An Analysis of Clean Water Act Compliance, July 2003- December 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5

NON-TIDAL BENTHIC MONITORING DATABASE: Version 3.5 DATABASE DESIGN DOCUMENTATION AND DATA DICTIONARY 1 June 2013 Prepared for: United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, Maryland 21403 Prepared By: Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 Prepared for United States Environmental Protection Agency Chesapeake Bay Program 410 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD 21403 By Jacqueline Johnson Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin To receive additional copies of the report please call or write: The Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin 51 Monroe Street, PE-08 Rockville, Maryland 20850 301-984-1908 Funds to support the document The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.0; Database Design Documentation And Data Dictionary was supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency Grant CB- CBxxxxxxxxxx-x Disclaimer The opinion expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed as representing the U.S. Government, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the several states or the signatories or Commissioners to the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin: Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia or the District of Columbia. ii The Non-Tidal Benthic Monitoring Database: Version 3.5 TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Gazetteer of West Virginia

Bulletin No. 233 Series F, Geography, 41 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIKECTOU A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA I-IEISTRY G-AN3STETT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 A» cl O a 3. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. DEPARTMENT OP THE INTEKIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. C. , March 9, 190Jh SIR: I have the honor to transmit herewith, for publication as a bulletin, a gazetteer of West Virginia! Very respectfully, HENRY GANNETT, Geogwvpher. Hon. CHARLES D. WALCOTT, Director United States Geological Survey. 3 A GAZETTEER OF WEST VIRGINIA. HENRY GANNETT. DESCRIPTION OF THE STATE. The State of West Virginia was cut off from Virginia during the civil war and was admitted to the Union on June 19, 1863. As orig inally constituted it consisted of 48 counties; subsequently, in 1866, it was enlarged by the addition -of two counties, Berkeley and Jeffer son, which were also detached from Virginia. The boundaries of the State are in the highest degree irregular. Starting at Potomac River at Harpers Ferry,' the line follows the south bank of the Potomac to the Fairfax Stone, which was set to mark the headwaters of the North Branch of Potomac River; from this stone the line runs due north to Mason and Dixon's line, i. e., the southern boundary of Pennsylvania; thence it follows this line west to the southwest corner of that State, in approximate latitude 39° 43i' and longitude 80° 31', and from that corner north along the western boundary of Pennsylvania until the line intersects Ohio River; from this point the boundary runs southwest down the Ohio, on the northwestern bank, to the mouth of Big Sandy River. -

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No

TROUT Stocking – Lakes and Ponds Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Code No. Stockings .......Period Q One ...........................1st week of March Twice a month .............. February-April CR Varies ...........................................Varies BW One ........................................... January M One each month ........... February-May One .................................................. May W Two..........................................February MJ One each month ............January-April One ........................................... January One each week ....................March-May Y One ................................................. April BA One each week ...................................... X After April 1 or area is open to public One ...............................................March F weeks of October 19 and 26 Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Lake or Pond ‒ County Code Anawalt – McDowell M Laurel – Mingo MJ Anderson – Kanawha BA Lick Creek – Wayne MJ Baker – Ohio Q Little Beaver – Raleigh MJ Barboursville – Cabell BA Logan County Airport – Logan Q Bear Rock Lakes – Ohio BW Mason Lake – Monongalia M Berwind – McDowell M Middle Wheeling Creek – Ohio BW Big Run – Marion Y Miletree – Roane BA Boley – Fayette M Mill Creek – Barbour M Brandywine – Pendleton BW-F Millers Fork – Wayne Q Brushy Fork – Pendleton BW Mountwood – Wood MJ Buffalo Fork – Pocahontas BW-F Newburg – Preston M Cacapon – Morgan W-F New Creek Dam 14 – Grant BW-F Castleman Run – Brooke, Ohio BW Pendleton – Tucker -

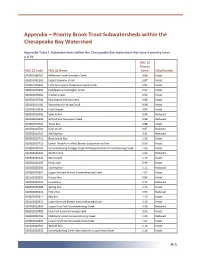

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Potomac Headwaters Water Quality Report July 1998 - June 2008

West Virginia Department of Agriculture Gus R. Douglass, Commissioner Regulatory and Environmental Affairs Division West Virginia’s Potomac Headwaters Water Quality Report July 1998 - June 2008 Chesapeake Bay Program A Watershed Partenership *** West Virginia Department of Agriculture 60B Moorefield Industrial Park Road Moorefield, West Virginia 26836 304/538-2397 http://www.wvagriculture.org/ Maps created and report statistically analyzed and written by Amanda Sullivan, West Virginia Department of Agriculture Cover photos of the South Branch Potomac River taken by Kristy Strickler, West Virginia Department of Agriculture Funded by the West Virginia Department of Agriculture and the Chesapeake Bay Progarm Printed by the West Virginia Department of Agriculture, Communications Division he mission of the West Virginia Department of Agriculture is to protect Tplant, animal and human health and the state’s food supply through a variety of scientific and regulatory programs; to provide vision, strategic planning and emergency response for agricultural and other civil emergencies; to promote industrial safety and protect consumers through educational and regulatory programs; and to foster economic growth by promoting West Virginia agriculture and agribusinesses throughout the state and abroad. MISSION STATEMENT - 1 - Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................3 Forward .................................................................................................................4 -

Potomac Stream Samplers

2007 Data Report Potomac Stream Samplers Caring for Our Watersheds from the Mountains to the Sea A project of The Mountain Institute, in cooperation with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Image from the Potomac Conservancy website) Table of Contents About the Potomac Stream Samplers Program 3 Explanation of the data 4 Data summaries Big Run (Professional development workshop and student field trips) 8 Un-named tributary of Back Creek: Musselman High School 12 Patterson Creek: Frankfort Middle School 14 Conococheague Creek: Spring Mills Middle School Science Club 16 Potomac River: Spring Mills Middle School Science Club 16 Laurel Hill Creek: Rockwood High School 19 Bakers Run: East Hardy Middle/High School 21 Blackthorn Creek: Pendleton County Middle School 23 Whitethorn Creek: Pendleton County Middle School 26 Stream Status Maps 2007 29 2004 - 2007 30 Stream survey history 31 Photographs and participants list Professional development workshop 33 Musselman High School 35 Frankfort Middle School 37 Spring Mills Middle School Science Club 39 Rockwood High School 41 East Hardy Middle/High School 43 Pendleton County Middle School 45 About the Potomac Stream Samplers Program In 2004, The Mountain Institute (TMI) received funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to implement a watershed education project involving students and educators who live in West Virginia’s Potomac River watershed. As part of a broader effort to educate the public about the compromised and increasingly stressed health of the Chesapeake Bay, Potomac Stream Samplers was designed by TMI to raise awareness of the connection between regions within the Potomac River drainage and the Bay itself. -

Traveltime and Dispersion of a Soluble Dye in the South Branch Potomac River, Petersburg to Green Spring, West Virginia

TRAVELTIME AND DISPERSION OF A SOLUBLE DYE IN THE SOUTH BRANCH POTOMAC RIVER, PETERSBURG TO GREEN SPRING, WEST VIRGINIA By Alvin R. Jack U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water Resources Investigations Report 84-4167 Prepared in cooperation with the INTERSTATE COMMISSION ON THE POTOMAC RIVER BASIN Charleston, West Virginia 1986 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, SECRETAR Y GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Open-File Services Section 603 Morris Street Western Distribution Branch Charleston, West Virginia 25301 U.S. Geological Survey Box 25425, Federal Center Denver, Colorado 80225 (Telephone: (303) 234-5888) CONTENTS Page Abstract.. .............................................................................................. .. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Description of the reach................................................................................................................ 1 Methods of study........................................................................................................................3 Traveltime determinations........................................................................................................4 Discharge determinations.........................................................................................................4 -

West Virginia Conservation Agency

West Virginia Conservation Agency Putting Technology to Work To Improve Inspections, Operation and Maintenance Program West Virginia Flood Control Structures HARMON CREEK 3HARMON CREEK 4 HARMON CREEK!..!!..!1!.HARMON CREEK 2 WHEELING CREEK 7 .! !. Northern Panhandle !..! .! WHEELING CREEK 2 WHEELING CREEK 3 UPPER GRAVE CREEK!..!!..!5.! UPPER GRAVE CREEK 9 ! UPPER GRAVE CREEK 8 UPPER GR VE CREEK 7 WARM SPRINGS RU !.7 .! !.!. !.! WWAARRMMSPSPRRINGINGSSRUNRUN69 UPPER BUFFALO C!.REEK 39 !.!. Monongahela WARM SPRIN S RUN 5 !. ! PATTERSON CREEK 50.! Upper Ohio .! .! !. .!!.!..! !.!. UPPER DECKERS CREEK 7NEW CREEK 16 EW CREEK 1 Eastern Panhandle .!!. !. .! NEW CREEK!. 7N!.EW.!!.CREEK 9 NEW CRE K 10 .!!. NE.!W.!.! CREEK 5 POND UN 1 ..! ..! .! SALEM FORK 15 NEW.! CREEK 17 !. !. !.!. SALEM FORK 9 NEW CREEK!. 14 !. .!!. SALEM FORK 13 !...! .! NEW. CREEK 12 .! PATTERSON CREEK 6 !. NORTH FORK OF HUGH!. ES RIVE!. R PULLMAN 1 SALEM FORK 14 !. !.!.PATTERSON CREEK 4 WALKER CREEK ECREATION IMPOUNDMENT .! LUNICE CREEK 11 .! .! West Fork !.LUN!.ICE CREEK 9 !.!. .!!..! Little Kanawha POLK CREEK 6 POLK CREEK 9 LUNICE CREEK 10 !.!.!..!. Potomac Va!.lley District # of FCS SOUTH FORK POLK CREEK 7POLK CREEK 8 !. !1SOUTH.! FOR Tygarts Valley . 2 !. !. !. SOUTH F RK 4 SOUTH FOR!. K 5.! !. Capitol 4 MILL CREEK 8MILL CREEK 9 MILL CREEK 4!. .! !. !. SOUTH FORK 6 !. !.MILL CR!.EEK 5 SOUTH FORK 3.!7 .! MILL CREEK 13 SALTLICK CREE!.K.!8SALTL CK CREEK 9 !. OUTH FORK 21.! SALTLICK CREEK.!.!6SALTLICK CREEK 7 SOUTH FORK 9 Western !.! !. SOUTH FORK 1!..!2. Eastern Panhandle 8 POCATALICO RIVER 28 SOUTH FORK 1 6.!.! S UTH FORK 27 !. !.!..S!.O TH FORK 17 SO TH FORK 36 OUTH FORK 3.!5 Elk SOUTH FORK.!.! SOUTH FORK 33 BLAKES CREEK-ARMOUR CREEK 7 BIG DITCH 1 32 Elk 6 !. -

CBCP Final West Virginia Annex

CHESAPEAKE BAY COMPREHENSIVE WATER FINAL State of West RESOURCES AND Virginia Annex RESTORATION PLAN July 2019 This document was developed in coordination with multiple stakeholders, including the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the Chesapeake Bay Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, District of Columbia, States of Delaware, Maryland, New York and West Virginia, and Commonwealths of Pennsylvania and Virginia. This page intentionally left blank. State and District of Columbia Analyses CHESAPEAKE BAY COMPREHENSIVE WATER RESOURCES AND RESTORATION PLAN STATE CHAPTER State of West Virginia July 2019 This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents Section 1 ..................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.2 Water Stressors ......................................................................................................................................................... 1-3 Section 2 Restoration Efforts Contributing to Watershed Wide Priorities .......................... 2-1 2.1 Vitals Habitats Goal .................................................................................................................................................. 2-1 2.1.1 Outcome: Black Duck ................................................................................................................................ -

Fishing Guide

TROUT STOCKING Rivers and Streams Trout Stocking Code No. Stockings .........Period Code No. Stockings .........Period Code No. Stockings .........Period River or Stream: County Code: Area Q One .................... 1st week of March One ................................... February CR Varies .................................... Varies BW South Branch of the Potomac River: W-F: from 0.5 miles north of the Virginia line downstream (about 20 miles) to approximately One .....................................January M One each month .....February-May Pendleton (Franklin Section) 2 miles south of Upper Tract, near the old Poor Farm One every two weeks ..... March-May W Two................................... February MJ One each month ..... January-April South Branch of the Potomac River: One .....................................January Pendleton (Smoke Hole Section) W-F: from U.S. Route 220 bridge downstream to Big Bend Recreation Area One each week .............March-May BA Y One ...........................................April One ........................................ March One................................ The two weeks after Tilhance Creek: Berkeley BW: from one mile below Johnstown upstream 3 miles to state secondary Route 9/7 bridge X After April 1 or area is open to public F Columbus Day week Trout Run: Hardy W: from mouth at Wardensville upstream 7 miles Tuscarora Creek: Berkeley BW: from Martinsburg upstream 5 miles Trout Stocking River or Stream: County Waites Run: Hardy W: from state Route 55 bridge at Wardensville upstream 6.5 miles Code: Area Big Bullskin Run: Jefferson W: from near Wheatland 5 miles downstream to Kabletown Dillons Run: Hampshire BW: from state secondary Route 50/25 bridge upstream 4 miles Evitts Run: Jeferson W-F: from the Charles Town Park upstream to a point 0.5 miles west of town, along state Route 51 W-F: Lost City and Lost River bridges and downstream along state Route 259 to one mile above Lost River: Hardy the U.S. -

Water Quality Database Design and Data Dictionary

Water Quality Database Database Design and Data Dictionary Prepared For: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region III Chesapeake Bay Program Office January 2004 BACKGROUND...........................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................6 WATER QUALITY DATA.............................................................................................................................6 THE RELATIONAL CONCEPT ..................................................................................................................6 THE RELATIONAL DATABASE STRUCTURE ...................................................................................7 WATER QUALITY DATABASE STRUCTURE..........................................................8 PRIMARY TABLES ..........................................................................................................................................8 WQ_CRUISES ..................................................................................................................................................8 WQ_EVENT.......................................................................................................................................................8 WQ_DATA..........................................................................................................................................................9