Federica Duca-Dissertation March 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

BUILDING from SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg After Apartheid

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF URBAN AND REGIONAL RESEARCH 471 DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12180 — BUILDING FROM SCRATCH: New Cities, Privatized Urbanism and the Spatial Restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid claire w. herbert and martin j. murray Abstract By the start of the twenty-first century, the once dominant historical downtown core of Johannesburg had lost its privileged status as the center of business and commercial activities, the metropolitan landscape having been restructured into an assemblage of sprawling, rival edge cities. Real estate developers have recently unveiled ambitious plans to build two completely new cities from scratch: Waterfall City and Lanseria Airport City ( formerly called Cradle City) are master-planned, holistically designed ‘satellite cities’ built on vacant land. While incorporating features found in earlier city-building efforts, these two new self-contained, privately-managed cities operate outside the administrative reach of public authority and thus exemplify the global trend toward privatized urbanism. Waterfall City, located on land that has been owned by the same extended family for nearly 100 years, is spearheaded by a single corporate entity. Lanseria Airport City/Cradle City is a planned ‘aerotropolis’ surrounding the existing Lanseria airport at the northwest corner of the Johannesburg metropole. These two new private cities differ from earlier large-scale urban projects because everything from basic infrastructure (including utilities, sewerage, and the installation and maintenance of roadways), -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

West Wits Mining MLI (Pty) Ltd, Roodepoort, Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Gauteng Province

West Wits Mining MLI (Pty) Ltd, Roodepoort, Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Gauteng Province Proposed West Wits Mining Project: Various portions of farms, Vogelstruisfontein 231IQ & 233IQ, Roodepoort 236IQ & 237IQ, Vlakfontein 238IQ, Witpoortjie 245IQ, Uitval 677 IQ, Tshekisho 710 IQ, Roodepoort Magisterial District, Gauteng Heritage Impact Assessment Issue Date: 17 May 2019 Revision No.: 0.4 PGS Project No.: 298 HIA + 27 (0) 12 332 5305 +27 (0) 86 675 8077 [email protected] PO Box 32542, Totiusdal, 0134 Offices in South Africa, Kingdom of Lesotho and Mozambique Head Office: 906 Bergarend Streets Waverley, Pretoria, South Africa Directors: HS Steyn, PD Birkholtz, W Fourie Declaration of Independence ▪ I, Jennifer Kitto, declare that – ▪ General declaration: ▪ I act as the independent heritage practitioner in this application; ▪ I will perform the work relating to the application in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the applicant; ▪ I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; ▪ I have expertise in conducting heritage impact assessments, including knowledge of the Act, Regulations and any guidelines that have relevance to the proposed activity; ▪ I will comply with the Act, Regulations and all other applicable legislation; ▪ I will take into account, to the extent possible, the matters listed in section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA) Act 25 of 1999, when preparing the application and any report -

Johannesburg Botanical Gardens)

Mammal Habitat Scan of the The Remainder of the farm Braamfontein 53-IR (Johannesburg Botanical Gardens) October 2016 Report author: I.L. Rautenbach (Ph.D., T.H.E.D., Pr.Sci.Nat.) Mammal Scan: Johannesburg Botanical Gardens October 2016 1 of 10 pages TABLE OF CONTENTS Declaration of Professional Standing and Independence: ............................................... 3 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 4 2. SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY .......................................................... 4 3. STUDY AREA ........................................................................................................... 4 4. METHODS ................................................................................................................ 7 5. RESULTS ................................................................................................................. 7 5.1 Mammal Habitat Assessment ............................................................................. 7 5.2 Expected and Observed Mammal Species Richness ......................................... 7 5.3 Threatened and Red Listed Mammal Species Flagged ..................................... 8 6. FINDINGS AND POTENTIAL IMPLICATIONS ......................................................... 8 7. LIMITATIONS, ASSUMPTIONS AND GAPS INFORMATION .................................. 8 8. RECOMMENDED MITIGATION MEASURES .......................................................... 9 9. CONCLUSIONS -

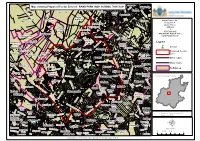

Map Showing Proposed Feeder Zone Of

n Nooitgedacht Bloubosrand e Fourways Kya Sand SP p D p o MapA sHhowing Proposed Feeder Zone of : RAND PARK HIGo H SCJHohOanOneLsb 7ur0g0151241 lie Magaliessig tk u s B i North g e Hoogland l L W e W a y s Norscot i e ll r Cosmo City ia s Noordhang Jukskei m N a n i N a r Park u Douglasdale i d a c é o M North l Rietfontein AH Sonnedal AH Riding AH Bryanston District Name: JN Circuit No: 4 North Riding G ro Cluster No: 2 sv Bellairs Park en Jackal or Address: Creek Golf Northworld AH d 1 J n a a Estate Olivedale c l ASSGAAI AVE a r n r o Northgate a e t n b s RANDPARK RIDGE EXT1 Zandspruit SP da n m a u y Rietfontein AH r RANDPARK RIDGE Sharonlea C s B n y Vandia i a H a o Sundowner Hunters K Grove m M e e Zonnehoewe AH Hill A. h s Roodekrans Ext c t Legend u e H. SP o Beverley a AH F d Country s. e Gardens er r Life Ruimsig Noord et P School P Bryanbrink Park Sundowner Northworld Sonneglans Tres Jolie AH Laser Park t Kensington B Proposed Feeder r ord E Alsef AH a xf t Ruimsig w O o Zone Ruimsig AH .S Strijdompark n Lyme Park .R Ambot AH C Bond Bromhof H New Brighton a Other roads n s Boskruin Eagle Canyon s Schoeman S Han t Hill Ferndale Kimbult AH r ij Major roads Poortview t d Hurlingham e ut o Willowbrook ho m AH W r d Bordeaux e Harveston AH st Malanshof r e Y e r d o Willowild Subplaces uge R Kr Randpark ep w ul n ub Pa lic r a s e a Ridge Ruiterhof h i R V c t a Amorosa Aanwins AH i ic b N r Honeydew s ie k i i Glenadrienne SP1 e r r d e Ridge h President d i Jo Moret n Craighall Locality in Gauteng Province C hn Vors Fontainebleau D ter Ridge e H J Wilro Wilgeheuwel a J n Radiokop . -

Post Doc Position for UNIVERSITY of JOHANNESBURG, Faculty of Science, Department of Physics

HEP (ATLAS) Post Doc Position for UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG, Faculty of Science, Department of Physics The Physics Department seeks to appoint a Post Doctoral Research Fellow in Experimental High Energy Physics (HEP) at its Auckland Park Kingsway Campus. See http://www.slac.stanford.edu/spires/find/jobs/www?irn=79464 Applications are welcomed. The University of Johannesburg is a founding member of the SA-ATLAS group and is also part of the SA-CERN Programme. The group currently comprises two staff members and three graduate (Phd, MSc) students. The group is working closely with Ketevi Assamagan (co-convenor of the Higgs working group), focusing on Higgs and SUSY physics with an emphasis on the muon sector. The HEP research infrastructure includes the University of Johannesburg Research Cluster (280 cores, 8GB storage) which is a component of South African National Grid with both OSG and gLite interoperability. This cluster is currently in the process of becoming an ATLAS - Tier 3 site attached to BNL. The successful applicant is expected to conduct their own research within the area mentioned above as well as to mentor the students in the group. An on-site visit to CERN of an aggregate period of at least 6 months per year is included. The duration of the Post Doc funding is two years and can be extended by application for additional years. The Physics Department has 21 teaching members, and the successful Post Doc candidate would be welcome to consider a small teaching load if they wish to. The University is situated in the leafy suburbs of Johannesburg North, in a cosmopolitan area in excellent relationship to all services and facilities of a modern city. -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

The Value of Tours Around Heritage Sites with Melville Koppies As an Example

1 The value of tours around heritage sites with Melville Koppies as an example Wendy Carstens Melville Koppies Nature Reserve and Joburg Heritage Site [email protected] Abstract Tours enrich and reinforce textbook and classroom history, inspire further study, and promote an appreciation of past cultures. This paper discusses the value of guided tours on Melville Koppies, a Nature Reserve and Johannesburg Heritage Site. Melville Koppies offers evidence of man-made structures and artefacts reflecting Pre-History from Early Stone Age to Iron Age in this undeveloped pristine reserve where the natural sciences and social sciences meet. The site includes evidence of gold mining attempts, the Second Anglo-Boer War and modern history up to present times. The panoramic view from the top ridges of the Koppies encompasses places of rich historical interest, of which many, such as Sophiatown and Northcliff Ridge, were affected by apartheid. Guided tours are tailored to educators’ requirements and the age of students. These educators usually set their own pre- or post-tour tasks. The logistical challenges for educators of organising such three-hour tours are discussed. History, if part of a life-time awareness, is not confined to primary, secondary or tertiary learners. Further education for visitors of all ages on guided tours is also discussed Key words: Wealth of evidence; Social and natural sciences meet; Guided tours; Enrichment Introduction The content of even the most dynamic History lectures may be forgotten in time. However, if lectures are followed up by tours to relevant heritage sites that complement the lectures, this reinforces and enriches the learning experience. -

(Legal Gazette A) Vol 669 No 44290

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant March Vol. 669 19 2021 No. 44290 Maart PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5845 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 44290 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 44290 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 19 MARCH 2021 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES / WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 14 ORDERS OF THE COURT • BEVELE VAN DIE HOF National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 16 GENERAL • ALGEMEEN National / Nasionaal .................................................................................................................................. 29 ADMINISTRATION OF ESTATES ACTS NOTICES / BOEDELKENNISGEWINGS Form/Vorm J295 ...................................................................................................................................................