Innovation Through Co-Opetition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments

Institute of Fisher Center for Business and Real Estate and Economic Research Urban Economics PROGRAM ON HOUSING AND URBAN POLICY DISSERTATION AND THESIS SERIES DISSERTATION NO. D07-001 ESSAYS ON EQUILIBRIUM ASSET PRICING AND INVESTMENTS By Jiro Yoshida Spring 2007 These papers are preliminary in nature: their purpose is to stimulate discussion and comment. Therefore, they are not to be cited or quoted in any publication without the express permission of the author. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida B.Eng. (The University of Tokyo) 1992 M.S. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) 1999 M.S. (University of California, Berkeley) 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor John Quigley, Chair Professor Dwight Ja¤ee Professor Richard Stanton Professor Adam Szeidl Spring 2007 The dissertation of Jiro Yoshida is approved: Chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments Copyright 2007 by Jiro Yoshida 1 Abstract Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration University of California, Berkeley Professor John Quigley, Chair Asset prices have tremendous impacts on economic decision-making. While substantial progress has been made in research on …nancial asset prices, we have a quite limited un- derstanding of the equilibrium prices of broader asset classes. This dissertation contributes to the understanding of properties of asset prices for broad asset classes, with particular attention on asset supply. -

Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science

Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Copyright © òýÔ Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. is is a special issue published in “Journal of Applied Mathematics.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Saeid Abbasbandy, Iran Song Cen, China Urmila Diwekar, USA Mina B. Abd-El-Malek, Egypt Tai-Ping Chang, Taiwan Vit Dolejsi, Czech Republic Mohamed A. Abdou, Egypt Shih-sen Chang, China BoQing Dong, China Subhas Abel, India Wei-Der Chang, Taiwan Rodrigo W. dos Santos, Brazil Janos Abonyi, Hungary Shuenn-Yih Chang, Taiwan Wenbin Dou, China Sergei Alexandrov, Russia Kripasindhu Chaudhuri, India Rafael Escarela-Perez, Mexico M. Montaz Ali, South Africa Yuming Chen, Canada Magdy A. Ezzat, Egypt Mohammad R, Aliha, Iran Jianbing Chen, China Meng Fan, China Carlos J. S. Alves, Portugal Xinkai Chen, Japan Ya Ping Fang, China Mohamad Alwash, USA Rushan Chen, China István Faragó, Hungary Gholam R. Amin, Oman Ke Chen, UK Didier Felbacq, France Igor Andrianov, Germany Zhang Chen, China Ricardo Femat, Mexico Boris Andrievsky, Russia Zhi-Zhong Chen, Japan Antonio J. M. Ferreira, Portugal Whye-Teong Ang, Singapore Ru-Dong Chen, China George Fikioris, Greece Abul-Fazal M. -

Coalitional Stochastic Stability in Games, Networks and Markets

Coalitional stochastic stability in games, networks and markets Ryoji Sawa∗ Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison November 24, 2011 Abstract This paper examines a dynamic process of unilateral and joint deviations of agents and the resulting stochastic evolution of social conventions in a class of interactions that includes normal form games, network formation games, and simple exchange economies. Over time agents unilater- ally and jointly revise their strategies based on the improvements that the new strategy profile offers them. In addition to the optimization process, there are persistent random shocks on agents utility that potentially lead to switching to suboptimal strategies. Under a logit specification of choice prob- abilities, we characterize the set of states that will be observed in the long-run as noise vanishes. We apply these results to examples including certain potential games and network formation games, as well as to the formation of free trade agreements across countries. Keywords: Logit-response dynamics; Coalitions; Stochastic stability; Network formation. JEL Classification Numbers: C72, C73. ∗Address: 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1393, United States., telephone: 1-608-262-0200, e-mail: [email protected]. The author is grateful to William Sandholm, Marzena Rostek and Marek Weretka for their advice and sugges- tions. The author also thanks seminar participants at University of Wisconsin-Madison for their comments and suggestions. 1 1 Introduction Our economic and social life is often conducted within a group of agents, such as people, firms or countries. For example, firms may form an R & D alliances and found a joint research venture rather than independently conducting R & D. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Stör, Lorenz Working Paper Conceptualizing power in the context of climate change: A multi-theoretical perspective on structure, agency & power relations VÖÖ Discussion Paper, No. 5/2017 Provided in Cooperation with: Vereinigung für Ökologische Ökonomie e.V. (VÖÖ), Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Stör, Lorenz (2017) : Conceptualizing power in the context of climate change: A multi-theoretical perspective on structure, agency & power relations, VÖÖ Discussion Paper, No. 5/2017, Vereinigung für Ökologische Ökonomie (VÖÖ), Heidelberg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/150540 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu VÖÖ Discussion Papers VÖÖ Discussion Papers · ISSN 2366-7753 No. -

Transferable Strategic Meta-Reasoning Models

TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS BY MICHAEL WUNDER Written under the direction of Matthew Stone New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS by MICHAEL WUNDER Dissertation Director: Matthew Stone How do strategic agents make decisions? For the first time, a confluence of advances in agent design, formation of massive online data sets of social behavior, and computational techniques have allowed for researchers to con- struct and learn much richer models than before. My central thesis is that, when agents engaged in repeated strategic interaction undertake a reasoning or learning process, the behavior resulting from this process can be charac- terized by two factors: depth of reasoning over base rules and time-horizon of planning. Values for these factors can be learned effectively from interac- tion and are transferable to new games, producing highly effective strategic responses. The dissertation formally presents a framework for addressing the problem of predicting a population’s behavior using a meta-reasoning model containing these strategic components. To evaluate this model, I explore sev- eral experimental case studies that show how to use the framework to predict ii and respond to behavior using observed data, covering settings ranging from a small number of computer agents to a larger number of human participants. iii Preface Captain Amazing: I knew you couldn’t change. Casanova Frankenstein: I knew you’d know that. Captain Amazing: Oh, I know that. AND I knew you’d know I’d know you knew. Casanova Frankenstein: But I didn’t. I only knew that you’d know that I knew. -

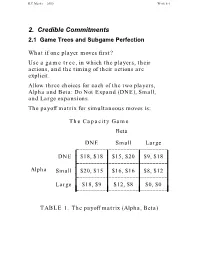

Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-1 2. Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection What if one player moves first? Use a game tree, in which the players, their actions, and the timing of their actions are explicit. Allow three choices for each of the two players, Alpha and Beta: Do Not Expand (DNE), Small, and Large expansions. The payoff matrix for simultaneous moves is: The Capacity Game Beta ________________________________DNE Small Large L L L L DNE $18, $18 $15, $20 $9, $18 _L_______________________________L L L L L L L Alpha SmallL $20, $15L $16, $16L $8, $12 L L________________________________L L L L L L L Large_L_______________________________ $18, $9L $12, $8L $0, $0 L TABLE 1. The payoff matrix (Alpha, Beta) R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-2 The game tree. If Alpha preempts Beta, by making its capacity decision before Beta does, then use the game tree: Alpha L S DNE Beta Beta Beta L S DNE L S DNE L S DNE 0 12 18 8 16 20 9 15 18 0 8 9 12 16 15 18 20 18 Figure 1. Game Tree, Payoffs: Alpha’s, Beta’s Use subgame perfect Nash equilibrium, in which each player chooses the best action for itself at each node it might reach, and assumes similar behaviour on the part of the other. R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-3 2.1.1 Backward Induction With complete information (all know what each has done), we can solve this by backward induction: 1. From the end (final payoffs), go up the tree to the first parent decision nodes. -

A Strategic Move for Long-Term Bridge Performance Within a Game Theory Framework by a Data-Driven Co-Active Mechanism

infrastructures Article A Strategic Move for Long-Term Bridge Performance within a Game Theory Framework by a Data-Driven Co-Active Mechanism O. Brian Oyegbile and Mi G. Chorzepa * College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 27 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) requires that states have less than 10% of the total deck area that is structurally deficient. It is a minimum risk benchmark for sustaining the National Highway System bridges. Yet, a decision-making framework is needed for obtaining the highest possible long-term return from investments on bridge maintenance, rehabilitation, and replacement (MRR). This study employs a data-driven coactive mechanism within a proposed game theory framework, which accounts for a strategic interaction between two players, the FHWA and a state Department of Transportation (DOT). The payoffs for the two players are quantified in terms of a change in service life. The proposed framework is used to investigate the element-level bridge inspection data from four US states (Georgia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York). By reallocating 0.5% (from 10% to 10.5%) of the deck resources to expansion joints and joint seals, both federal and state transportation agencies (e.g., FHWA and state DOTs in the U.S.) will be able to improve the overall bridge performance. This strategic move in turn improves the deck condition by means of a co-active mechanism and yields a higher payoff for both players. It is concluded that the proposed game theory framework with a strategic move, which leverages element interactions for MRR, is most effective in New York where the average bridge service life is extended by 15 years. -

Strategic Management

This page intentionally left blank Strategic Management CONCEPTS AND CASES Editorial Director: Sally Yagan Manager, Visual Research: Beth Brenzel Editor in Chief: Eric Svendsen Manager, Rights and Permissions: Zina Arabia Acquisitions Editor: Kim Norbuta Image Permission Coordinator: Cynthia Vincenti Product Development Manager: Ashley Santora Manager, Cover Visual Research & Permissions: Editorial Project Manager: Claudia Fernandes Karen Sanatar Editorial Assistant: Meg O’Rourke Cover Art: Vetta TM Collection Dollar Bin: Director of Marketing: Patrice Lumumba Jones istockphoto Marketing Manager: Nikki Ayana Jones Editorial Media Project Manager: Ashley Lulling Marketing Assistant: Ian Gold Production Media Project Manager: Lisa Rinaldi Senior Managing Editor: Judy Leale Full-Service Project Management: Thistle Hill Associate Production Project Manager: Publishing Services, LLC Ana Jankowski Composition: Integra Software Services, Ltd. Operations Specialist: Ilene Kahn Printer/Binder: Courier/Kendallville Art Director: Steve Frim Cover Printer: Lehigh-Phoenix Color/Hagerstown Text and Cover Designer: Judy Allan Text Font: 10/12 Times Credits and acknowledgments borrowed from other sources and reproduced, with permission, in this textbook appear on appropriate page within text. Copyright © 2011, 2009, 2007 by Pearson Education, Inc., publishing as Prentice Hall, One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. This publication is protected by Copyright, and permission should be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or likewise. To obtain permission(s) to use material from this work, please submit a written request to Pearson Education, Inc., Permissions Department, One Lake Street, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458. -

Organization and Management of Coopetition - Trust the Competition, Not the Competitor

Organization and Management of Coopetition - Trust the Competition, Not the Competitor Master’s Thesis 30 credits Department of Business Studies Uppsala University Spring Semester of 2015 Date of Submission: 2015-05-29 Jessica Winberg Hedvig Öster Supervisor: Katarina Hamberg Lagerström ABSTRACT In the search for innovation, high technology firms in the same industries turn to each other for R&D collaborations. The collaboration form where competitors cooperate have been defined as “coopetition” and the term builds on the interplay between competitive and cooperative forces. While coopetition brings benefits such as shared risks and costs, it implies organizational and managerial challenges as two opposing logics merge. This complexity calls for a deeper understanding of how firms organize and manage coopetition and why they organization and manage coopetition in the way they do. This thesis is set to answer these questions by empirically investigate coopetition at a case firm active in a high technology context with a long experience of collaborating with competitors. By acknowledging coopetition as a phenomenon carried out in the shape of projects, the internal organization and management could been thoroughly understood as project management allows a more detailed view of coopetition. Key findings concludes that in this empirical context, finance is the prior reason for engaging in coopetition, competitive forces are superior to cooperative forces in coopetition projects and that coopetition influence innovation more through contributing with funding than by an exchange of knowledge between competitors. All these aspects are further stated to impact organization and management of coopetition. Key Words: Coopetition, Competition, Cooperation, Organization, Management, High Technology Industry, Innovation, Project Management 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT When two best friends that already spends all waking time in each other’s company, decides to write a master thesis together, some may say it is bound for a catastrophe. -

Coopetition As a Business Strategy That Changes the Market Structures

SILESIAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY PUBLISHING HOUSE SCIENTIFIC PAPERS OF SILESIAN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY 2021 ORGANIZATION AND MANAGEMENT SERIES NO. 151 1 COOPETITION AS A BUSINESS STRATEGY THAT CHANGES 2 THE MARKET STRUCTURES: THE CASE OF LONG-DISTANCE 3 PASSENGER TRANSPORT MARKETS IN POLAND 4 Andrzej PESTKOWSKI 5 Wrocław University of Economics and Business, Faculty of Management, Computer Science and Finance; 6 [email protected], ORCID: 0000-0002-5778-8420 7 Purpose: This paper concerns the phenomenon of two-way causality effect between market 8 structures and coopetition occurrence. It is assumed that certain characteristics of an existing 9 market structure implicate the decision to deploy the strategy of coopetition by companies. 10 Moreover, the opposite effect might be expected, that is coopetition between market rivals 11 changes the market structure on which it was implemented in the first place. In the paper various 12 aspects and approaches of the abovementioned phenomena have been considered. 13 Design/methodology/approach: The author investigates the events, motives and values that 14 lead companies to deploy the coopetition strategy. Furthermore, the theoretical and conceptual 15 bases for the effect of the coopetition impacting the change of market structures have been 16 provided. A wide analysis of managers’ decision resulting from the occurrence of certain 17 strategic events has been conducted with the use of comparison matrixes. Finally, in the last 18 part of the study the author’s empirical research on two passenger transport relevant markets 19 has been presented. 20 Findings: Certain market strategies characteristics affected companies to deploy the 21 coopetition strategy and the other way round, the strategy changed the market structure in the 22 result of competitors’ decision. -

Biform Games∗

Biform Games∗ Adam Brandenburger Harborne Stuart Stern School of Business Graduate School of Business New York University Columbia University 44 West Fourth Street 3022 Broadway New York, NY 10012 New York, NY 10027 [email protected] [email protected] www.stern.nyu.edu/ abranden www.columbia.edu/ hws7 ∼ ∼ Current Version: February 2006 Forthcoming in Management Science Abstract Both noncooperative and cooperative game theory have been applied to business strategy. We propose a hybrid noncooperative-cooperative game model, which we call a biform game. This is designed to formalize the notion of business strategy as making moves to try to shape the competitive environment in a favorable way. (The noncooperative component of a biform game models the strategic moves. The cooperative component models the resulting competitive environment.) We give biform models of various well-known business strategies. We prove general results on when a business strategy, modelled as a biform game, will be efficient. ∗Bob Aumann, Pierpaolo Battigalli, David Collis, Karen Feng, Amanda Friedenberg, Rena Henderson, John Hillas, Jerry Keisler, Vijay Krishna, Andreu Mas-Colell, Barry Nalebuff, John Sutton, and many participants at seminar presentations of this work provided important input. We are especially indebted to Louis Makowski and Joe Ostroy for extensive discussions, and to Ken Corts and Elon Kohlberg for several valuable observations. The associate editor and referees made very helpful comments and suggestions. Financial support from Columbia Business School, Harvard Business School, and the Stern School of Business is gratefully acknowledged. bg-02-24-06 1 Introduction There have been a number of applications of game theory to the field of business strategy in recent years. -

Thucydides on Nash.Pdf

2 THUCYDIDES ON NASH VS. STACKELBERG: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SEQUENCE OF MOVES IN GAMES The paper provides a general characterization of the conditions in two-by-two games under which players will prefer to move first or second, or will be indifferent to the sequence of moves. The general result is that in games without a pure strategy equilibrium either there will be a struggle for the second move, or the players will agree on the sequence of play; a struggle for the first move is characteristic of games with two pure strategy equilibria; in games with one pure strategy equilibrium, players most of the time will be indifferent about the sequence of moves. Examples from Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War and other political and social situations illustrate how players manage to change the sequence of moves. 3 THUCYDIDES ON NASH VS. STACKELBERG: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SEQUENCE OF MOVES IN GAMES In a period of "new institutionalism" in political science, one hardly has to argue about the importance of institutions. It is widely accepted that institutions shape political outcomes. Although now, after the behavioral revolution, the study of political institutions has re-entered the field of political science, in very few cases are we able to provide a theoretical understanding of the general properties of certain rules. The most frequently studied institutions are of course those of majority rule,2 but this rule is most of the time embedded in a much more rich institutional framework, 3 about which we know very few propositions of general applicability—for example, that a close rule restricts the set of possible outcomes compared to an open rule, that exclusive jurisdictions of committees restrict outcomes even further, or that strategic voting leads to an outcome belonging to the top cycle.6 This paper provides a characterization of one important rule: the sequence in which two players play a game.