Public Art/Private Lives A.K.A. Hotel Yeoville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

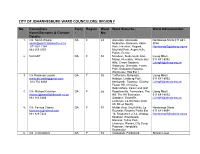

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

Download Yeoville Then And

YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning 2 3 YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning YEOVILLE THEN AND NOW INTRODUCTION BASED IN YEOVILLE, THE GROUP SET OUT IN DOCUMENTING THE PERSONAL HISTORIES OF THE PEOPLE AND THE PLACES THEY’VE LIVED. THEIR JOURNEYS WERE MAPPED INTO AND WITHIN YEO- URBAN (HIS)STORIES VILLE. AFTER THOUROUGH RESEARCH A BRIEF HISTORY OF YEO- VILLE IN THE CONTEXT OF JOHANNESBURG IS PROVIDED. DATA INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY SUCH AS PHOTOGRAPHS, AERIAL MAPS, TIMELINES,PORTRAITS YEOVILLE THEN AND NOW AND WRITTEN TRANSCRIP OF INTERVIEWS OF THE JOURNEY ARE DEMONSTRED. METHODOLOEGY A CLEAR AND PRECISE METHOD OF NETWORKING FLOWS THROUGH THE PROJECT SHOWING A DEFINED MOVEMENT OF THE JOURNEY AND THE RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN YEOVILLE. BY MEANS OF GROUP INTERVIEWS WE WERE ABLE TO SET A COM- FORT LEVEL GAINING MORE CONFIDENCE IN THE INTERVIEWEES AND THEREFORE WERE ABLE TO COLLECT MORE VAST AND DEEP INFORMATION. WE FOUND THIS METHOD EXTREMELY SUCCESFUL AS ONE PERSON BEGAN TO LEAD US TO THE NEXT CREATING A JOURNEY PATH AS WELL AS AN INTERESTING LINE OF INTERAC- TIONS. THERE WAS ALSO AN EMPHASIS PLACED ON BUILDINGS AND THERIR SOCIALAND HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE. arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning arpl 2000 wits school of architecture & planning YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// YEOVILLE STUDIO_housing// 4 5 YEOVILLE NETWORKING In order to understand and analyse a space and the people that move through it one needs to recognize the history and culture of the place in cohesion with the physical and personal now. We must understand the links and connections that form part of the human matrix; how do we communicate, how do we survive amongst each other? These answers coincide within the network that each individu- al shares with another, whether it is a geographical or personal link. -

THE ORDER of APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa

THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg By Mpho Matsipa A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Nezar Alsayyad, Chair Professor Greig Crysler Professor Ananya Roy Spring 2014 THE ORDER OF APPEARANCES Urban Renewal in Johannesburg Mpho Matsipa TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations iii List of Abbreviations vi EAVESDROPPING 1 0.1 Regimes of Representation 6 0.2 Theorizing Globalization in Johannesburg 9 0.2.1 Neo‐liberal Urbanisms 10 0.2.2 Aesthetics and Subject Formation 12 0.2.3 Race Gender and Representation 13 0.3 A note on Methodology 14 0.4 Organization of the Text 15 1 EXCAVATING AT THE MARGINS 17 1.1 Barbaric Lands 18 1.1.1 Segregation: 1910 – 1948 23 1.1.2 Grand Apartheid: 1948 – 1960s 26 1.1.3 Late Apartheid: 1973 – 1990s 28 1.1.4 Post ‐ Apartheid: 1994 – 2010 30 1.2 Locating Black Women in Johannesburg 31 1.2.1 Excavations 36 2 THE LANDSCAPE OF PUBLIC ART IN JOHANNESBURG 39 2.1 Unmapping the City 43 2.1.1 The Dying Days of Apartheid: 1970‐ 1994 43 2.1.2 The Fiscal Abyss 45 2.2 Pioneers of the Cultural Arc 49 2.2.1 City Visions 49 2.2.2 Birth of the World Class African City 54 2.2.3 The Johannesburg Development Agency 58 2.3 Radical Fragments 61 2.3.1 The Johannesburg Art in Public Places Policy 63 3 THE CITY AS A WORK OF ART 69 3.1 Long Live the Dead Queen 72 3.1.2 Dereliction Can be Beautiful 75 3.1.2 Johannesburg Art City 79 3.2 Frontiers 84 3.2.1 The Central Johannesburg Partnership 19992 – 2010 85 3.2.2 City Improvement Districts and the Urban Enclave 87 3.3 Enframing the City 92 3.3.1 Black Woman as Trope 94 3.3.2 Branding, Art and Real Estate Values 98 4 DISPLACEMENT 102 4.1 Woza Sweet‐heart 104 4.1.1. -

Federica Duca-Dissertation March 2015

University of Trento School in Social Sciences Doctoral Program in Sociology and Social Research XXV° Cycle Ph.D. Candidate: Federica Duca Advisor: Prof. Asher Colombo Co-Advisor: Prof. Ivor Chipkin Left outside or trapped in the visible and invisible gate. Insights into the continuities and discontinuities in the creation of good and just living in open and gated suburbs of Johannesburg. April 2015 Abstract Starting from the consideration that gated estates and complexes are increasingly becoming part of the urban, peri-urban and rural landscape of many societies undergoing transformation, the aim of this dissertation is to explore what difference it makes to live in an enclosed space in order to understand not only the choice of living in such environments, but also their spatial, social and political implications and manifestations. This work does so by adopting a relational perspective and by comparing two different neighbourhoods of Johannesburg, South Africa: a newly built gated golf estate (Eagle Canyon) and an old open suburb (Northcliff). In order to develop insights into the ways in which life in a gated community is related to the life outside, an ethnographic study of three years has been carried on in the gated golf estate and in the open suburb. This work argues that gated enclaves, internally organized and managed by specific institutions, not only provide the space in which the "good life" is lead, but most importantly set the standard and the terms of this good life and provide a system of justification for it. Putting in dialogue the two suburbs, this dissertation points out that gated estates provide the sace in which an escalation of belonging takes place. -

Our Areas of Finance Our Branches

OUR BRANCHES OUR AREAS OF FINANCE GAUTENG GAUTENG Johannesburg Pretoria JOHANNESBURG • Hillbrow • Rosettenville 12th Floor, Libridge Building 8th Floor, Olivetti House • Auckland Park • Jeppestown • Rouxville 25 Ameshoff street 100 Pretorius Street • Bellevue • Johannesburg CBD • Selby Braamfontein Cnr Pretorius & Schubart Str • Bellevue East • Joubert Park • Springs CBD Johannesburg, 2001 Pretoria, 0117 • Benoni • Judiths Paarl • Troyeville +27 (10) 595 9000 +27 (10) 595 9000 • Berea • Kempton Park CBD • Turf Club WELCOME • Bertrams • Kenilworth • Turffontein • Bezuidenhout KWAZULU NATAL • Kensington • Westdene Valley • Krugersdorp • Witpoortjie 27th Floor, Embassy Building • Boksburg North • La Rochelle • Yeoville TO TUHF 199 Anton Lembede Street • Braamfontein Durban, 4001 • Langbaagte • Brakpan +27 (31) 306 5036 • Lorentzville PRETORIA • Brixton • Marshall Town • Arcadia • City and Suburban • Melville • Capital Park CBD EASTERN CAPE • Doornfontein • New Doornfontein • Gezina CBD 2nd Floor, BCX Building • Fairview • Newtown • Hatfield 106 Park Drive • Florida • North Doornfontein • Pretoria CBD St. George’s Park • Forest Hill • Orange Grove • Pretoria North CBD Port Elizabeth, 6000 • Germiston • Primrose • Pretoria West +27 (41) 582 1450 • Highlands • Randburg CBD • Silverton CBD • Highlands North • Roodepoort • Sunnyside WESTERN CAPE KWAZULU NATAL 5th Floor South Block, Upper East Side 31 Brickfield Road DURBAN • Montclair • Wentworth Woodstock, • Albert Park • Overport Cape Town, 7925 • Bluff • Pinetown Central PIETERMARITZBURG +27 -

APPENDIX a Historical Overview of the Corridors of Freedom

APPENDIX A_Historical overview of the Corridors of Freedom By Clive Chipkin Geology & Topography GEOLOGY and the 19-century World Market determined the locality of Johannesburg. TOPOGRAPHY contributes significantly to the sense of place, the genius loci, in a region of low hills and linear ridges. Gatsrand, 30 Km to the South; Suikerbosrand, 30 Km to the South East; the Klipriviersberg immediately to the South. In the foreground are the parallel East- West scarps and residue hills of the area magically named the Witwatersrand, looking northwards across a panorama of rolling country and gently sloping valleys to the Magaliesberg horizon – all part of the multiple Johannesburg immersion. Fig. 168 Section of topographical map of Johannesburg. (Source: Office of Surveyor General, Cape Town, surveyed in 1939) The great plains of the continental plateau enters the town-lands: the Houghton- Saxonwold plain north of the ridges and Doornfontein to Turffontein plain occupying the space between the Braamfontein high ground and the Klipriviersberg. The spaciousness – a word used by the visiting geographer JHG Lebon (1952:An Introduction to Human Geography) – of the landscape means that Johannesburg, unlike Durban and Cape Town can expand in almost any direction but after a century plus decades of urban growth, it is our delectable ridges that remain repositories of ancientness. The north facing Parktown ridge with its extension on the Westcliff promontory and its continuation as the Houghton and Orange Grove escarpment to the east 244 Monika Läuferts le Roux & Judith Muindisi, tsica heritage consultants Office: 5th Avenue, 41 – Westdene – 2092 – Johannesburg; Tel: 011 477-8821 [email protected] form a decisive topographical feature defining the major portion of the Northern Suburbs as well and the ancient routes of the wagon roads to the north. -

Self Help Christian Refugees Association

Self Help Christian Refugees Association Ref: Request for support. We would like to appeal to you for a Financial Assistance to support our annual budget in order to provide services to poorest of the poor and neediest and most disadvantaged refugees and local community members who are living without any assistance at Yeoville, Berea, Rosettenville and, Hillbrow and Bertram’s /Johannesburg / South Africa. We are hereby requesting for funding as we are working in the areas faced by the following challenges: 1. Unemployment 2. Crime 3. HIV/AIDS and other STDs 4. Teenagers pregnancy 5. Extreme poverty 6. Xenophobia 7. Lack of skills and knowledge SHCRA is the first Refugees Non- profit Organization, created by refugees themselves with the aim to facilitate a peaceful integration of refugees in South Africa community; we have been involved in community work in Johannesburg some year ago but it still struggling to get potentials founders’ local or international donors to support our work. SHCRA is helping needy community members regardless of Religion, Race, Gender or Nationality Our Vision is: To help needy Refugees and local community members to sustain themselves. Our Mission is: To Assist, to train, and to inform Refugees and local community members so that they can become self sufficient. To improve Social – Economic living conditions of needy refugees and needy local community members, we are focusing our efforts on our objectives. Our Objectives are: Overall Objective: to Facilitate a Peaceful Refugees Integration in the South Africa Society. Education (Assist with education cost for children and refugees youth, Skills Development Training & Job Creation for youth and adult), Emergency Assistance (Accommodation, Food and Cloth distribution to needy most disadvantaged people, Health (HIV / AIDS and STDs Awareness campaign, clinic and hospital support) Reconciliation (Between refugees themselves and with local community; to fight against xenophobia and facilitate good harmony among refugees themselves).