Conceiving, Producing and Managing Neighbourhoods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germiston South Jurisdiction:- Airport; Albermarle; Asiatic Bazaar; Buhle

Germiston South Jurisdiction:- Airport; Albermarle; Asiatic Bazaar; Buhle Park; Castleview; Cruywagenpark; Dallas Station; Delmenville; Delport; Delville; Denlee; Dewittsrus; Dikatole; Dinwiddie; Driehoek; Egoli Village; Elandshaven; Elsburg; Elspark; Estera; Geldenhuys; Georgetown; Germistoin Industries East; Germiston Industries West; Germiston Lake; Germiston South; Germiston West; Goodhope; Gosforth Park; Graceland; Hazeldene; Hazelpark; Herriotdale; Junction Hill; Jupiter Park Ext 3; Klippoortjie; Klippoortjie Agricultiural Lots; Klippoortjie Park; Knights; Kutalo Hostel; Lake Park; Lambton; Lambton Gardens; Marathon; Mimosa Park; Parkhill Gardens; Pharo Park; Pirowville; Rand Airport; Rondebult; Simmerpan; Summerpark; Tedstoneville; Union Settlements; Wadeville; Webber Germiston North Jurisdiction :- Activia Park; Barvallen; Bedford Gardens; Bedford Park; Bedfordview; Buurendal; Clarens Park; Creston Hill; Dania Park; Dawnview; De Klerkshof; Dowerglen; Dunvegan; Eastliegh; Edenglen; Edenvale; Elandsfontein; Elma Park; Elsieshof; Essexwold; Fisher's Hill; Garden View; Gerdview; Germiston North; Glendower; Greenhills Estate; Harmelia; Henville; Highway Gardens; Homestead; Hurleyvale; Illiondale; Isandovale; Klopperpark; Kruinhof; Malvern East; Maquaksi Plakkers Kamp; Marais-Steyn Park; Marlands; Meadowdale; Morninghill; Oriel; Primrose; Primrose Hill; Primrose Ridge; Rietfontein Hospital; River Ridge; Rustivia; Sebenza; Senderwood; Simmerfield; Solheim; St.Andrews & Exts./Uit; Sunnyridge; Sunnyrock; Symhurst; Symridge; Tunney; Veganview; -

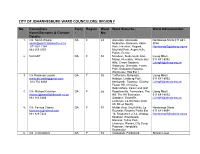

City of Johannesburg Ward Councillors: Region F

CITY OF JOHANNESBURG WARD COUNCILLORS: REGION F No. Councillors Party Region Ward Ward Suburbs: Ward Administrator: Name/Surname & Contact : : No: Details: 1. Cllr. Sarah Wissler DA F 23 Glenvista, Glenanda, Nombongo Sitela 011 681- [email protected] Mulbarton, Bassonia, Kibler 8094 011 682 2184 Park, Eikenhof, Rispark, [email protected] 083 256 3453 Mayfield Park, Aspen Hills, Patlyn, Rietvlei 2. VACANT DA F 54 Mondeor, Suideroord, Alan Lijeng Mbuli Manor, Meredale, Winchester 011 681-8092 Hills, Crown Gardens, [email protected] Ridgeway, Ormonde, Evans Park, Booysens Reserve, Winchester Hills Ext 1 3. Cllr Rashieda Landis DA F 55 Turffontein, Bellavista, Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Haddon, Lindberg Park, 011 681-8092 083 752 6468 Kenilworth, Towerby, Gillview, [email protected] Forest Hill, Chrisville, Robertsham, Xavier and Golf 4. Cllr. Michael Crichton DA F 56 Rosettenville, Townsview, The Lijeng Mbuli [email protected] Hill, The Hill Extension, 011 681-8092 083 383 6366 Oakdene, Eastcliffe, [email protected] Linmeyer, La Rochelle (from 6th Street South) 5. Cllr. Faeeza Chame DA F 57 Moffat View, South Hills, La Nombongo Sitela [email protected] Rochelle, Regents Park& Ext 011 681-8094 081 329 7424 13, Roseacre1,2,3,4, Unigray, [email protected] Elladoon, Elandspark, Elansrol, Tulisa Park, Linmeyer, Risana, City Deep, Prolecon, Heriotdale, Rosherville 6. Cllr. A Christians DA F 58 Vredepark, Fordsburg, Sharon Louw [email protected] Laanglagte, Amalgam, 011 376-8618 011 407 7253 Mayfair, Paginer [email protected] 081 402 5977 7. Cllr. Francinah Mashao ANC F 59 Joubert Park Diane Geluk [email protected] 011 376-8615 011 376-8611 [email protected] 082 308 5830 8. -

Are Johannesburg's Peri-Central Neighbourhoods Irremediably 'Fluid'?

Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams Claire Bénit-Gbaffou To cite this version: Claire Bénit-Gbaffou. Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Lo- cal leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams. Harrison P, Gotz G, Todes A, Wray C (eds), Changing Space, Changing City., Wits University Press, pp.252-268, 2014, 10.18772/22014107656.17. hal-02780496 HAL Id: hal-02780496 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02780496 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 13 Are Johannesburg’s peri-central neighbourhoods irremediably ‘fluid’? Local leadership and community building in Yeoville and Bertrams CLAIRE BÉNIT-gbAFFOU Johannesburg’s inner city is a convenient symbol in contemporary city culture for urban chaos, unpredictability, endless mobility and undecipherable change – as emblematised by portrayals of the infamous Hillbrow in novels and movies (Welcome to our Hillbrow, Room 207, Zoo City, Jerusalema)1 and in academic literature (Morris 1999; Simone 2004). Inner-city neighbourhoods in the CBD and on its immediate fringe (or ‘peri-central’ areas) currently operate as ports of entry into South Africa’s economic capital, for both national and international migrants. -

7.5. Identified Sites of Significance Residential Buildings Within Rosettenville (Semi-Detached, Freestanding)

7.5. Identified sites of significance_Residential buildings within Rosettenville (Semi-detached, freestanding) Introduction Residential buildings are buildings that are generally used for residential purposes or have been zoned for residential usage. It must be noted the majority of residences are over 60 years, it was therefore imperative for detailed visual study to be done where the most significant buildings were mapped out. Their significance could be as a result of them being associated to prominent figures, association with special events, design patterns of a certain period in history, rarity or part of an important architectural school. Most of the sites identified in this category are of importance in their local contexts and are representative of the historical and cultural patterns that could be discerned from the built environment. All the identified sites were given a 3A category explained below. Grading 3A_Sites that have a highly significant association with a historic person, social grouping, historic events, public memories, historical activities, and historical landmarks (should by all means be conserved) 3B_ Buildings of marginally lesser significance (possibility of senstive alteration and addition to the interior) 3C_Buildings and or sites whose significance is in large part significance that contributes to the character of significance of the environs (possibility for alteration and addition to the exterior) Summary Table of identified sites in the residential category: Site/ Description Provisional Heritage Implications -

Braamfontein Aims to Be National Digital Hub

Views, Comments and Opinion Braamfontein aims to be national digital hub by Hans van de Groenendaal, features editor Prof. Barry Dwolatzky, director of the the Joburg Centre for Sofware Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand believes in the value of an attractive and vibrant digital technolgy hub in Braamfontein to support skills development, job creation, entrepreneurship and the rejuvenation of Johanesburg's inner city. Braamfontein has seen much urban renewal in recent times, and is begining to regain its erstwhile trendiness. Prof. Barry Dwolatzky calls this new digital development the Tshimologong Precinct and is planning to create an exciting new-age software skills and innovation hub. Tshimologong is the seSotho for "place of new beginnings". The precinct is part of an ambitious ICT cluster development programme, Tech-in-Braam, aimed at turning the once dilapidated suburb into the new technical heart of South Africa and beyond. Prof. Dwolatzky is in the process of setting up shop in a series of five unused buildings. After some extensive refurbishments, a one-time night club floor will become a meeting space and will house server rooms; warehouses will be converted into computer labs and retail outlets will reincarnate as development pods. Braamfontein’s many advantages have made the neighbourhood an obvious The Tshimologong precinct will be developed in this part of Braamfontein. location for the precinct – it is convenient to two universities (the University of the Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg); it is centrally located with good public transport; it is the site of local government departments and many non-governmental organisations; and it is within easy reach of banks and mining houses, as well as a multitude of corporate headquarters. -

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa

Middle Classing in Roodepoort Capitalism and Social Change in South Africa Ivor Chipkin June 2012 / PARI Long Essays / Number 2 Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... 3 Preface ........................................................................................................ 5 Introduction: A Common World ................................................................. 7 1. Communal Capitalism ....................................................................... 13 2. Roodepoort City ................................................................................ 28 3.1. The Apartheid City ......................................................................... 33 3.2. Townhouse Complexes ............................................................... 35 3. Middle Class Settlements ................................................................... 41 3.1. A Black Middle Class ..................................................................... 46 3.2. Class, Race, Family ........................................................................ 48 4. Behind the Walls ............................................................................... 52 4.1. Townhouse and Suburb .................................................................. 52 4.2. Milky Way.................................................................................. 55 5. Middle-Classing................................................................................. 63 5.1. Blackness -

Alexandra Urban Renewal:- the All-Embracing Township Rejuvenation Programme

ALEXANDRA URBAN RENEWAL:- THE ALL-EMBRACING TOWNSHIP REJUVENATION PROGRAMME 1. Introduction and Background About the Alexandra Township The township of Alexandra is one of the densely populated black communities of South Africa reach in township culture embracing cultural diversity. This township is located about 12km (about 7.5 miles) north-east of the Johannesburg city centre and 3km (less than 2 miles) from up market suburbs of Kelvin, Wendywood and Sandton, the financial heart of Johannesburg. It borders the industrial areas of Wynberg, and is very close to the Limbro Business Park, where large parts of the city’s high-tech and service sector are based. It is also very near to Bruma Commercial Park and one of the hype shopping centres of Eastgate Shopping Centre. This township amongst the others has been the first stops for rural blacks entering the city in search for jobs, and being neighbours with the semi-industrial suburbs of Kew and Wynberg. Some 170 000 (2001 Census: 166 968) people live in this community, in an area of approximately two square kilometres. Alexandra extends over an area of 800 hectares (or 7.6 square kilometres) and it is divided by the Jukskei River. Two of the main feeder roads into Johannesburg, N3 and M1 pass through Alexandra. However, the opportunity to link Alexandra with commercial and industrial areas for some time has been low. Socially, Alexandra can be subdivided into three parts, with striking differences; Old Alexandra (west of the Jukskei River) being the poorest and most densely populated area, where housing is mainly in informal dwellings and hostels. -

City of Johannesburg Pikitup

City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za DEPOT SUBURB/TOWNSHIP PRIORITY AREAS TO BE CLEARED ON FRIDAY, 05 FEB 2016 AVALON DEPOT Eldorado Park Ext 2 and Eldorado Park Proper (Michael Titus 083 260 1776) Eldorado Park Ext 10 and Proper Eldorado Park Ext 1, 3, and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 6 and 4 Eldorado Park Ext 4, Proper and Nancefield Industria Eldorado Park Ext 2, 3 and Bushkoppies Eldorado Park Ext 4 and Proper Eldorado Park Proper and M/Park Orange Farm Ext 3 and 1 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Ext 1 and 2 Orange Farm Proper CENTRAL CAMP Selinah Pimville Zones 1 - 4 Tshablala 071 8506396 MARLBORO DEPOT Buccleuch ‘Nyane Motaung - 071 850 6395 Sandown City of Johannesburg Pikitup Pikitup Head Office Private Bag X74 Tel +27(0) 11 712 5200 66 Jorissen Place, Jorissen St, Braamfontein Fax +27(0) 11 712 5322 Braamfontein Johannesburg www.pikitup.co.za 2017 2017 www.joburg.org.za MIDRAND DEPOT Cresent wood, Erands gardens, Erands AH and Noordwyk South Jeffrey Mahlangu 082 492 8893 Juskeyview, Waterval estate, South , west and north NORWOOD DEPOT Bruma (Neil Observatory Macherson 071 Kensington 682 1450) Yeoville RANDBURG DEPOT Majoro Letsela Blairgowrie 082 855 9348 ROODEPOORT DEPOT Stella Wilson - Florida 071 856 6822 SELBY DEPOT Fordsburg Sobantwana Mkhuseli CBD 1: (Noord to Commissioner & End to Rissik Streets) 082 855 9321 CBD 2: (Rissik to -

Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City Of

19 July 2013: Metropolis in Sophiatown Today, the Executive Mayor of the City of Johannesburg, Cllr Mpho Parks Tau, launched an Xtreme Park in Sophiatown while closing the annual Metropolis 2013 meeting held in Sandton, Joburg from Tuesday. At the launch, the Executive Mayor paid tribute to the vibrancy, multi-cultural and multi-racial buoyancy of Sophiatown, a place that became the lightning rod of both the anti-apartheid movement as well as the apartheid government's racially segregated and institutionalised policy of separate development. In February 1955 over 65 000 residents from across the racial divide were forcibly removed from Sophiatown and placed in separate development areas as they were considered to be too close to white suburbia. Sophiatown received a 48 hour Xtreme Park makeover courtesy of the City as part of its urban revitalisation and spatial planning programme. Said Mayor Tau: "The Xtreme Park concept was directed at an unused piece of land and turning it into a luscious green park. The park now consists of water features, play equipment for children, garden furniture and recreational facilities. Since 2007 the city has completed a number of Xtreme Parks in various suburbs including Wilgeheuwel, Diepkloof, Protea Glen, Claremont, Pimville and Ivory Park. As a result, Joburg's City Parks was awarded a gold medal by the United Nations International Liveable Communities award in 2008. "Today we are taking the Xtreme Parks concept into Sophiatown as part of our urban revitalisation efforts in this part of the city. Our objective is to take an under- utilised space, that is characterized by illegal dumping, graffiti, and often the venue for petty crime and alcohol and drug abuse; and transform it into a fully-fledged, multi-functional park," the Mayor said. -

Memories of Johannesburg, City of Gold © Anne Lapedus

NB This is a WORD document, you are more than Welcome to forward it to anyone you wish, but please could you forward it by merely “attaching” it as a WORD document. Contact details For Anne Lapedus Brest [email protected] [email protected]. 011 783.2237 082 452 7166 cell DISCLAIMER. This article has been written from my memories of S.Africa from 48 years ago, and if A Shul, or Hotel, or a Club is not mentioned, it doesn’t mean that they didn’t exist, it means, simply, that I don’t remember them. I can’t add them in, either, because then the article would not be “My Memories” any more. MEMORIES OF JOHANNESBURG, CITY OF GOLD Written and Compiled By © ANNE LAPEDUS BREST 4th February 2009, Morningside, Sandton, S.Africa On the 4th February 1961, when I was 14 years old, and my brother Robert was 11, our family came to live in Jhb. We had left Ireland, land of our birth, leaving behind our beloved Grandparents, family, friends, and a very special and never-to-be-forgotten little furry friend, to start a new life in South Africa, land of Sunshine and Golden opportunity…………… The Goldeneh Medina…... We came out on the “Edinburgh Castle”, arriving Cape Town 2nd Feb 1961. We did a day tour of Chapmans Peak Drive, Muizenberg, went to somewhere called the “Red Sails” and visited our Sakinofsky/Yodaiken family in Tamboerskloof. We arrived at Park Station (4th Feb 1961), Jhb, hot and dishevelled after a nightmarish train ride, breaking down in De Aar and dying of heat. -

![Our Hillbrow, Not Only to Move in and out of the “Physical and the Metaphysical Sphere[S]” Effectively but Also to Employ a Communal Mode of Narrative Continuity](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3689/our-hillbrow-not-only-to-move-in-and-out-of-the-physical-and-the-metaphysical-sphere-s-effectively-but-also-to-employ-a-communal-mode-of-narrative-continuity-733689.webp)

Our Hillbrow, Not Only to Move in and out of the “Physical and the Metaphysical Sphere[S]” Effectively but Also to Employ a Communal Mode of Narrative Continuity

Introduction ghirmai negash haswane Mpe (1970–2004) was one of the major literary talents to emerge in South PAfrica after the fall of apartheid. A graduate in African literature and English from the Univer- sity of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, he was a nov- elist, poet, scholar, and cultural activist who wrote with extraordinary commitment and originality, both in substance and in form. His intellectual honesty in exploring thematic concerns germane to postapartheid South African society continues to inspire readers who seek to reflect on old and new sets of problems facing the new South Africa. And his style continues to set the bar for many aspiring black South African writers. Mpe’s writing is informed by an oral tradition par- ticular to the communal life of the South African xii Introduction pastoral area of Limpopo. This, in addition to his modern university liberal arts education; his experi- ence of urban life in Johannesburg; and, ultimately, his artistic sensibility and ability to synthesize dis- parate elements, has marked him as a truly “home- grown” South African literary phenomenon. It is no wonder that the South African literary commu- nity was struck by utter shock and loss in 2004 when the author died prematurely at the age of thirty- four. In literary historical terms, Mpe’s early death was indeed a defining moment.I n an immediate way, his South African compatriots—writers, critics, and cultural activists—were jolted into awareness of what the loss of Mpe as a unique literary fig- ure meant for South African literary tradition. In terms of his legacy, it was also a moment of acute revelation that the force and form of his work was a motivating influence for, just as it was inspired by, the emergence of many more writers of consider- able talent. -

Department of Human Settlements Government Gazette No

Reproduced by Data Dynamics in terms of Government Printers' Copyright Authority No. 9595 dated 24 September 1993 671 NO. 671 NO. Priority Housing Development Areas Department of Human Settlements Housing Act (107/1997): Proposed Priority Housing Development Areas HousingDevelopment Priority Proposed (107/1997): Act Government Gazette No.. I, NC Mfeketo, Minister of Human Settlements herewith gives notice of the proposed Priority Housing Development Areas (PHDAs) in terms of Section 7 (3) of the Housing Development Agency Act, 2008 [No. 23 of 2008] read with section 3.2 (f-g) of the Housing Act (No 107 of 1997). 1. The PHDAs are intended to advance Human Settlements Spatial Transformation and Consolidation by ensuring that the delivery of housing is used to restructure and revitalise towns and cities, strengthen the livelihood prospects of households and overcome apartheid This gazette isalsoavailable freeonlineat spatial patterns by fostering integrated urban forms. 2. The PHDAs is underpinned by the principles of the National Development Plan (NDP) and allied objectives of the IUDF which includes: DEPARTMENT OFHUMANSETTLEMENTS DEPARTMENT 2.1. Spatial justice: reversing segregated development and creation of poverty pockets in the peripheral areas, to integrate previously excluded groups, resuscitate declining areas; 2.2. Spatial Efficiency: consolidating spaces and promoting densification, efficient commuting patterns; STAATSKOERANT, 2.3. Access to Connectivity, Economic and Social Infrastructure: Intended to ensure the attainment of basic services, job opportunities, transport networks, education, recreation, health and welfare etc. to facilitate and catalyse increased investment and productivity; 2.4. Access to Adequate Accommodation: Emphasis is on provision of affordable and fiscally sustainable shelter in areas of high needs; and Departement van DepartmentNedersettings, of/Menslike Human Settlements, 2.5.