Sackville Express Routes 104 194 West Bedford Express 105 196 Basinview Express 106 320 Airport—Fall River Regional Express 107 330 Tantallon—Sheldrake Lake Regional Express 108 370 Porters Lake Regional Express 108 401 Preston—Porters Lake—Grand Desert 109 415 Purcells Cove 110 433 Tantallon 110 Ferry Alderney Ferry and Woodside Ferry 111 Understanding the Route Schedules This Riders' Guide contains timetables for all Halifax Transit routes in numerical order. -

Downtown Halifax (2 to 4 Hrs; ~ 11 Km Or 7 Miles)

Downtown Halifax (2 to 4 Hrs; ~ 11 km or 7 miles) This route can be completed in as little as two hours however we recommend planning for a commitment of four giving you time to experience each of the destinations and stop for lunch. This self-guided route allows you to stop n’ go as you like while you explore Downtown Halifax’s primary sights & attractions. FAQ: Did you know that people living in Halifax are known as “Haligonians”? Highlights: Halifax Waterfront, Farmer’s Market, Point Pleasant Park, Public Gardens, Spring Garden Road, Citadel Hill, Halifax Central Library, City Hall, Argyle Street, and Pizza Corner. Key Neighbourhoods: Downtown, Waterfront, South End Tips // Things to do: • Try a donair, poutine or lobster roll at Pizza Corner • Grab a soft serve ice cream at the Dairy Bar • Get your photo with the Drunken Lamp Posts • Retrace Halifax’s role as a military bastion as you explore fortress relics in Point Pleasant Park later making your way in the center of it all, Citadel Hill • Catch incredible views atop the award winning Halifax Central Library • Take your pick for a patio on Argyle Street • Get a selfie at the internationally recognized Botkin Mural outside Freak Lunch (if you haven’t had ice cream yet, Freak Lunch Box has amazing milkshakes.) Lost? Give us a call we will put you back on track 902 406 7774 www.iheartbikeshfx.com Line Busy? Call our Support Line at 902 719 4325. 1507 Lower Water Street Notes // Safety Tips: - On road riding is required for this route. -

Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax

ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX Atlantic Maritimes Explorer by Rail | Montreal to Halifax Eastern Canada Rail Vacation 8 Days / 7 Nights Montreal to Halifax Priced at USD $2,853 per person Prices are per person and include all taxes. Child age 10 yrs & under INTRODUCTION Experience the best of Montreal, Quebec City, Prince Edward Island in just over a week on this Atlantic Maritimes Explorer Train Trip. Discover Canada as you've never seen it before on a trip with VIA Rail through the Atlantic and Maritime provinces. Witness the dynamic landscapes change from cosmopolitan cities to quirky towns and enjoy your choice of tours in Montreal and Charlottetown. From wandering the local food market on foot to cruising for lobster by boat, each moment is as adventurous as the next. Itinerary at a Glance DAY 1 Arrive Montreal DAY 2 Montreal | Day Tour to Quebec City & Montmorency Falls DAY 3 Montreal | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 3 Excursions Montreal to Charlottetown| VIA Rail Option 1. Montreal Half Day Sightseeing Tour Option 2 Walking Tour of Old Montreal Option 3 Beyond the Market Food Walking Tour DAY 4 Arrive Charlottetown | VIA Rail + Private Transfer DAY 5 Charlottetown | Island Drives & Anne of Green Gables Tour DAY 6 Charlottetown | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 2 Excursions Option 1. Morning Lobster Cruise Option 2. Morning Charlottetown Highlights Tour Charlottetown to Halifax| Private Transfer Start planning your vacation in Canada by contacting our Canada specialists Call 1 800 217 0973 Monday - Friday 8am - 5pm Saturday 8.30am - 4pm Sunday 9am - 5:30pm (Pacific Standard Time) Email [email protected] Web canadabydesign.com Suite 1200, 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1N2, Canada 2021/06/14 Page 1 of 6 ATLANTIC MARITIMES EXPLORER BY RAIL | MONTREAL TO HALIFAX DAY 7 Halifax | Freedom of Choice - Choose 1 of 4 Excursions Option 1. -

Halifax Sport Heritage Walking Tour

Halifax Sport Heritage Walking Tour Self-Guided The Downtown Core Loop ◆ Walking time (non-stop): 50 minutes ◆ Recommended time: 2 hours◆ Difficulty: Easy-Medium The Nova Scotia Sport Hall of Fame was established by John “Gee” Ahern, Mayor of Halifax in the 1940s, as a response to Kingston, Ontario’s claimof being the birthplace of hockey. The Hall of Fame officially opened on November 3rd, 1964 and moved locations many times over the decades as it continued to grow. It moved to its current location adjacent to the Scotiabank Centre in 2006. Make sure you check out Sidney Crosby’s famous dryer and try your skills in the multi-sport simulator! Ahern Avenue is located between Citadel High School and Citadel Hill and was named after John “Gee” Ahern (below). Ahern was the mayor of Halifax from 1946 to 1949 and was also a member of the Nova Scotia Legislature. Ahern felt strongly that there should be recognition for Nova Scotia athletes. He initiated the formation of the Hall of Fame in 1958 and was later inducted in 1982 for his contributions to hockey, baseball and rugby in Nova Scotia. The Halifax Public Gardens opened in the The Wanderers Grounds were established 1840s and became the home of Canada’s in the 1880s and were once a part of the first covered skating rink in 1863, followed Halifax Commons. These grounds were by the first public lawn tennis court in the home to the Wanderers Amateur Athletic country in 1876. The gardens’ pond was a Club for rugby, lawn bowling and more. -

Proposed 2019/20 Multi-Year Halifax Transit Budget and Business Plan

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 4 Budget Committee January 30, 2019 TO: Chair and Members of Budget Committee (Standing Committee of the Whole on Budget) SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: January 21, 2019 SUBJECT: Proposed 2019/20 Multi-year Halifax Transit Budget and Business Plan ORIGIN As per Administrative Order 1 and the Budget and Business Plan consultation schedule presented to Regional Council on October 16, 2018, staff is required to present the draft 2019/20 Business Unit Budget and Business Plans to the Budget Committee for review and discussion prior to consideration by Regional Council. At the May 22, 2012 meeting of Regional Council, the following motion was put and passed: Request that Metro Transit come to Regional Council one month prior to budget presentations to present any proposed changes to Metro Transit service so that Council has ample time to debate the proposed changes before the budget comes to Council. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Charter, section 35 (1) The Chief Administrative Officer shall (b) ensure that an annual budget is prepared and submitted to the Council. RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that the Budget Committee direct staff to prepare the Halifax Transit’s 2019/20 Multi- year Budget and Business Plan, as proposed in the accompanying presentation, based on the 1.9% option, and to prepare Over and Under items for that Plan as directed by Regional Council. BACKGROUND As part of the design of the 2019/20 Budget and Business Plan development process, the Budget Committee is reviewing each Business Unit’s budget and proposed plans, in advance of completing detailed HRM Budget and Business Plan preparation. -

Doers & Dreamers Travel Guide

Getting Around The travel times provided are approximate and have been calculated using Google Maps. Depending on the route between the destination points, Google considers both highway and secondary roads in the calculation. Please be aware that your travel time will be affected by other factors, such as side trips to attractions and activities in the region. 2020 DOERS & DREAMERS TRAVEL GUIDE Halifax International Maine to Amherst Digby Halifax North Sydney Pictou Yarmouth Airport Nova Scotia Advocate Harbour 2hr05 96km 5hr00 427km 3hr00 227km 5hr45 444km 2hr40 200km 6hr10 511km 2hr40 197km Amherst — — 4hr00 397km 2hr00 197km 4hr15 411km 2hr00 140km 5hr05 496km 1hr40 166km Annapolis Royal 3hr45 365km 0hr30 37km 2hr15 203km 6hr10 576km 3hr30 333km 1hr35 136km 2hr15 214km 2020 DOERS & DREAMERS TRAVEL GUIDE | 1-800-565-0000 2020 DOERS & DREAMERS TRAVEL Antigonish 2hr10 217km 4hr05 415km 2hr15 212km 2hr20 196km 0hr55 76km 5hr15 496km 1hr50 175km Aylesford 3hr00 300km 1hr10 100km 1hr30 130km 5hr25 510km 2hr40 268km 2hr10 198km 1hr25 141km Baddeck 3hr40 355km 5hr45 552km 3hr45 350km 0hr40 58km 2hr25 214km 6hr45 651km 3hr20 312km Bridgewater 3hr00 279km 2hr05 140km 1hr15 102km 5h20 489km 2hr45 247km 2hr20 204km 1hr20 115km Cape North 5hr45 490km 7hr45 688km 5hr45 485km 2hr20 140km 4hr25 349km 8hr45 768km 5hr20 447km Chéticamp 4hr40 400km 6hr35 595km 4hr40 395km 2hr00 145km 3hr20 257km 7hr50 678km 4hr25 364km Clark's Harbour 4hr45 437km 2hr10 180km 3hr10 262km 7hr15 649km 4hr35 405km 1hr05 81km 3hr25 280km Digby 4hr00 397km —— 2hr30 230km 6hr20 608km 3hr45 368km 1hr10 105km 2hr30 239km Guysborough 3hr00 279km 4hr55 477km 3hr00 274km 2hr30 199km 1hr40 138km 6hr05 557km 2hr45 235km Halifax 2hr00 197km 2hr30 230km —— 4hr20 408km 1hr45 165km 3hr20 304km 0hr31 39km Halifax Int. -

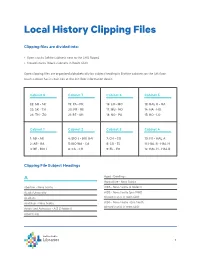

Local History Clipping Files

Local History Clipping Files Clipping files are divided into: • Open stacks (white cabinets next to the LHG Room) • Closed stacks (black cabinets in Room 440) Open clipping files are organized alphabetically by subject heading in 8 white cabinets on the 4th floor (each cabinet has its own key at the 4th floor information desk): Cabinet 8 Cabinet 7 Cabinet 6 Cabinet 5 22: SH - SK 19: PA - PR 16: LO - MO 13: HAL R - HA 23: SK - TH 20: PR - RE 17: MU - NO 14: HA - HO 24: TH - ZO 21: RE - SH 18: NO - PA 15: HO - LO Cabinet 1 Cabinet 2 Cabinet 3 Cabinet 4 1: AB - AR 4: BIO J - BIO U-V 7: CH - CO 10: FO - HAL A 2: AR - BA 5: BIO WA - CA 8: CO - EL 11: HAL B - HAL H 3: BE - BIO I 6: CA - CH 9: EL - FO 12: HAL H - HAL R Clipping File Subject Headings A Aged - Dwellings Agriculture - Nova Scotia Abortion - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia (2 folders) Acadia University AIDS - Nova Scotia (pre-1990) Acadians (closed stacks in room 440) Acid Rain - Nova Scotia AIDS - Nova Scotia - Eric Smith (closed stacks in room 440) Actors and Actresses - A-Z (3 folders) Advertising 1 Airlines Atlantic Institute of Education Airlines - Eastern Provincial Airways (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Atlantic School of Theology Airplane Industry Atlantic Winter Fair (closed stacks in room 440) Airplanes Automobile Industry and Trade - Bricklin Canada Ltd. Airports (closed stacks in room 440) (closed stacks in room 440) Algae (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Canadian Motor Ambulances Industries (closed stacks in room 440) Amusement Parks (closed stacks in room 440) Automobile Industry and Trade - Lada (closed stacks in room 440) Animals Automobile Industry and Trade - Nova Scotia Animals, Treatment of Automobile Industry and Trade - Volvo (Canada) Ltd. -

Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, Ns 1972 - 2016

MAPPING THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONDOMINIUMS IN HALIFAX, NS 1972 - 2016 by Colin K. Werle Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of GEOG 4526 for the Degree Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies Saint Mary’s University Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada © Colin Werle, 2017 April, 2017 Members of the Examining Committee: Dr. Mathew Novak (Supervisor) Assistant Professor, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Saint Mary’s University Dr. Ryan Gibson School of Environmental Design and Rural Development University of Guelph ABSTRACT Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle This thesis offers foundational insight into the spatial and temporal patterns of condominium development in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Characteristics that are analysed include: age, assessed values, building types, heights, number of units, and amenities. Results show that condominium development in Halifax first appeared in the suburbs in the 1970s, with recent activity occurring in more central areas. The greatest rate of development was experienced during a condominium boom in the late 1980s, however, development has been picking up over the last decade. Apartment style buildings are the major type of developments, with an average building size of 46.52 units. Similar to other markets in Canada, Halifax’s condominium growth does appear to be corresponding with patterns of re- centralization after decades of peripheral growth in the second half of the twentieth-century. April, 2017 ii RÉSUMÉ Mapping the Development of Condominiums in Halifax, NS from 1972 – 2016 by Colin K. Werle Cette dissertation donnera un aperçu des tendances spatiales et temporelles de base sur le développement des condominiums à Halifax (Nouvelle-Écosse). -

6140 Quinpool Road Halifax, Nova Scotia

FOR LEASE 6140 Quinpool Road Halifax, Nova Scotia Prime Quinpool Road Retail +/- 1,830 - 3,750 sf Lower-Level Retail Space | Lease Rate: $30.00 psf Gross PROPERTY OVERVIEW PROPERTY TYPE 2 storey commercial building, currently undergoing Easily accessible, Tenant parking substantial renovations. 20 + bus routes options available FEATURES Excellent opportunity to occupy 1,830 sf of space on the lower level of a retail building on a high traffic thoroughfare. This lower level space offers barrier free Over 30,000 cars High pedestrian access and a ceiling height of 10’ clear. A blank slate, passing daily traffic area tenants can customize the space based on their needs. AVAILABLE SPACE Approximately 1,830 sf with potential for up to 3,750 sf Building signage Barrier free access PANDEMIC-PREPARED with excellent with wheelchair roadside visibility elevator If a tenant is forced to close due to a pandemic (or state of emergency), they are not required to pay rent. Contact MEAGHAN MACDOUGALL Retail Sales & Leasing +1 902 266 6211 [email protected] FOR LEASE Aerial6140 / Location QuinpoolMap Road Halifax, Nova Scotia HALIFAX NORTH END HALIFAX COMMONS DOWNTOWN HALIFAX 6140 QUINPOOL ROAD QEII HEALTH SCIENCES CENTRE DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY ARMDALE ROTARY LOCATION Quinpool Road lies on the western edge of the Halifax Commons and serves as one of Halifax’s main arterial roads connecting the downtown core of Halifax with the Armdale Rotary, leading to the West End, Herring Cove, Armdale, Clayton Park, Fairview and Highway 102. You’ll be joining other prime retailers such as the NSLC, Wendy’s, TD Starbucks, Atlantic Superstore, Canadian Tire and many more.