Basic Ingredients of How to Improve Communications from School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clayborn Temple AME Church

«Sí- ’.I-.--”;; NEWS WHILE IT IS NEI FIRST IK YOUR ME WORLD ' i; VOLUME 23, NUMBER 100 MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE, TUESDAY, JUNE 14, 1955 « t With Interracial Committee (Special to Memphis World) NASHVILLE—(SNS) -N ashville and Davidson County school board officials moved to tackle the public school desegregation problem when last weekend both city and county school boards ordered studies begun on the school desegregation issue. t stand atom« dfee.Jwd The county board took the strong year. er action, directing the superinten The boards are said to be con dent and board chairman to work sidering three approaches to the out plans with an Interracial com school desegregation problem The mittee to be selected by the chair three approaches include (1) the man. "voluntary” approach wherein Ne The city board referred a copy gro parents would say whether of the Supreme Court ruling to one they want their children to register « IUaW of its standing committees along lit former "white" schools or re with a . request from Robert Remit main In Negro schools; (2) the FOUR-YEAR SCHOLARSHIP AWARDEES - Dr. and saluataforlan, respectively, of this year's ter, a white associate professor of abolition of all school zones which William L. Crump (left) Director of Tennessee Haynes High School graduating class. Both mathematics at Fisk, that his two would make it possible for students State University's Bureau,of Public Relations an’d young ladies were presented four-year academ children be admitted to "Negro" to register at the school of their schools. choice or i3> "gradual" integration Clinton Derricks (right) principal of the Haynes ic scholarships to Tennessee State during the A similar request by Mr. -

Racing/Cruising

II I ' jF x John P rker,Boats New & U ed Wayfarers in Stock Also all ou need to sail &Trail Wayfarert ecialist for over 15 years All popular Wayfarer S res, Combination Trailers Masts, Booms, Spinnaker Poles, Covers: Trailing, Over[ am and flat etc,etc. East Coast ager ts for Banks sails, proven to be undoubtedly the ultimate in choice for fast Wayfarer Salik Also Sail Repair Facilities Available. All these and much more, usually from stock Mail.Qrder and credit Card Facilities Availk arker Boats becki ea ... Winter 2003 Issue 100 Next Issue Contents Copy date for the Spring 2004 issue will be 5 February 2004 Commodore's Corner 5 Once upon a Time 7 Pamela Geddes Racing Secretary's Ruminations 9 Kirkbrae House, Langhouse Rd, Inverkip, Rule Changes 11 Greenock. PAI16 OBJ. AGM Notice 14 Executive Committee Nominations 17 Tel: 01475 521327 Scottish Championship 18 Email editor~wayfarer.org.uk Yearbook 20 Don' fogetwheour opy sedingin Racng Pogrmme21 to add who wrote it and the boat number, Woodies are back 24 please. Also for photos, so that credit can Woodies are back are they? 26 be given. Thanks. Parkstone .31 Lymington Town SC 33 New kid on the block 36 Beech Bough "37 Fairway Trophy 38 : Rules & Technical Information 42 Restoration Project 43 A Trip down Memory Creek 45 Every effort has been made to make Our trip - W Coast of Scotland 50 the information as aceurate as possible. Prov. Cruising Programme 56 Nevertheless, neither the UJKWA, nor itsCringSmar6 Committees or Editor will accept responsi- Ullswater 63 bility for any error, inaccuracy, omission Sailing the Heritage Coast 65 from or statement contained in it. -

Rigging Lark 2252

Rigging Lark 2252 Introduction This booklet was inspired by reading the Wayfarer guide to rigging and racing. The wayfarer guide includes a lot more information than just rigging and is worth a read even if you sail a different class. This guide describes how Lark 2252 is rigged and will hopefully help those new to Lark sailing that has an older boat. It is not the definitive way to rig and some things might change as I gain more experience sailing this exciting and rewarding class. If you have one of the Rondar Larks or are thinking about setting up the control lines and rigging from scratch then consult the rigging guide written by Simon Cox and available from the class website. Lark 2252 was built by Parkers in 1989. Although it is a MK2 much of the rigging is similar to the MK1s. I believe in keeping things as simple as possible and only having adjustable controls you actually adjust on the water. However, if you need to adjust controls they need to be easy to use and fall to hand. While the latest shiny gadgets and brand new sails may look nice, if your basic boat handling and tactics are poor you’ll still sail slowly whatever you spend. After all, what good are those £800 new sails if you’re always in someone’s dirty wind! Finally, join the class association, everyone is very friendly and helpful and you’ll be doing your bit to keep the class alive. Garry Packer 10th July 2004. Hull Make sure your hull is smooth; fill the worst imperfections with gel coat filler or epoxy and microballons and sand wet with 600 – 1200 paper. -

Buying a Lark Barker, Parker, Rondar, Ovington

Barker, Parker, Rondar, Ovington Buying a Lark Over the 40 years Larks have been in production over 2500 hulls have been made. Some of which are owned and raced regularly, however many are sitting in dinghy parks or garages providing a safe habitat for an abun- dance of wildlife. The materials used and build quality of the Lark means that virtually all of these hulls could be restored with minimum expense and therefore offer an excellent opportunity for sailors on a budget. This means you can buy a Lark second hand from as little as £50, they regularly come up on sites like E-bay, Apollo Duck and in Yachts and Yachting and Dinghy Sailing Magazine as well as on the lark web-site www.larkclass.org . So when shopping for a Lark what should you expect to get for your money: Booking Form Boat Numbers 1-1838 – Baker Lark Boat Numbers 1839-2454 Parker Lark Baker was the original Lark builder from 1967 right Parker took over building the Lark and built a huge num- up until the late 1970’s and built the vast majority of ber of Larks throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s, including Larks in terms of numbers. The boats are still fan- a huge number for Universities and Colleges who often tastic sailing and racing boats, but have suffered replaced theirP fleetsa six boats at a time. Parker Larks from issues with hull andk centreboarder case stiffness are still extremely competitiverke if they have been well as the have agedB (thea oldest are now over 40 years maintained and looked after, andr offer a cheap and old). -

Nicky Souter (Sailing Director)

Nicky Souter (Sailing Director) 5th year as RYC Sailing Director Hometown: Sydney, Australia Home Club: Prince Alfred YC Sailing Experience: Women’s Match Racing World Champion (2009), No. 1 ISAF ranking (2011), superyachts (Silencio, Tribe, Wild Oats) Fun fact: I took a boat to school every day when growing up. Key Becker (Head Instructor) Junior at the College of Charleston 10 years in Big Boats (offshore & inshore) consisting of many one-design boats, sport boats, and maxis / 8 years in Dinghies consisting of Optis, 420’s, Lasers, FJ’s, Moths, 29ers Special Talents: Known for climbing masts and making awesome nachos My favorite sailing memory was finding a whale carcass in the Pacific Ocean which led to catching lots of fish and making for 5 days of really good offshore meals. I am most looking forward to sharing the joy of sailing with campers and great days on the water. Emily Kuchta (aka Mum – Assistant to the Sailing Director) I received my Masters in Early Childhood Education at Manhattanville College and my BA in Elementary Education from New England College working at Sacred Heart in Greenwich as a Kindergarten teacher. I have not done any sailing but know a lot about the JSA website and booking/organizing regattas! Special Talents: I can do a handstand and play ice hockey! Ashton Borcherding Stanford University Class of 2022 I have sailed 2 years in Optis on LIS and 2 years in c420’s out of Belle Haven. I have 5 years in i420’s with LISOT. Special Talents: I speak French. My favorite sailing memory was competing in Auckland New Zealand in the i420. -

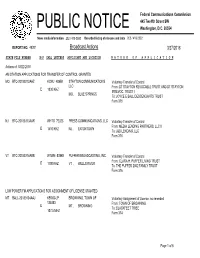

Broadcast Actions 3/27/2018

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49201 Broadcast Actions 3/27/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 03/22/2018 AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR TRANSFER OF CONTROL GRANTED MO BTC-20180212AAZ KCWJ 48959 STAYTON COMMUNICATIONS Voluntary Transfer of Control LLC From: DT STAYTON REVOCABLE TRUST AND DT STAYTON E 1030 KHZ IRREVOC. TRUST I MO , BLUE SPRINGS To: JOYCE E BALL DESCENDANTS TRUST Form 315 NJ BTC-20180313AAR WHTG 72323 PRESS COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Voluntary Transfer of Control From: MEDIA LENDING PARTNERS, LLC II E 1410 KHZ NJ ,EATONTOWN To: J&D LENDING, LLC Form 316 VT BTC-20180314ABB WTWN 53865 PUFFER BROADCASTING, INC. Voluntary Transfer of Control From: CLARA H. PUFFER LIVING TRUST E 1100 KHZ VT , WELLS RIVER To: THE PUFFER 2002 FAMILY TRUST Form 316 LOW POWER FM APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE GRANTED MT BALL-20180104AAJ KBWG-LP BROWNING, TOWN OF Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended 134853 From: TOWN OF BROWNING E MT ,BROWNING To: BLACKFEET TRIBE 107.5 MHZ Form 314 Page 1 of 6 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 49201 Broadcast Actions 3/27/2018 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N Actions of: 03/22/2018 LOW POWER FM APPLICATIONS FOR MINOR MODIFICATION TO A CONSTRUCTION PERMIT GRANTED FL BMPL-20180321AAR WXDN-LP AWAKENING/ART & CULTURE Low Power FM Mod of CP to chg 192636 E FL , ORLANDO 99.7 MHZ FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR LICENSE TO COVER GRANTED CA BLED-20180312ABS KGGN 184593 FIRST BAPTIST CHURCH OF License to cover. -

The 48Th 24 Hour Race Special

mastThe THE MAGAZINE FOR THE COMPETITIVE SAILOR THE 48TH 24 HOUR RACE SPONSORED BY SPECIAL THE CREWSAVER 24 HOUR DINGHY RACE WEST LANCASHIRE YACHT CLUB 13th & 14th September 2014 Ian Donaldson Commodore As Commodore of West Lancashire Yacht Club it is a great honour for me to welcome all competitors, sponsors, and many long standing friends and guests to our Club. We truly appreciate your continued support for the Crewsaver 24 Hour Race, an unrivalled event, now in its 48th year. HEN planning for the original race in 1967, although our the Race. We are also indebted to Sefton Metropolitan members were filled with great enthusiasm, I suspect that Borough Council for their support, with parking they never thought that the event would still be going arrangements and waste disposal. strong nearly 50 years later. In fact a number of teams Isaac Marsh & Robin Jones from Scammonden Water Sailing Whave competed in virtually every race since then. Club are aiming to complete the full 24 hours to raise money The race originally grew from a 12 hour race, the "British Universities for the Andrew Simpson Sailing Foundation. This charity will Championship", held on the Marine Lake in 1966 and was initially be familiar to everyone in the sailing community and we competed for by the two fleets of Enterprises and GP's. The basic hope you will support this challenge. idea, which has been retained, was for each team's boat to sail around I must also mention the enthusiasm of members of the Marine Lake for twenty four hours, with the one which sailed the Liverpool Yacht Club. -

Commodores Corner –

Spring 18 although the extent of the work required is not yet clear. Commodores Corner – Ian Videlo Similarly, we are advised that the timber part of the retaining wall immediately behind the clubhouse is nearing the end of its life, and should be replaced before it fails. I would like to record my thanks to Alan Hall for getting to grips with this so quickly and also to Haydn Evans and Martin Hawkes for their ongoing professional advice and support. The second area that I would like to I would just like to take the opportunity of highlight is the emergence of a "pathway" this first newsletter of 2018 to bring you model to provide better clarity and focus up to date with some of the key points around our sailing activities here at that are on our agenda. Waldringfield. The pathway itself is modelled on the RYA's "participation Firstly, you will recall that over the past pathway" and should make our offer year or two some very imaginative ideas simpler for a newcomer to understand, have been put forward by two of our and easier for us as established members architect members Charles Curry-Hyde & to explain. Roger Stollery that have the potential to make better use of our club room as well as improve access for the less mobile amongst us. Many of you have already provided informal feedback welcoming many of the suggestions and raising concerns about others. We had intended to conduct a more measured poll of opinion by now, but we have become aware of two more pressing matters which between them could require a significant spend. -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Pennsylvania

Summer 1989 $1.50 Pennsylvania The Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine VIEWPOINT Still a Bargain What does $4 buy today? A meal at a fast food restaurant. Four gallons of gas. A half-case of Coke. A fishing lure. For $6 you can buy a movie ticket, a one-day admission to the community swimming pool or a bleacher seat at a minor league baseball game. What else does $4 and $6 buy? It buys a one-year registration for your boat. And what do you get for that $4 and $6? For starters you get the free use of over 270 boat launching sites. You get the use of 50 Fish Commission-owned lakes. You get free launching on 54 state park lakes and the use of 12 Corps of Engineers impoundments. To make your day safe, you get the services of 71 waterways conservation officers and over 300 deputies. You get special boating regulations to control boat activity. You get over 1,000 aids to navigation to help you know and understand the rules and regulations and to know where the danger spots are. Want your children to learn about boating safety? Try one of the 200 safety programs conducted each year in school districts as part of the Boating and Water Safety Program. How about sending your child through one of the many camp and summer programs taught by Commission volunteers, seasonal employees and full-time staff? Last year over 2,000 children were certified in one of these programs. Are you concerned about the environment? Last year the Bureau of Law Enforcement successfully closed 381 cases against polluters of our waterways resulting in $342,595 in fines. -

Tufts Sailing Magazine

Tufts Sailing Magazine Fall 2015 Welcome to the third annual Tufts Sailing Magazine for alumni, parents, friends and students. We hope this new magazine finds you well and that you are happy to hear our news. We hope to make this magazine informative and attractive enough to keep for years. Inside you will find senior profiles (you might want to hire one of them), alumni interview, schedule, and roster. We are also updating the fund drive for 24 new Larks, to be built right here in Peabody, Massachusetts, USA! In addition to new boats we are seeking donations to increase the educational experience for our team. Combined with a generous budget from the Tufts Athletic Department, your donations will allow the team to keep up with the rising costs of travel, equipment, coaching, and risk management while supporting the biggest and busiest college dinghy team in the world. Photos will of ouse fill a spaes to add a thousad ods. Whethe ou ae a foe college sailor, parent of a college sailor, supporter, or just a friend, enjoy. Ken Legler, Tufts Sailing Coach Contents 2 Coah’s Weloe Lette 3 Fall Season Wrap-up 4 Roster 5 Student Perspectives 7 New Larks for 2016 to 2025 8 Senior Profiles 9 Spring Schedule 10 Alumni Interview with Bill L’ 11 2016 Alumni Regatta announcement Cover: Freshmen and sophomores racing the greatest college dinghies in the world for now. Below: Freshmen sailors Ashley Smith and Logan Russell race upwind on Mystic Lake Fall 2015 Wrap-up This as the fall of feshe. -

MTA13-14 Bk1.Indd

MARINE TRADES ASSOCIATION OF NEW JERSEY Boaterʼs Directory 2014 Edition Table of Contents MTA/NJ Board of Directors and President’s Message .....................................2-3 About MTA/NJ ............................................................................................ 4 Marine Business Directory (alphabetical) .....................................................5-29 Marine Products, Services & Accessories .................................................31-65 (Cross Reference Index/Yellow Pages) Boat Dealerships by Boat Line ..................................................................70-77 Engines (Sales or Service) by Engine Line ..................................................78-86 NJ Pump Out Facilities ............................................................................87-90 Boating Safety Education Requirements .....................................................91-92 Resource Directory .................................................................................93-94 Index of Advertisers .................................................................................... 97 The Marine Trades Association of New Jersey (MTA/NJ) is a non-profi t trade organization dedicated to advancing, promoting and protecting the marine industry and waterways in the State of New Jersey. The MTA/NJ Boaters Directory is provided as a service to its members and the boating public. The MTA/NJ Boater’s Directory includes a listing of all MTA/NJ Members and the products and services that they provide. MTA/NJ does