Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments

Institute of Fisher Center for Business and Real Estate and Economic Research Urban Economics PROGRAM ON HOUSING AND URBAN POLICY DISSERTATION AND THESIS SERIES DISSERTATION NO. D07-001 ESSAYS ON EQUILIBRIUM ASSET PRICING AND INVESTMENTS By Jiro Yoshida Spring 2007 These papers are preliminary in nature: their purpose is to stimulate discussion and comment. Therefore, they are not to be cited or quoted in any publication without the express permission of the author. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida B.Eng. (The University of Tokyo) 1992 M.S. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) 1999 M.S. (University of California, Berkeley) 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor John Quigley, Chair Professor Dwight Ja¤ee Professor Richard Stanton Professor Adam Szeidl Spring 2007 The dissertation of Jiro Yoshida is approved: Chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments Copyright 2007 by Jiro Yoshida 1 Abstract Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration University of California, Berkeley Professor John Quigley, Chair Asset prices have tremendous impacts on economic decision-making. While substantial progress has been made in research on …nancial asset prices, we have a quite limited un- derstanding of the equilibrium prices of broader asset classes. This dissertation contributes to the understanding of properties of asset prices for broad asset classes, with particular attention on asset supply. -

Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science

Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Copyright © òýÔ Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. is is a special issue published in “Journal of Applied Mathematics.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Saeid Abbasbandy, Iran Song Cen, China Urmila Diwekar, USA Mina B. Abd-El-Malek, Egypt Tai-Ping Chang, Taiwan Vit Dolejsi, Czech Republic Mohamed A. Abdou, Egypt Shih-sen Chang, China BoQing Dong, China Subhas Abel, India Wei-Der Chang, Taiwan Rodrigo W. dos Santos, Brazil Janos Abonyi, Hungary Shuenn-Yih Chang, Taiwan Wenbin Dou, China Sergei Alexandrov, Russia Kripasindhu Chaudhuri, India Rafael Escarela-Perez, Mexico M. Montaz Ali, South Africa Yuming Chen, Canada Magdy A. Ezzat, Egypt Mohammad R, Aliha, Iran Jianbing Chen, China Meng Fan, China Carlos J. S. Alves, Portugal Xinkai Chen, Japan Ya Ping Fang, China Mohamad Alwash, USA Rushan Chen, China István Faragó, Hungary Gholam R. Amin, Oman Ke Chen, UK Didier Felbacq, France Igor Andrianov, Germany Zhang Chen, China Ricardo Femat, Mexico Boris Andrievsky, Russia Zhi-Zhong Chen, Japan Antonio J. M. Ferreira, Portugal Whye-Teong Ang, Singapore Ru-Dong Chen, China George Fikioris, Greece Abul-Fazal M. -

Coalitional Stochastic Stability in Games, Networks and Markets

Coalitional stochastic stability in games, networks and markets Ryoji Sawa∗ Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison November 24, 2011 Abstract This paper examines a dynamic process of unilateral and joint deviations of agents and the resulting stochastic evolution of social conventions in a class of interactions that includes normal form games, network formation games, and simple exchange economies. Over time agents unilater- ally and jointly revise their strategies based on the improvements that the new strategy profile offers them. In addition to the optimization process, there are persistent random shocks on agents utility that potentially lead to switching to suboptimal strategies. Under a logit specification of choice prob- abilities, we characterize the set of states that will be observed in the long-run as noise vanishes. We apply these results to examples including certain potential games and network formation games, as well as to the formation of free trade agreements across countries. Keywords: Logit-response dynamics; Coalitions; Stochastic stability; Network formation. JEL Classification Numbers: C72, C73. ∗Address: 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1393, United States., telephone: 1-608-262-0200, e-mail: [email protected]. The author is grateful to William Sandholm, Marzena Rostek and Marek Weretka for their advice and sugges- tions. The author also thanks seminar participants at University of Wisconsin-Madison for their comments and suggestions. 1 1 Introduction Our economic and social life is often conducted within a group of agents, such as people, firms or countries. For example, firms may form an R & D alliances and found a joint research venture rather than independently conducting R & D. -

Structure and Agency: an Analysis of the Impact of Structure on Group Agents Elizabeth Kaye Victor University of South Florida, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Scholar Commons | University of South Florida Research University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Structure and Agency: An Analysis of the Impact of Structure on Group Agents Elizabeth Kaye Victor University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Victor, Elizabeth Kaye, "Structure and Agency: An Analysis of the Impact of Structure on Group Agents" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4246 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Structure and Agency: An Analysis of the Impact of Structure on Group Agents by Elizabeth Kaye Victor A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Rebecca Kukla, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Stephen Turner, Ph.D. Colin Heydt, Ph.D. Bryce Hueber, Ph.D Douglas Jesseph, Ph.D. Walter Nord, Ph.D. Date of Approval: May 16, 2012 Keywords: Group Agency, Business Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility, Ethics, Human Resource Management Copyright © 2012, Elizabeth Kaye Victor Dedication I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my father and friend, Joe. -

Social Science As Reading and Performance: a Cultural-Sociological Understanding of Epistemology

European Journal of Social Theory http://est.sagepub.com Social Science as Reading and Performance: A Cultural-Sociological Understanding of Epistemology Isaac Reed and Jeffrey Alexander European Journal of Social Theory 2009; 12; 21 DOI: 10.1177/1368431008099648 The online version of this article can be found at: http://est.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/12/1/21 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for European Journal of Social Theory can be found at: Email Alerts: http://est.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://est.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://est.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/12/1/21 Downloaded from http://est.sagepub.com at YALE UNIV LIBRARY on June 19, 2009 European Journal of Social Theory 12(1): 21–41 Copyright © 2009 Sage Publications: Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC Social Science as Reading and Performance A Cultural-Sociological Understanding of Epistemology Isaac Reed and Jeffrey Alexander UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO AT BOULDER AND YALE UNIVERSITY, USA Abstract In the age of the ‘return to the empirical’ in which the theoretical disputes of an earlier era seem to have fallen silent, we seek to excavate the intel- lectual conditions for reviving theoretical debate, for it is upon this recovery that deeper understanding of the nature and purpose of empirical social science depends. We argue against the all too frequent turn to ontology, whereby critical realists have sought an epistemological guarantor of socio- logical validity. We seek, to the contrary, to crystallize a culturally-based, hermeneutic account of a rational social science. -

Ontology and Epistemology in Political Science

Chapter 1 A Skin, not a Sweater: Ontology and Epistemology in Political Science DAVID MARSH AND PAUL FURLONG This chapter introduces the reader to the key issues that underpin what we do as social or political scientists. Each social scientist's orientation to their subject is shaped by their ontological and epistemological position. Most often those positions are implicit rather than explicit, but, regardless of whether they are acknowledged, they shape the approach to theory and the methods which the social scientist utilises. At first these issues seem difficult but our major point is that they are not issues that can be avoided (for a similar view see Blyth, Chapter 14). They are like a skin not a sweater: they cannot be put on and taken off whenever the researcher sees fit. In our view, all students of political science should recognise and acknowledge their own ontological and epistemological positions and be able to defend these positions against critiques from other positions. This means they need to understand the alternative positions on these fundamental questions. As such, this chapter has two key aims. First, we will introduce these ontological and epistemological questions in as accessible a way as possible in order to allow the reader who is new to these issues to reflect on their own position. Second, this introduction is crucial to the readers of this book because the authors of the subsequent chapters address these issues and they inform the subject matter of their chapters. As such, this basic introduction is also essential for readers who want fully to appreciate the substantive content of this book. -

Structuration Theory Amid Negative and Positive Criticism

Structuration theory amid negative and positive criticism Wafa Kort Ligue laboratory Assistant at ISG Tunis E-mail : [email protected] Jamel Eddine Gharbi Ligue laboratory Lecturer at FSEG Jendouba E-mail : [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper tries to sum up the criticism that turns around structuration theory to help the applications in MIS field. The literature review allow to advance three categories of criticisms: (1) the conflation of structure and human agent, (2) the complexity and the outspread of the theory that lead to contradictions, and (3) the lack of assumptions and methodological guidelines. Some recommendations are given to direct future researches. Key words: Structures, Agency, Duality of structural, Time-space dimension. Introduction Structuration theory is more and more used in the field of management information system. In fact, it offers the possibility to conceptualize IT artifact in a dynamic way and goes beyond the deterministic conceptualization in previous studies. The concept of the duality of structure is the main concept in structuration theory. It means that structural properties are at the same time the result and medium of practices which are organized in a recursive way. It allows a new perspective of the relationship between technology and user. Hence, the use of structuration theory in the IS field aims to provide a theoretical approach that helps the understanding of the interaction between user and information technology, the implications of these interactions, and the way to control their consequences (Pozzebon and Pinsonneault, 2005). More specifically, structuration theory allows human agency to surface and gives them the power to explain the difference of outcome in presence of technology (Boudreau and Robey, 2005). -

Transferable Strategic Meta-Reasoning Models

TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS BY MICHAEL WUNDER Written under the direction of Matthew Stone New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS by MICHAEL WUNDER Dissertation Director: Matthew Stone How do strategic agents make decisions? For the first time, a confluence of advances in agent design, formation of massive online data sets of social behavior, and computational techniques have allowed for researchers to con- struct and learn much richer models than before. My central thesis is that, when agents engaged in repeated strategic interaction undertake a reasoning or learning process, the behavior resulting from this process can be charac- terized by two factors: depth of reasoning over base rules and time-horizon of planning. Values for these factors can be learned effectively from interac- tion and are transferable to new games, producing highly effective strategic responses. The dissertation formally presents a framework for addressing the problem of predicting a population’s behavior using a meta-reasoning model containing these strategic components. To evaluate this model, I explore sev- eral experimental case studies that show how to use the framework to predict ii and respond to behavior using observed data, covering settings ranging from a small number of computer agents to a larger number of human participants. iii Preface Captain Amazing: I knew you couldn’t change. Casanova Frankenstein: I knew you’d know that. Captain Amazing: Oh, I know that. AND I knew you’d know I’d know you knew. Casanova Frankenstein: But I didn’t. I only knew that you’d know that I knew. -

Nobody to Shoot? Power, Structure, and Agency: a Dialogue. Journal

This article was downloaded by: On: 30 January 2009 Access details: Access Details: Free Access Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Power Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t778749998 Nobody to shoot? Power, structure, and agency: A dialogue Clarissa Hayward a; Steven Lukes b a Washington University in Saint Louis, Political Science, b New York University, Sociology, Online Publication Date: 01 April 2008 To cite this Article Hayward, Clarissa and Lukes, Steven(2008)'Nobody to shoot? Power, structure, and agency: A dialogue',Journal of Power,1:1,5 — 20 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/17540290801943364 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17540290801943364 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

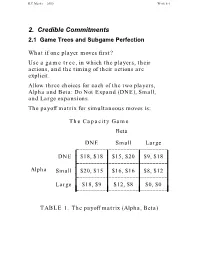

Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-1 2. Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection What if one player moves first? Use a game tree, in which the players, their actions, and the timing of their actions are explicit. Allow three choices for each of the two players, Alpha and Beta: Do Not Expand (DNE), Small, and Large expansions. The payoff matrix for simultaneous moves is: The Capacity Game Beta ________________________________DNE Small Large L L L L DNE $18, $18 $15, $20 $9, $18 _L_______________________________L L L L L L L Alpha SmallL $20, $15L $16, $16L $8, $12 L L________________________________L L L L L L L Large_L_______________________________ $18, $9L $12, $8L $0, $0 L TABLE 1. The payoff matrix (Alpha, Beta) R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-2 The game tree. If Alpha preempts Beta, by making its capacity decision before Beta does, then use the game tree: Alpha L S DNE Beta Beta Beta L S DNE L S DNE L S DNE 0 12 18 8 16 20 9 15 18 0 8 9 12 16 15 18 20 18 Figure 1. Game Tree, Payoffs: Alpha’s, Beta’s Use subgame perfect Nash equilibrium, in which each player chooses the best action for itself at each node it might reach, and assumes similar behaviour on the part of the other. R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-3 2.1.1 Backward Induction With complete information (all know what each has done), we can solve this by backward induction: 1. From the end (final payoffs), go up the tree to the first parent decision nodes. -

A Strategic Move for Long-Term Bridge Performance Within a Game Theory Framework by a Data-Driven Co-Active Mechanism

infrastructures Article A Strategic Move for Long-Term Bridge Performance within a Game Theory Framework by a Data-Driven Co-Active Mechanism O. Brian Oyegbile and Mi G. Chorzepa * College of Engineering, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 July 2020; Accepted: 27 September 2020; Published: 29 September 2020 Abstract: The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) requires that states have less than 10% of the total deck area that is structurally deficient. It is a minimum risk benchmark for sustaining the National Highway System bridges. Yet, a decision-making framework is needed for obtaining the highest possible long-term return from investments on bridge maintenance, rehabilitation, and replacement (MRR). This study employs a data-driven coactive mechanism within a proposed game theory framework, which accounts for a strategic interaction between two players, the FHWA and a state Department of Transportation (DOT). The payoffs for the two players are quantified in terms of a change in service life. The proposed framework is used to investigate the element-level bridge inspection data from four US states (Georgia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York). By reallocating 0.5% (from 10% to 10.5%) of the deck resources to expansion joints and joint seals, both federal and state transportation agencies (e.g., FHWA and state DOTs in the U.S.) will be able to improve the overall bridge performance. This strategic move in turn improves the deck condition by means of a co-active mechanism and yields a higher payoff for both players. It is concluded that the proposed game theory framework with a strategic move, which leverages element interactions for MRR, is most effective in New York where the average bridge service life is extended by 15 years. -

A Critical Imaginal Hermeneutics Approach to Explore Unconscious Influences on Professional Practices: a Ricoeur and Jung Partnership

The Qualitative Report Volume 25 Number 10 Article 3 10-3-2020 A Critical Imaginal Hermeneutics Approach to Explore Unconscious Influences on Professional Practices: A Ricoeur and Jung Partnership Rosa Bologna The Academy of Art & Play Therapy, [email protected] Franziska Trede University of Technology Sydney, [email protected] Narelle Patton Charles Sturt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Child Psychology Commons, Counseling Psychology Commons, Counselor Education Commons, Other Sociology Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended APA Citation Bologna, R., Trede, F., & Patton, N. (2020). A Critical Imaginal Hermeneutics Approach to Explore Unconscious Influences on Professional Practices: A Ricoeur and Jung Partnership. The Qualitative Report, 25(10), 3486-3518. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2020.4185 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Critical Imaginal Hermeneutics Approach to Explore Unconscious Influences on Professional Practices: A Ricoeur and Jung Partnership Abstract Professional relationships are at the heart of professional practice. Qualitative studies exploring professional practice relationships are typically positioned in either the social constructivist (interpretive) paradigm where the aim is to explore actors’ subjective understandings of their relationships and relational practices, or in the critical paradigm where the aim is to reveal objective unconscious structures and hidden power plays influencing actors’ practices.