CHAPTER 13: Strategic Decision Making in Oligopoly Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments

Institute of Fisher Center for Business and Real Estate and Economic Research Urban Economics PROGRAM ON HOUSING AND URBAN POLICY DISSERTATION AND THESIS SERIES DISSERTATION NO. D07-001 ESSAYS ON EQUILIBRIUM ASSET PRICING AND INVESTMENTS By Jiro Yoshida Spring 2007 These papers are preliminary in nature: their purpose is to stimulate discussion and comment. Therefore, they are not to be cited or quoted in any publication without the express permission of the author. UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida B.Eng. (The University of Tokyo) 1992 M.S. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) 1999 M.S. (University of California, Berkeley) 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor John Quigley, Chair Professor Dwight Ja¤ee Professor Richard Stanton Professor Adam Szeidl Spring 2007 The dissertation of Jiro Yoshida is approved: Chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments Copyright 2007 by Jiro Yoshida 1 Abstract Essays on Equilibrium Asset Pricing and Investments by Jiro Yoshida Doctor of Philosophy in Business Administration University of California, Berkeley Professor John Quigley, Chair Asset prices have tremendous impacts on economic decision-making. While substantial progress has been made in research on …nancial asset prices, we have a quite limited un- derstanding of the equilibrium prices of broader asset classes. This dissertation contributes to the understanding of properties of asset prices for broad asset classes, with particular attention on asset supply. -

California Institute of Technology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Caltech Authors - Main DIVISION OF THE HUM ANITIES AND SO CI AL SCIENCES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY PASADENA, CALIFORNIA 91125 IMPLEMENTATION THEORY Thomas R. Palfrey � < a: 0 1891 u. "')/,.. () SOCIAL SCIENCE WORKING PAPER 912 September 1995 Implementation Theory Thomas R. Palfrey Abstract This surveys the branch of implementation theory initiated by Maskin (1977). Results for both complete and incomplete information environments are covered. JEL classification numbers: 025, 026 Key words: Implementation Theory, Mechanism Design, Game Theory, Social Choice Implementation Theory* Thomas R. Palfrey 1 Introduction Implementation theory is an area of research in economic theory that rigorously investi gates the correspondence between normative goals and institutions designed to achieve {implement) those goals. More precisely, given a normative goal or welfare criterion for a particular class of allocation pro blems (or domain of environments) it formally char acterizes organizational mechanisms that will guarantee outcomes consistent with that goal, assuming the outcomes of any such mechanism arise from some specification of equilibrium behavior. The approaches to this problem to date lie in the general domain of game theory because, as a matter of definition in the implementation theory litera ture, an institution is modelled as a mechanism, which is essentially a non-cooperative game. Moreover, the specific models of equilibrium behavior -

Can Game Theory Be Used to Address PPP Renegotiations?

Can game theory be used to address PPP renegotiations? A retrospective study of the of the Metronet - London Underground PPP By Gregory Michael Kennedy [152111301] Supervisors Professor Ricardo Ferreira Reis, PhD Professor Joaquim Miranda Sarmento, PhD Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of MSc in Business Administration, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa June 2013 Abstract of thesis entitled “Can game theory be used to address PPP renegotiations? A retrospective study of the of the Metronet - London Underground PPP” Submitted by Gregory Michael Kennedy (152111301) In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of MSc in Business Administration, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa June 2013 Public Private Partnerships (PPPs) have been introduced in many countries in order to increase the supply of public infrastructure services. The main criterion for implementing a PPP is that it will provide value for money. Often, however, these projects enter into financial distress which requires that they either be rescued or retendered. The cost of such a financial renegotiation can erode the value for money supposed to be created by the PPP. Due to the scale and complexity of these projects, the decision either to rescue or retender the project is not straightforward. We determine whether game theory can aid the decision making process in PPP renegotiation by applying a game theory model retrospectively to the failure of the Metronet - London Underground PPP. We study whether the model can be applied to a real PPP case, whether the application of this model would have changed the outcome of the case and, finally, whether and how the model can be used in future PPP renegotiations. -

Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science

Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Journal of Applied Mathematics Experimental Game Theory and Its Application in Sociology and Political Science Guest Editors: Arthur Schram, Vincent Buskens, Klarita Gërxhani, and Jens Großer Copyright © òýÔ Hindawi Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved. is is a special issue published in “Journal of Applied Mathematics.” All articles are open access articles distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Editorial Board Saeid Abbasbandy, Iran Song Cen, China Urmila Diwekar, USA Mina B. Abd-El-Malek, Egypt Tai-Ping Chang, Taiwan Vit Dolejsi, Czech Republic Mohamed A. Abdou, Egypt Shih-sen Chang, China BoQing Dong, China Subhas Abel, India Wei-Der Chang, Taiwan Rodrigo W. dos Santos, Brazil Janos Abonyi, Hungary Shuenn-Yih Chang, Taiwan Wenbin Dou, China Sergei Alexandrov, Russia Kripasindhu Chaudhuri, India Rafael Escarela-Perez, Mexico M. Montaz Ali, South Africa Yuming Chen, Canada Magdy A. Ezzat, Egypt Mohammad R, Aliha, Iran Jianbing Chen, China Meng Fan, China Carlos J. S. Alves, Portugal Xinkai Chen, Japan Ya Ping Fang, China Mohamad Alwash, USA Rushan Chen, China István Faragó, Hungary Gholam R. Amin, Oman Ke Chen, UK Didier Felbacq, France Igor Andrianov, Germany Zhang Chen, China Ricardo Femat, Mexico Boris Andrievsky, Russia Zhi-Zhong Chen, Japan Antonio J. M. Ferreira, Portugal Whye-Teong Ang, Singapore Ru-Dong Chen, China George Fikioris, Greece Abul-Fazal M. -

Coalitional Stochastic Stability in Games, Networks and Markets

Coalitional stochastic stability in games, networks and markets Ryoji Sawa∗ Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison November 24, 2011 Abstract This paper examines a dynamic process of unilateral and joint deviations of agents and the resulting stochastic evolution of social conventions in a class of interactions that includes normal form games, network formation games, and simple exchange economies. Over time agents unilater- ally and jointly revise their strategies based on the improvements that the new strategy profile offers them. In addition to the optimization process, there are persistent random shocks on agents utility that potentially lead to switching to suboptimal strategies. Under a logit specification of choice prob- abilities, we characterize the set of states that will be observed in the long-run as noise vanishes. We apply these results to examples including certain potential games and network formation games, as well as to the formation of free trade agreements across countries. Keywords: Logit-response dynamics; Coalitions; Stochastic stability; Network formation. JEL Classification Numbers: C72, C73. ∗Address: 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1393, United States., telephone: 1-608-262-0200, e-mail: [email protected]. The author is grateful to William Sandholm, Marzena Rostek and Marek Weretka for their advice and sugges- tions. The author also thanks seminar participants at University of Wisconsin-Madison for their comments and suggestions. 1 1 Introduction Our economic and social life is often conducted within a group of agents, such as people, firms or countries. For example, firms may form an R & D alliances and found a joint research venture rather than independently conducting R & D. -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Stör, Lorenz Working Paper Conceptualizing power in the context of climate change: A multi-theoretical perspective on structure, agency & power relations VÖÖ Discussion Paper, No. 5/2017 Provided in Cooperation with: Vereinigung für Ökologische Ökonomie e.V. (VÖÖ), Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Stör, Lorenz (2017) : Conceptualizing power in the context of climate change: A multi-theoretical perspective on structure, agency & power relations, VÖÖ Discussion Paper, No. 5/2017, Vereinigung für Ökologische Ökonomie (VÖÖ), Heidelberg This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/150540 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ www.econstor.eu VÖÖ Discussion Papers VÖÖ Discussion Papers · ISSN 2366-7753 No. -

Download Article

© October 2017 | IJIRT | Volume 4 Issue 5 | ISSN: 2349-6002 The Analogous Application of Game Theory and Monte Carlo Simulation Techniques from World War II to Business Decision Making Dhriti Malviya1, Disha Gupta2, Hiya Banerjee3, Dhairya Shah4, Eashan Shetty5 1, 2,3,4,5 Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies, Mumbai, India Abstract- The Second World War, one of the most ‗Operations Research‘ only came up in the year 1940. gruelling events in the history of mankind, also marks During World War II, a team of humans referred to the emergence of one of modern-day’s most widely used as the Blackett‘s Circus in UK first applied scientific scientific disciplines – Operations Research (OR). techniques to analyze military operations to win the Rather than defining OR as a ‘part of mathematics’, a war and thus developed the scientific discipline – better characterization of the sequence of events would be that some mathematicians during World War II Operations Research. Operations Research includes were coerced into mixed disciplinary units dominated plenty of problem-solving techniques like by physicists and statisticians, and directed to mathematical models, statistics and algorithms to participate in an assorted mix of activities which were assist in decision-making. OR is used to analyze clubbed together under the rubric of ‘Operations advanced real-world systems, typically with the Research’. Some of these activities ranged from target of improving or optimizing the tasks. curating a solution for the neutron scattering problem The aim during WWII was to get utmost economical in atomic bomb design to strategizing military attacks usage of restricted military resources by the by means of choosing the best possible route to travel. -

1 Heuristics, Thinking About Others, and Strategic

Heuristics, thinking about others, and strategic management: Insights from behavioral game theory Davide Marchiori University of Southern Denmark Rosemarie Nagel ICREA, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, BGSE Jens Schmidt Aalto University Abstract The outcome of strategic decisions (such as market entry or technology adoption) depends on the decisions made by others (such as competitors, customers, or suppliers). To anticipate others’ decisions managers must form beliefs about them and consider that others also form such higher-order beliefs. In this paper we draw on insights from behavioral game theory —in particular the level-k model of higher-order reasoning— to introduce a two-part heuristic model of behavior in interactive decision situations. In the first part the decision maker constructs a simplified model of the situation as a game. As a toolbox for such formulations, we provide a classification of games that relies on both game-theoretic and behavioral dimensions. Our classification includes aggregative games in an extended Keynesian beauty contest formulation and two-person 2x2 games as their most simplified instances. In the second part we construct a two-step heuristic model of anchoring and adjustment based on the level-k model, which is a behaviorally plausible model of behavior in interactive decision situations. A key contribution of our article is to show how higher-order reasoning matters differently in different classes of games. We discuss implications of our arguments for strategy research and suggest opportunities for further study. Keywords: Behavioral game theory, beauty contest games, bounded rationality, heuristics in strategic Interaction, strategy, level k model, anchors. 1 1. Introduction “To change the metaphor slightly, professional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; [. -

The Mondee Gills Game (MGG) Were Always the Same, Although the Scenery Changed with Time

Mathematical Entertainments Michael Kleber and Ravi Vakil, Editors The Mondee Gills To switch or not to switch, that is the question ... game played in Mondee Gills is not so familiar because of the isolation of the country and pecu- Game AA liarities of the dialect of the Mondees. Many people confuse the game with its rogue variant sometimes played SASHA GNEDIN for money with thimbleriggers on the streets of big cities. Mainland historians trace the roots to primitive contests such as coin tossing and matching pennies. However, every Mondee knows that the game is as old as their land, and the land is really old. An ancient tomb unearthed by archaeol- This column is a place for those bits of contagious ogists on the western side of Capra Heuvel, the second- mathematics that travel from person to person in the highest hill in the country, was found to contain the remains of domesticated cave goats and knucklebones, which community, because they are so elegant, surprising, supports the hypothesis that the basics of the game go back to farmers of the late Neolithic Revolution. or appealing that one has an urge to pass them on. The rules of the Mondee Gills Game (MGG) were always the same, although the scenery changed with time. Nowa- Contributions are most welcome. days the Mondee Gills Monday TV broadcasts the game as an open-air reality show in which there are three caves, one goat, and two traditional characters called Monte and Con- nie. The goat is hidden by Monte in one of the caves before the show starts, two other caves are left empty. -

Transferable Strategic Meta-Reasoning Models

TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS BY MICHAEL WUNDER Written under the direction of Matthew Stone New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION TRANSFERABLE STRATEGIC META-REASONING MODELS by MICHAEL WUNDER Dissertation Director: Matthew Stone How do strategic agents make decisions? For the first time, a confluence of advances in agent design, formation of massive online data sets of social behavior, and computational techniques have allowed for researchers to con- struct and learn much richer models than before. My central thesis is that, when agents engaged in repeated strategic interaction undertake a reasoning or learning process, the behavior resulting from this process can be charac- terized by two factors: depth of reasoning over base rules and time-horizon of planning. Values for these factors can be learned effectively from interac- tion and are transferable to new games, producing highly effective strategic responses. The dissertation formally presents a framework for addressing the problem of predicting a population’s behavior using a meta-reasoning model containing these strategic components. To evaluate this model, I explore sev- eral experimental case studies that show how to use the framework to predict ii and respond to behavior using observed data, covering settings ranging from a small number of computer agents to a larger number of human participants. iii Preface Captain Amazing: I knew you couldn’t change. Casanova Frankenstein: I knew you’d know that. Captain Amazing: Oh, I know that. AND I knew you’d know I’d know you knew. Casanova Frankenstein: But I didn’t. I only knew that you’d know that I knew. -

M9302 Mathematical Models in Economics

M9302 Mathematical Models in Economics Game Theory – Brief Introduction The work on this text has been supported by the project CZ.1.07/2.2.00/15.0203. What is Game Theory? We do not live in vacuum. Whether we like it or not, all of us are strategists. ST is art but its foundations consist of some simple basic principles. The science of strategic thinking is called Game Theory. Where is Game Theory coming from? Game Theory was created by Von Neumann and Morgenstern (1944) in their classic book The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior Two distinct approaches to the theory of games: 1. Strategic/Non-cooperative Approach 2. Coalition/Cooperative Approach Where is Game Theory coming from? The key contributions of John Nash: 1. The notion of Nash equilibrium 2. Arguments for determining the two-person bargaining problems Other significant names: N-Nash, A-Aumann, S-Shapley&Selten, H- Harsanyi Lecture 1 26.02.2010 M9302 Mathematical Models in Economics 1.1.Static Games of Complete Information Instructor: Georgi Burlakov The static (simultaneous-move) games Informally, the games of this class could be described as follows: First, players simultaneously choose a move (action). Then, based on the resulting combination of actions chosen in total, each player receives a given payoff. Example: Students’ Dilemma Strategic behaviour of students taking a course: First, each of you is forced to choose between studying HARD or taking it EASY. Then, you do your exam and get a GRADE. Static Games of Complete Information Standard assumptions: Players move (take an action or make a choice) simultaneously at a moment – it is STATIC Each player knows what her payoff and the payoff of the other players will be at any combination of chosen actions – it is COMPLETE INFORMATION Example: Students’ Dilemma Standard assumptions: Students choose between HARD and EASY SIMULTANEOUSLY. -

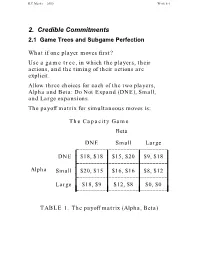

Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection

R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-1 2. Credible Commitments 2.1 Game Trees and Subgame Perfection What if one player moves first? Use a game tree, in which the players, their actions, and the timing of their actions are explicit. Allow three choices for each of the two players, Alpha and Beta: Do Not Expand (DNE), Small, and Large expansions. The payoff matrix for simultaneous moves is: The Capacity Game Beta ________________________________DNE Small Large L L L L DNE $18, $18 $15, $20 $9, $18 _L_______________________________L L L L L L L Alpha SmallL $20, $15L $16, $16L $8, $12 L L________________________________L L L L L L L Large_L_______________________________ $18, $9L $12, $8L $0, $0 L TABLE 1. The payoff matrix (Alpha, Beta) R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-2 The game tree. If Alpha preempts Beta, by making its capacity decision before Beta does, then use the game tree: Alpha L S DNE Beta Beta Beta L S DNE L S DNE L S DNE 0 12 18 8 16 20 9 15 18 0 8 9 12 16 15 18 20 18 Figure 1. Game Tree, Payoffs: Alpha’s, Beta’s Use subgame perfect Nash equilibrium, in which each player chooses the best action for itself at each node it might reach, and assumes similar behaviour on the part of the other. R.E.Marks 2000 Week 8-3 2.1.1 Backward Induction With complete information (all know what each has done), we can solve this by backward induction: 1. From the end (final payoffs), go up the tree to the first parent decision nodes.